In April 2000, Oleg Dubrovsky managed to sign on at the Dnepropetrovsk Rolled Products Works or DZPV (Днепропетровский завод прокатных валков). A month earlier he had quit his job at Dneprotyazhbummash before they could sack him for shop-floor organising; another two years before that he had instigated a protest strike over unpaid wages at the nearby precision pipe works, where he was also dismissed and blacklisted.

At the age of 45, Dubrovsky, who had worked previously as a rolling-mill operator and boiler-house maintenance fitter, had to learn a brand-new profession: metal pourer in the foundry, coaxing still-molten steel into a machine that cast it into balls. When the machine was down, he filled in with the physically demanding tasks of a castings dresser, cutting and manoeuvring the still red-hot steel castings, and a ditcher “whose basic tools were the shovel, crowbar and sledgehammer” (pages 53-54).

In the “flames, dust, smoke and din” of the smoke-blackened foundry with its leaking roof, Dubrovsky got talking with his new colleagues and asked them what they knew of its history. Having rebelled against Brezhnev-era discipline in the 1970s, been inspired by Polish Solidarnosc, and gorged on anarcho-syndicalist and Trotskyist literature as it became available prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, he had for many years read everything he could lay his hands on about the past of the local workers’ movement.

DZPV began in 1896 as Sirius, a machine builder, and in 1913 shifted to rolling steel products. During the 1905 revolution, the factory director had been “killed by anarchists for his cruelty towards workers”, which had opened a “heroic saga of anarchist revolutionary terror” in Yekaterinoslav, which was renamed Dnepropetrovsk in 1926 and renamed Dnipro in 2016. But Dubrovsky’s new colleagues knew nothing of this drama, or even of the revolutionary convulsions of 1917-21, he found. Some of them knew the factory had been occupied by the German army between September 1941 and October 1943, but not of the fate of its workers when the Soviet army retook Dnepropetrovsk.

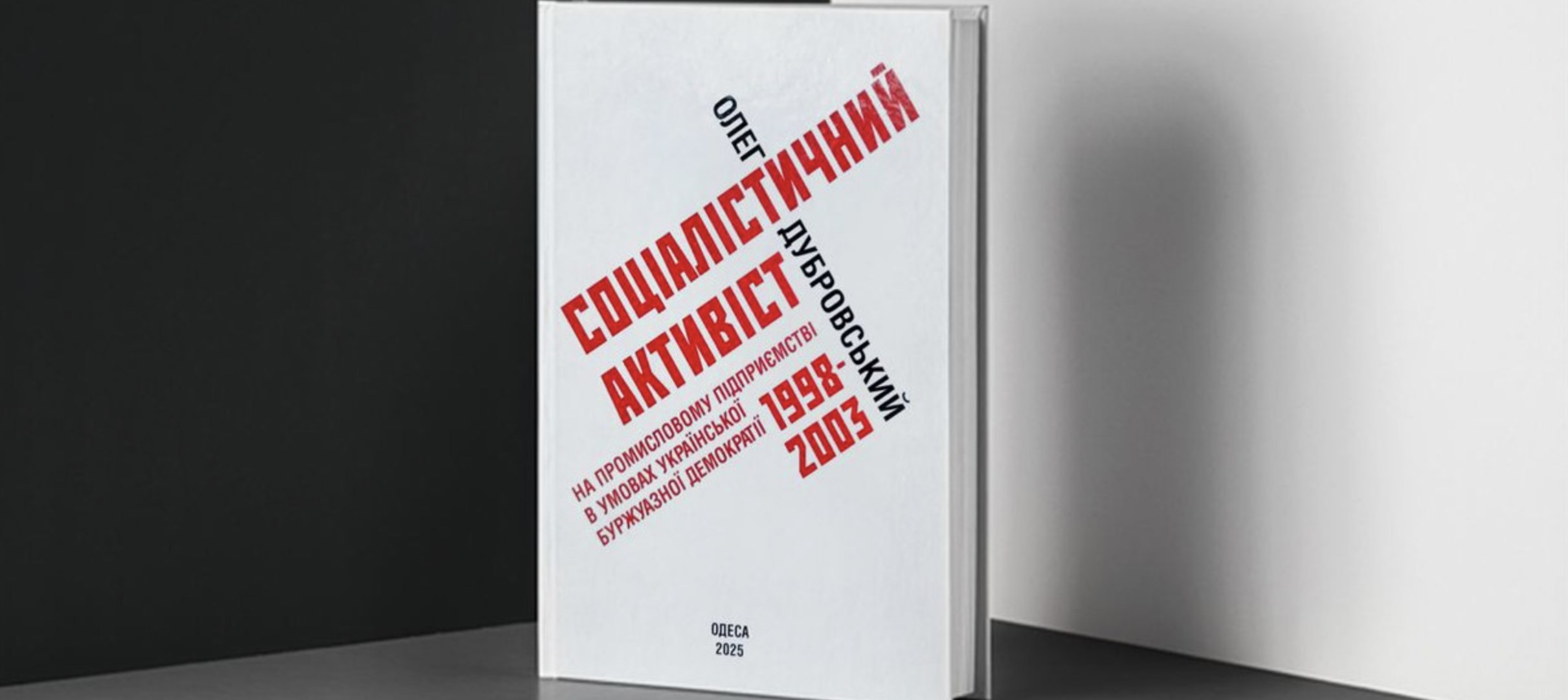

Cover of Oleg Dubrovsky's book A socialist activist in industrial workplaces under Ukrainian bourgeois democracy 1998-2003

No legends, no memories, remained; no knowledge of the revolutionary events or the Sirius workers’ participation in them, of the formation of trade union organisations and a factory committee, of the factory Red Guards and [food] procurement brigades. No-one was interested in the factory museum, whose doors were closed, and nobody demanded that they be opened.

The example of the DZPV convinced me, once again, that the revolutionary traditions of our proletariat were a myth, a soap bubble, that had been inflated by CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] propaganda solely with the aim of endowing the CPSU with some sort of right of revolutionary succession.

This didn’t mean, though, that the social memory of the DZPV workers was completely dead. It had preserved a loyalty, but a very different type of loyalty: to some sort of pre-revolutionary tough-but-fair paternal capitalist. The longing for a real boss, for a really “just” boss’s whip, could clearly be heard in this wage slaves’ loyalty.

This bitter conclusion, on the effect of the Soviet experience on the consciousness of the industrial workers it claimed to represent, runs through Dubrovsky’s unique and fascinating memoir, which recounts in detail a five-year stretch in his decades-long efforts to organise, and propagandise socialist ideas among, his fellow industrial workers.

This review is not by a neutral observer. I met Dubrovsky in Moscow in the early 1990s, visited Dnepropetrovsk as his guest in 1996, then published a pamphlet based on extended interview with him, and have been in touch with him[1] on and off since then. Living the relatively comfortable existence of a UK-based journalist and researcher, I shared (and share) his affinity with socialism and admire his conviction of the need both to do and to write.

The shadow of the USSR

Dubrovsky’s book, published this year in Odesa, is laced with his awareness of the disconnect between how workers actually lived, and the motive force of change that socialists of Dubrovsky’s generation – our generation – had often assumed, or hoped, them to be. He shows how the Soviet experience – the revolutionary transformations in the early 20th century, the nightmare of Stalinism, and the stifling, bureaucratic authoritarianism under which he began his political activity – cast a long shadow over post-Soviet Ukraine.

The “Communist” rulers perfected the art of emasculating and gutting all memories of collective working-class action. In the 1970s and early 1980s, protests came in short, isolated outbursts. Workers’ survival strategies could be by turns indifferent, individualist, cynical. As repression eased in the late 1980s, workplace organising reappeared[2] – but still, the numbing effect of Soviet “socialism” left Dnepropetrovsk’s industrial workers ill-prepared for the onslaught on living standards and workplace conditions that followed the transition to independent Ukraine in 1991.

Oleg Dubrovsky

Self-serving managers adapted to the “wild east” markets of the 1990s and trade union bureaucrats found new depths of servility: Dubrovsky was perpetually at war with them. But he worked to understand not only the external enemies of the industrial working class, but also the internal damage done to it.

In the DZPV foundry, he writes, it would be no exaggeration to say that the workers were “completely apolitical” (page 56). They had no interest in the “Gongadze affair” (the scandal caused by a journalist’s murder by police in late 2000) or the “Ukraine without Kuchma” movement directed against the president. Such “indifference to bourgeois politics” might have had a positive side if workers sought a political alternative, but they didn’t, Dubrovsky writes. The ideologies that came up in discussion in the foundry were authoritarianism (some workers said “a Stalin is needed” to restore order) and the purposes of Christian orthodox religion.

Much more vigorous debates raged about how best to make use of the garden plots, that stretched geographically right up to the factory gates, and on which many Dnepropetrovsk workers depended for food supplies and income. (Dubrovsky describes the luxurious plot, with 57 chickens (!) and an orchard with 40 fruit trees, owned by one of the city’s “former people” – party officials who converted minor Soviet privileges into material wealth in the 1990s (page 73.))

Daily life in the workshop was also shaped by the consumption of alcohol (in context, most likely vodka) “practically every day” (page 57). Management did nothing to combat this “social evil”, “because workers who drink, sooner or later, succumb to various forms of informal dependence on that management”.

Another war that management did little to fight, and never won, was with theft – an “assault on bourgeois property” of a “systemic, solidary” character, in Dubrovsky’s eyes. Building materials such as firebricks and metal scrap were shipped out in quantities. Metal additives for steel alloys, e.g. nickel, chrome or molybdenum, were the most sought after. Workers converted these valuables into cash by selling them to informal networks of unlawful traders.

Workplace organising

Dubrovsky’s book covers his time at three workplaces: Dneprotyazhbummash, where he found work in 1998 soon after his dismissal from the Dnepropetrovsk Precision Pipe Works for organising a strike; the above-mentioned Dnepropetrovsk Rolled Products Works (DZPV), where he survived just nine months, from April 2000; and the precision pipe works (also called the Experimental Pipe Works), to which he returned in 2001.

At Dneprotyazhbummash, a machine building works with strong links to the timber and paper industries, Dubrovsky worked in the steam-power shop. The works suffered from the epidemic of late payment of wages that spread across most former Soviet countries in the 1990s. When Dubrovsky arrived, payments were a year behind. Most debts were paid off – surprise surprise – just before the 1999 presidential elections, at which the incumbent Leonid Kuchma, who started his political career in Dnepropetrovsk, successfully sought re-election.

Abandoned factory Dneprotyazhbummash. 2020

By January 2000, there were five months’ worth of wages outstanding (May to September 1999). Not a word of explanation from management; not a word of protest by the collaborationist “official” trade union. Four-fifths of the steam-power shop workers signed a letter, drafted by Dubrovsky, asking management for an explanation: they coughed up more money – but also singled him out as a troublemaker.

Far less successful than such shop-floor organising were Dubrovsky’s attempts to establish a library of socialist literature in the remains of the factory’s “red corner”, which had been used in the CPSU’s times for its propaganda. The library stock was repeatedly vandalised, and flyers informing workers of its existence torn down. He had hoped that the communist and anarchist literature in the library would win around his fellow workers to socialist ideas; “at the next stage, educational circles (above all, studying political economy) must be formed, which could then work outside the factory”. But none of this came to pass.

Dubrovsky recounts that this pattern – partial success on industrial issues, failure to convince his colleagues of socialist ideas – was repeated at DZPV and the precision pipe works. In his extended account of his activity at the precision pipe works between 2001 and 2003, he fills out more of the details: the dynamics between factory owners, a succession of managers with varying degrees of corruption, security personnel, old “official” trade unions and different sections of the workforce.

The crowning success of his trade-union organising was a three-week boycott of 12-hour working that he initiated there in October 2002: workers “successfully counterposed to the bosses’ arbitrary diktats their will, their class solidarity”, and re-imposed the 40 hour week (page 136).

The trade unions

Dubrovsky’s stubborn efforts to disrupt managers’ control over workforces make him uniquely well placed to explain the role of the old trade union structures, inherited largely unchanged from Soviet times and integrated closely into management. In some Ukrainian workplaces – for example, much of the coal industry – these unions had in the late 1980s and 1990s been challenged and even replaced by unions that were named “independent” and to various degrees were really independent. In these cases, the automatic deduction of union subscriptions from wages, for direct transfer to union bureaucrats, ended; membership once again became a relationship between workers and their own organisations.

But Dubrovsky conducted his independent organising activity often with the help of colleagues, but without successfully breaking the hold of the old unions’ membership structures.

In 1997-98, during the brief all-out strike at the precision pipe works, he had been chairman of the rank-and-file strike committee, which led to his victimisation and dismissal. In 2001, he returned to the works, regarded with some combination of respect and suspicion as the leader of an ultimately unsuccessful struggle. But in the intervening three years, labour conditions had deteriorated drastically.

The rolling mill operators, who comprised the main type of skilled labour in the factory, had worked for those three years without being paid. And they had without resistance surrendered the eight-hour day, and in 2001 were all working 12 hours per day in two shifts, 7.00am-7.00pm, and 7.00pm-7.00am.

Dubrovsky explains the trade union officials’ complicity in excruciating detail. Soon after his return to the works in April, a meeting of shop delegates was held to discuss the annual renewal of the collective agreement governing wages and conditions. One manager tore into a delegate who, following a conversation with Dubrovsky, dared to question the 12-hour shift (which would only be reduced to 8 hours after the boycott in October 2002, mentioned above); another manager, just before the new draft agreement was to be read out, leaped up to announce that part of the previous month’s pay was being paid out in the shops, causing many of the delegates to depart (page 95).

The official trade union representatives not only failed to question this farce, but allowed “voluntary” Saturday working, which had been scrapped in 1989-91 in the face of worker protest, to be reinstated (pages 111-112). When Dubrovsky tried simply to obtain a copy of the collective agreement for display in his shop, he ran into a wall of obfuscation (pages 113-114).

Dubrovsky witnessed two serious accidents, causing life-changing head and facial injuries, and describes how managers effectively bribed the victims not to enter a report. “In neither case did the ‘official’, formally-existent trade union put in an appearance, while the factory managers responsible for worker safety tried, as they always do, to put the responsibility for the accidents on the victims.”.

Discussion and conclusions

Dubrovsky concludes that his efforts at socialist propaganda failed almost completely, but his organising around wages, hours and workplace conditions had some success. His workmates at the precision pipe works were obsessed with the tabloid press – a striking contrast with the thirst for socialist and other political literature in 1989-91 – and had no more interest in the socialist books and newspapers he offered than workers at Dneprotyazhbummash had had. In the 2004 elections, support for Viktor Yanukovich, the president who would be overthrown by the Maidan uprising of 2013-14, was overwhelming, Dubrovsky writes. There were rumblings among workers about the need for punitive violence against the 2004 “Orange revolution” that challenged Yanukovich’s ballot-rigging.

Illustrative photo

Drawing up a balance sheet of his activism, Dubrovsky writes: “Given the current extremely low level of development of class consciousness among workers, and their alienation from socialist ideas, my trade-union activism seemed much more dangerous to the bosses than ‘ideological subversion’.” Actions such as the strike Dubrovsky organised in 1997, and the boycott of 12-hour working in 2002, had hit the company hard.

Further: “How to overcome the yawning gap between [industrial workers] and socialist ideas? How to infect them with the virus of class solidarity? How to draw their attention to their general class interests? My practice, described above, did not give answers to these questions.”

I want to say to Dubrovsky (and I expect that, thanks to the translators!, he is reading this) that this is not only about his practice. By bringing it to a wider audience, he has done a service to our generation and those that follow. But the problems on which he almost broke his teeth were very widely shared. A relevant example is a recent article by another old comrade of mine, Bob Myers, who, like Dubrovsky, spent decades as a committed, well-read socialist in industrial workplaces, in the very different political environment of the UK[3]. He wrote:

‘The Workers United will never be defeated!’ This slogan was chanted on the many mass demonstrations […]. And what a meaningless slogan it was. The working class had united behind the imprisoned dockers [in 1972], but when the miners went on strike for a year [1984-85] no-one struck in solidarity, despite massive sympathy. What had changed? We were all defeated. Maybe it wouldn’t be very catchy, but if only someone would chant ‘The workers have been defeated, let’s think why?’

Today, writes Myers, still hopeful despite the horrors of Gaza, Sudan, Ukraine, and the looming threat of climate change, he asks: “Can we find a way out of this terrible situation? I look back at my younger naivety that thought social transformation was within reach and relatively straightforward. Our ‘Party’ would lead the masses to power. Today things do not look so simple.”

For Dubrovsky, it is not “party”, but “socialist propaganda” that is the necessary instrument for changing the working class. My own view is that neither of these levers are sufficient. Our many attempts, collectively, to use both of them were weak, in part, because of the fragility of our understanding of the late 20th and early 21st century circumstances in which we made our efforts. We refused, quite rightly, to abandon the socialist principles we learned. But in many different ways we often collectively turned them into dogma, empty slogans that Myers compares to religion:

Collective attempts to understand the present? Ha! What we have on the ground is a multitude of little sects, who champion their tablets of stone in fierce competition with all the other tablets. The ‘debate’ more resembles the archaic quarrelling between different schools of theology than anything that might usefully contribute to a real understanding of where we are.

Dubrovsky is no less scathing than Myers about sections of the “left” in which we all worked, and excoriates “revolutionary radical fantasists” who “float in the geopolitical firmament” and look down their noses at workers’ day-to-day struggles, dismissing them as “economistic”.

These people forget that:

We need to deal with a new proletariat, which has not completed the process of its formation, has not yet broken all its ties with the countryside, which, in developing its consciousness of itself, has no revolutionary traditions, has nothing with which to connect with that class which, on the territory of the former Russian empire, at the beginning of the twentieth century, carried three revolutions on its shoulders. We need to start all over again from the beginning…

That we are talking about class formation is an important insight. But let us consider further how we understand that process. I think it will unfold in the 21st century in ways that have far less in common with the revolutions of the 20th century than Dubrovsky seems to assume.

Demonstration in Kyiv, March 1917

For a start, the working class we are dealing with will not look much like the one that spearheaded the 1917-21 revolutions – nor even, in my view, the important but narrow section of workers among which Dubrovsky has conducted his political work. Even in Ukraine at the time at which he was writing, ten years out from the collapse of the USSR, there had been huge changes outside the industrial workplaces. Millions of Ukrainians had begun to live as migrant workers in western Europe; millions more were employed in the service and IT sectors that had hardly existed in Soviet times. Ukraine, like most countries, has seen a huge expansion of precarious labour. And there are aspects of working-class experience, as real in Dnipro as anywhere else, that Dubrovsky barely touches on, in particular the domestic (reproductive) labour, mostly by women, that goes together with wage labour.

The chronological framework for Dubrovsky’s book (1998-2003) means that he does not address the sharp changes in working-class life, and consciousness, brought about by the initial Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014 and the all-out war since 2022. Dubrovsky participated in voluntary defence units based in Dnipro in 2014-21, and again in 2022-25, and from the outset argued for the need to unite to defeat Russian aggression[4]. In the article “How Not to Lose this War”, included in this book as an Appendix, he puts the case for widespread nationalisation, a state monopoly of foreign trade and state control over strategic sections of the economy as the best way for the (capitalist) Ukrainian state to defend itself.

I hope that in future, he will be able to tell us how labour and life has changed in Dnipro in wartime, and join the discussion about this among younger socialist activists in Ukraine, to which the recent book by Daria Saburova, Women Workers in the Resistance[5], is an important contribution. My point, for the purposes of this review, is that a fully-rounded understanding of working-class experience will include not only the industrial labour about which Dubrovsky writes so insightfully, but also the disruption and shocks brought about by war and migration, the changes in household (reproductive) labour, the consequences of “globalisation” and the transformation of economies beyond the factory gates, and so on.

Dubrovsky’s experience, and that of other militants, needs to be set in a wider context, not only in the sense that the working class is a demographically wider phenomenon, but in terms of our understanding of the working class as the motive force of social change. What does the “class formation”, to which Dubrovsky draws attention, mean today?

One thing that Dubrovsky is telling us, I think, is that the need to “start all over again from the beginning” is rooted in Stalinist nightmare and the whole Soviet experience, which so completely buried the changes brought about by the early 20th century revolutions in Russia, Ukraine and elsewhere in the former Russian empire. And we know from our experience of working-class movements in western Europe that the consequences of this are by no means limited to the former Soviet territories.

In my view it is worth going back to basics here, to consider what Karl Marx meant – writing at a time when at a time when the working class was demographically an insignificant minority – when he envisaged that “communist consciousness” would in future be produced “on a mass scale”. This would amount to “the alteration of men [sic] on a mass scale” – and that, in turn, could “only take place in a practical movement, a revolution”. In other words, changing minds and changing the world were one and the same process. For Marx, revolution was necessary “not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew”[6].

I think that the “starting all over again” that Dubrovsky advocates should not be seen narrowly. Propagandising socialist ideas is only one aspect of a much bigger, deeper, more complicated task. Bob Myers, addressing fundamentally the same questions, writes:

It would be idealistic to imagine that people from a culture subjugated by a hierarchical society for many thousands of years, who have been ousted from any meaningful control over the most basic human activity will somehow emerge overnight as rational, co-operative beings, like a butterfly from a chrysalis.

Here Myers is talking about the working class in the early 21st century doing what Marx called “ridding itself of the muck of ages”. Myers goes on:

If we are somehow lucky enough to avoid the total destruction of humanity it may take generations for truly co-operative people to develop. But humans lived as co-operative beings for hundreds of thousands of years and have experienced class divided oppression for only a few thousand. We are fundamentally a co-operative, social, caring species. Our brains, our language, our capabilities all became what they are today in co-operative relations. Class society briefly, hopefully, submerged this real human spirit into the selfish, inhuman world of slaves and slave owners, Kings and serfs, bosses and wage labour.

And:

[…] If we are agreed that the route out of human extinction lies in the advancement of true, international co-operation and production rationally organised to meet human needs, then even now in our political and social activities we need to try to begin to develop an ethos, a culture that points in the direction of that future. How in our modern times can we create the culture of the Greek City state, but with the slaves and women now leading the debate?

It is on this level, I think, that the selfless contribution of militants such as Dubrovsky can be understood. His battles with two-faced politicians, brutal managers and cynical trade union officials; his sensitive understanding of, and oftentimes frustration with, his colleagues; his difficulties in stirring interest in his deeply-held socialist convictions – all this is best seen in the context of the crisis that drives 21st century capitalism to find new ways to degrade, dehumanise and alienate workers, the overwhelming majority of human beings who depend on the sale of labour power for their livelihoods. The Russian war on Ukraine is one of the ultimate, destructive manifestations of capitalism’s crisis.

For socialism to mean anything in these times, it has to imagine and inspire a complete remaking of society, a complete remaking of us as people. I do not have any easy formulae as to how this will happen, or how it plays out in practice, but I hope that – despite war and the geography that separates us – we will continue discussion of it. Dubrovsky’s book is an essential contribution to that.

Simon Pirani, May 2025

Footnotes

- ^ Oleg Dubrovskii with Simon Pirani, Fighting Back in Ukraine: a worker who took on the bureaucrats and bosses (Index Books, 1997). Available as a pdf here.

- ^ Dubrovsky has compiled a document collection (unpublished) about this period: Demokratizatsiia I glasnost’ ot KPSS na promyshlennyom predpriatii 1986-1990. Sbornik dokumentov.

- ^ Bob Myers, “From Anaximander to Marx, or how I spent half my life in a ‘revolutionary’ cult and the other half working out why”, April 2025.

- ^ Dubrovsky’s wartime activity is described in the presentation of his book on the Proletar Ukrainy web site, and his wider view of the war set out e.g. in his article “Ukrainski sotsialysti natsional’no-vizvol’na borot’ba” (June 2024).

- ^ The book is published in French. Daria Saburova, Travailleuses de la résistance. Les classes populaires ukrainiennes face à la guerre (Editions de Croquant, 2024). See also an interview with Daria and Denys Gorbach here.

- ^ Karl Marx, The German Ideology, chapter 1 on “Feuerbach: opposition of the materialist and idealist outlook”. See here.

Author: Simon Pirani

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva