Oleksandr (Alexander) Dovzhenko may be considered the most famous Ukrainian director of the twentieth century. Ukrainian and foreign researchers have written a great number of studies dedicated to him. Most of them form roughly the same image of Dovzhenko: a lone national genius, the only “Ukrainian director” of his time, and a peasant poet who “emerged from the masses.” Although the cultural policy of the USSR mainly created this image, it was also rooted in the foreign critical community.

Yet, did Dovzhenko’s work really come out of nowhere? In this article, I show the way the image of Dovzhenko was constructed and explore the background in which the director was formed. For this purpose, I analyzed publications about Dovzhenko in Soviet and foreign periodicals and talked to Oleksandr Teliuk, head of the Dovzhenko Centre’s film archive.

First reviews of Dovzhenko’s films: a bad socialist or a director “from the masses”?

Dovzhenko’s first films, such as Vasya the Reformer, Love’s Berry, and The Diplomatic Pouch, failed to bring much attention to his work. Only after Zvenyhora (Zvenigora) was released did Dovzhenko become well-known in film communities in the USSR and abroad. This film marks the beginning of the so-called Silent Trilogy, including Arsenal and Earth. It was the films of the Silent Trilogy that made the director famous[1]. Many Soviet newspapers and magazines published reviews of Zvenyhora, including New Generation (Nova Generatsia), a periodical that was considered as the leading in the context of the Ukrainian avant-garde, and Kino, a magazine founded by the All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Administration (VUFKU). The reviews by those of the “Executed Renaissance” were published on the pages of these periodicals.

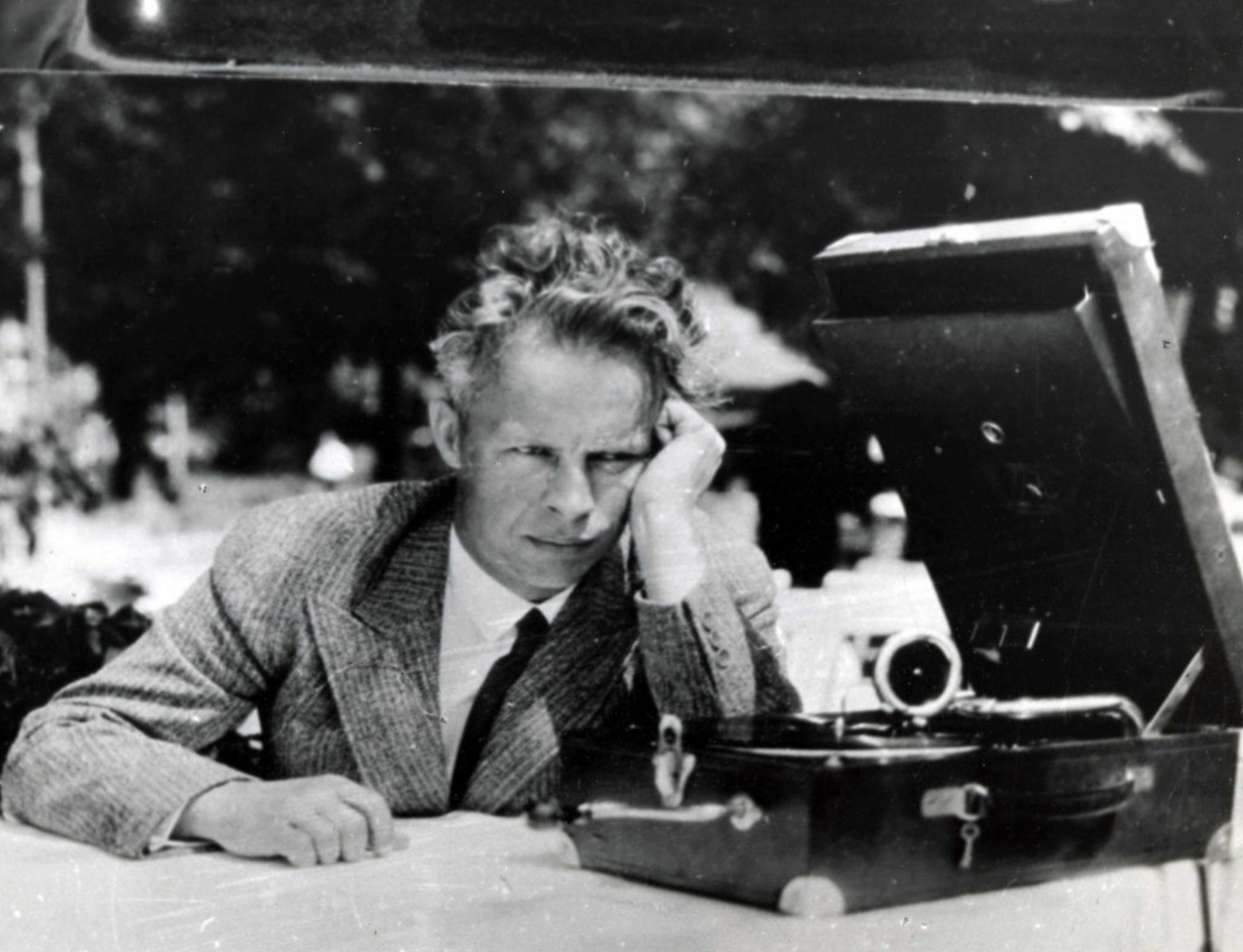

Oleksandr Dovzhenko. Photo: open sources

For example, Kino published a review by Mykola Bazhan entitled Legends and History. In this review, Bazhan argues that Zvenyhora has brought Ukrainian cinema to a new level. He refers to the piece as an “original film” that develops its own unique poetics rather than borrowing imagery from Russian and European films. In his review, Bazhan, of course, talks about the portrayal of the peasantry as a class, but for him, Zvenyhora is far from being limited to the depiction of class conflict[2]. In his publication Notes. Zvenyhora, he writes about both the irony and lyricism of Dovzhenko's films[3]; later on, he emphasizes the same point in his review of the film Arsenal[4].

Leonid Skrypnyk, in his review published in the New Generation, argues that Dovzhenko’s Zvenyhora marked the beginning of the Ukrainian cinema. Skrypnyk writes that this film is the first Ukrainian film due to the introduction of its own cinematic language. He analyses the meaning of Dovzhenko's techniques, looking at them through the perspective of film theory[5].

However, strictly pro-party periodicals such as Kharkiv Proletarian[6] and Communist Revolution[7] featured anonymous reviews in which Zvenyhora was called obscure for working-class people and, therefore, a failure. Indeed, the audience at that time was not ready to understand Zvenyhora since the language of Ukrainian cinema, which had just begun to appear, was new to the public. As Borys Zahorsky notes in his article in Kino[8], the audience had to be taught to understand this language. So, there were both favorable and entirely negative reviews of Zvenyhora.

Stills from the film Zvenyhora

A similar situation happened with Dovzhenko's film Arsenal. Mykola Bazhan, for example, admired the film's lyricism and emotional depth[9]. Valerian Polishchuk, in his review[10], as well as Ivan Eisenberg in his Your word, comrade workers review in Kultrobotnik[11], both criticized Arsenal for its lack of "clarity" in the eyes of the masses.

After the release of Earth, the conflict over the “insufficient socialism” of Dovzhenko’s films reached its highest point. The film was released at a time when Stalin's censorship was strengthening, following the discussion of "khvylovism"[12] and the first arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals. The film received much positive feedback. Yakiv Savchenko's review in the magazine Kino admired Earth, referring to Dovzhenko as an expressionist, a master of cinema who poetically expressed socialist themes. Savchenko argued that the film's shot composition and philosophical intentions were harmonious[13]. In his review, also published in Kino, Vasyl Levchuk called Dovzhenko the first Marxist artist and Earth the first Materialist film[14]. In many earlier reviews, this film is seen as the high point of Dovzhenko’s creative growth[15].

Yet, after Demyan Bednyi's satirical poem Philosophers, a large wave of criticism arose. This poem ridiculed the film for its lack of positive portrayal of Soviet reality, excessive biological determinism, and for its lack of negative portrayal of kulaks and priests[16]. Articles in Pravda[17] and Kino i Zhyttia[18] also pointed out Earth's flaws. In these articles, Dovzhenko was portrayed to be an excessive aesthete, an elitist, and, according to Bednyi, a supporter of the kulaks. At best, Dovzhenko was perceived as a director who had lost his way. Shortly after, the film was cut by the censors. Many Soviet magazines and newspapers criticized Earth for its excessive obsession with nature[19]. Eventually, nine days after the censored version was released, the film was banned from being shown altogether.

Oleksandr Dovzhenko (right) and Danylo Demutskyi are working on the film Earth, selecting the camera position for the best shot. Photo: DR

The first Ukrainian reviewers, who were often Dovzhenko’s friends and acquaintances, wrote about him as a genius and the first Ukrainian director, and at the same time, a director of the new socialist cinema. Moreover, they began to talk about the poetic nature of his works. In addition to this, in their articles, Dovzhenko’s films appeared framed in the context of the ideas of the Ukrainian avant-garde. At the same time, Communist Party periodicals immediately began to criticize his films for their lack of comprehensibility for the masses. This criticism only intensified after the release of Earth, with accusations of “ideological deviations” being added to it.

Meanwhile, a different perception of Dovzhenko's work developed in Europe and the United States. Earth was watched abroad even after it was banned in the USSR. All the films of the Silent Trilogy would become well-known in Europe and the USA immediately after their release. The critics’ reactions abroad were somewhat different from those in the Soviet Union. Articles by Yevhen Deslav[20] and George Clarke[21] in the magazine Kino indicates that Zvenyhora has become a huge success in Paris and New York.

“In terms of its style, Zvenyhora is a European film,” says Oleksandr Teliuk, head of the Dovzhenko Centre's film archive. “Dovzhenko, as a young director, was imitating the achievements of European cinema, in particular, The Nibelungs and the films of Abel Gance. So the European audience and critics could understand the language of Zvenyhora and admired it.”

The same goes for Earth, which was shown abroad even after it was banned in the USSR. European and US audiences were able to see the full version of the film uncensored. However, eight days after its release, the film was removed from cinemas to cut out the most “provocative” scenes. These included a scene in which peasants were cooling a tractor by urinating and a scene in which the protagonist’s bride rips off her clothes in despair.

Still from the film Earth, which was banned by the censors

The article Earth by Paul Rotha, which was later included in his collected works entitled Celluloid, is proof of the European film critics’ admiration for Dovzhenko’s films. Rotha wrote about both Zvenyhora and Earth. He argues that Dovzhenko’s films differ from all the other Soviet films in that they have “as little propaganda as possible.” He portrays the director as a lone genius, a philosopher who questions and deals with life and death. Rotha also draws attention to Dovzhenko's peasant roots in the context of his connection to the folklore and refers to his films as “poetry.”[22]

It can be summarized that the first Ukrainian reviews began to present Dovzhenko as a unique phenomenon of Ukrainian cinema. Although his films remained unclear to most of the Ukrainian audience, he became “one of theirs” for the European one. For European audiences and critics of the 1920s and 1930s, Dovzhenko both represented the Soviet regime and was a poetic filmmaker inscribed in the context of European cinema. At the same time, they knew almost nothing about the Ukrainian film avant-garde in particular and the art of the Ukrainian national Renaissance in general. Therefore, they had almost no understanding of Dovzhenko’s connection with these phenomena.

Construction of Dovzhenko’s image by critics of the second half of the twentieth century: lonely genius and poet of socialism

Foreign critics continued to analyze Dovzhenko's work in the 1960s. During this period, however, he was even more out of context. In his 1962 Histoire d’un art, the French film critic Georges Sadoul referred to Dovzhenko as the “first Ukrainian director” and saw him as the embodiment of national genius. He talks a lot about the lyricism of the Silent Trilogy, and Dovzhenko appears here as a naïve poet.

Yet Sadoul said nothing at all about the director’s relations to the Ukrainian avant-garde and the Ukrainian film community, nor did he mention the film's connection to European cinema when he wrote about Zvenyhora. The historical context of Dovzhenko’s films was also not covered by Sadoul: his article did not tell us anything about the Ukrainian Revolution or collectivization[23]. In other words, Dovzhenko appeared as a kind of naïve artist whose image lost any connection with his contemporary history and culture.

Still from the film Earth

In his 1988 work In the Service of the State, Vance Kepley contradicted this image of a naïve genius. However, he overestimated the director’s devotion to Soviet ideology and portrayed him as a poet in the service of the state. According to Kepley, all of Dovzhenko’s films had one main narrative: the depiction of Soviet progress. Kepley argued that glorifying this progress, not nature or folklore motifs, was the main purpose of Dovzhenko's work. For him, the latter was more of a background – the “old,” in opposition to which the “new” came into play. Kepley did not speak about Dovzhenko’s connection with the VAPLITE[24] (of which he was a member) and the Futurists, neither his views on national communism.

One should note that such an interpretation is possible not only because of ignorance of Ukrainian history in the early twentieth century. Both Sadoul and Kepley were sympathetic to the USSR, so their approach to Dovzhenko was based on these views. In particular, they both underestimated the impact of Stalin's repressions on the director's life and work. Sadoul spoke about the decline of Dovzhenko's talent after the Silent Trilogy but failed to give reasons for this decline. Kepley also did little analysis of the differences in Dovzhenko’s later films.

The historian George Liber noticed the distortion of Dovzhenko’s image created by Vance Kepley and tried to correct it in his monograph. He placed Dovzhenko in a sociopolitical context, emphasizing the ambiguity of the director’s views. Liber dwelled more on the Cossack origins of Dovzhenko's family and his supposed struggle against the Bolsheviks[25]. He portrayed the director as a tragic artist trying to escape repression and continue to live and create. It was a representation of individual struggle and drama alongside the tragedy of the whole society. Liber’s 1997 work also criticized the image (supported by Kepley) of Dovzhenko as a Soviet and avant-garde artist and yet couldn’t help but return to the stereotypical image of Dovzhenko as a poet and myth-maker[26].

This image has not changed much in the Western critical circles of the twenty-first century. Jonathan Rosenbaum, one of the contemporary film critics writing about Dovzhenko, calls the director “the most neglected major filmmaker of the 20th century.” Rosenbaum continues Sadoul’s tradition of associating Dovzhenko’s films with poetry and folklore while saying that they combine social irony and lyricism at the same time. He says nothing about the environment that formed the director[27]. Similarly, Dovzhenko’s seclusion is described by Chris Fujiwara in his 2002 article[28].

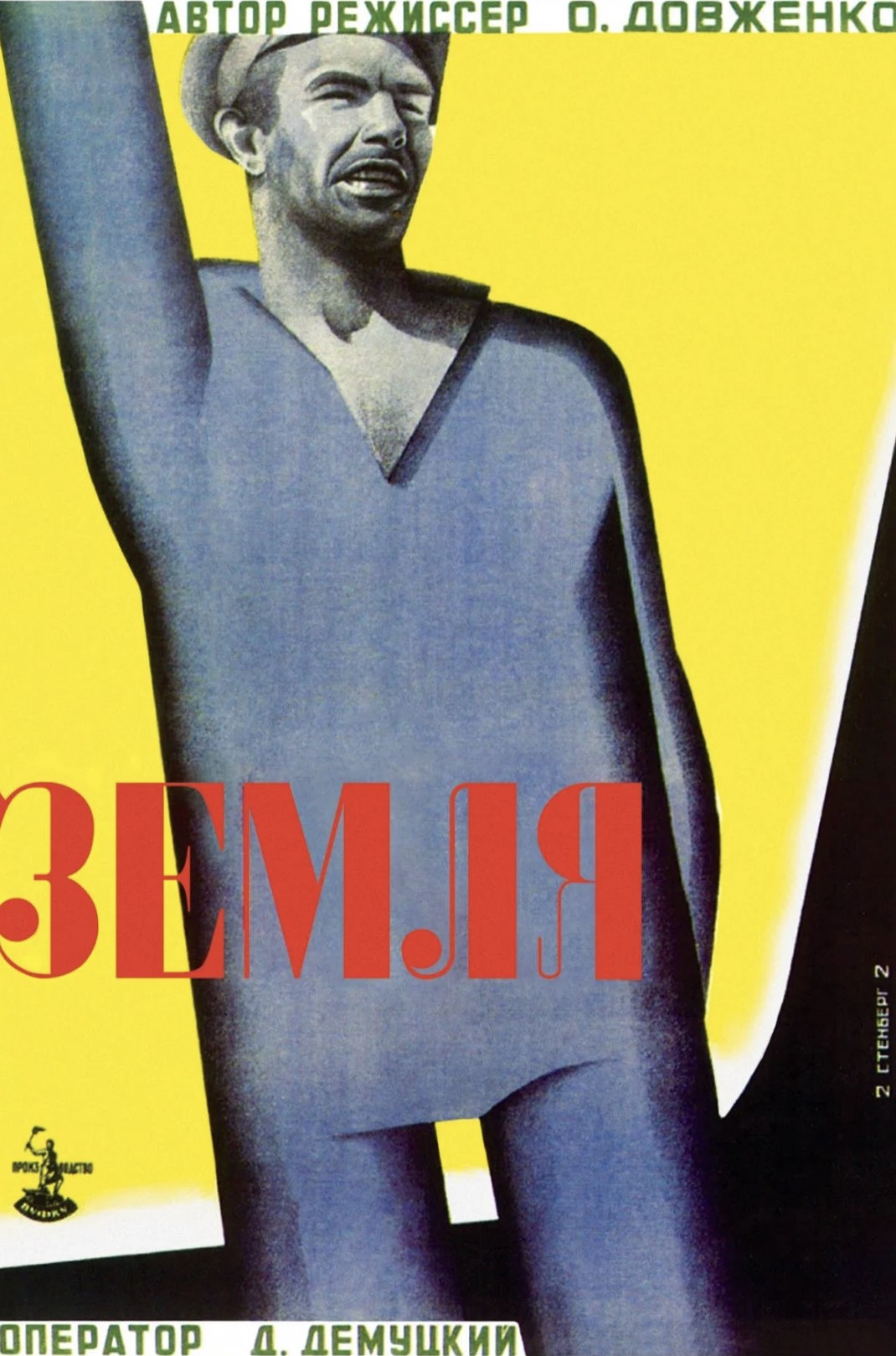

Poster for the premiere of the film Earth by the Stenberg brothers

So, in the studies of Western film critics and in the minds of Western audiences familiar with Dovzhenko, there has been no reflection on the connection between the director and his films on the one hand and the most significant events of Ukrainian history in the twentieth century on the other. This is especially true of the film Earth, which may be called the highlight of the director's work. Earth is undoubtedly a film on a commissioned topic with a positive image of collectivization, which does not cover the dekulakization and the Holodomor at all. However, it is the contrast between the historical background and the real events of that time that is important for understanding the film.

Oleksandr Teliuk explains:

“When I presented Earth to Western audiences, I emphasized this. I saw that this was something new, that no one associated the film with the historical realities in Ukraine at the time. This is due to the lack of knowledge about the Holodomor and the tendency of Western audiences to perceive poetry and cinematography first, rather than historical contexts, because they somehow complicate the perception of films.”

Similarly, most foreign viewers do not understand the connection between the Ukrainian Revolution and Arsenal because they are unfamiliar with this part of Ukrainian history. This unawareness only serves to reinforce Soviet stereotypes about Ukrainian history in the minds of viewers.

As early as the twentieth century, European film criticism established the perception of Dovzhenko as a lone national genius. The examples of Sadoul and Kepley show that there was no consensus in Europe about the image of the director. Still, he was rarely fully "returned" to his historical and cultural context. Therefore, contemporary Western audiences often lack an understanding of this context.

The Soviet press and literature contributed to the creation of such an image. “After the VUFKU was liquidated, the figure of Dovzhenko as an author was, on the contrary, consolidated in the Ukrainian press, and the director was even perceived as a political figure of the all-Soviet scale,” says Oleksandr Teliuk. Most Soviet sources also began to emphasize Dovzhenko’s peasant background to portray him as a “man from the masses.” At the same time, the fact that he studied in Germany was hardly mentioned.

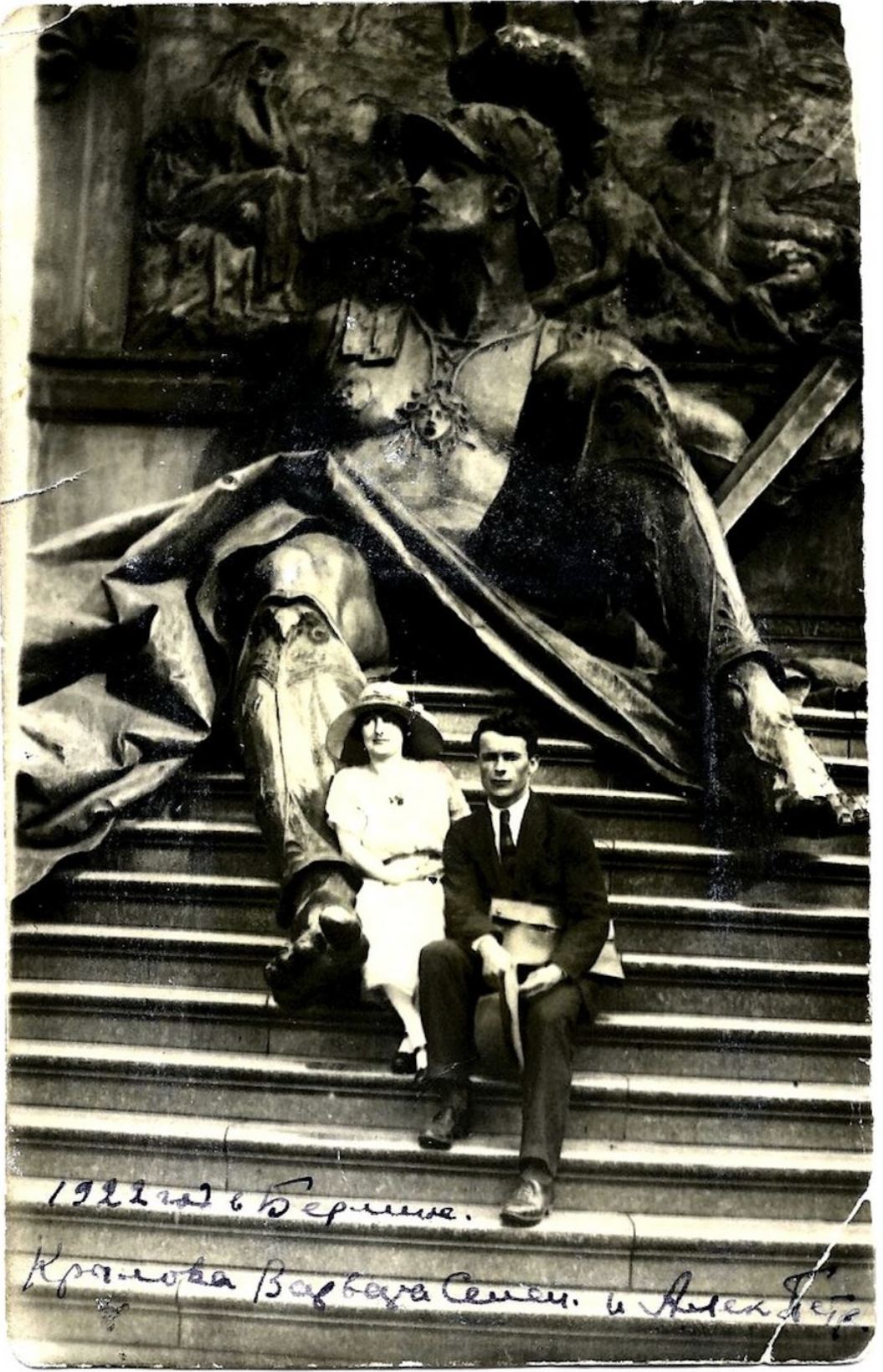

Oleksandr Dovzhenko with his first wife Varvara, Berlin, 1922. Photo: Suspilne.Kultura

Oddly enough, in the 1930s and 1950s, the Soviet newspapers referred to Dovzhenko as a Ukrainian filmmaker. One can find the origins of the image of the national genius in the first reviews of his films from Kino magazine, which I mentioned above. However, this was now a completely different image, and it replaced all the diversity of Ukrainian filmmaking in the 1920s. Under the influence of Soviet policies, this image spread abroad and also among the filmmakers of the Sixtiers, who considered Dovzhenko an inseparable part of Ukrainian cinema. He was associated with the appearance of poetic cinema, and Serhiy (Sergei) Parajanov, in particular, called himself the successor of Dovzhenko’s work. Due to ideological pressure, a new way of understanding the director's work could not take place. In the following years of the USSR's history, the same image of Dovzhenko, detached from the socio-cultural context, continued to prevail in film criticism and the mass imagination.

It is clear that the USSR emphasized Dovzhenko’s Sovietness and peasant origin in every possible way. This became an obligatory element of cultural policy towards all officially recognized Ukrainian artists in general and determined the image of the director abroad in particular. By doing so, the celebrated figure of Dovzhenko closed a gaping hole in the history of the Ukrainian SSR cinema that had emerged after Stalin’s repressions.

Are geniuses born or made? Dovzhenko and the VUFKU society

All the reviews and academic works of that time (and even contemporary ones) lacked and continue to lack a retrospective of Dovzhenko’s work and a comprehensive analysis of the socio-cultural environment from which he emerged. Almost all foreign, Ukrainian, and Soviet film critics consider Dovzhenko only as a solitary figure of a brilliant director. However, he was interlinked with other representatives of the Ukrainian avant-garde, particularly with the VUFKU film society.

One of the characteristics of the Ukrainian film society of the early twentieth century was its multidisciplinarity; it was composed of photographers, writers, visual artists, and literary figures. Les Kurbas, Ivan Kavaleridze, Yurii Yanovsky, and others were involved in this society. Dovzhenko himself created posters and caricatures before he started working at the film studio. The existence of such an environment is the achievement of the VUFKU leaders, who founded it in 1922. Multidisciplinarity arose for practical reasons as well. At that time, there were no higher education institutions in Ukraine where film-related specialists could study, so film technicians were often former peasants or workers. Meanwhile, more creative professions were the responsibility of specialists from related fields: writers, theatre directors, and photographers. This made Ukrainian avant-garde cinema a synthetic art. This particular characteristic brought it closer to the European avant-garde and distinguished it from the Russian cinema of the time.

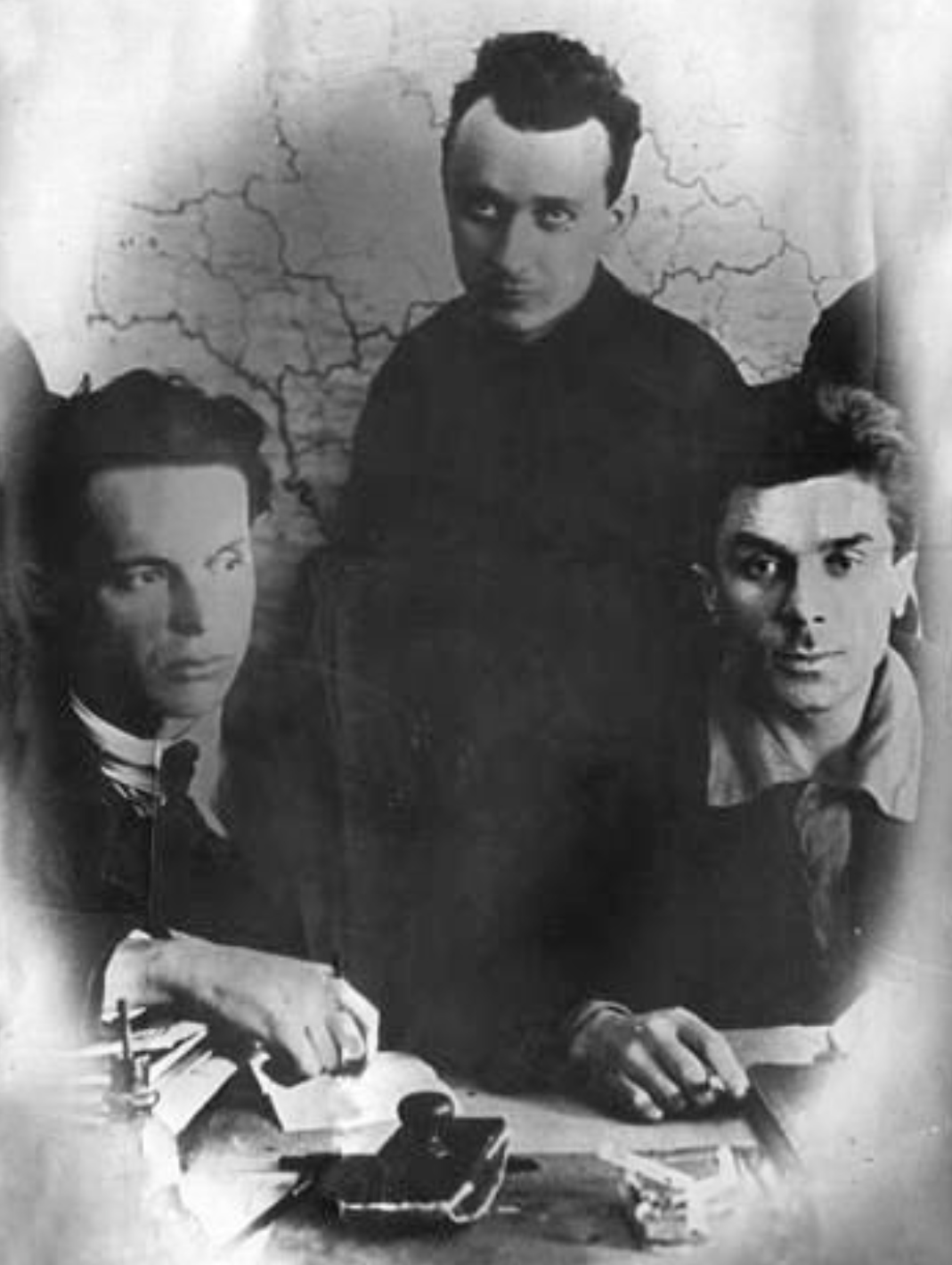

In the editorial office of the Vsesvit magazine (from left to right): Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Kost Hordiienko, Mykola Khvylovy, Kharkiv, 1925. Photo: open sources

It was VUFKU that made Ukrainian cinema successful abroad. Other Soviet republics did not have such a massive film production as Ukrainian, with only Moscow as a competitor. That is why the VUFKU film studios were often called “Ukrainian Hollywood.” Ukrainian filmmaking then differed from Russian because the VUFKU could make many decisions on the spot, and many representatives of the Ukrainian film society were integrated into European cinematography.

Since 1925, it has been possible to identify the influence of American and German films on Ukrainian filmmaking. The most significant influence came from Germany, which was the leader of European film production at that time. Both Vertov and Dovzhenko studied in Germany, and delegations from the VUFKU often traveled to the country. This connection could be observed at most in the avant-garde films. There was also the American influence, especially that of Charlie Chaplin's comedies. For some time, Chaplin himself was the representation of the USA for directors and critics. Dovzhenko created his first two lesser-known films, Vasya the Reformer and Love’s Berry, based on American comedies. His third film, The Diplomatic Pouch, attempted to create an equivalent of an American spy film. The VUFKU had reporters in Europe and the United States, and their articles were published in the Kino magazine. Foreign specialists, especially cinematographers, were even invited to work at Ukrainian film studios. For example, at least six German cinematographers worked for VUFKU, as German film equipment was considered the best at the time.

Dovzhenko did not receive any formal film-directing education in Ukraine. However, like his other colleagues, he was one of the Ukrainian intellectuals of the 1920s. He was associated with Semenko and the Futurists and was a member of Hart and VAPLITE, literary organizations in which Mykola Khvylovy, Mykola Kulish, and Maik Yohansen were members.

“The film society played the role of an educational institution at that time, and everyone learned through practice,” says Oleksandr Teliuk. “There were other writers and playwrights here, including experienced masters. However, in this sense, Dovzhenko was still unique. He received a better education than most of his colleagues in the industry: he had the experience of private study in Germany. Dovzhenko’s work was influenced by both his foreign education and a whole range of other experiences. Especially by his connection to the Futurists and the VAPLITE.”

Venice Film Festival poster, 1932

The VUFKU helped distribute Dovzhenko’s films abroad and arrange his lecture tours in Europe. The way Dovzhenko’s films were perceived at the time also depended on the Ukrainian film society. For example, Kinohazeta, which identified itself as a proletarian periodical, immediately began to criticize the director's films for being obscure for the masses and for portraying class struggle. Meanwhile, Kino magazine developed its own method of critical review based on the analysis of film language. At the same time, the majority of the review authors in Kino were biased in their own way: they themselves knew and supported the director. They regarded Dovzhenko’s films as the work of an entire generation and wanted to represent Ukrainian cinema.

After the VUFKU was suppressed in 1933, artists associated with Ukrainian cinema were harassed: Ivan Kavaleridze was banned from making historical films, Mykola Bazhan was accused of terrorist activities, and Les Kurbas was arrested and executed. Dovzhenko went to Moscow following Stalin's request and started filming commissioned films to avoid repression. The Soviet film critics would hardly mention Earth, and Dovzhenko would be referred to only as a director of communist ideology as if reinventing his portrayal. Dovzhenko’s connection with Mykola Khvylovy, Mykola Kulish, and other representatives of the “Executed Renaissance”, who were repressed as enemies of the state at the time, was silenced. As a result, this context of Dovzhenko’s work almost disappeared from Western film critics’ view.

Dovzhenko now: flaws and progress in the perception of the Ukrainian film avant-garde

Almost everyone in an independent Ukraine is familiar with Dovzhenko, yet again, mostly with his stereotypical image. Many works written in the last ten years continue to portray Dovzhenko outside the socio-cultural context of the 1920s or pay little attention to this connection.

One of the exceptions is Bohdan Nebesio’s The Silent Trilogy of Oleksandr Dovzhenko, one of the most fundamental works that redefines Dovzhenko's portrayal. In a brief biographical sketch in the first chapter, Nebesio shows those aspects of Dovzhenko’s life that were silenced by the Soviet authorities and that have rarely come to the attention of Western researchers. In particular, he dispels the myth of Dovzhenko’s impoverished family as well as presents facts that indicate the director's probable support for the Directory during the Ukrainian Revolution.

Bohdan Nebesio’s The Silent Trilogy of Oleksandr Dovzhenko

Nebesio notes the above-mentioned stereotypes about Dovzhenko. In order to dispel them, he emphasizes consistently that Dovzhenko’s connection with Ukrainian avant-garde groups formed him as a director. He also writes that Dovzhenko, in fact, studied on the film set, so the film society of the VUFKU directly influenced his style[29]. Nebesio also reveals the fact that Dovzhenko’s film language is deeply immersed in the context of European cinema of the time.

Although Bohdan Nebesio’s study shows that Dovzhenko's image is slowly being rethought in Ukrainian film circles, the director's relation to the socio-cultural context of the 1920s still remains a problematic one. For example, given today's image of Dovzhenko, paradoxically, one could say that he is far too famous: the figure of Dovzhenko "hides" the entire Ukrainian cinema of the early twentieth century. As Oleksandr Teliuk argues, Ukrainian film studies and cultural policy have sometimes gone too far in promoting Dovzhenko. Every year, texts are created that repeat roughly the same statements about his films, while the work of other VUFKU directors remains poorly researched.

It is not enough to simply know the important figures and events in Ukrainian culture. It is crucial to consider Oleksandr Dovzhenko, along with other representatives of the “Executed Renaissance,” in a more complex way, taking into account socio-cultural processes. After all, they were all part of a complex and ambiguous phenomenon – the Ukrainian avant-garde. Their works could contain Ukrainian themes and folklore motifs, and at the same time, they sought to embody their own ideas within the framework of the new socialist art. These ideas, however, had little in common with Stalin's socialist realism.

For this reason, it is necessary to create a complex vision of the Ukrainian film avant-garde, in particular, to promote the little-known works of directors such as Ivan Kavaleridze and Mykola Shpykovsky and to research the work methods of the Ukrainian film avant-garde cinematographers. There is already such research material available, and I hope that the more of it is shown, the sooner the mass perception of this period in the history of Ukrainian cinema will change. Furthermore, more people will no longer see the Ukrainian cinema of the 1920s as limited to the figure of Oleksandr Dovzhenko.

Footnotes

- ^ Небесьо Б. Німа кінотрилогія Олександра Довженка. Контекст. Київ: Національний центр Олександра Довженка, 2017. С. 39.

- ^ Перше десятиліття кінематографічної творчості Олександра Довженка / упор. В. Н. Мисливський. Харків, 2019. С. 107-111.

- ^ ibid. p. 130-133

- ^ ibid. p. 195-196

- ^ ibid. p. 116-120

- ^ ibid. p. 107

- ^ ibid. p. 157-162

- ^ ibid. p. 176-178

- ^ ibid. p. 195-196

- ^ ibid. p. 199-200

- ^ ibid. p. 241-242

- ^ Khvylovy himself started this discussion by calling to focus on European rather than Russian literature. The literary debate quickly turned into an ideological one, and the Soviet authorities began to persecute all those who agreed with Khvylovy.

- ^ Перше десятиліття кінематографічної творчості Олександра Довженка / упор. В. Н. Мисливський. Харків, 2019. С. 275-294

- ^ ibid. p. 298-300

- ^ ibid. p. 295-296

- ^ ibid. p. 309-319

- ^ ibid. p. 324-327

- ^ ibid. p. 362-365

- ^ ibid. p. 365-369

- ^ ibid. p. 179-180

- ^ ibid. p. 141-144

- ^ Rotha P. Celluloid: the film to-day. Longman, green and Co.: London, 1931. P. 135-154.

- ^ Sadoul G. Histoire d’un art: Le cinema. Flamamarion: Paris, 1949. P. 170-184.

- ^ VAPLITE – Free Academy of Proletarian Literature. It was a literary union in Kharkiv, which existed between 1926 and 1928. Mykola Khvylovy was one of its leaders.

- ^ The revolutionary years are the least studied period in Dovzhenko's life. It could be said for sure that at that time, Dovzhenko was a Borotbist, not a Bolshevik. As Bohdan Nebesio, a Ukrainian film and culture researcher, demonstrates, he also probably belonged to the army of the Ukrainian People's Republic.

- ^ Liber G. Alexander Dovzhenko: a Life in Soviet Film. London: British Film Institute, 2002. 309 p.

- ^ Rosenbaum J. Life and Death. Landscapes of the Soul: The cinema of Alexander Dovzhenko. URL: https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/2022/09/death-and-life/ (дата звернення: 10.09.2023).

- ^ Fujiwara C. Neglected Giant: Alexander Dovzhenko at the MFA. URL: https://bostonphoenix.com/boston/movies/documents/02557255.htm (дата звернення: 12.09. 2023).

- ^ Небесьо Б. Німа кінотрилогія Олександра Довженка. Контекст. Київ: Національний центр Олександра Довженка, 2017. С. 19-75.

Author: Anna Tsymbal

Translation: Anna-Maria Kotliarova

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva