In this decade, we’ve seen the revolution of modern warfare, and especially the usage of drones. First prelude was 5 years ago: during the Second Karabakh war, Azerbaijan successfully used Turkish Bayraktar and Israeli Harop drones to penetrate Armenian air defence systems. The war in Ukraine has only solidified the significance and impact of drones in warfare, and led to an increase in their capabilities and purpose. There have been countless examples of that, among the latest is Ukrainian operation “Spider web”. What was brilliant is not just smuggling drones to Russia, but the usage of fiber optic drones to avoid standard anti-drone jammers. Unfortunately, with the massive help of Islamist regime of Iran, Russians are not falling behind with Shahed drones and their ability to bypass air defences.

Drones made change not just in modern warfare. The necessity to repair them and extend their life cycle raised hundreds of grassroots volunteers and created a community in Ukraine. Here are just few examples: “Halabuda”, a group of Mariupol volunteers residing in Cherkasy; “Weekend drone”, created by Odesa civil organisation “Crimean Tatars of Odesa”; and individuals dedicating their time to this. Aside from drones, there are also communities and volunteers repairing Starlink terminals.

Why have I started this article with a story about drones? Because the ability to repair electronic devices – therefore extending their lifecycle and saving money on buying a new item when it’s unnecessary – is just one of the very many reasons why we should have the same availability for our daily gadgets such as laptops, smartphones, smart watches and Internet of Things devices, and other consumer products.

Aims and goals of right to repair

With the technology advancement, several manufacturers have begun implementing lockout mechanisms in order to centralise the maintenance and repairs. Back in 1985 Nintendo Ltd, a famous Japanese game company, released the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) gaming console. Despite the 1983 crash of the video games industry known as Atari shock, NES has been a massive success for the company and stimulated the recovery of industry to the sales levels of pre-1983. According to American magazine Compute!, in just one year Nintendo was able to sell more NES consoles than Commodore 64 over five years.

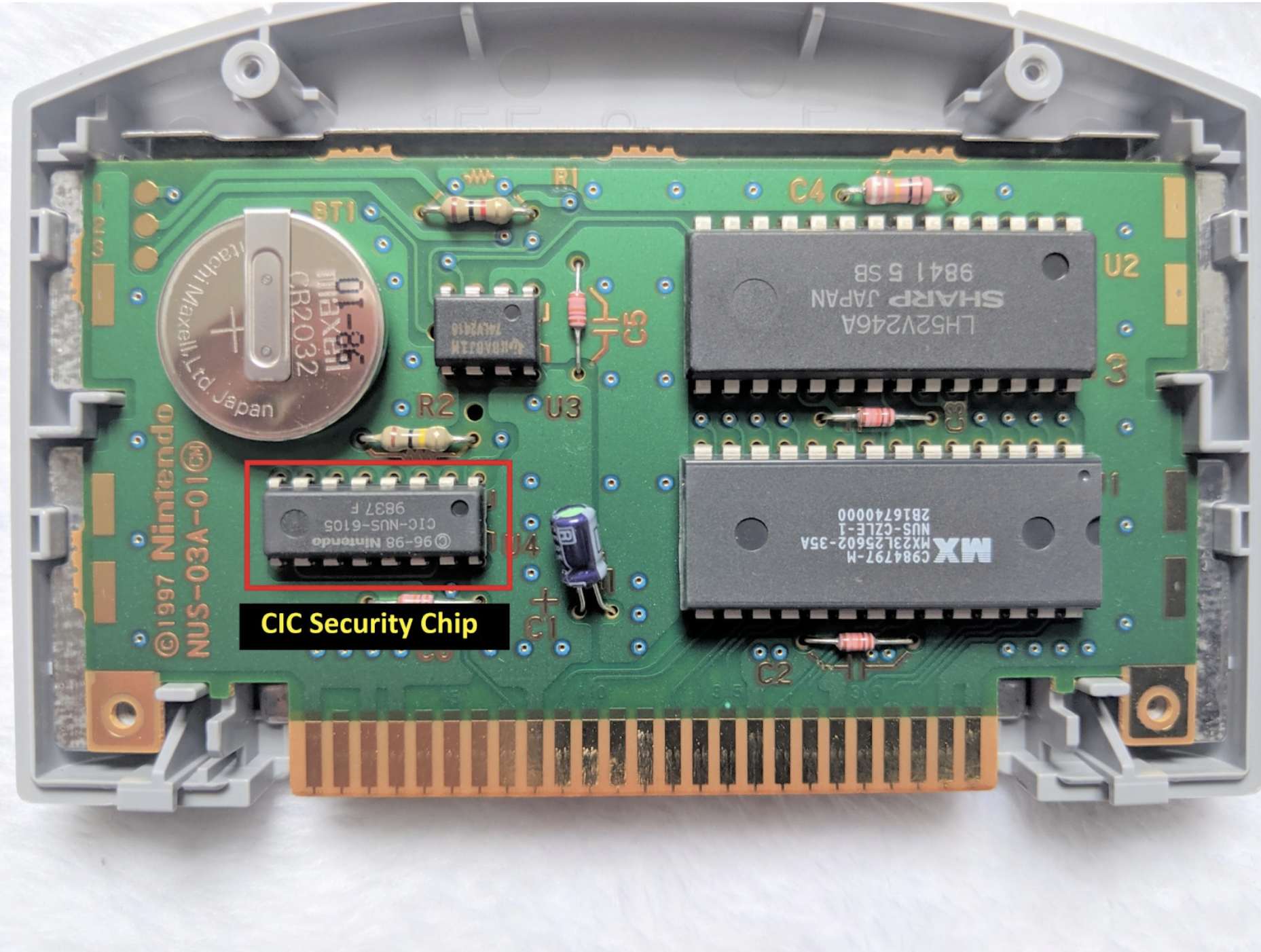

However, it also presented an opportunity for Nintendo to establish complete control over which games can run on a NES console to prevent the situation that arose during Atari shock when the unlicensed cartridges with poor quality games flooded the market. As a result, Nintendo created a Checking Integrated Circuit (CIC) chip that became a key element of a 10NES lockout system. Its aim was to verify the game authenticity, licensing and region, therefore preventing usage of unauthorised and unapproved gaming cartridges with the NES console. This – with the success of NES in general – has provided Nintendo an absolute control over the gaming market for their console in two ways.

Photo of a disassembled NES cartridge. CIC Security Chip is highlighted

Firstly, it gave them an ultimate bargaining chip in negotiations with game studios over manufacturing of cartridges and sales profits. In the book Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children[1] David Sheff described that Nintendo demanded: end-to-end control over cartridge manufacturing and 10,000 cartridges as the least amount that can be ordered; full absolution of any risks; hefty royalty from each sold game ($5 per cartridge); and insisted on games’ exclusivity and limit of up to 5 games per year. Game studios were unhappy with such terms but, being attracted with NES popularity and profits, fell in line – even if it meant they were at Nintendo’s mercy.

Secondly, it gave them a final say in the content for games to be released on NES. Specifically, due to Nintendo positioning itself as a family-friendly company, the company demanded games to be free of adult content, alcohol, blood and everything Nintendo didn’t consider suitable. Nintendo’s president Hiroshi Yamauchi admitted himself that censoring games was clearly one of the goals behind the 10NES system.

As a result, several game studios attempted legal and illegal means to circumvent the CIC chip protection, and Atari Games managed to succeed.

In 1987, Tengen (a substudio within Atari dedicated to creating games for NES consoles) and Nintendo negotiated terms for releasing games on NES and signed a licence agreement. It didn’t stop Atari and Nintendo battling in courts one year later over rights for Tetris, which Nintendo won; in response Tengen developers managed to reverse engineer the CIC chip and bypass the 10NES system restrictions. Nintendo, known for being very jealous regarding copyright and intellectual property rules, sued Tengen once again over copyright infringement – and once again successfully. First they were granted the right to go against any retailer selling Tengen cartridges, then prevailed with banning them permanently.

This is just one of the examples that demonstrates how a consumer doesn’t fully own the purchased product due to the monopoly of a manufacturer on hardware or software, and therefore is dependent on whatever restrictions the manufacturer imposes.

Designed to solve this problem, right to repair is a legal right to upgrade, modify or repair consumer products, either by owners and/or independent third-party repair shops. The goals that right to repair movements aim to achieve (e.g Right to Repair Europe) are to:

1. Make the information about repairable consumer products public for everyone. That includes the gadgets schematics, hardware components, and ideally software updates.

2. Provide universal and affordable access to the necessary tools and enforce usage of interchangeable components in the devices to improve the interoperability. While making the information public is crucial, without being able to buy spare parts and necessary tools to replace those parts such information is of little use. On top of that, even if it’s accessible, it should not cost more than buying a new device. Right to repair should eliminate legal barriers for end users to modify the devices they own as they see fit.

3. Extend the device lifecycle and support, ideally even beyond its official dates. It isn’t right to throw away your laptop or smartphone due to expiration of software updates support, or because hardware isn’t sufficient enough for some apps (e.g low amount of RAM or not enough space on a disk drive). Recent examples of Microsoft telling consumers who cannot upgrade to Windows 11 from Windows 10 due to hardware requirements “buy new PC” and a response campaign “End of 10” demonstrate the importance of extending hardware lifecycle. It should be possible to continue using your device by upgrading RAM and hard drive and installing an operating system that still provides updates regardless of the hardware.

The first steps for right to repair reforms began in the early 1990s targeting the automotive industry. In 1990, several amendments to the Clean Air Act in the USA were passed that made the requirement from the automakers to introduce a standardized car interface allowing it to monitor its emissions, which resulted in creation of an OBD-II port that is still used in cars up to present day. But the main battle began in 2001 with the introduction of Motor Vehicle Owners' Right to Repair Act at federal level – which was supposed to require automobile manufacturers to share the same information as they do with dealers to independent car repair shops to break up the monopoly on repairs. Although the bill didn’t advance in the Senate due to extensive lobbying by automakers, later on various American states eventually managed to advance them at the local level. The landmark law was passed in Massachusetts in 2012 where at the referendum 86% voted to support the legislation, and it caused a domino effect: automakers agreed to provide repair data for independent shops not just in Massachusetts, but in other states as well. Three years later, two more major achievements helped gaining the momentum for the future right to repair legislations. First, the Copyright Office of the United States ruled exemptions for repairing tractors, cars and tablets; and second, the US Senate unanimously passed the bill to make the cell phone unlocking legal.

President Barack Obama signs S. 517, Unlocking Consumer Choice and Wireless Competition Act, in the Oval Office, Aug. 1, 2014. Official White House Photo by Pete Souza

While one couldn’t imagine that right to repair would be a key element of the automotive industry 20-30 years ago, nowadays it is absolutely common to have independent repair shops – which save a lot of money rather than going to the official dealer shop. The same should be with consumer electronics.

Yet it hasn’t been easy, and there’s still a long way to go.

How big tech takes away the ownership of your products, and right to repair helps taking it back

Apple has been one of the biggest right to repair opponents – which is fascinating because originally Apple I and Apple II computers were the opposite: computers with accessible circuitry designs. Apple I designs were even given away for free by Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple and hardware & software engineer. Apple II also had eight expansion slots for additional devices & cards, providing more options for modifications.

But another Apple co-founder Steve Jobs had a different approach. He has always pushed for an ecosystem where users have to use only either Apple-designed or, later on, Apple-approved software and hardware, having it tightly linked. In the case of Apple II’s expansion slots, he insisted only two would be enough instead of eight, but eventually conceded; he wasn’t in such mood with Macintosh, and especially after his return to Apple in 1997. Over his life, Jobs vehemently denied any attempts to open up the Apple ecosystem, and it was on display multiple times. Famous cases were his opposition to creating Windows version of iTunes software and therefore forcing the iPod consumers to buy Mac for uploading songs to their player, and his reaction to Android OS and its openness which was the antithesis of Apple’s iOS.

Apple didn’t limit its maniacal control with software: back in 2009, Apple introduced custom tamper-resistant Pentalobe screws for Macbook Pro laptops to prevent replacing laptop batteries (later those screws were used for iPhone 4). These screws are still used in Apple products; although nowadays it’s easier to purchase fitting screwdrivers, back then they were inaccessible.

Different types of screws used in Apple devices

Even after Jobs’ death, Apple kept its “walled garden” – a definition describing Apple’s ecosystem – as tight as possible, especially when it comes to hardware. For several years, Apple tirelessly lobbied against the ability to repair its devices independently. Retina Macbook Pro models released in 2012 were the first ones where RAM memory was soldered to the board, and the same happened with storage drives later. Tamper-proofing of the battery went further: on top of using Pentalobe screws, now it was glued to the bottom with an adhesive. Further on, in 2016 Apple added the hardware check for a home button component to iPhone 6 which causes device to brick if the repair was carried out by a third-party. There are many other similar cases which have carried on over the years; recent is Face ID not working after screen replacement in iPhone 13 due to hardware check by iOS. It was eventually fixed with a software update but only after the uproar that was covered in the media.

As a result, Apple’s monopoly on repair services ramped up repair prices uncontrollably, even to a point when cost of repairs were barely cheaper than buying a new laptop. In 2021, Wall Street Journal released a video comparing repair prices for two damaged Macbooks (Pro 2017 and Air 2020) and its availability in two independent repair shops and Apple customer service. The results were staggering in two aspects:

– Apple requested $800+ per each laptop to repair, while Apple-authorised repair shop sets even higher costs. At the same time, an independent repair shop owned by Louis Rossmann, electronics engineer and long-time outspoken activist and supporter of right to repair, evaluates the repair of Macbook Pro at $325. Another repair shop offers $500;

– However, both independent repair shops could not repair Macbook Air because they didn’t have access to the schematics and necessary components. And even with Macbook Pro, those schematics have been received at huge risk due to NDAs (non-disclosure agreements).

No wonder every time local or national governments attempted to push right to repair laws – which would significantly reduce Apple’s profits on repairs – the company vehemently lobbied against them and, if it failed, aimed to water down those laws on the grounds of “right to repair undermines security, safety and privacy of devices”. This happened in 2022 when New York governor Kathy Hochul refused to veto the right to repair law but instead signed a watered-down version of it after extensive lobbying from the big tech. Despite this being the landmark as the first state to sign the right to repair law regarding consumer electronics, it was rightly criticised by campaigners.

Nevertheless, thanks to the fact that the New York right to repair law – even a weakened version of it – was signed, the right to repair movement has managed to gain support from all political sides in the United States and launched a domino effect. Apple continues to lobby against the right to repair tirelessly while pretending to support it – and sometimes even contradicting itself (supporting in California but opposing in Oregon). While other big tech companies have also been caught in lobbying against it, some of them eventually began changing their minds, as happened with Microsoft and Google. At this moment, all states in the USA have introduced corresponding bills, and in 6 states (New York, California, Minnesota, Oregon, Maine, and Colorado) they were signed into law.

But the biggest achievement so far was made in the EU.

In spite of effortless lobbying and some watered down provisions, in 2024 the European parliament passed the most comprehensive law regarding right to repair which required:

– mandatory minimum of 2 year warranty on repairs of household products and even after expiry of official warranty period;

– providing additional year of warranty period after device is repaired;

– provision of spare parts and tools and barring to provide software checks that would obstruct repairs;

– making information about repairs easily accessible.

These measures were strengthened with new rules enacted since June 20th 2025, now requiring:

– mandatory software and security updates for devices for at least 5 years since a device was released;

– supplication of spare parts and tools for 7 years since device is stopped being sold in EU;

– usage of more durable batteries;

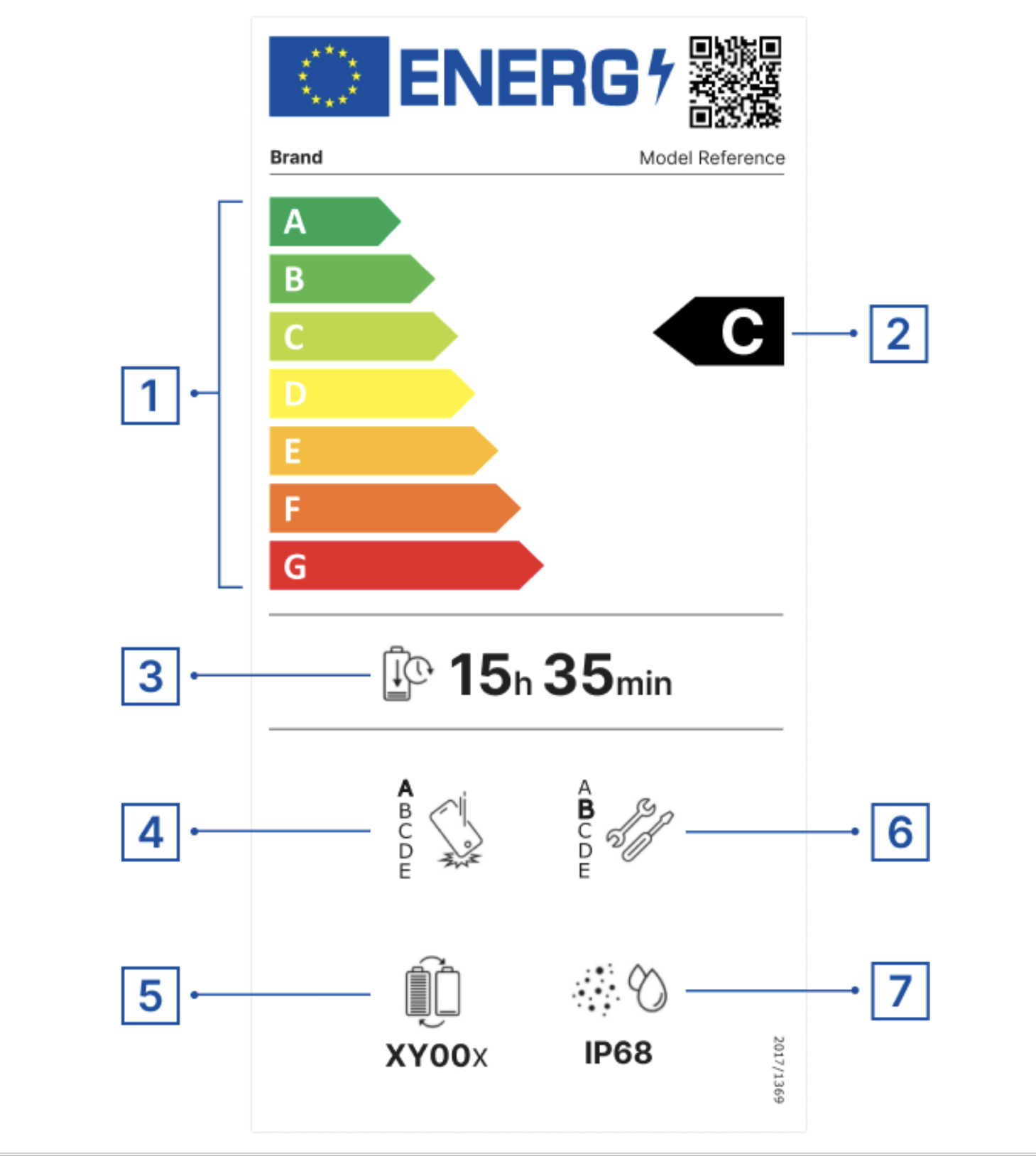

– mandatory “energy efficiency labels” for smartphones and tablets.

Smartphone and tablet label sample proposed by EU. It describes device’s characteristics such as energy efficiency, repairability, battery endurance and life cycle, and protection against dust and liquids

Across other countries and continents, the right to repair legislations are also gaining momentum. Canada and Australia have passed corresponding bills, while New Zealand, Brazil and Colombia have introduced them. In African countries – specifically Uganda and South Africa – the community support for repair culture is also getting popular.

While some of the laws regulating right to repair, both enacted and introduced, may have flaws, this is an enormous progress over the past few years – yet we should keep pushing for more changes, and closing loopholes in existing legislations.

Impact and benefits of Right to Repair

So, what does improved repairability of electronic devices achieve? And why do we need it?

First reason is very basic and sensible: it reduces the cost of repairs for consumers. People rarely want to part with their electronics and would prefer to have them repaired than buy a new product. However, due to manufacturers’ barriers, lack of clear information and inflated cost, it drives consumers away from repairing towards buying a new product – even if it’s more expensive. A study from 2018 commissioned by the European Commission (EC) and focused on products such as vacuum cleaners, televisions, dishwashers, smartphones and clothes shows that 64% of consumers would try to repair their products. Multiple surveys and researches of consumer behavior by EU Horizon’s PROMPT project also confirm that consumers’ decisions to replace the product rather than repair is caused by lack of repair shops and high prices.

Second reason is environmental. By making the electronic products sustainable and interoperable, right to repair makes a positive impact on health and environment. E-waste is making a significant contribution to the carbon emissions, and its amount is rising every year. Research from 2022 shows the estimates of up to 6% to global emissions sourced by technology, with the global supply chain of electronics being among top-8 sectors accounting for more than 50% of global carbon footprint. In addition, e-waste poisons the environment, causing major health risks for waste management labourers and especially children due to toxic materials used in components for manufacturing and production of electronic devices. Food supply is also being affected by e-waste’s catastrophic effects. Agbogbloshie hosts not just one of the Ghana’s largest food markets, but also one the world’s largest e-waste dumps – and according to a study by two environmental groups, a free-range chicken egg hatched in Agbogbloshie exceeded European Food Safety Authority limits on chlorinated dioxins, which cause cancer, by 220 times.

Cows grazing at e-waste site in Agbogbloshie, Ghana

With the UN-led E-Waste Monitor research group predicting a 32% rise in e-waste between 2022 and 2030, it is clear that reducing e-waste is absolutely imperative, and right to repair is a key element in fighting climate change and improving global health. A study by the European Environmental Bureau from 2019 looking at the impact of repairability of TVs, smartphones, laptops and washing machines concluded that by extending the life cycle of these four groups of products by 5 years could save the annual amount of emissions comparable to taking over 5 million cars off the road each year. Even extending the life cycle of products by 1 year would save the amount of emissions comparable to 2 million cars.

Finally, right to repair benefits the overall economy by establishing repair skill-sharing communities and stimulating the circular economy. It provides jobs (European Parliament’s New Circular Economy Action Plan 2021 counted 700,000 new jobs in the EU by 2030) and makes an overall positive impact in the labour market, as evaluated in a 2020 OECD report. Also, by extending the life cycle of products and especially electronic devices, it will help reduce the Western countries’ dependency on rare earth materials used for electronics manufacturing. And it’s not just extraction: processing of minerals is almost exclusively done in China.

Across the world, several community organisations were created where people set up events in which they attempt to fix broken products, and others can bring them up. Repair Cafe and Restart Project are just a few examples – and those are worldwide names; there are also hackerspaces and domestic community groups. Yet it’s not also just about fixing items, but also sharing such useful skills with each other is extremely beneficial and important. One of the stories that really reflects this point is about the UK's only braille typewriter engineer whose work to fix typing machines for blind people is so crucial that schools and support services admit they’ll be stuck without him as he’s getting closer to retirement.

I believe the achievements of right to repair campaigners serve as an impeccable example of how we can fight against big tech. Pushing for such reforms on the basis of basic needs for citizens, climate change, reduction in expenses, and respect for the consumer rights will be appealing for a regular consumer, especially for lower income groups of people who don’t want to spend their money on products when it’s not necessary.

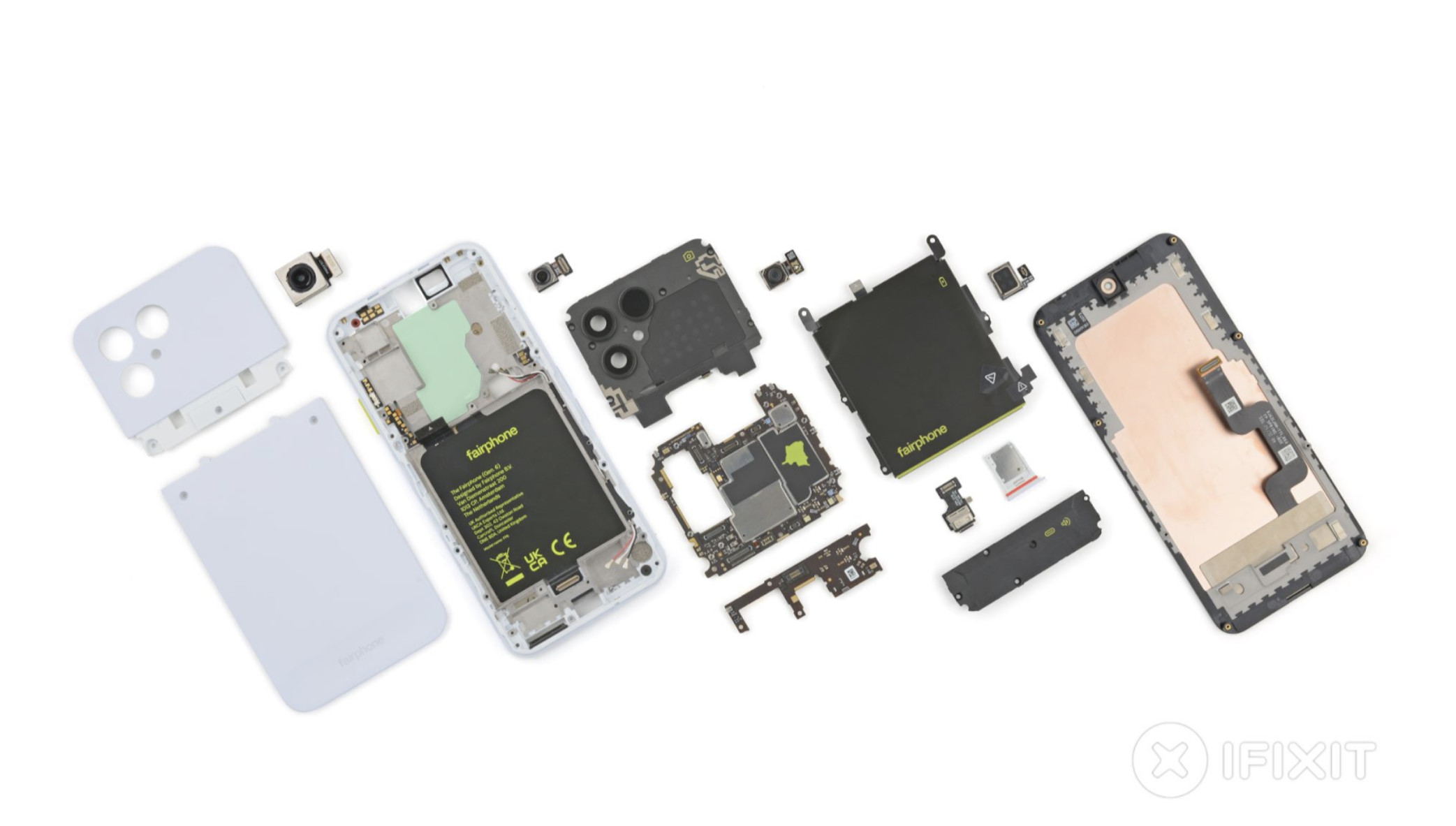

Fortunately, there are shifts in creating modular consumer devices that are close to 100% e-waste neutral. Among smartphones, such company is Fairphone; they recently released a Gen 6 smartphone with an impressive level of repairability. Framework is a similar company among laptops. Other vendors have also started making their devices more modular than before. There are also numerous websites that sell parts and tools to modify and repair electronic devices – iFixit being the most prominent one. In addition, they provide easy guides and forum topics which describe step-by-step replacement procedures for electronic devices, but also kitchen appliances, cars and even medical devices.

Disassembled Fairphone Gen 6. iFixit gave it a 10 out of 10 in repairability score

Ukraine’s chance of a lifetime

Unfortunately, even though Ukraine is on the path of joining the European Union and will eventually have to adopt the right to repair law, the Ukrainian government hasn’t taken any initiative in drafting a national legislation on right to repair (like France), and the corresponding petition received only 42 signatures. I believe it will result in a missed opportunity.

Many volunteers who work on repairing drones, Starlink terminals and other hardware used by Armed forces of Ukraine acquired a precious set of skills that cannot be thrown away in a post-war period. It’d be short-sighted to discard those skills in a post-war period – therefore, documenting and sharing such skills by different local tech communities for the general population will be beneficial. In a way it’s already happening regarding drone and Starlink terminal repairs, but it should not fade away under any circumstances, and such knowledge might be useful to apply into repairing consumer products.

After the war eventually ends, there will be hundreds and maybe even thousands of Ukrainian volunteers, engineers, and servicemen with valuable repairing skills and knowledge on electronics, and it shouldn’t be wasted. Setting up repair shops and start-ups which focus on hardware assembly & modularity of devices will provide a boost for the economy, with small & medium businesses driving the growth.

Most importantly, the experience gained by working with electronics can lead to something bigger and more important for Ukraine than just repairing products: becoming a European hub of innovative technology & electronics manufacturing.

The EU is currently at the crossroads. With the growing threat from China and significant dependency on Chinese minerals and resources, the EU urgently needs to diversify – and Ukraine has the opportunity to step in. In May, Maryna Larina wrote a fantastic article in Commons about Ukraine’s presence of raw minerals and resources, their geopolitical importance, and how plain export & extraction will aggravate an already acute dependency on exports of resources. I wholeheartedly agree with this, yet there is a way to avoid the scenario Maryna described. Ukraine should become an alternative in processing and refining of minerals that are extracted on Ukrainian soil and abroad – especially those used in electronics and semiconductors manufacturing: lithium, titanium, cobalt, copper, graphite, nickel, silicon, and rare earth elements. Currently, Ukraine doesn’t have the processing plants and lacks resources to build them; therefore, we should convince the EU and US that it’s in their best interest to invest in building plants and import necessary heavy machinery, as the paper from Ukrainian branch of Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung foundation suggests.

But minerals are just part of the bigger problem. We are also dependent on Chinese manufacturing of electronics, integrated circuits (IC) and semiconductors because for decades Western countries and companies have been offshoring the manufacturing and production to China for the sake of cutting the costs via cheaper labor and resources while increasing the profits. Apple’s contribution to the Chinese electronics sector, as described in Patrick McGee’s book Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company, is the biggest one and even compared to a nation-building effort.

Over the course of history, the military and state-sponsored research was the main accelerator behind science and technology innovations. My personal favourite example is cryptography: while encrypting techniques have been practiced for centuries and mostly used for military purposes, after two World Wars and the stories of Enigma encrypted messages a new era of encryption algorithms started. New cryptography algorithms emerged with the help of National Security Agency (NSA) research, and the usage of encryption was spread to commercial products in order to protect customers' data.

Taiwan’s rise in the technology sector in the 1970s and 1980s from the nation of home workshops should serve as a lesson for Ukraine. By creating publicly funded Hsinchu Science Park and the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) and establishing supportive governmental regulations, Taiwan has become one of the worldwide leaders in technology R&D whose contributions to science and innovation have been globally recognised. On top of that, ITRI’s innovation-friendly environment incubated successful startups and companies both in the public and private sector: United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) were created as the Institute's spinoffs. Their commercial and technological success allowed Taiwan to surge ahead as a global semiconductor hub, which helped to revitalise the economy and produce massive growth. An important element of success was investment in training of engineers who later became the industry pioneers: since 1976, ITRI had been sending them to the United States for training in integrated circuit designing, manufacturing and testing. Amongst those who completed training in the USA was Robert Tsao, founder of UMC. While Morris Chang received education in MIT and worked at Texas Instruments as an engineer decades before ITRI was created, his experience and leadership as ITRI president since 1985 helped achieve a key breakthrough in chip production; two years later, Chang founded TSMC that is now the world’s largest and most advanced semiconductor foundry. Those ITRI trainees are the kind of engineers Ukraine has now with experience in repairing, and could gain a lot from overseas training.

Members of the Technical Advisory Committee, a board of Chinese-American researchers and engineers that steered the development of Taiwanese technology & IC industries and helped recruiting and training engineers for ITRI. Photo was taken in 1977

There have been some steps in the right direction, for now in military research and production – specifically, with drones and satellite terminals with the help of Western companies. But the Ukrainian government should go much further and radical, and abandon its neoliberal approach of privatising key industries and staying dependent on private companies and R&D labs. Instead, a public research institution must be established in Ukraine that will drive industrial development and technological advancement, fosters creation of Ukrainian companies which will offer innovative solutions and help growing local economy and industries, and partner with Western, South Korean and Taiwanese companies and institutions (especially Taiwan who is a steadfast supporter of Ukraine and currently in preparation itself for a Chinese invasion). Exchange programs and overseas training for Ukrainian engineers will also be extremely beneficial. Of course it doesn’t mean Ukraine should copy every single measure Taiwan is doing: there are differences in production costs and government regulations; also, wages of Taiwanese workers are currently stagnating and causing depression among Taiwanese youth.

Nonetheless, the approach of state-driven research institutions, electronics manufacturing and production sectors, and significant public investment in R&D will help Ukraine become one of the leaders in the technology and manufacturing sectors, and a key partner of East Asian democracies. The foundations are there; all that's needed is a political will.

Footnotes

- ^ David Sheff “Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children”, pages 214-217.