On September 22, during President Volodymyr Zelensky’s visit to the Canadian Parliament, the audience gave a standing ovation to 98-year-old Yaroslav Hunka, who was invited by Parliament Speaker Anthony Rota. Rota introduced the guest as a “hero of Ukraine and Canada” who “fought for Ukrainian independence against the Russians.” As it turned out, Hunka was a veteran of the Waffen SS “Galicia” Division (hereinafter, the Division), a Nazi armed formation of 1943–1945.[1]

This caused outrage among a number of political and public associations in Canada, including Jewish organizations. Poland’s Minister of Education initiated an investigation into Hunka’s possible crimes “against the Polish people and Poles of Jewish origin.”

As a result, Speaker Rota first apologized and then resigned. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau also apologized for the incident, calling it a “mistake” that shocked Jews, Poles, Roma, the LGBT community, and other groups who suffered under Nazism during World War II. Canada sent an official apology to Zelensky through diplomatic channels.

However, in Canada, this political scandal has sparked a broader discussion[2] about postwar immigration policies that turned the country into a haven for Nazi criminals. Calls are growing for declassification of government documents related to entry permits to Canada for people who belonged to various armed formations of the Third Reich.

The Ukrainian authorities decided not to fuel the scandal with official statements. However, the “Hunka case” was actively discussed in Ukrainian society and spawned a new wave of glorification of the Division in general and Hunka in particular. And not only by right-wing radical political forces, which are longtime apologists for the Division. Some liberals became unexpected advocates for the Division, accusing the notional West of ignorance and misunderstanding of Ukraine’s complex history, blaming Westerners for “mythological thinking” and uncritical attitude toward Soviet/Russian propaganda.

“So how do we explain to them that for us, 98-year-old Division veteran Yaroslav Hunka is a hero?”, journalist Yuriy Makarov asks rhetorically, without explaining what sociological surveys give him the gall to make such generalizations. After all, Makarov dares to speak not only on his own behalf, appealing to the collective Ukrainian “we.”

The aim of this article is not to analyze the complex history and legacy of the Waffen SS “Galicia” Division. Rather, it seeks to answer the question of why it should not be glorified.

Yaroslav Hunka (giving a thumbs up) during applause in the Canadian Parliament, September 22, 2023. Photo: YouTube/CBC News: The National

“They Fought for Ukraine”

Undoubtedly, the Germans and Ukrainians had different views on the Division’s purpose and objectives. While the former viewed it as an instrument of their own geopolitical and military interests, the latter, at least some of them, at the stage of the Division’s creation, were inclined to romantic visions of its role in the future Ukrainian statehood. These illusions, as well as attempts to justify the alliance with the criminal Nazi regime, formed the basis of the postwar heroic myth that the Division “fought for Ukraine.” This myth is still alive today, despite the fact that the division’s members, partly voluntarily and partly under duress, helped the enemy German army and carried out Nazi orders.

The division was created by the Nazis during their occupation of Ukrainian lands in July 1943. Its military and ideological training was provided by the Nazis and its main commanders were Nazis. The Division’s soldiers wore German uniforms with runes and other Waffen SS insignia.[3] They swore an oath to Adolf Hitler, not to the Ukrainian people. The meaning of this oath was explained to the new recruits by the governor of the District of Galicia, Otto Wächter. In December 1943, he attended oath ceremonies in various training camps of the Division, where he emphasized that they promised obedience to Hitler as Führer and commander-in-chief of the armed forces of Nazi Germany, as well as the builder of the “New Europe.”[4]

Parade of recruits of the Waffen SS “Galicia” Division in Lviv. In the foreground is the head of the Military Administration, Col. Bisanz. July 18, 1943. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The political and military leadership of the Third Reich did not promise the members of the Division to support the idea of a Ukrainian state and showed their real attitude to it in 1941 by repressing those who proclaimed the Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State in Lviv. Keeping this in mind, the members of the Division still hoped that through their service they would be able to receive the military training necessary for the formation of a full-fledged Ukrainian army.[5] They were also attracted to the idea of fighting Bolshevism, which was considered the greatest enemy and “executioner” of the Ukrainian people.

Thus, regardless of how individual members of the Division perceived the meaning and ultimate goal of their service, it was in fact to serve the interests of Nazi Germany. They suffered and died for these interests and carried out orders that are difficult to reconcile with Ukrainian national interests. This applies to the Division’s fight against the anti-Nazi resistance movement in Slovakia and Slovenia.

Moreover, the Division fought with the Red Army, in whose ranks about 6–7 million Ukrainians served during World War II. Therefore, this confrontation fits more into the concept of a fratricidal war and the tragedy of the Ukrainian people than into the heroic myth of the “fight for Ukraine.”

Oath of allegiance of the Waffen SS “Galicia” Division. Photo: NAC

The Division and the Holocaust

The Waffen SS “Galicia” Division was not formed to implement the Nazi extermination policy toward Jews. However, at certain stages, the Division was infused with members from various Nazi armed formations, some of which participated in the Holocaust.[6] Not to mention that the German commanders of the Division had experience with anti-Jewish violence, such as SS Oberführer Fritz Freitag.

The question of the Division’s participation as a unit in anti-Jewish violence remains open. For example, researcher of Holocaust in Galicia Dieter Pohl emphasizes the high probability that the Division’s members participated in the raids on Jewish survivors in Brody in February 1944.[7] They also carried out punitive actions in Slovak villages where Jews sought refuge. In January 1945, they searched Podhorie, where eight Jews were hiding.[8]

It is difficult to say how ideologically motivated the actions of the Division’s members were. During their training, they were introduced to Nazi racial theory. But even before that, they had seen it in practice. During 1941–1943, they saw pogroms, ghettos and labor camps, and mass shootings of their Jewish neighbors: women, men, and children. Even after there were almost no Jews left in Galicia, the main paper of the Division, the Military Administration’s weekly Do peremohy (To Victory), considered it appropriate to use anti-Semitic propaganda to motivate soldiers. The claim about “*ike Bolshevik communism” runs like a red thread through its publications. The weekly regularly published cartoons depicting Red Army officers of stereotypical “Jewish” appearance.[9] The paper published anti-Semitic folk sayings portraying Jews as exploiters and oppressors of the Ukrainian people, and expressed joy that “German troops have already driven away Isaac.”[10]

It is hard to imagine that such propaganda had no effect on the Division’s members. If it did not generate hatred, it certainly generated indifference. This indifference is noticeable even years later. For example, Yaroslav Hunka, who was welcomed to the Canadian Parliament, in his memoirs published in 2011, calls the first two years of the German occupation of Berezhany, where he studied, “the happiest years” of his life. He does not mention the fate of his Jewish neighbors at all. Although almost every third resident of Berezhany as of 1941 was Jewish, and the total number of Jews in the town was about 4,000, less than a hundred of them survived the Holocaust. Some of the Jews of Berezhany were deported to Belzec by the Germans and their collaborators, while others were shot in their homes, on the streets, in the local ghetto, and at the Jewish cemetery.[11]

SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler with Otto Wächter and other German officers in front of the SS “Galicia” Division, 1943. Photo: Wikimedia

War Crimes

One of the most controversial pages in the history of the Division is its involvement in war crimes. Contemporary researchers rightly note that the Division is often accused of crimes in which it as a structure was not involved. For example, they are blamed for the crimes committed by the Galician SS Volunteer Regiments (Galizische SS-Freiwilligen Regiment), comprised of men who volunteered for the Division but were not enrolled due to lack of vacancies. They were also commonly called “our SS” or “riflemen” and wore distinctive insignia with “lions,” the same as the Division’s emblem.

In March 1944, 4th Galician SS Volunteer Regiment killed 50 Polish civilians in Zawonia and burned down the village. The regiment committed similar crimes in the villages of Pidkamin and Palykorovy. It was also involved in the destruction of Huta Pieniacka on February 28, 1944, where, according to various sources, 500 to 1000 women, men, and children were killed.[12] The 4th SS Regiment was not a part of the Division when it committed crimes against the Polish population of Galicia, but it became one in June 1944.[13]

A similar picture can be seen in the case of the Ukrainian Self Defense Legion, which the Germans called the 31st SD Battalion. It participated in anti-Polish actions on Ukrainian territory, as well as in the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. It was merged with the Division in March 1945.[14]

But did the Division as a unit commit war crimes? This question is answered by research analyzing its participation in the suppression of the national uprising and partisan movement in Slovakia. During their fight against the underground, the members of the Division conducted searches and arrests, committed murders, engaged in looting and burning of houses in the villages of Smrečany and Žiar na Liptove, and in the city of Žilina.[15] On October 16, 1944, in the village of Plešivá, the Division’s members killed three civilians, including a two-year-old girl. In Radôštka, they killed and robbed a man who was hiding partisans.[16] According to some reports, during its retreat from Slovakia in January 1945, the Division, acting on the orders of the Germans, took horses and carts from the population.

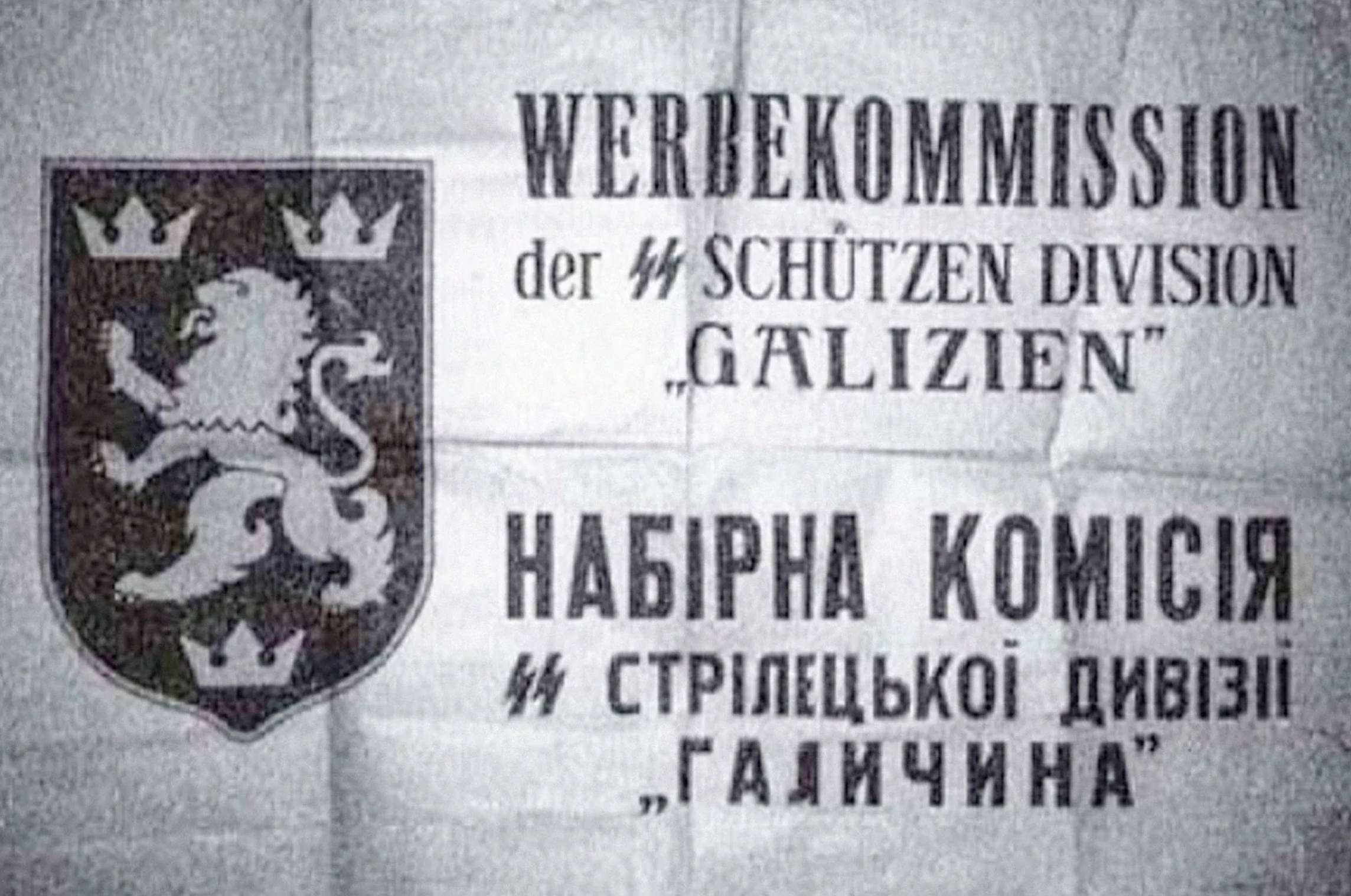

A sign at a recruiting station for volunteers for the SS “Galicia” Division, 1943. Photo: Wikimedia

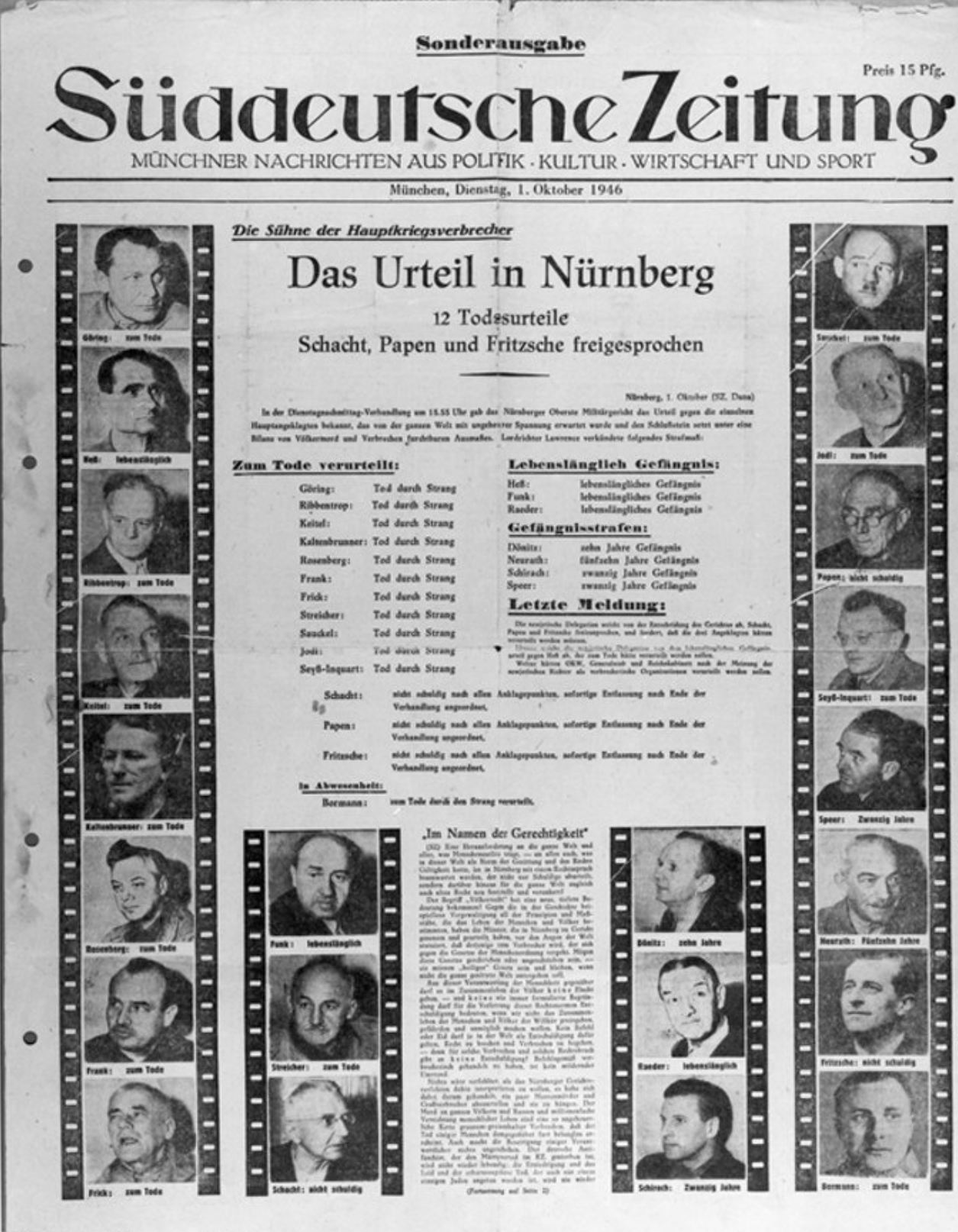

The Nuremberg Tribunal

There is a widespread belief that the Waffen SS “Galicia” Division was “not convicted” or even “was acquitted” by the Nuremberg Tribunal (hereinafter, the Tribunal). It is worth noting that at the beginning of its work, the Tribunal indicted a number of military, political, and public organizations of Nazi Germany, but eventually only a small part of them was convicted. Among those that were indeed recognized as criminal organizations was the Waffen SS, which, according to the Tribunal, was “in theory and practice an integral part of the SS.” Therefore, despite the fact that during part of the war the Waffen SS divisions acted as part of the army, they were organizationally subordinated to the SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler.

The court materials indicate that the Waffen SS was “involved in the widespread murder and ill-treatment of the civilian population of occupied territories Under the guise of combating partisan units, units of the SS exterminated Jews and people deemed politically undesirable by the SS, and their reports record the execution of enormous numbers of persons. […] Units of the Waffen SS were directly involved in the killing of prisoners of war and the atrocities in occupied countries. It supplied personnel for the Einsatzgruppen, and had command over the concentration camp guards after its absorption of the Totenkopf SS, which originally controlled the system.”[17]

In its judgement, the Tribunal stated the following:

The SS was utilised for the purposes which were criminal under the Charter involving the persecution and extermination of the Jews, brutalities and killings in concentration camps, excesses in the administration of occupied territories, the administration of the slave labour programme and the mistreatment and murder of prisoners of war. […] In dealing with the SS the Tribunal includes all persons who had been officially accepted as members of the SS including the members of the Allgemeine SS, members of the Waffen SS, members of the SS Totenkopf Verbaende and the members of any of the different police forces who were members of the SS.

Thus, in 1946, the Nuremberg Tribunal recognized the Waffen SS as a criminal organization. This decision applied to all 38 Waffen SS divisions, including the Galician division. This, in turn, gave grounds for further criminal prosecution of Waffen SS members in the national courts of individual countries.

Report on the verdict of the Nuremberg Tribunal. Süddeutsche Zeitung. October 1, 1946. Photo: Wikimedia

“The Deschênes Commission”

One of the most common arguments in defense of the Division is the reference to the findings of the so-called “Deschênes Commission.” The Commission began its work in 1985 as the the Commission of Inquiry on War Criminals in Canada (hereinafter, the Commission). It was headed by Jules Deschênes, a judge of the Superior Court of the Province of Quebec. In its 1986 findings, the Commission stated that the Waffen SS “Galicia” Division “should not be indicted as a group;” the members of the division had been vetted before entering Canada, war crimes charges against the Division had never been substantiated, either in 1950 or 1984, and mere membership in the Division was not sufficient to warrant prosecution.

The problematic nature of the Commission’s conclusions is confirmed by a report by researcher Alti Rodal. In 1986, she conducted a study specifically for the Deschênes Commission on Nazi war criminals in Canada. The authorities censored her report and published an incomplete version. Currently, the Canadian government is considering declassifying these materials due to public pressure after the Hunka case.

Alti Rodal emphasized that despite the fact that the Commission had no evidence of war crimes committed by the Division as a group, individual members of the Division could have committed them. After all, after the Division’s defeat in the Battle of Brody in July 1944, 12,000 new members were added to the Division (in addition to the 3,000 survivors). Among them were members of various police units which had committed war crimes.[18]

Alti Rodal also pointed out that the Division’s members had not been thoroughly screened before arriving in Canada, as the government claimed.[19] In 1948, the United Kingdom sent a secret communiqué to six Commonwealth countries, including Canada, calling for an end to the prosecution of Nazi war criminals, arguing that “the time has come to bury the past.”[20] Canadian policy in the following years shows that this recommendation was well received. In 1950, Canadian immigration policy was liberalized. This allowed members of the Waffen SS to enter Canada in 1951 and members of the SS to do so in 1955. This “open door policy” was driven by the Cold War. Western countries were then more willing to identify communist spies than to punish Nazi criminals. In the eyes of the government, the members of the Division were true anti-Communists, and therefore loyal citizens of the state.

It is worth noting that the Commission’s conclusions were based on a limited number of documents that did not provide a holistic view of the Division’s activities. In particular, it did not have access to documents from the USSR and the Warsaw Pact states. The long negotiations with the Soviet Union regarding access to original documents and the interviewing of dozens of witnesses ended in nothing. The Commission did not send its representatives to the USSR, citing the Soviet side’s delays and, consequently, lack of time.[21] However, modern research on the Division’s possible crimes is based mainly on documents from Eastern Europe, i.e. those that the Deschênes Commission did not consider in the first place.

Soldiers of the SS “Galicia” Division with anti-tank weapons, March 1944. Photo: Wikimedia

Official Discourse

While some right-wing nationalist groups in Ukraine consistently glorify the Division and organize marches in its honor, it remains the subject of a regional, Galician cult. Some of the soldiers currently defending Ukraine from Russian aggression wear chevrons with “lions,” trying to emphasize the tradition of the Ukrainian liberation movement against the Kremlin. This simplification obscures the uncomfortable fact of the Division’s collaboration with the Nazis, which is nevertheless sufficient reason for the state of Ukraine to avoid glorifying the Division at the legislative level.

The Law of Ukraine “On the Legal Status and Honoring the Memory of Fighters for Ukraine's Independence in the Twentieth Century” indicates an extensive list of authorities, organizations, units and formations whose members are considered “fighters for the independence of Ukraine.” The Waffen SS “Galicia” Division is not on this list. The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine did not include it in this list even after a corresponding appeal from the Lviv Oblast Council on February 16, 2021. Thus, as of today, the state of Ukraine does not consider the Division’s members to be fighters for Ukraine’s independence.

The key memorial actor, the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory (UINM), represented by its leadership, opposed the glorification of the Division. For instance, in 2018, the former director of the UINM, Volodymyr Viatrovych, stated that “the anniversary of the creation of the Galicia Division is not a holiday for Ukrainians.” In 2021, when a march in honor of the Division was held in Kyiv, the then head of the UINM Anton Drobovych emphasized: “The glorification of SS troops is unacceptable for a European country.”

March on the 78th anniversary of the SS “Galicia” in Kyiv, April 28, 2021. Photo: Victoria Roshchyna/hromadske

At the same time, on September 27, the acting Minister of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine Rostyslav Karandeiev inaugurated a photo exhibition “Storm of Steel” at the Kyiv History Museum. It combines photos of various military formations on the territory of Ukraine in previous centuries and their modern counterparts, recreated by soldiers of the Third Separate Assault Brigade[22] who are currently defending Ukraine from Russian aggression. The presence of a photo of the Division’s soldiers might seem like an unfortunate mistake and negligence on the part of the exhibition’s organizers. However, on October 3, fighter of the 3rd Assault Brigade Oleksii Rains, alias Consul, emphasized in his telegram channel: “The Galicia Division are heroes […], they, like us, were fighting for what is right.”

Such careless parallels and generalizations diminish the crimes of the Third Reich by focusing exclusively on its anti-Bolshevik policies. However, millions of people became its victims in Ukraine alone: Jews, Ukrainians, Roma, prisoners of war, people with mental illness, and Ostarbeiters. The memory of Babyn Yar, Drobytsky Yar, Koriukivka, and thousands of other places of mass crimes should be a safeguard against the rehabilitation of Nazism.

Moreover, the glorification of the Division challenges the Western model of memory of World War II and the Holocaust, which is based on the condemnation of the ideology and practices of the Nazi regime. Calling the members of the Division “riflemen,” deliberately avoiding the full name of the Division, which shows its affiliation with the SS, and glorifying the Division as a whole or its individual soldiers are signs of this dangerous manipulation of memory. It obscures the crimes of Nazism by offering a kind of “lesser evil” trap. Its essence is to justify the situational alliance of a part of the Ukrainian society with the Nazis as a “lesser evil,” which could have made it possible to defeat the “greater evil,” embodied by the Soviet regime.

The danger of this trap lies in selective memory, focusing on one’s own interests, insensitivity to the pain of others, and thus justification of violence against individuals, communities, and nations. All this harms the democratic development of modern Ukraine, creates divisions and enmity, and weakens the discourse on the value of human life and human rights.

The glorification of the Waffen-SS “Galicia” Division leads Ukrainian democracy to a dead end.

Footnotes

- ^ In April 1945, it was renamed the First Ukrainian Division of the Ukrainian National Army.

- ^ Notably, the University of Alberta returned the Hunka family’s donation and expressed regret for the “unintended harm caused.”

- ^ Margolian, Howard. Unauthorized Entry: The Truth About Nazi War Criminals in Canada, 1946-1956. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000, 132.

- ^ Do peremohy. 23 December 1943. In the spring of 1945, the soldiers of the Division took another oath.

- ^ Shkandrij, Myroslav. In the Maelstrom: The Waffen-SS “Galicia” Division and Its Legacy. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023, 7.

- ^ Rudling Per Anders, ‘They Defended Ukraine’: The 14. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS (Galizische Nr. 1) Revisited, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 2012, 25:3, 344.

- ^ Dieter Pohl, Nationalsozialistische Judenverfolgung in Ostgalizien 1941–1944: Organisation und Durchführung eines staatlichen Massenverbrechens, Munich: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1997, 365.

- ^ Šmigeľ Michal, Cherkasov Aeksandr, The 14thWaffen-Grenadier-Division of the SS «Galizien No. 1» in Slovakia (1944–1945): Battles and Repressions, Bylye Gody. 2013. № 28 (2), 66.

- ^ Do peremohy, 6 January 1944; Do peremohy, 9 March 1944.

- ^ Do peremohy, 30 March 1944.

- ^ For more information about the Holocaust in Berezhany, see: Redlich, Shimon, Together and Apart in Brzezany: Poles, Jews, and Ukrainians, 1919–1945. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

- ^ Motyka Grzegorz, Dywizja SS “Galizien” (“Hałyczyna”), Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość 1/1, 2002, 114–115.

- ^ Motyka Grzegorz, From the Volhynian Massacre to Operation Vistula. The Polish-Ukrainian Conflict 1943-1947, Brill: 2022, 176.

- ^ Melnyk, Michael James. The History of the Galician Division of the Waffen-Ss. Stroud: Fonthill, 2016. (online version).

- ^ Fremal K. 14. Waffen-Grenadier Division der SS (GalizienNo. 1) v historickej spisbe o slovenskom hnutí odporu v rokoch druhej svetovej vojny. In: Slovenská republika 1939–1945 očami mladých historikov IV. Eds. M. Šmigeľ, P. Mičko. Banská Bystrica, 2005; Šmigeľ Michal, Cherkasov Aeksandr, The 14thWaffen-Grenadier-Division of the SS «Galizien No. 1» in Slovakia (1944–1945): Battles and Repressions, Bylye Gody. 2013. № 28 (2), 66–67.

- ^ Šmigeľ Michal, Cherkasov Aeksandr, The 14thWaffen-Grenadier-Division…, 67.

- ^ Bd. 22, S. 586. (Zweihundertsiebzehnter Tag. Montag, 30. September 1946, Nachmittagssitzung), online.

- ^ Khromeychuk, Olesya. “Undetermined” Ukrainians. Post-War Narratives of the Waffen SS “Galicia” Division. Bern: Peter Land, 2013, 74. The Deschênes Commission investigated only 218 officers of the Division with regard to their activities in 1941–1943.

- ^ For more information on why the soldiers of the Division managed to easily get to Canada, see: Rodal, Alti. “How Perpetrators of Genocidal Crimes Evaded Justice: The Canadian Story.” In Remembering for the Future. The Holocaust in an Age of Genicide, Vol. 1, ed. by J. K. Roth and E. Maxwell, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001, 702–725.

- ^ Cotler Irwin, Bringing Nazi War Criminals in Canada to Justice: A Case Study Proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American Society of International Law), April 9–12, 1997, Vol. 91, 263.

- ^ Fletcher, George, Friedlander, Henry and Fritz Weinschenck, Canadian Responses to World War Two War Criminals and Human Rights Violators: National and Comparative Perspectives, 8 B.C. Third World L.J. 34, 1988, 34–45.

- ^ The brigade is formed around veterans of the Azov Movement and is led by the leader of the National Corps party Andriy Biletsky.

Author: Marta Havryshko

Translation: Pavlo Shopin

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva

French translation: Entre les lignes entre les mots

Spanish translation: Entendiendo Ucrania