On opposite sides of the frontline

On September 30, 2022, Russian leader Vladimir Putin delivered a speech in the Kremlin’s St. George’s Hall to mark the annexation of four Ukrainian regions. More than eight years earlier, Putin had spoken in the same hall to celebrate his first annexation — that of Crimea. However, the context and overall mood of these two events were markedly different. In contrast to the triumphant hysteria of March 2014, Russian elites in September 2022 were disoriented following the failure of the blitzkrieg invasion of Ukraine and a recent defeat by the Ukrainian army in the Kharkiv region, which forced a last-minute reduction of the annexed territories from five to four. Putin’s anti-Western rhetoric, evidently aimed at justifying the sacrifices of what had become a protracted war, also took on a new intensity.

The speech began with bitter lamentations over the collapse of the Soviet Union and accusations of neo-Nazism leveled against Ukraine, and it concluded with a reference to Ivan Ilyin, a thinker frequently cited by Putin in recent years. Ilyin, an uncompromising opponent of communism, had simultaneously supported the fascist regime in Italy and the Nazi regime in Germany. This seemingly eclectic set of talking points actually reflects a fairly consistent ideological framework of Putinism in recent years, one that underpins the bloodiest war in Europe since World War II.

This framework is most vividly expressed in a series of landmark speeches and an article authored by Putin himself, titled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” published in the lead-up to and following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Within this narrative, alongside cross-cultural references to the past — in search of “glorious years” and enemies — homophobia stands out as a cornerstone. Unlike in previous Russian regimes, where it lingered on the periphery, homophobia is now positioned at the very heart of Putinism’s ideological self-presentation. Indeed, one of the climactic moments of Putin’s speech on his largest annexation was a homophobic accusation against the West, branding it as satanic:

“Do we want, here in our country, in Russia, to have ‘Parent Number One,’ ‘Number Two,’ ‘Number Three’ instead of mom and dad — have they completely lost their minds over there? Do we want our schools, starting from the early grades, to impose perversions on our children that lead to degradation and extinction? To drill into their heads that there are supposedly other genders besides women and men, and to offer them gender reassignment surgeries? Do we want all this for our country and our children? For us, all of this is unacceptable; we have a different future, our own future… Such a complete denial of humanity, the overthrow of faith and traditional values, and the suppression of freedom take on the characteristics of a ‘reverse religion’ — outright satanism.”

These rhetorical attacks were reinforced by an escalation of institutional persecution of the queer community. Notably, on November 30, 2023, Russia’s Supreme Court issued a ruling banning and designating the “International Public LGBT Movement” as extremist. The court’s decision, framed in vague terms, labeled a broad and heterogeneous movement for LGBT rights, as well as women’s rights, and even the lifestyle of members of these communities, as extremist:

“Participants in the movement are united by the presence of a specific morality, customs, and traditions (for example, gay pride parades), a similar lifestyle (including specific choices of sexual partners), common interests and needs, and a distinctive language (the use of potential feminitive words, such as rukovoditelnitsa [female manager], direktorka [female director], avtorka [female author], psykhologinia [female psychologist]).”

In modern Russia, extremist charges entail punishment not only for participation in such organizations but also for positively portraying them or justifying their goals. Same-sex sexual relations are considered a crime in many countries, and in some — such as Iran or Saudi Arabia — they can be punishable by death. However, equating a human rights movement or mere solidarity with extremism, punishable by lengthy prison sentences, is unprecedented. Prior to this, in 2022, a 2013 law countering the “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations” among children was extended to adults. In 2023, Russia also banned transgender transitions — both the change of gender markers in documents and medical interventions related to transitioning.

The escalation of propaganda has also led to a significant worsening of attitudes toward LGBT communities among the Russian population during the years of the war, as reflected in sociological data. According to the Levada Center, over the 11 years from February 2013 to October 2024 — a period marked by Russia’s escalating aggression against Ukraine — the proportion of Russians who say they feel disgust or fear toward people with a homosexual orientation rose from 27% to 44%. As of October 2024, an additional 15% expressed irritation, 10% were wary, and only 26% reported feeling neutral, with just 1% expressing friendliness. Furthermore, 59% of Russians admitted they would reduce communication with acquaintances if they learned of their homosexual orientation, with 40% saying they would completely cut off contact.

Similarly, over the five years from April 2019 to October 2024, the share of Russians who agree that gays and lesbians in Russia should enjoy the same rights as other citizens dropped from 47% to 30%. Meanwhile, the proportion of respondents holding the opposing, discriminatory view increased from 43% to 62%.

This trend starkly contrasts with developments in Ukraine, where, amid a values-based distancing from Russia and a surge in civic solidarity due to the war, attitudes toward LGBT communities have significantly improved. According to data from the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), when asked whether LGBT residents of Ukraine should have the same rights as other citizens, more than 70% of Ukrainian respondents answered affirmatively in June 2024. This compares to 64% in 2022 and just 33% in 2016.

In recent years, high-level Ukrainian officials have also ceased using homophobic rhetoric, though they have not actively pushed for changes to legislation that remains insensitive to the rights of the queer community. For the most part, they passively observe the transformation of views within Ukrainian society. In August 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy basically supported a citizens’ petition to legalize same-sex marriage. Noting that it was impossible to amend the constitution — which defines marriage solely as a union between a man and a woman — during wartime, Zelenskyy proposed that the government develop mechanisms to protect the rights of the community through civil partnerships. However, three years later, a bill on civil partnerships has yet to be passed. Furthermore, while homophobia is no longer promoted at the highest state level, it persists — both at a societal level among broad segments of the population and through active propagation by far-right groups.

Nevertheless, the war has triggered entirely opposite trends in attitudes toward LGBT communities on either side of the frontline, and being on one side or the other means existing in a society with fundamentally different levels of homophobia.

Western roots of the homophobic tradition

Institutionalized homophobia arrived in Russia from the West as part of Peter the Great’s reforms in the early 18th century. Prior to that, Russia experienced only faint echoes of the Western European modernity that flourished at the time, which had a repressive side in the form of the Inquisition’s terror, witch hunts, and the general standardization of public life. British researcher Dan Healey, in his book “Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent,” cites accounts from foreign travelers indicating that in pre-Petrine Muscovy, not only was “sodomy” widespread, but discussions about it took place without any religious intolerance and were not considered indecent. Although the Orthodox Church imposed penances for such practices, the sanctions were no harsher than those for heterosexual adultery and were negligible compared to the ecclesiastical prescriptions and secular laws of Western Europe, where “sodomy” was often punishable by death.

During his 1697–1698 “Grand Embassy” to Western Europe, Peter I initiated reforms, including the adoption of Western legislation. The initial goal was to bring the Russian army up to Western standards. In 1706, Prince Menshikov’s “Short Military Articles,” which had limited application, included a direct borrowing from German norms prescribing the death penalty by burning for male same-sex relations. The incompatibility of this norm with the Russian culture of the time was evident, as it was never applied. By 1716, in Peter I’s “Military Statute,” the penalty was softened to corporal punishment and bore linguistic traces of borrowing from Swedish military standards. Notably, this norm was introduced not for moral reasons but out of a desire to replicate the efficiency of Western military hierarchies.

In 1835, Nicholas I extended this prohibition to Russia’s civilian male population. However, primary sources analyzed by Dan Healey suggest that Russian masculine culture maintained a lenient attitude toward homosexual practices throughout the 19th century. Even by the end of the century, the application of these criminal statutes was not widespread and primarily targeted non-consensual, violent sexual acts.

Debates about the appropriateness of the rarely enforced law on “sodomy” were ongoing on the eve of the October Revolution. Among the prominent advocates for the emancipation of homosexuality was Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, one of the leading jurists of the Russian Empire and the father of the future writer Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov. He championed liberal arguments in defense of homosexual emancipation, particularly emphasizing the principles of secularization, the right to privacy, and personal freedom.

Representatives of the gay community in Leningrad, 1920s. Archive of O.A. Khoroshilova. Source: Wikimedia

Among the Bolsheviks, there was no unified stance on the regulation of sexuality. Arguments ranged between condemning bourgeois sexual excess and the need for rational control over society’s sexual life on one hand, and the pursuit of revolutionary secularization and modernization of societal norms on the other. Additionally, the ideas of the influential German scientist and physician Magnus Hirschfeld, founder of the Institute for Sexual Research in Berlin in 1919, were popular among Russian revolutionaries. Hirschfeld advocated for the innate nature and equality of homosexuality. In 1926, at the invitation of the Soviet government, he visited Moscow and Leningrad.

Ultimately, the argument prevailed that sexual “pathologies” should be accountable to medicine rather than the judiciary. Moreover, the innovative principle of gender neutrality in Soviet legislation, which allowed both victims and perpetrators to be of any gender, made it impossible to directly inherit the gender-specific imperial legal term of “sodomy.” As a result, this norm was omitted from the Soviet Russian Criminal Code adopted in 1922 and its revised version in 1926. This approach echoed revolutionary France and stood in stark contrast to the punitive laws regarding homosexuality in most other Western countries at the time.

The article on “Homosexuality” in the first edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia in 1930 best reflected this sexual emancipation. It cited the works of Hirschfeld and Freud, attributed homosexuality to figures like Socrates, Michelangelo, and Da Vinci, and asserted that sexual perversions were “no more common in homosexuality than in heterosexuality.” Although homosexuality was still framed within the discourse of medical pathology, the article sharply condemned its legal persecution in capitalist countries:

“Abroad, and in pre-revolutionary Russia, these violations of generally accepted behavioral norms were prosecuted under special ‘morality laws.’ Not only is this legislation, aimed against a biological deviation, absurd in itself and ineffective in practice, but it also has a deeply harmful effect on the psyche of homosexuals. Even in advanced capitalist countries, the struggle to abolish these hypocritical norms is far from complete.”

However, according to art historian Olha Khoroshylova, despite the softening of policies, discriminatory practices never fully ceased during those years. By 1934, the recriminalization of “sodomy” occurred in the wake of the broader reactionary shift of Stalinism. The forced industrialization of the first Five-Year Plan, collectivization, and the strengthening of the repressive state apparatus bolstered arguments in favor of implementing stricter biopolitics.

Yet, as Dan Healey points out, this development was not without echoes of international events. At the time, homophobia became central to the confrontation between communists and Nazis in Germany. Both German social democrats and communists during the Weimar Republic advocated for ending the persecution of homosexual relationships and repealing the corresponding punitive laws in German legislation. However, when the homosexuality of Ernst Röhm, the leader of the Nazi Sturmabteilung (SA), became known, both parties sacrificed their principles and resorted to homophobia to discredit the Nazis, who were gaining political prominence. In a counterstrike, the Nazis accused the communists of “depraved homosexuality,” pointing to Dutch communist Marinus van der Lubbe, who was accused of the infamous Reichstag fire on February 27, 1933. The fire served as a pretext for banning the Communist Party, curtailing freedoms, and advancing Hitlerism. Some communists, in turn, resorted to homophobic rhetoric to distance themselves from van der Lubbe, accusing him of connections and sexual dependency on Röhm.

Thus, in the 1930s, the global communist movement’s confrontation with fascists and Nazis regressed, in part, into a competition over who could express more genuine homophobia.

This was reflected in the Soviet press as well. On May 23, 1934, an article by Maxim Gorky titled “Proletarian Humanism” was published simultaneously in Pravda and Izvestia, which, according to Gorky himself, was personally approved by Stalin. In it, homosexuality was branded as a bourgeois and fascist degeneration, and the newly introduced Soviet punitive measures were portrayed positively, specifically in contrast to Germany.

“Not dozens, but hundreds of facts testify to the destructive influence of fascism on European youth. Listing these facts is repugnant, and memory recoils from being burdened with the filth that the bourgeoisie increasingly and diligently fabricates. Nevertheless, I will note that in a country where the proletariat courageously and successfully governs, homosexuality, which corrupts the youth, is recognized as socially criminal and punishable, while in the cultured country of great philosophers, scientists, and musicians, it operates freely and without penalty. A sarcastic saying has already emerged: ‘Eliminate the homosexuals, and fascism will disappear,’” Gorky wrote, ignoring the fact that homosexuality was punished in Germany even before the Nazis came to power, and even more so after their rise.

The immediate pretext for the recriminalization of “sodomy” was the alleged uncovering of a “spy network” of homosexuals in Moscow and Leningrad, purportedly linked to German fascists. In 1933, Deputy Head of the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) Genrikh Yagoda reported to Stalin about this “network.” It was claimed that “the active pederast network, exploiting the insular nature of pederast circles for outright counterrevolutionary purposes, was politically corrupting various social strata of youth, particularly working-class youth, and attempting to infiltrate the army and navy.” According to Healey’s estimates, approximately 150 people were arrested at the time (Healey, 2001).

Following this, Stalin advocated for the reinstatement of the punitive norm, and the Central Executive Committee of the USSR, in two decrees dated December 17, 1933, and March 7, 1934, recommended that the Soviet republics reinstate the norm on “sodomy” in their criminal codes, with punishments ranging from 3 to 5 years for consensual acts and up to 8 years in cases involving violence or exploitation of a victim’s dependent status. The Ukrainian SSR was the first to respond to the December 17, 1933, decree. Later, along with other republics and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), the norm was incorporated into the RSFSR’s criminal code in 1934 as Article 154 (later Article 121).

The context of recriminalization influenced the nature of the persecution. In the 1930s, accusations of “sodomy” were closely intertwined with charges of espionage. At the same time, there was a broader societal reinterpretation of homosexuality. Rustam Alexander, in his book “Red Closet: The Hidden History of Gay Persecution in the USSR,” emphasizes that until 1933, when the Joint State Political Directorate OGPU monitored “undesirable elements,” the focus was primarily on “vagrants, beggars, prostitutes, and alcoholics” — gays were not included in this list. However, the situation changed rapidly in the 1930s, and such individuals began to be branded as “class enemies” and “corrupters of youth” (Alexander, 2023).

The conservative reaction manifested not only in recriminalization but also in the return to the pre-revolutionary, gender-specific wording of the punitive statute. Lesbian relationships continued to be considered within the purview of medicine, but now primarily through the lens of punitive psychiatry.

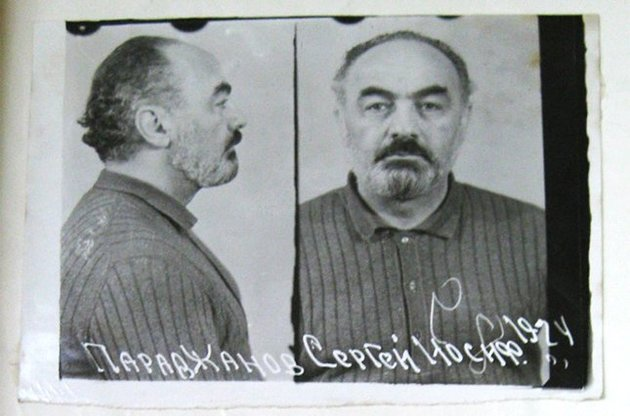

Filmmaker Sergei Paradjanov, convicted in 1974 under the “sodomy” statute. Source: ZN.UA

In the Gulag camps, homosexuals faced particularly harsh treatment, being relegated to the lowest rung of the prison hierarchy as “outcasts” (opushchennye). They endured systematic violence, humiliation, and were assigned the most degrading tasks, leading to high rates of suicides and murders. After Stalin’s death, the repressions did not cease. According to Healey, on the contrary, the party elite feared that the amnesty of millions of prisoners would bring prison homosexual practices into civilian life, prompting an even stricter homophobic policy. In 1956, Gulag head Sergei Yegorov issued a decree mandating special measures to combat “sodomy” and “lesbian love” in the camps (Alexander, 2023).

In the 1980s, with the spread of AIDS, a new vulnerability emerged: those “suspected” of homosexuality were forcibly sent to venereal disease clinics, and confirmation of homosexual acts led to imprisonment (Alexander, 2023).

The decriminalization of consensual homosexual relationships did not occur immediately after the collapse of the USSR. For two more years, hundreds of men were convicted until May 27, 1993, when the norm was repealed as part of aligning Russian legislation with European standards. Ukraine became the first post-Soviet state to decriminalize homosexual relationships, doing so in 1991.

Historical beacons of Putinism

At first glance, it may seem paradoxical that Putin laments the emergence of the USSR as much as its collapse. After all, Russian propaganda heavily emphasizes the inherited grandeur of the Soviet Union and the fetishization of the Red Army’s role in World War II. However, a closer examination of Putin’s texts and speeches, as well as those of his entourage, reveals that what primarily attracts the Russian president to the Soviet empire is its imperial character, while he harbors a deep aversion to its Soviet essence — namely, the revolutionary nature of the USSR, particularly the idea of decentralized governance through soviets.

Less than three days before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, in a speech announcing recognition and military support for the puppet quasi-state entities in eastern Ukraine, Putin expressed his hatred for the pre-Stalin Soviet period even more vehemently than for the contemporary West.

He particularly harshly criticized Lenin’s emancipatory national policy, which enabled Lenin to gain the support of a significant portion of Ukrainian elites and establish the Ukrainian SSR. “Why was it necessary to indulge, out of some lordly generosity, the endlessly growing nationalist ambitions on the outskirts of the former empire?” Putin wonders. He unequivocally assesses Lenin’s legacy: “From the perspective of the histórica fate of Russia and its peoples, Lenin’s principles of state-building were not just a mistake—they were, as they say, far worse than a mistake.” In this speech, Putin praises Stalin for his “correct” stance and policies on the national question but reproaches him for not fully breaking with Lenin’s national policy legacy, that is, for not abolishing the formal equality of Soviet republics.

The main threat to Ukraine, which Putin called a state artificially created by Lenin, was framed in those dramatic days before the full-scale invasion as a promise to carry out “decommunization” to its conclusion. For the Russian president, this means the restoration of the empire, while for Ukrainian elites, it signifies a rejection of its legacy. “You want decommunization? Well, that suits us just fine. But there’s no need, as they say, to stop halfway. We are ready to show you what true decommunization means for Ukraine.”

Putin’s aversion to Marxist principles of internationalism and emancipation is also evident in his article published six months before the invasion, titled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians”:

“The Bolsheviks treated the Russian people as inexhaustible material for social experiments. They dreamed of a world revolution that, in their view, would abolish nation-states altogether. That’s why they arbitrarily carved up borders and handed out generous territorial ‘gifts.’ Ultimately, the exact motives guiding the Bolshevik leaders as they tore the country apart no longer matter. One can argue about the details, the rationale behind certain decisions. One thing is clear: Russia was effectively robbed.”

Similarly, Putin accuses the communists of the Perestroika era of returning to Leninist principles and indulging nationalists: “The collapse of historical Russia under the name of the USSR is on their conscience.” “Historical Russia” is Putin’s euphemism for the empire. It is for the “crime” against this “historical Russia” that the current Russian leader blames both the Lenin-era communists and those of Gorbachev’s time. According to him, Russia paid for these “crimes” with its demographics. The issue of the lost population of “historical Russia” due to what he calls the two catastrophes of the 20th century — the emergence and dissolution of the USSR — is one of his favorite talking points. In 2021, he claimed that without these catastrophes, Russia would have a population of 500 million, adding that the artificial divide between Russians and Ukrainians has reduced the Russian nation by millions. This conservative obsession with not only territorial but also demographic grandeur fuels a conservative biopolitics.

Meanwhile, Putin’s elites speak of the pre-revolutionary period of Russia with nothing but reverence, frequently invoking this legacy when interpreting the motives behind the Russian-Ukrainian war. For instance, as early as March 2014, Putin justified the annexation of Crimea by the need to reclaim the imperial “symbols of Russian military glory and unprecedented valor” that emerged from the empire’s victory over the Crimean Khanate in 1783. In September 2022, he explained the necessity of annexing other Ukrainian regions as a desire to reclaim territories already conquered by imperial generals Suvorov, Rumyantsev, and Ushakov. In December 2022, Putin cited one of the main achievements of the invasion of Ukraine as the transformation of the Sea of Azov into an internal Russian sea, a goal he claimed Peter I had fought for.

From Putin’s words, it becomes clear that, on a conceptual level, he is pursuing the objectives of imperial monarchs and generals rather than seeking to restore the USSR, as Western media often suggest. Finally, Vladimir Medinsky, head of the negotiating delegation with Ukraine and one of the chief ideologues of Putinism, compared the Russian-Ukrainian war to the Great Northern War with Sweden, waged by Peter I, which marked the emergence of Russia as an empire.

Thus, the simplified compass of Putin’s attitude toward Russia’s historical journey is remarkably clear: the building of the empire under Peter I — very good; the October Revolution — very bad; Stalinism and the subsequent development of the USSR — relatively good; Perestroika, the collapse of the USSR, and the democratization of the 1990s — very bad. This aligns with the Russian state apparatus’s approach to homosexuality: the introduction of punitive norms under Peter I, decriminalization under Lenin, recriminalization under Stalin, and decriminalization again amid the democratization of the 1990s. Of course, throughout this period, homosexuality was far from the centerpiece of ideology. However, attitudes toward it mirrored broader trends—either the strengthening of centralized power and unifying biopolitics or, conversely, the rise of pluralism and emancipation. The latter, within the framework of conservative Putinism, is perceived solely as an undermining of the empire.

This historical orientation naturally aligns Putin with Ivan Ilyin, a monarchist in the Russian context and a theorist of fascism in the Western one. What unites Putin with National Socialism and fascism is a shared aversion to the emancipatory principles of communism and liberalism, whether contemporary or from a century ago. Even when referencing the crucial victory in World War II, Putinist narratives typically portray the Nazis as an abstract, foreign invading army from the West, akin to Napoleon’s forces. At the same time, in their details, Putin’s officials focus far more on the imagined “neo-Nazism” in Ukraine than on the classical Nazism of the Third Reich.

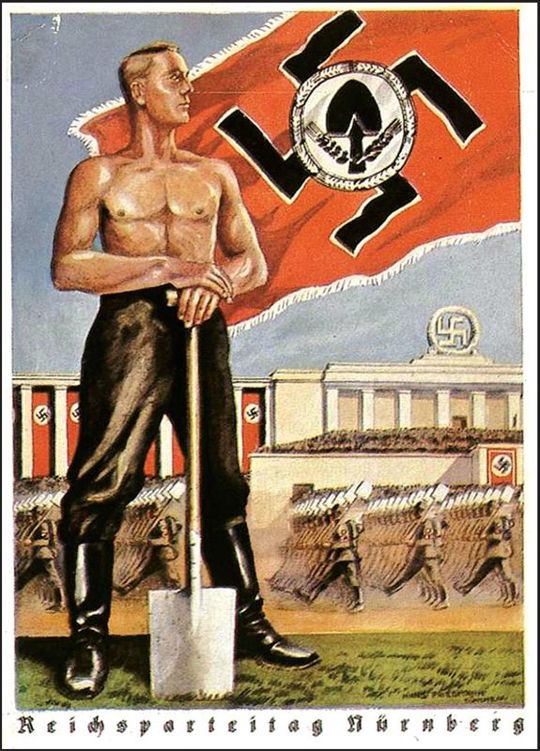

Image of an ideal man on a Nazi propaganda poster, 1938. Source: Erenow

In Germany, the criminalization of homosexual practices among men predated 1933, but Paragraph 175 of the Criminal Code was further tightened by the Nazis: even kisses and touches were now punishable. In 1933, the Institute for Sexual Research, founded by Magnus Hirschfeld, was demonstratively shut down, with the scientist’s Jewish heritage playing a significant role in this decision. Between 1935 and 1945, the Nazi regime convicted around 50,000 men under this paragraph, with 5,000 to 15,000 of them sent to concentration camps; some were subjected to castration. Homosexual men in the camps were identified by pink triangle badges. As in the USSR, the law did not apply to women, though they were persecuted under other criminal statutes.

Researchers Günter Grau and Claudia Schoppmann, in their book Hidden Holocaust? Gay and Lesbian Persecution in Germany, 1933–1945, compiled and analyzed over 100 laws, decrees, protocols, letters, and speeches that shed light on the Nazi regime’s approach to gender issues (Grau & Schoppmann, 1995). They note that even those who were not convicted underwent various forms of “reeducation” or were forced to deny their sexuality, abandon their usual sexual practices, or enter into sham marriages. In any case, they remained under close surveillance by the system. Political fears about solidarity and the potential organization of underground homosexual networks also played a role within the framework of total control.

Based on the analysis of Nazi regime documents regulating gender issues, Professor Sam Garkawe of Southern Cross University concluded that, unlike Jews, the Nazis never intended to exterminate all homosexuals but rather sought to eliminate homosexual acts or the “homosexual type” of person. Homosexual contacts threatened the ideal of the nuclear family, which underpinned Nazi society. This “family” was entirely oriented toward procreation and population growth. In 1936, the Germans established the “Reich Central Office for Combating Homosexuality and Abortion,” as both phenomena were considered direct threats to demographic goals. Women were deemed more “curable” than men since, despite lesbianism, they could still bear children. One method of “reeducation” involved forcing women into brothels to work as prostitutes.

Putin’s homophobia stylistically resembles the Nazi biopolitics of hegemonic masculinity (in Raewyn Connell’s terms), which aimed to enhance productivity and prepare the population for military expansion. Nazi ideology glorified militarized, heteronormative masculinity embodied in the image of the “Aryan warrior”: a strong, disciplined man who protects the nation and contributes to its demographic growth, while marginalizing homosexual masculinity.

In modern Russia (since the 2000s, particularly the 2010s), the image of the “strong man” has been promoted — patriotic, heteronormative, militarized, and associated with traditional values and the “defense” of the Russian nation against “Western influence.” Equating advocacy for LGBT rights with extremism underscores the perception of queer culture as a hostile force, a breeding ground for political subversion, and a threat to the regime. These motives, though modernized, generally echo those of Nazism and Stalinism. At the same time, on the rhetorical level, a new motif emerges that shifts homophobia from the periphery to the very center of ideological self-presentation.

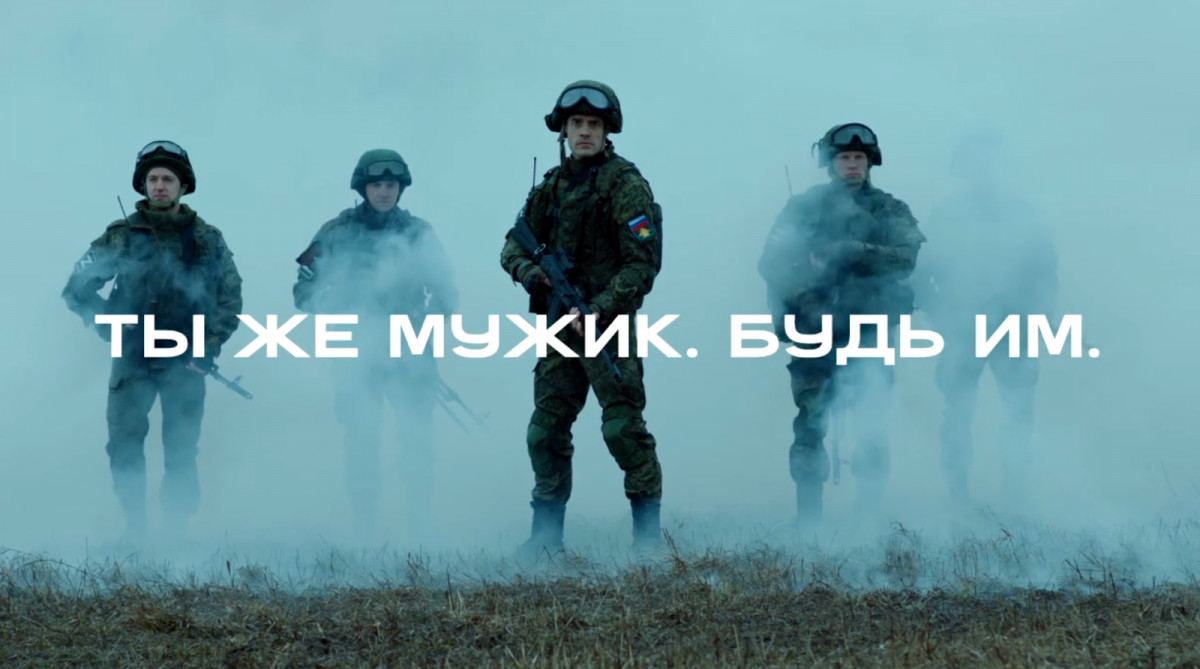

“You’re a man. Act like one.” Screenshot from a Russian army recruitment ad. The video promoted abandoning “unmanly” peaceful professions such as supermarket security guard, gym trainer, and taxi driver in favor of the “manly” profession of a soldier, 2024. Source: KP.RU: Komsomolskaya Pravda page on dzen.ru

The last bastion of moral superiority

Modern Russia distinguishes itself from both the imperial and Soviet periods by the absence of a reliable ethical argument for confronting the West.

The international actions of the Russian Empire in the 19th and early 20th centuries followed the wake of an internal ideology that can be simplified to the triad of “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality,” proposed under Nicholas I by the tsarist minister Count Sergei Uvarov. This ideology necessitated the autocrat’s care for Orthodox Christians and Slavs, while also expanding Russia’s ambitions to the territories where they resided. A telling example of implementing this ideology is Alexander Pushkin’s 1831 poem “To the Slanderers of Russia,” where the military suppression of the Polish uprising of 1830–1831 is described as a “domestic, ancient dispute among Slavs themselves.” According to Karl Fickelmon, the poem was personally approved by the Russian emperor. Russia’s mobilization in July 1914 following the Sarajevo assassination in support of the Slavic and Orthodox Serbia became one of the decisive triggers for World War I, which the Russian Empire did not survive.

The Bolshevik ideology of the USSR had a universal character. Oppressed proletarians could exist in any corner of the world, so the influence of the most powerful socialist state, including through military actions, faced no geographical limitations. To justify violence, Moscow’s propaganda at the time employed clichés recognizable worldwide.

The military suppression of the Hungarian anti-Soviet revolution in the fall of 1956 was characterized by the Great Soviet Encyclopedia with theses familiar to all socialist communities: “an armed uprising against the people’s democratic order, prepared by internal reactionary forces with the support of international imperialism, aimed at liquidating the socialist achievements of the Hungarian people and restoring the dominance of capitalists in the country, who, along with the petty-bourgeois elements that joined them, formed the class base of the counterrevolution.”

In a similar vein, on August 21, 1968, the main Soviet state news agency TASS justified the start of the military suppression of the Prague Spring as a “threat to the achievements of socialism in Czechoslovakia and to the security of the socialist community countries.” Although the liberalization was implemented by Czechoslovakia’s official socialist authorities themselves, the invasion, according to TASS, occurred at the request of “party and state leaders of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic” to counter “counterrevolutionary forces that had conspired with external forces hostile to socialism.” In this way, the USSR purportedly fulfilled its international obligations in support of socialism, including in the Afghan War.

Modern Russia lacks both the morally grounded argument for the superiority of a socialist system, as was the case during the Cold War, and a fully developed religious argument in favor of Orthodoxy or the international pan-Slavist movement. Russia operates under capitalism, like the West, and secular authority is formally separated from the church, as in Western states. Overall, Western culture predominates, albeit in a somewhat modified form. To fill this ideological void, Russian ideologues eclectically appeal to concepts like the “Russian world,” the “correct traditional Europe,” or, as outlined in the officially adopted 2023 foreign policy concept, position Russia as a “distinct state-civilization.” Yet all these concepts lack substantive content. What constitutes the moral essence of this Russianness, correctness, or distinctiveness that allows Russia to threaten the world with nuclear annihilation?

In the aforementioned 2022 speech regarding the annexation of Ukrainian territories, Putin justified the need for confrontation as follows:

“The battlefield to which fate and history have called us is a battlefield for our people, for the great historical Russia, for future generations, for our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. We must protect them from enslavement, from monstrous experiments aimed at crippling their consciousness and soul.”

But what are these monstrous experiments that supposedly threaten to cripple the souls of future generations? In reality, the domestic Russian audience instinctively understands what is meant. Homophobia emerges as a saving argument — effectively the primary one on which the authorities rely to morally justify the war.

Russian propaganda is generally inclined to mock and discredit not only the human rights movement in support of LGBT communities but also other major contemporary ethical trends in Western societies: anti-racism, environmentalism, and feminism. However, in no other sphere can it achieve the escalatory extremism necessary to justify war. Racist policies would quickly spill over to ethnic minorities within Russia, particularly those from the North Caucasus, undermining internal stability. Moreover, racism would alienate partners in the Global South. While the stereotyping of women’s roles flourishes in modern Russia, implementing anti-feminist policies has its limits. Russian women gained fundamental rights, such as equal access to education, voting rights, and abortion rights, over a century ago. Radically rolling back these rights would provoke significant resistance. Even in the realm of ecology, despite the discrediting of global environmental movements or the dismissal of the fight against global warming, it is impossible to completely detach from the need to ensure a minimal level of environmental order for Russia’s own population.

Homophobia, however, is readily understood across all societal strata. It resonates with the older Soviet generation, which lived through times when homosexual acts were criminalized or “treated” within punitive psychiatry, as well as with a significant portion of the youth, among whom dominant masculine behavioral models remain popular. It is also comprehensible to Putin’s administrative elites, who come from security agencies, criminalized circles, or the deeply patriarchal environments of Muslim North Caucasian republics. In all these spheres, rigid hierarchies of masculinity prevail. Furthermore, without losing allies among key partners in the Global South who are insensitive to human rights advocacy, homophobic Russia also garners support among Western conservatives waging their own war against the “woke culture” they despise.

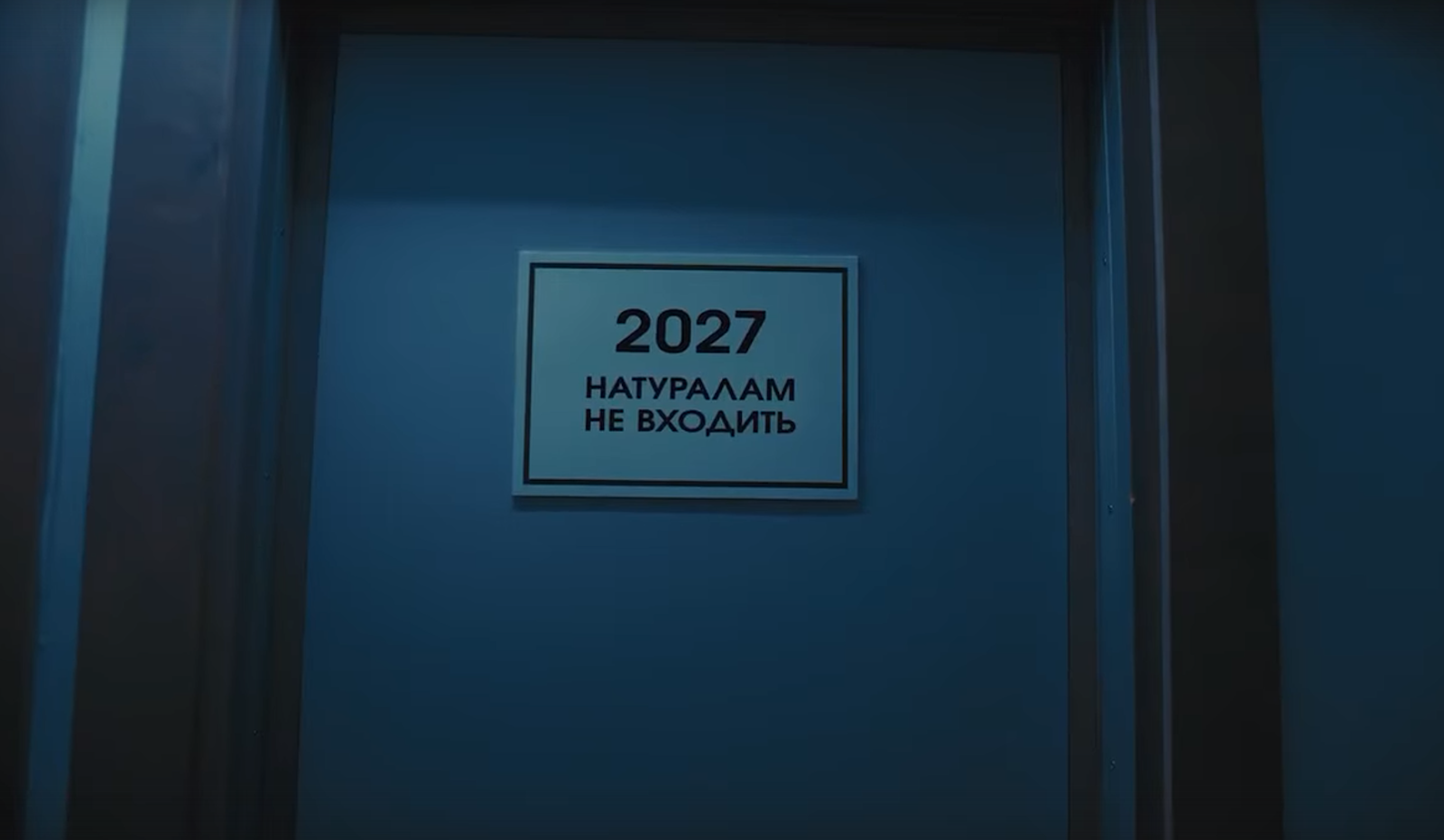

“2027: No Entry for Straights.” Screenshot from a Russian propaganda video, 2024

Following the path of least resistance, homophobia consistently appears in the rhetoric of Russian officials and propagandists to justify an existential confrontation with the West. Similarly, a recurring theme in the propaganda videos for the Russian presidential election in March 2024 was the depiction of an undesirable “gay” future for Russia, which would supposedly materialize if a Russian citizen failed to vote or did not vote for Putin. In this imagined future, queer culture is hyperbolically portrayed as dominating in a repressive manner. In one such video, the protagonist skips the election and finds himself sequentially transported to rooms from the future, each depicting escalating images of evil. In the 2025 room, he encounters a queer party. In the 2026 room, he witnesses a mother harshly scolding her child for not using feminitive word forms, and in the corridor, he comes across a gender-neutral bathroom where he meets a transgender woman. By 2027, entry is outright banned for “straights,” which can be interpreted as repression against them.

In these videos, as well as in some speeches by Russian officials, the portrayal of the West’s supposed domination by queer culture is exaggerated to a carnival-like degree. However, the extent of this ironic exaggeration remains unclear to the audience. At the same time, the audience picks up the signal from the authorities that they welcome the conformist reproduction of the homophobic argument among the population. The humorous hyperbole serves as an alibi, shielding against the realization of the absurdity of using such an argument. Yet the extremist law punishing solidarity with the LGBT community is entirely serious, as evidenced by over 100 convictions already handed down.

In this meta-ironic manner, Sergey Karaganov, a Kremlin-affiliated “foreign policy expert” and advocate for escalation, publicly proposed at the 2024 St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, in Putin’s presence, launching a nuclear strike on Europe. He justified this by invoking the need to restore homophobic divine will, taking the moral high ground to its extreme:

“If we do not move more decisively up the ladder of escalation, will we not neglect the gifts of the Almighty? After all, the Almighty once showed us the way when He destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah with a rain of fire for their debauchery and licentiousness. For many years afterward, humanity remembered this and behaved cautiously, but now it has forgotten Sodom and Gomorrah. So perhaps we should recall that rain and try to bring humanity — or that part of humanity that has lost faith in God and lost its reason — back to its senses?”

Such a public proposal to use nuclear weapons in Putin’s presence sends an escalatory signal in itself. This vividly demonstrates that homophobia has taken center stage in Russia’s ideological presentation, not for its positive meaning to the regime, but as a moral argument for existential confrontation and escalation with the West. In the absence of other compelling arguments, homophobia emerges as a default. The ideologeme of homophobia becomes a life preserver for Putin’s elites amid ethical disarray and a broader crisis of meaning-making.

This publication was produced with support from n-ost and funded by the Foundation Remembrance, Responsibility and Future (EVZ) and the Federal Ministry of Finance (BMF) as part of the Education Agenda on NS-Injustice

Healey, D. (2001). Homosexual desire in Revolutionary Russia: The regulation of sexual and gender dissent. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Alexander, R. (2023). Red closet: The hidden history of gay oppression in the USSR. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Garkawe, S. (1997). [Review of the book Hidden Holocaust? Gay and lesbian persecution in Germany 1933–1945, edited by G. Grau, trans. P. Camiller]. Melbourne University Law Review, 21(2), 738–742.

Grau, G., & Shoppmann, C. (Eds.). (1995). The Hidden Holocaust?: Gay and Lesbian Persecution in Germany 1933–45 (1st ed., trans. P. Camiller, illustrated with facsimiles and portraits, pp. xxviii, 307). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315073880.