Since the start of russia’s full-scale invasion, the number of maternity hospitals in Ukraine has significantly declined. While a one-third drop in birth rates during wartime is understandable, the mass closure of maternity hospitals across the country is far less easy to justify. These closures appear almost organic—an inevitable process of “natural” decline. In reality, however, their disappearance is largely driven by the current healthcare financing model and by unexpected standards introduced annually by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine.

Under Ukrainian law, state funding is available only to those maternity hospitals that handle a minimum number of births per year, as set by the Ministry of Health. At the start of the full-scale war, the ministry temporarily lowered this threshold: in January 2022, hospitals needed to register at least 75 births per six months; by 2023, the requirement dropped to 38. But in 2024, the bar rose sharply to 85, and in 2025 it is set to reach 100 births within the same period1 Response of the Ministry of Health to a request for public information.

. As a result, to retain public funding, maternity hospitals must now deliver more babies than they did before the war. This policy has already led to a 25% reduction in the number of maternity hospitals across Ukraine2 Data from the National Health Service of Ukraine (NHSU), 2021–2024, on recipients of the “Medical Care During Childbirth” package.

. Those that remain open are forced to cut costs, worsening working conditions for medical staff.

The example of maternity hospitals reflects a broader logic behind Ukraine’s ongoing healthcare reform—an approach built on the principle that “money follows the patient.” This consumer-driven view of medicine, combined with the undervaluing of caregiving labour, has produced complex and often troubling consequences.

In this article, we explore whether state funding should indeed depend on the number of births a facility handles, whether Ukraine truly needs as many maternity hospitals as before, and how the current system affects working conditions for healthcare professionals. We’ll also raise a broader question: how can the effectiveness of a healthcare system be measured in a way that supports its sustainable development?

Why Funding Depends on the Number of Births

Historically, Ukraine’s healthcare system relied on a network of specialised facilities—maternity hospitals. As of 2020, there were 46 such institutions nationwide. This system took shape in the Soviet era as part of efforts to combat high maternal and infant mortality rates that persisted until the 1960s. A vast infrastructure was built: women’s consultation centres, maternity hospitals, maternal and child health services, and rural birthing points staffed by midwives and feldshers. In subsequent decades, as medicine advanced and cities expanded, the situation improved, but the specialised “maternal” infrastructure remained, surviving stagnation, perestroika, and the economic shocks of the 1990s. A new stage of modernisation began in the 2000s, when—with support from international donors—some maternity hospitals were upgraded into perinatal centres equipped with modern technology, HIV treatment capabilities, and initiatives promoting partner-assisted births and breastfeeding. However, such improvements were selective and concentrated mostly in large cities.

The healthcare reform launched in 2016–2017 challenged the Soviet model and embraced Western models of healthcare systems—particularly their neoliberal approaches of recent decades, which promote the consolidation of medical institutions and the closure of smaller facilities in less populated areas. Under this logic, standalone maternity hospitals are seen as inefficient; they should instead be integrated into large multidisciplinary hospitals.

As a result, the closure of maternity hospitals began alongside the reform—and the process accelerated dramatically during the war. The National Health Service of Ukraine (NHSU), the body responsible for allocating state healthcare funds, calls this approach “selective contracting.” The mechanism behind this selection is precisely the link between funding and the number of births. Given current trends, these thresholds are expected to rise further, leading to the continued shutdown of smaller facilities.

Here’s how the system works. The state reimburses a hospital 15,137 hryvnias (about $360) per birth—whether it’s a natural delivery or a cesarean section3 The lack of differentiation in compensation rates is due to negative experiences in other countries, where higher fees for cesarean sections encouraged unnecessary procedures.

. This sum is relatively low, especially compared to private clinics in Kyiv, where prices are four to five times higher for standard deliveries, and up to ten times higher for planned cesareans. As the number of births declines, so do hospitals’ revenues. Meanwhile, any institution that fails to meet the Ministry of Health’s minimum requirement not only receives less funding but can lose the right to any public reimbursement in this category altogether.

If a maternity hospital fails to meet the required number of births, it loses eligibility for the “Medical Care During Childbirth” funding package the following year. For such a facility, this effectively means the loss of its main source of income—and, in most cases, closure. Maternity wards within large hospitals can continue to operate only because they are subsidised through other funding streams. Overall, the number of medical institutions receiving compensation from the NHSU for childbirth services fell from 346 at the end of 2022 to 259 in 2024—a drop of 87 facilities.

When setting the minimum threshold for births, the Ministry of Health and the NHSU justify it not only as a way to “optimise” the healthcare network but also as a guarantee of quality. Their logic is that only facilities that handle deliveries regularly have the practical experience needed to provide qualified assistance to mothers and newborns4 Order of the Ministry of Health No. 31.10.2011 “On improving the organisation of medical care for mothers and newborns in perinatal centers.” Also discussed in the course “Women’s and Children’s Healthcare” at NAUKMA in 2021 by pediatrician and former head of the NHSU, Andriy Vilensky.

. Staff in such hospitals are more likely to recognise, for instance, early signs of postpartum hemorrhage or critical conditions in newborns—skills that may deteriorate when deliveries occur infrequently.

Assuming that the reduction in maternity hospitals and wards truly aims to protect women’s and children’s health, rather than simply to save public funds, several contradictions arise.

One key question is how the “optimal” number of births is determined—the figure that supposedly ensures patient safety. Since 2022, the minimum standard has risen from 75 to 100 births per six months. But what data informed this decision? Who sits on the expert committees that establish these benchmarks? Ideally, such standards should be based on broad professional consensus among doctors and other healthcare workers. However, according to the NGO Medical Movement “Be Like Us”, the proposed introduction of medical self-governance raises concerns. Under the current legislative draft, self-governing medical bodies would have the authority to revoke doctors’ licences—potentially turning these institutions into tools of pressure against medical professionals, including union activists.

Another fundamental issue: is a low number of births really such an insurmountable problem? There are other possible solutions—organisationally more complex in some ways, yet simpler in others—than merely consolidating medical institutions. For example, regular staff rotation, training exchanges, and continuous professional development could help maintain expertise. Such ongoing education is already a legal requirement for healthcare workers—so why not implement it in this format?

Perhaps the most alarming question concerns safety itself—and the lack of real accountability mechanisms. The NHSU can withdraw funding for maternity or other care packages, but it has no authority to shut down hospitals. If local authorities choose to keep a facility open and finance it independently, the NHSU’s only response is to “explain to women that giving birth there is unsafe.” Last year, childbirths took place without NHSU contracts in at least four regions: Prykarpattia, Zhytomyr, Lviv, and Kyiv oblasts.

In practice, this means that hospitals with alternative funding sources and strong local government support can continue to deliver babies. Those without such backing—like in Vinnytsia and Zaporizhzhia—are being shut down. In the case of Zaporizhzhia, the closure also violates the law, since the reorganisation of medical institutions in frontline regions is prohibited until martial law is lifted. When local authorities do choose to keep maternity hospitals open, each such decision deserves individual scrutiny. Is it a matter of corruption and cynical profiteering at the expense of mothers’ and infants’ safety—or a genuine act of community resistance, a belief that the facility is worth saving?

This raises another question: is the idea of large, consolidated hospitals really the only path to quality medical care? It’s true that smaller maternity hospitals in rural areas often lacked adequate equipment, which inevitably affected the quality of services. One woman, for example, recalled giving birth to her first child in 2006 in the small town of Pryluky, Chernihiv region. Her labour was extremely difficult, and only later did doctors determine the cause—a short umbilical cord. The hospital, she said, had no ultrasound machine that could have detected the issue in advance. Comparing that experience with her next childbirth in Kyiv, she described the difference as “like night and day.”

Yet the problem lies not only in the size of the institution. The Ukrainian state has never funded its healthcare system even at the minimal level recommended by the World Health Organization. Resources have always been unevenly distributed. Unsurprisingly, hospitals in larger cities—with better local budgets, donor support, or substantial “off-the-books” income—show stronger performance indicators. The current healthcare reform only entrenches and deepens this inequality—a situation driven less by patient choice or staff competence than by chronic underfunding. A “European” approach without “European” levels of investment will mean that the “luxury” of giving birth close to home, in humane conditions rather than under a conveyor-belt system, will be available only to those who can afford private clinics. Others may face outright sabotage of the National Health Service’s plans. In fact, this is already happening.

Does Ukraine No Longer Need So Many Maternity Hospitals?

Since russia’s full-scale invasion, about six million Ukrainians have left the country, including roughly one-third of all women aged 18 to 59. The longer the war lasts, the less likely these women are to return—especially younger ones. The number of births has fallen by a third during the war. Ukraine’s fertility rate, which was already low before 2022, now stands at 0.8–0.9, among the lowest in the world (the replacement level being 2.1–2.2). The rapid reduction in maternity hospitals, then, likely reflects demographic forecasts that see little prospect of recovery in the near future.

At the same time, Ukraine has adopted a Demographic Development Strategy through 2040, whose main goal is to encourage higher birth rates. Alongside state support for families and better conditions for combining parenthood with employment, the strategy calls for improvements in healthcare quality and reproductive health. As the analytical outlet Texty notes, “the children born in the early 2010s can be seen” as a ray of hope. That generation, born during a brief baby boom, largely remains in Ukraine today, and by the time they reach reproductive age, “the security situation may improve significantly.” Despite current pessimistic forecasts, there is therefore a chance that Ukraine could see a rise in birth rates over the next decade.

Yevhen Averchenko, head of a maternity ward in Zaporizhzhia, recalls that such demographic shifts are not new in Ukraine’s history:

“In 1991, there was a drop in birth rates, and then suddenly the girls started having babies again. I remember in 2007, I delivered 25 births in a single day,” he said.

A doctor whose hospital also underwent reorganisation emphasises that maternity staff train throughout their entire careers. “These closures,” he says, “are destroying a highly qualified workforce.”

Because work in delivery wards requires a specific set of manual skills, quick reflexes, and readiness for emergencies, staff with such experience are highly sought after in other “high-intensity” hospital departments. According to gynecologist Iryna Stakhova from the town of Derazhnia in Khmelnytskyi region—where the maternity ward was shut down last year—many of their young nurses quickly found new jobs.

“The girls from our maternity unit became anesthetic nurses, surgical nurses, procedural nurses. They can easily handle that kind of work. A nurse from a therapy ward would never move to intensive care or surgery—but our girls did,” Stakhova explains.

This raises a crucial question: if birth rates rise again in the coming years, will maternity hospitals have enough qualified staff left? Many of these professionals may by then have retrained for other specialties—or left medicine altogether.

Consequences for Staff and Patients

One of the defining features of Ukraine’s post-reform healthcare system is its consumerisation—the idea that patients are now “clients” who bring funding with them, and that hospitals must compete for their attention. Yet medicine, like policing or emergency response, is a vital public service. The notion of competition over who catches criminals or puts out fires sounds absurd, even dystopian—yet somehow it feels acceptable when applied to healthcare. Such an approach could perhaps be justified if it clearly reduced mortality rates. But because the main wave of healthcare reform in Ukraine coincided first with the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and then with the full-scale war, it is almost impossible to make fair comparisons. For instance, the average age of death for men has fallen from 67 years before the war to just 57 today—a decline driven largely by combat losses rather than by deteriorating medical care.

Still, there are other ways to assess the reform’s effectiveness. If we accept that the quality of medical care depends not only on equipment but also on people—on how well teams work together, how rested and motivated the staff are, and how stable and fair their working conditions remain—then the reform’s impact looks deeply troubling. Already, there are growing signs that public hospitals may face an acute shortage of personnel in the coming years.

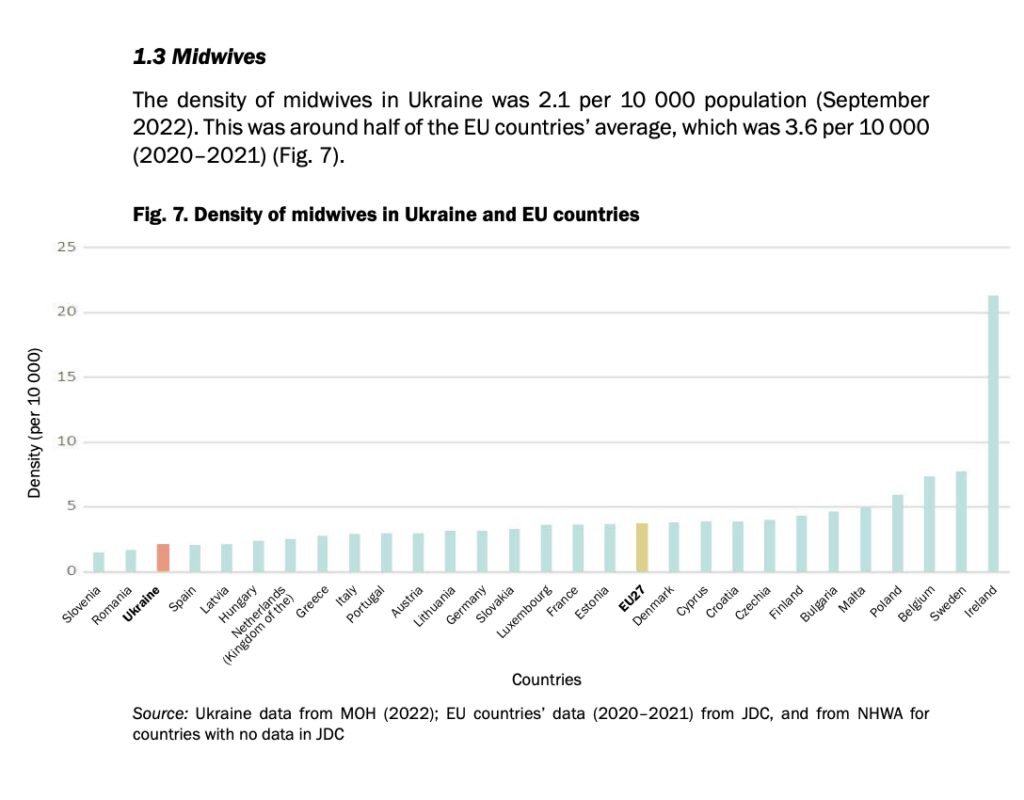

One might even make a wry observation: if patients are now “clients,” then by the logic of customer service, the number of service staff should be increasing. In reality, the opposite is true. Although Ukraine still has roughly the same number of doctors per capita as the EU average, it lags far behind in nurses and midwives.

Over the past 15 years, the number of mid-level medical workers—nurses, midwives, lab technicians, radiologists—has almost halved. A study titled “One for Three: How Ukrainian Nurses Work” found that one key reason was the deregulation of nursing labour introduced during healthcare reform. This led to extreme workloads without fair pay. When funding becomes tight, hospitals can now legally downsize mid- and junior-level staff and shift their responsibilities to those who remain. That is exactly what happened in many maternity hospitals after their budgets were cut.

A midwife from a frontline city, one of the participants in the “One for Three” study, shared her story. When russia launched its full-scale invasion, she stayed at her hospital and agreed to take on more duties because there weren’t enough staff.

“They asked me to serve as senior nurse in two departments at once—even though my maternity ward was already the largest in the hospital. But I agreed. I never refused. I helped everyone, always,” she recalled.

Eventually, she was working 11–12 hours a day, almost without vacation. At first, she received overtime pay, but as funding shrank, the bonuses disappeared. The hospital administration then began mass layoffs and encouraged senior nurses to write formal reports on their colleagues to justify dismissals. The midwife refused to take part. This led to conflict with management, deepening her burnout and frustration over low pay. She eventually quit, saying she felt “like a sick, depressed person.” Today, she works as a midwife in a multidisciplinary hospital in the same city, where a small maternity ward still operates—kept alive only through cross-funding from more lucrative state packages, such as those for stroke treatment or infectious disease care.

In the town of Derazhnia, Khmelnytskyi region, Iryna Stakhova, head of the gynecology department, described a similar story. Their hospital lost the right to provide maternity care after its neonatologist went on maternity leave and management failed to find a replacement in time. This happened despite the fact that the hospital had met the Ministry’s delivery quotas even after they were raised. Stakhova calls it an example of administrative negligence. The staff have since taken legal action against the hospital’s administration. An active trade union has been trying to resist the director’s decisions, which employees believe reflect a lack of interest in developing the facility. But the “battle” for the maternity ward has been lost. Now, the hospital offers only outpatient women’s consultations. If a woman goes into labour or develops complications, she must travel 40 kilometers to Khmelnytskyi—except in emergency cases. According to Stakhova, this will likely make safe childbirth inaccessible for the most vulnerable women, especially those from rural areas.

“The women are heartbroken,” Stakhova says. “They come to us, bringing their discharge papers. They tell us, ‘No one even came up to me, no one examined me. It was like a conveyor belt.’”

Not every woman is willing to give birth far from home—especially in such a vulnerable state, and without the support of loved ones. In 2018, more than half of all births in Ukraine were partner-assisted, and in some hospitals today, almost all deliveries take place this way. Research shows that the presence of a trusted person has a positive effect on both the mother and the newborn. The growing popularity of partner births is therefore a welcome trend—and even a relief for the medical staff. Partner deliveries are also included in the free state package “Medical Care During Childbirth,” funded by the NHSU. Yet when a woman must travel far to give birth, not every family can afford for a partner to accompany her—especially if it means paying for lodging.

One of the hypotheses of the “One for Three” study was that overworked nurses might delegate some caregiving duties to patients’ relatives. But most nurses did not see relatives’ presence as helpful—except for those working in maternity wards, who spoke favourably about partner births.

“When we have family rooms, it’s really good. We talk with the fathers—they support us, they help us. Usually the men help. The grandmothers, they’re a bit jumpy, nervous about everything, but the dads—they’re adequate. The young people now are very educated, modern,” says a near-retirement nurse from a district hospital.

Despite her own maternity ward losing state funding, Iryna chose to stay in the Derazhnia hospital. She has worked there for most of her life and, together with the local trade union, continues to fight for its survival. Some of her colleagues, however, managed to find new jobs in Khmelnytskyi. For medical workers living in or near large cities, transitioning to “viable” hospitals is relatively realistic. But when distances reach hundreds of kilometers, the move becomes far more difficult—especially for older staff.

The “One for Three” report describes the case of a near-retirement nurse from a large district centre located far from any major city. As birth rates fell, her maternity hospital suffered from chronic underfunding. To cut costs, management reduced both staff numbers and wages. Today, she earns the equivalent of 6,700 UAH (around $160) per month and must single-handedly care for newborns and mothers across three floors. This poses serious risks for patients whose condition may deteriorate suddenly and unpredictably.

“We have to leave the women our work phone numbers because we can’t be on the same floor. These are newborn babies… I just don’t understand the administration that allowed this, because God forbid something happens—a bad, ugly situation—and the nurse just doesn’t make it in time, from the fifth floor to the first or the other way around,” she said.

According to her, staffing levels are so low that she is sometimes assigned to the neonatal intensive care unit, where at least two nurses per shift are required by regulation. In practice, only one is usually on duty. But the job requires specialised training, which she does not have. Another nurse from a neonatal intensive care unit in a regional hospital described the same reality:

“With this war and these wages, we now work one per shift. But in this department, that’s not even allowed […]. Because it’s such a heavy ward—anything can change at any moment,” she said.

This shows that even so-called “viable” hospitals are struggling with staff shortages. Many healthcare workers from the closed maternity wards are unwilling or unable to relocate, as commuting to another city demands both time and money. The average nurse’s salary, after all deductions, is only 10,800 UAH—roughly $260 per month.

But most importantly, these stories demonstrate that staff cuts directly endanger the lives and health of patients. One likely reason for such violations is the chronic undervaluation of nurses’ work. The NHSU strictly monitors hospitals’ compliance with doctor qualifications and equipment standards, yet barely regulates the number or skill level of nurses. Nor does it monitor their workloads, which often lead to burnout and a steady decline in the workforce. Yet childbirth is not only about doctors and equipment—about technical safety—but also about the emotional and psychological sense of safety that medical institutions create for mothers. That sense of reassurance is often provided by nurses.

A glimmer of hope

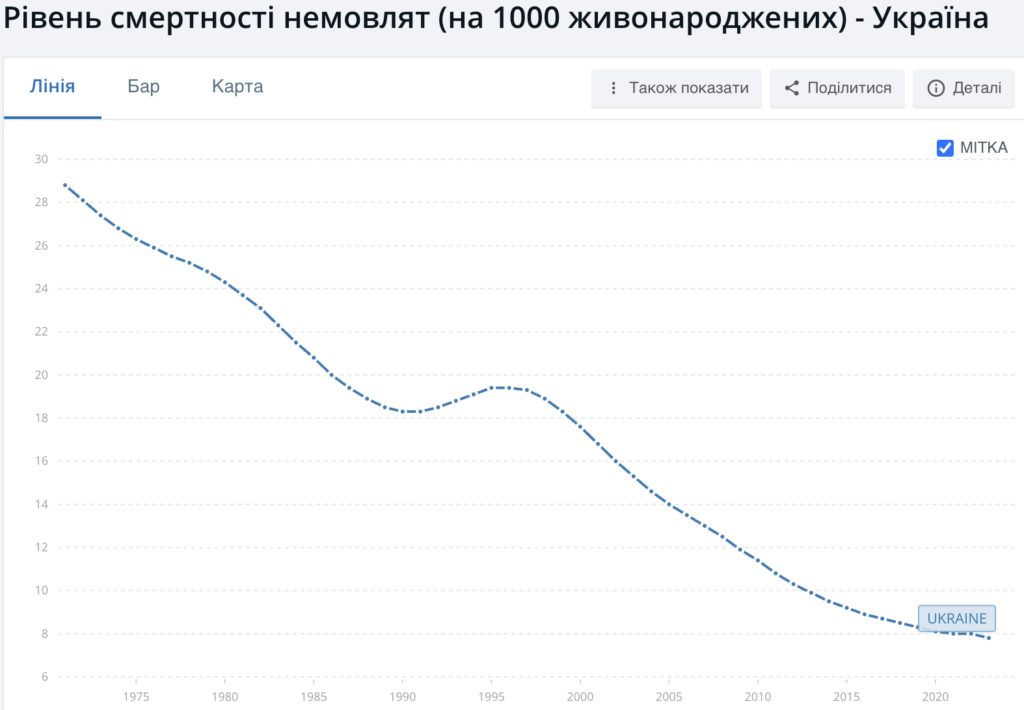

Despite the full-scale war, maternal and infant mortality rates—at least in territories under Ukrainian control—have not worsened. Maternal mortality rose sharply in 2021 (26 deaths per 100,000 live births), likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2023, this figure fell to 15 per 100,000, which is still three times higher than the EU average but on par with Portugal and lower than Latvia. At the same time, it represents the best maternal mortality rate ever recorded in Ukraine. The same applies to neonatal mortality: fortunately, there was no deterioration during the pandemic, and the current rate of 7.8 per 1,000 live births, while worse than the EU average, is the lowest ever documented in Ukraine.

These data, however, reflect the situation in 2023, when the Ministry of Health temporarily lowered the minimum birth threshold, allowing many maternity hospitals to keep operating. This flexibility freed up resources to help those who dared to bring new life into the world amid war. In the following years, as the thresholds rose again, the number of maternity hospitals began to decline. The impact on patients remains uncertain—according to acting head of the Department of Medical Services, Yevhen Honchar, reports for 2024 are still “under review.” For medical staff, however, the effects are already clear—and mostly negative. This raises a pressing question: what future lies ahead for Ukraine’s maternity care?

In the end, the situation in maternity hospitals during the war reflects broader healthcare reform—a system focused on consumerisation and economic efficiency, yet largely blind to the social and human aspects of medical care.

The appeal to “protecting patients’ interests” raises a series of questions. How exactly is the “optimal” number of births per facility determined? Why does closure remain the only available solution—rather than staff rotation or training? And if this is truly a matter of life and death, why do the Ministry of Health and the National Health Service of Ukraine have no real tools to intervene in hospitals that continue to deliver babies without an official funding “package”?

The “money follows the patient” model—and the accompanying rhetoric of competition among hospitals—appears deeply flawed, if only because even the best “service” in a maternity ward will not convince women to have more children. Healthcare institutions are not businesses, and the number of their “clients,” at least in the case of childbirth, does not depend on successful marketing. Instead, this model reinforces spatial inequality: hospitals in larger cities, which already had greater resources, once again gain advantages—both in funding and in patients. Treating patients as clients also strengthens private medicine, which can now access public funds but remains affordable only to a small fraction of Ukrainians.

Meanwhile, unstable and unpredictable working conditions—and a weak tradition of collective action—are pushing many medical workers, especially nurses, out of the profession. While the war and pandemic have made it difficult to assess the overall effectiveness of Ukraine’s healthcare system, there is abundant global evidence that no health system can function without sufficient nursing staff5 DOI references:

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1717

https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000233

https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_972_22

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znae215

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00768-6

https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001519.

Neglecting the importance of care work, chasing financial metrics, and leaving patients defenseless against institutional misconduct—these have become defining traits of Ukraine’s healthcare system in recent years. In maternity care, these problems are especially visible—and especially alarming.

And yet, there are reasons for cautious optimism. Hope emerges in the growing activism of the Medical Movement “Be Like Us”, in the resilience of trade unions and patient organisations, and in the first discussions around the idea of a medical ombudsman. Ukrainian society and professional communities are beginning to articulate new demands—for stability, compassion, and accountability in the state’s approach to healthcare.