“For the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals, from the moment of conception until death”, wrote biologist and writer Rachel Carson in her influential 1962 book Silent Spring. She noted, “In the less than two decades of their use, the synthetic pesticides have been so thoroughly distributed throughout the animate and inanimate world that they occur virtually everywhere”.

Despite the geographical and temporal distance between the United States of 1962 and Ukraine of 2025, Carson’s work is far more relevant to us than it may seem at first glance. Today, Ukrainian agriculture is inextricably linked to the use of large quantities of toxic chemicals, or pesticides. This article is an invitationto look beyond the yellow horizon of sunflower fields and consider the price Ukraine pays, despite the war, to continue fulfilling its role as Europe’s ‘breadbasket.’

Agrochemical (In)Security

The role of pesticides in agricultural production is clear: they are meant to protect crops from potential ‘attackers’, such as other plants, insects or fungi that could destroy them. The ambiguity arises when society, represented by an authorized state body, must determine whether the benefits of using a particular pesticide outweigh the risks to human health and the environment. One way to get closer to the answer is to look at the ratio of relatively safe to hazardous pesticides, based on data from the State Statistics Service.

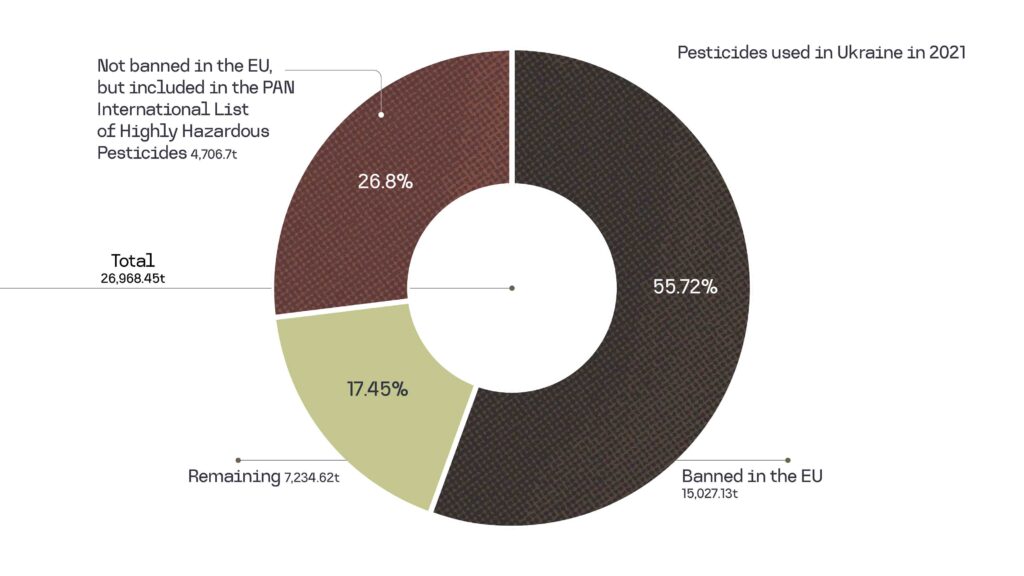

Thus, more than half of all pesticides used in Ukraine consist of chemical compounds that are banned1 Despite the ban, companies may continue to use certain pesticides if they obtain a special permit. In other words, a ban does not mean that they will be completely withdrawn from circulation, but it does simnifically restrict their use.

in the EU (see Infographic 1). This means that every second kilogram of pesticides used to treat Ukrainian fields contains dangerous substances that the European Union has rejected. Nevertheless, the remaining pesticides are not entirely safe either: dozens of these products are included in the International List of Highly Hazardous Pesticides, maintained by the Pesticides Action Network since 2009. A compound is included in this list if it causes ‘high incidence of severe or irreversible adverse effects on human health or the environment’. To understand what exactly justifies such risks, it is worth examining which chemicals are most common and what they are used for.

Infographic 1.

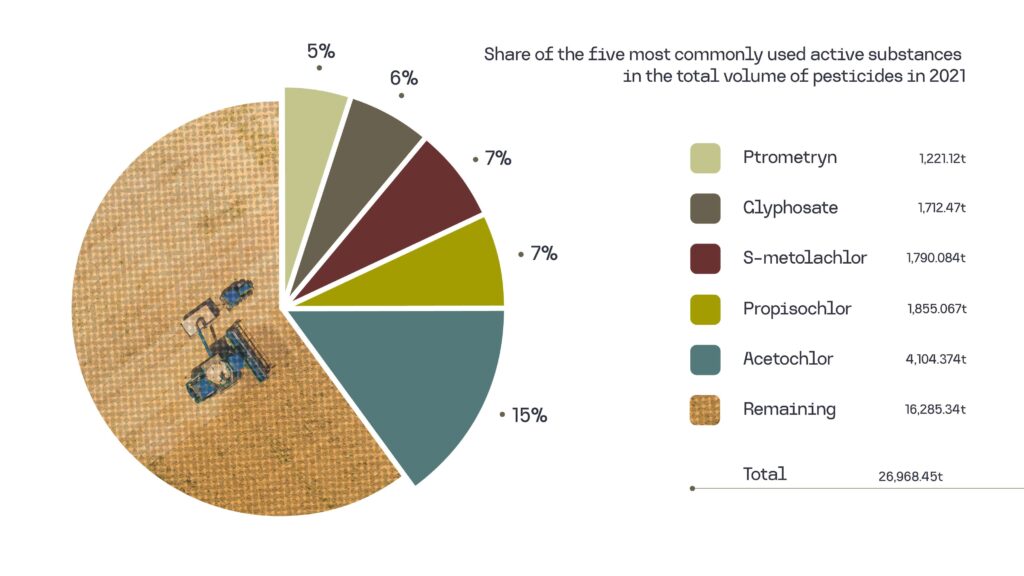

The most popular toxic agrochemicals in Ukraine are a group that could be called the ‘million-[kilogram]-pesticides’: acetochlor, propisochlor, S-metolachlor, prometryn, and glyphosate (including all its salts). From 2018 to 2024, pesticides containing these active substances were applied in quantities exceeding one million kilograms per year. The first four were recognized by the EU as too hazardous for human health and the environment and were banned, while the fifth — glyphosate — is not banned yet but is under strict control. At the same time, in Ukraine these five active substances together accounted for nearly half (47%) of all pesticides used in 2021. This group of five represents only a handful of names out of 280 active ingredients legalized in Ukraine. In total, 86 active ingredients permitted domestically are banned in the EU. Out of nearly 3,000 licensed pesticide products, these compounds are present in more than 800.

Infographic 2.

The most widespread pesticides in Ukraine are not just neatly arranged numbers in tables and charts; they are concrete risks to people. First and foremost to those who work with them in the fields, and also to the rest of the population, since agrochemicals find their way into water and food.

Acetochlor, for example, is classified by the Ukrainian Government as a Class II hazard2 According to the State Sanitary Rules and Hygienic Standards (DSP 8.8.1.2.002-98): I — extremely hazardous; II — hazardous; III — moderately hazardous; IV — slightly hazardous..

It is associated with an increased risk of cancer — particularly colorectal and lung cancer — affects fertility, and with prolonged exposure can damage internal organs.

Other commonly used herbicides — propisochlor, prometryn, and S-metolachlor — depending on their formula, are classified as Class II or III hazards. Research shows that propisochlor is especially toxic to the liver, suppresses immunity in humans and animals, and can even alter gut microflora.

In Ukraine, glyphosate is officially classified as a lower hazard Class III or IV. Even so, back in 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer at the WHO classified it as ‘probably carcinogenic to humans’.

All these substances have one thing in common: they are extremely toxic to aquatic organisms and have long-lasting effects on ecosystems.

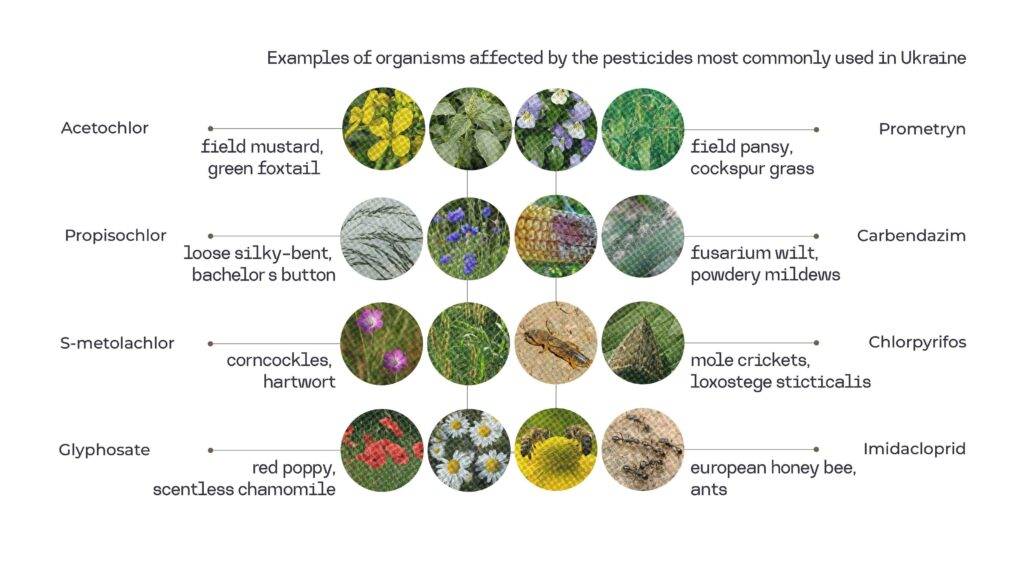

Infographic 3.

The language used by pesticide manufacturers and sellers is full of terms that create an illusion of control. One of the key concepts is the phrase target pest — the ‘pest’ at which the pesticide’s action is directed. It seems simple enough: there is a ‘target’ — a weed, beetle or rodent threatening the harvest — and there is a ‘weapon’ that promises to protect that harvest. Yet in reality, the trajectory of a pesticide’s action is rarely so linear. The active substance of pesticides can kill unintentionally — birds, pollinating insects, mammals that happened to be within reach of the chemical.

For example, the herbicide atrazine, banned in the EU since 2004, was detected by scientists in the Dnipro River along with 160 other agricultural and industrial pollutants. They noted that ‘the ecological condition of Dnipro River basin is essentially catastrophic.’ This is, unfortunately, not a solitary instance. Atrazine has the ability to accumulate in the environment; this includes entering groundwater forming other toxic compounds as it breaks down.It is often found in water bodies located far from the places where it is used. Despite being banned in the EU, atrazine continually appears in the coastal waters of its member states. Atrazine is particularly dangerous to humans since it is a probable carcinogen and can cause endocrine disruption, reduced male fertility, and cancer in workers who come into direct contact with the pesticide on farms.

However, one of the most resonant stories that completely dismantles the notion that pesticides only work where they are applied to the soil is the tragedy that occurred in the Askania-Nova Biosphere Reserve in 2021. Viktor Havrylenko, the reserve’s director, together with his colleagues, began to find hundreds of dead cranes on the reserve’s territory — hundreds of birds died, having consumed winter crops that had been treated with rodenticides in neighboring fields. Analysis showed that they had been poisoned by brodifacoum and bromadiolone — the active substances used in pesticides that are still licensed for usage against rodents in Ukraine and are classified as the lowest hazard class. At that time, more than two thousand birds and hundreds of other animals, such as hares and ruddy shelducks, died from poisoning. Havrylenko and his colleagues provided a detailed description of this situation, as well as political conflicts surrounding it, in an article. The tragedy received public attention and even led to court proceedings, and yet actual changes in pesticide regulation were insignificant — limited, for example, to a ban on using one of the pesticides, brodifacoum, within a 40-kilometer radius of Askania-Nova. As of October 2025, the companies Syngenta, Ukravit Agro, Aquarius & co., Nertus Trading House, Alpha Smart Argo, and Badvasy hold valid licenses to sell products containing brodifacoum and bromadiolone. They also continue to offer these products in their online stores.

If pesticides are used in fields, how do they end up in the environment and in the human body?

Exposure at the Workplace

Agriculture workers have the closest contact with pesticides. At first glance, statistics on occupational diseases published by the Institute of Occupational Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine appear encouraging: cases dropped sharply from 51 in 2005 to 7 in 2014. However, occupational safety experts emphasize that this is due to a reduction in state control and safety requirements at enterprises. The agricultural sector is not unique in this regard, but merely reflects what lawyer Vitalii Dudin, in the project Chronicles of Deregulation, calls the dismantling of social and labor rights in Ukraine.

The lack of state supervision means that safe conditions for working with pesticides depend entirely on the initiative of employers and employees. Of course, there are responsible agricultural producers who follow all safety regulations and care about the health of their workers. However, working with pesticides remains risky. Agricultural analyst Ihor Herasymenko provides an example: workers who were transferring glyphosate into smaller containers had to deal with toxic foam on their clothes. Another issue is outdated equipment: old spraying machines require workers to leave the cabin to adjust valves while applying pesticides in the field, thereby increasing their contact with chemicals. Personal protective equipment (PPE) reduces the risk but does not eliminate it. Even if PPE and modern machinery are available, direct contact with pesticides still poses a significant danger to workers. Moreover, when workplace safety discussions are limited to simply instructing workers, it can create the impression that safety in the workplace is the responsibility of individual workers. The issue of safety begins to appear as a choice between wearing PPE or not, rather than an assessment of whether highly hazardous substances should be used at all. Although the monthly journal Occupational Safety (in Ukrainian: “Охорона Праці”) periodically raises the issue of safety when working with agrochemicals and the responsibility of the employers, this topic is largely invisible in the Ukrainian media. Trade unions in Ukraine have made no public statements about the impact of pesticides on agricultural workers.

Pesticides in Water

One of the main ways pesticides enter the environment is through infiltration into groundwater. In Ukraine, according to the Institute of Geology, less than 25% of the population uses groundwater as a source of drinking water, however, in regions with intensive farming, groundwater is of particular importance. For example, in Kirovohrad Oblast (one of the most intensively farmed regions in Ukraine), 75% of the rural population relies on groundwater from bore-wells. The absence of centralized monitoring means that responsibility for ensuring water safety falls on the users themselves.

Wastewater from agricultural land also poses a significant threat. Despite a ban on farming on river slopes, plowing of riparian strips remains widespread. In some cases, crops are planted and sprayed with pesticides just a few meters from water bodies, causing agrochemicals to enter rivers and lakes. A report by the Ministry for Development found excessive levels of pesticides, including acetochlor, in the Vistula River basin in the Volyn and Lviv oblasts.

Pesticides in Food

Pesticides enter the human body through food. There is no systematic data on pesticide residues in food products or animal feed in Ukraine, but the scale of the problem may be indirectly assessed based on studies conducted in EU countries. According to the EU’s 2023 report, more than 40% of tested food products contained one or more pesticides. The highest residue levels were found in bell peppers, oranges, lemons, clementines, apples, pears, and strawberries, as well as in raisins, red wine, and wheat flour.

Pesticides may remain on food even after it has been processed. For example, experts at APK-Inform note that the level of chlorpyrifos in sunflower and rapeseed oils exceed the norm year after year by nearly half.

Pesticides in the Air

Agrochemicals spread through the air during aerial and ground spraying. Before the full-scale invasion, some Ukrainian agricultural enterprises sprayed fields from special aircrafts (a practice banned in the EU), often right next to residential areas (sometimes as close as 13 meters) and without regard to wind speed. This causes toxic chemicals to ‘drift’ into neighboring areas. Numerous cases confirm this, such as in Kyiv Oblast , where residents of a village reported nausea, fever, sore throat, and coughing after nearby soybean fields were sprayed with an unnamed pesticide, or cases of mass bee deaths following pesticide use on neighboring fields.

The situation is complicated by the fact that some active substances farmers sincerely consider to be safe (because the product is officially licensed) are in fact deadly for bees. For example, the neonicotinoid imidacloprid, present in 85 licensed products, kills thousands of bees every year. Even when farmers warn beekeepers in advance about spraying, the schedule can change spontaneously due to weather conditions, leaving beekeepers too little time to protect their hives and save the bees.

Accidents and Emergencies

Accidents during the transportation of pesticides are another source of chemical contamination in the environment. For example, in 2019, an accident in Vinnytsia Oblast caused a spillage of a ton of insecticide containing chlorpyrifos and cypermethrin into the Ros River. However, pesticide-related incidents are not limited to the places where they are used. China, the world leader in pesticide production, regularly appears in the news because of its large-scale accidents. For example, the disaster at the Tianjiayi Chemical plant resulted in 78 deaths and more than 600 injuries.

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the risk of pesticides entering the environment has increased significantly, as Russia purposely targets agricultural enterprises, including warehouses with agrochemicals. According to Ekodozor, as of August 2025, open sources reported 3,799 accidents as a result of Russian attacks on 1,960 facilities, 472 of which were in the chemical, agricultural and food industries. In other words, when Russia strikes agricultural facilities, it destroys not only fields, crops, or grain storage facilities but also pesticide warehouses, effectively turning agrochemicals on Ukrainian territory into a kind of chemical weapon. One example of such damage is the destruction of Kakhovka dam by the Russian army. As geographer Ihor Kotovsky notes, as a result of the disaster, DDT , an extremely toxic pesticide (and the main protagonist of the book Silent Spring mentioned at the beginning of this article), could have entered the groundwater, the Dnipro-Bug estuary, and the Black Sea. Why a significant amount of this chemical, which has been banned in Ukraine since 1997, remained in the Kherson Oblast is a matter for another discussion.

Which crops require the most intensive use of pesticides?

More than two-thirds of all pesticides used in Ukraine are herbicides. Their chemical formula is designed to target ‘weeds’ — the quotation marks here are intentional. The Law of Ukraine ‘On Plant Protection’ defines a weed as any vegetation that is undesirable from an agricultural point of view. It is a plant that grows in ‘farmland, crop fields, and plantations of cultivated plants, that competes with them for light, water, and nutrients, and also contributes to the spread of pests and diseases.’ It is no surprise that in a country where agriculture accounts for one of the largest shares of GDP, the plant protection law does not protect all plants equally. From a legal standpoint, agricultural crops are far more protected than, say, steppe vegetation. In fact, ‘plant protection products’ is the official synonym for pesticides. But this protection has a downside: it comes at a high price for many other living beings, including humans.

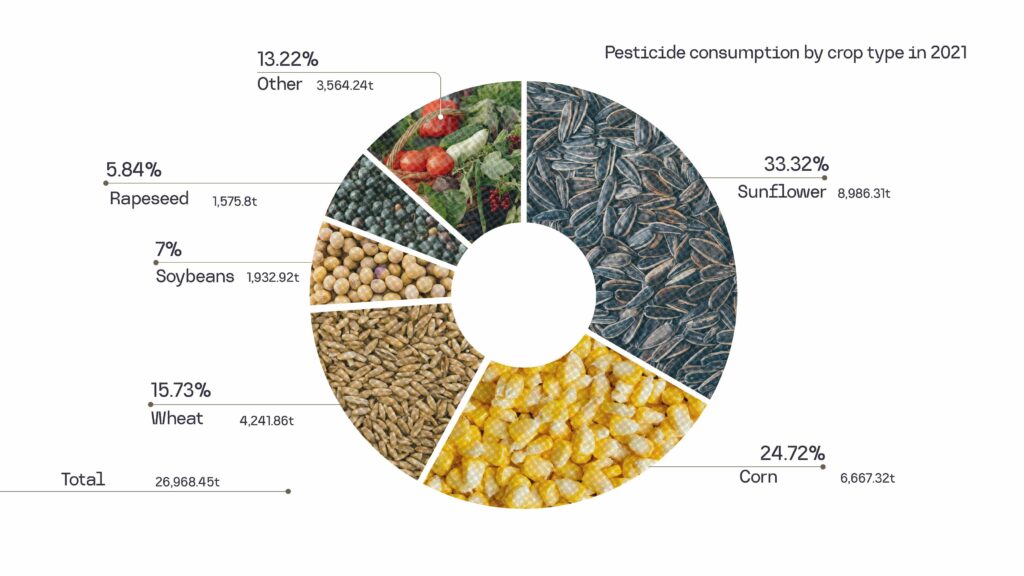

In Ukraine, the main ‘consumers’ of pesticides are producers of export-oriented crops. In 2021, the cultivation of five crops — sunflower, corn, wheat, soybeans and rapeseed — accounted for 87% of all pesticides used in the country. By contrast, all other crops combined, mostly vegetables and fruits intended for the domestic market, required only 13% of the pesticides (see Infographic 4).

Infographic 4.

In news coverage about Ukraine, both in domestic and international media, the dominant image is that of the ‘breadbasket of Europe’, and sometimes even of the world. An article by the European Commission, for example, describes disruptions to Ukrainian agricultural exports as a threat to global food security, while the popular science outlet Wired goes so far as to claim that the war in Ukraine risks causing worldwide famine. These statements are partially true: Ukrainian grain has indeed been and remains important for many countries in Africa and the Middle East. Ukrainian wheat, in particular, accounted for 80% of Lebanon’s grain imports. This ‘poor countries’ framing appeals to emotions: if the war continues, the narrative asserts, people will starve. However, this is not the full picture, as it obscures other markets that are decisive for Ukrainian farmers’ choice of crops.

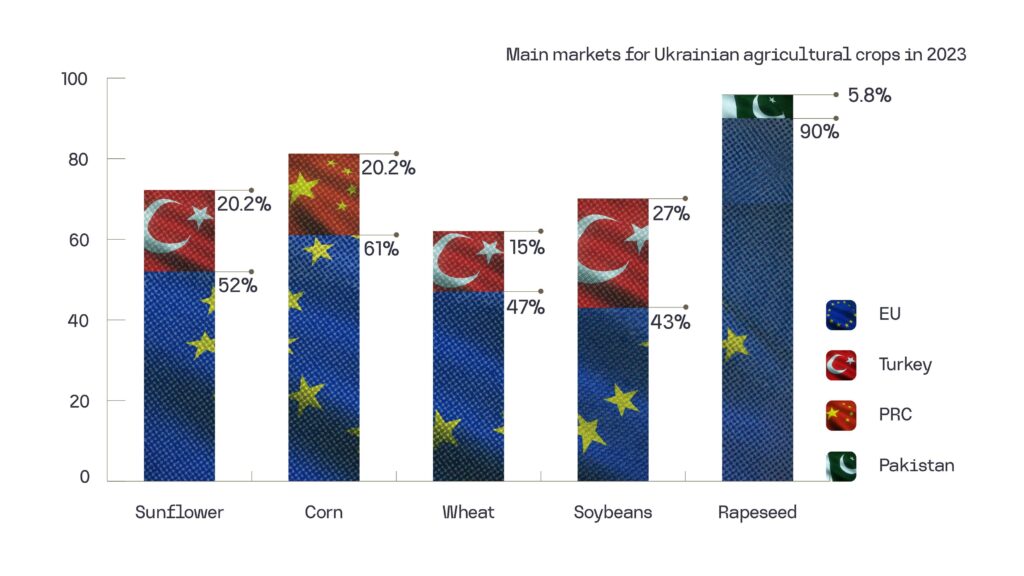

Looking at trade data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity, one can see that, in fact, most exports went not to countries in Africa or the Middle East, but to the European Union. In 2023, 43% of the total wheat harvest, 61% of corn, and nearly 90% of rapeseed were exported to the EU (see Infographic 5).

Infographic 5.

Another aspect to consider when discussing pesticides is the sheer scale of agricultural production. Ukraine is among the countries with the highest proportion of arable land in the world; arable land accounts for 57% of the country’s territory3 Data as of 2022, excluding temporarily occupied territories.

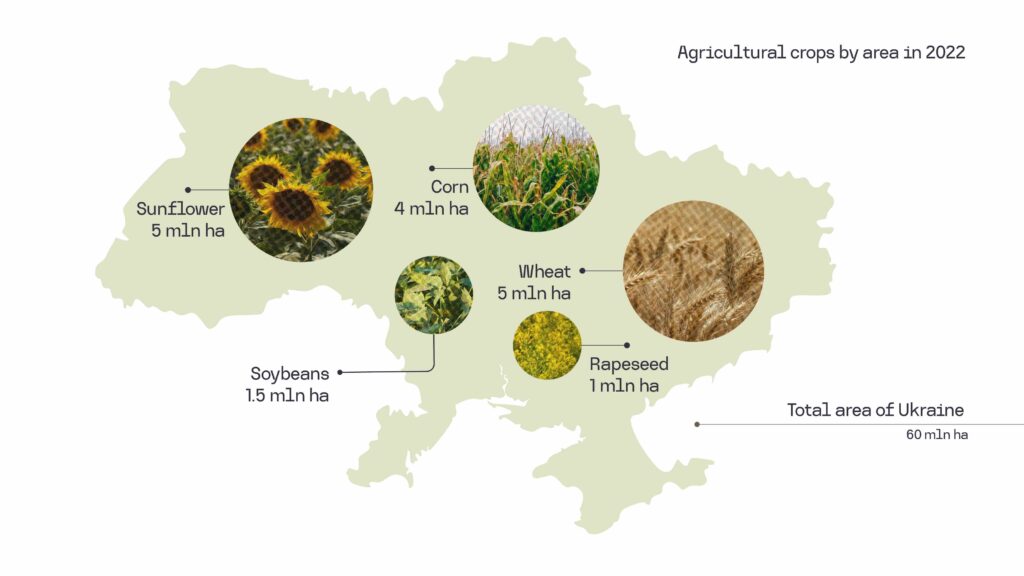

. For comparison: in Germany it accounts for 33%, in Poland 37%, and in France 34%. In Ukraine, it is about 33 million hectares, and this estimate does not include the illegal ploughing of slopes or protected areas. Five export-oriented crops — sunflower, corn, wheat, soybeans, and rapeseed — occupy two thirds of all arable land, which is about 40% of Ukraine’s territory (see Infographic 6). This is more than the agricultural land area of Germany and Poland combined. Since pesticides are used on nearly all of these fields, approximately 40% of Ukraine’s territory is covered with toxic pesticides every year.

Infographic 6.

The way these crops’ production is structured is also telling. According to the data from the State Statistics Service, the main producers of sunflower and corn are major agricultural holdings, such as Kernel, ViOil, Allseeds, MHP Agroton, and Ukrprominvest-Agro. Each of them controls more than 3,000 hectares of land. In 2022, these companies collectively harvested 27% of the total corn crop, although they account for only 1.2% of the total number of agricultural enterprises. Sociologist Nataliia Mamonova calls this situation a ‘bimodal structure of agricultural production’: large companies focus primarily on exports, while the domestic market is supplied by small and medium-sized farmers who grow mainly vegetables and fruit.

What about the state: where can official information be found and who shapes agrochemical policy in Ukraine?

At the legislative level, the main document in this area is the Law of Ukraine ‘On Pesticides and Agrochemicals’ from 1995. This area is also regulated by the laws ‘On the Public Health System,’ ‘On Plant Protection,’ and the State Sanitary Rules ‘Transportation, Storage, and Use of Pesticides in the National Economy.’

The main source of information about pesticides currently licensed in Ukraine is the State Register of Pesticides and Agrochemicals Authorized for Use in Ukraine (hereinafter — the State Register). While the register is not as user-friendly as its European counterpart — the EU Pesticides Database — it contains a great deal of valuable information for anyone who seeks to understand which products are permitted in Ukraine. As of 2025, nearly three thousand products are licensed in Ukraine, of which approximately one third belong to the most hazardous Classes I and II.

The State Register is undoubtedly a useful tool, but it does not resolve the problem of the non-transparent process of obtaining licenses itself. The registration and renewal of pesticide licenses takes place as a closed-door process between the applicant company and the state: the public has no means of influence. In theory, the state can refuse to extend a license for a product if it has evidence of its harmfulness. However, there is no defined procedure for how the public or scientists could provide such data to state institutions specifically at the license review stage. In addition, the documentation on the product, which serves as the basis for issuing a license, is protected as a trade secret. Even if this documentation can be obtained, it is prohibited to use this data without the permission of the licence-owner.

The State Register is not the only document regulating permitted pesticides. In addition there is a list approved by the Ministry of Health — the list of the State Chemical Commission of Ukraine — which identifies 87 pesticides prohibited for use or registration. It bans the use of hazardous agrochemicals such as DDT, aphos, 2.4,5-T and others. However, this list was approved back in 1997 and no updates have been made since. Occasionally, pesticides that are not included in either the State Register or the list of prohibited substances show up elsewhere. One example is dichlorvos – a chemical not included in either of the two lists – was found to exceed the norm in the Ministry of Development study of river pollution.

The association agreement with the EU is pushing the Ukrainian government to make changes in order to bring its pesticide regulations into line with European standards. In September 2025, Ukraine completed a negotiations stage with the EU on agricultural policy. Although the details of the negotiations have not yet been disclosed publicly, some changes have already been observed — for example, Ukraine’s adoption of the REACH and CLP regulations, which aim to improve access to information regarding the hazards of pesticides. Nevertheless, these initiatives predominantly affect labelling regulations rather than the level of public or worker awareness of the risks.

The process of aligning Ukrainian and EU legislation will also involve a review of the pesticide registration procedure. At present, the EU registers both the main active substance of a pesticide and the formula of the product itself (which may contain a small percentage of other substances). The status of any active substance can be checked in the EU Pesticides Database. Meanwhile, Ukraine does not yet have a separate list of active substances, and the State Register of Pesticides keeps records based on product formulas. This means that there are dozens of products with identical formulas from different companies on the Ukrainian market, and if one of them does not have its license renewed (due to, say, new information about environmental harm), the others remain on the market.

The influence of the European Union’s regulatory demands exists alongside the influence of agricultural businesses on agricultural legislation. In 2019, for example, the Parliament considered draft law No.2289 on amendments to Article 4 of the Law of Ukraine ‘On Pesticides and Agrochemicals’ regarding the import of pesticides into the customs territory of Ukraine. The authors of the draft were six members of parliament, among them Oleh Tarasov — a businessman and son of Serhii Tarasov, an agro-oligarch wanted by the Security Service of Ukraine and owner of the I&U; Ivan Chaikivskii, an agricultural businessman; Mykola Kucher, former director of Zernoprodukt MKP CJSC, and his daughter Larysa Bilozir. In the explanatory note, the MPs promised that the changes they proposed would reduce the pressure of agricultural production on the environment, lower costs for farmers, and decrease the final price for consumers. However, the key proposal of the draft law was to abolish the requirement for official registration of imported pesticides in the country of production, meaning that if the chemical is imported from China to Ukraine, it doesn’t need to be officially registered in China.

The Parliament’s expert-scientific committee concluded that such a change could lead to uncontrolled testing of chemicals that are not registered in other countries, and potentially result in harmful consequences. It was also noted that the proposition contradicts Articles 16 and 50 of the Constitution of Ukraine, which guarantee ‘the ecological safety of Ukraine […] and the right of the people to an environment that is safe for life and health.’ Some MP’s, including Olha Vasylevska-Smahliuk, expressed concern in the media about the unrestricted import of suspicious chemicals into the country.

Despite these concerns, the Parliament voted in favor (224 votes, almost unanimously by the Servant of the People party), thereby fulfilling the interests of the agricultural industry. As of 2025, little is known about the consequences of implementing this law, since the government has not published any monitoring data.

In July 2025, the Ministry of Agrarian Policy announced the development of a National Action Plan aimed at reducing the negative effects of plant protection products. The Ministry stated that the plan is being prepared in cooperation with representatives of the French Embassy, the French state agency Expertise France Group AFD, and other representatives of the state, academia, and business. So far, no details of the plan have been disclosed, nor has there been any mention of the involvement of civil society organizations.

In the same month, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine issued Resolution No. 903, which merged three ministries — the Ministry of Economy, the Ministry of Ecology and the Ministry of Agrarian Policy— into the Ministry of Economy, Environment and Agriculture of Ukraine, informally known as ‘Ministry of Resources’ and officially abbreviated as ‘Ministry of Economy.’ Over the past five years, there have been several attempts to form such a ‘mega-ministry.’ This time, the merger is being positioned as an effort to create a single point of contact within the Ukraine Facility instrument. The obvious conflict between the current function of the Ministry of Environment in issuing licenses for agrochemicals and the Ministry of Agrarian Policy remains without official comments or explanations.

Agrochemical Production and Supply Chains

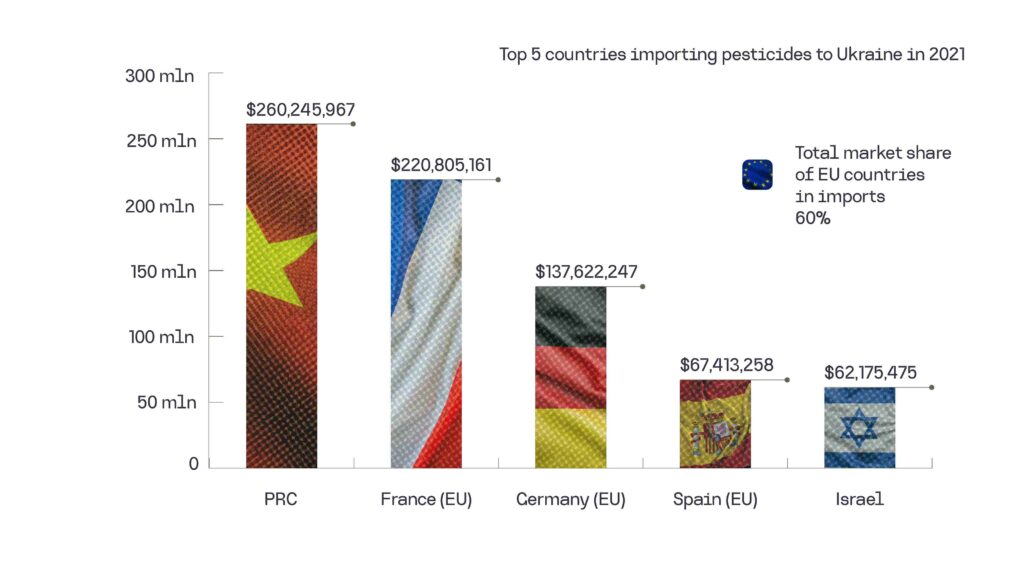

Ukraine primarily imports pesticides. The main supplier for many years has been the European Union, especially France and Germany. In 2021, the EU accounted for 60% ($1.02 billion) of all pesticide imports to Ukraine. Another important supplier is China.

Infographic 7.

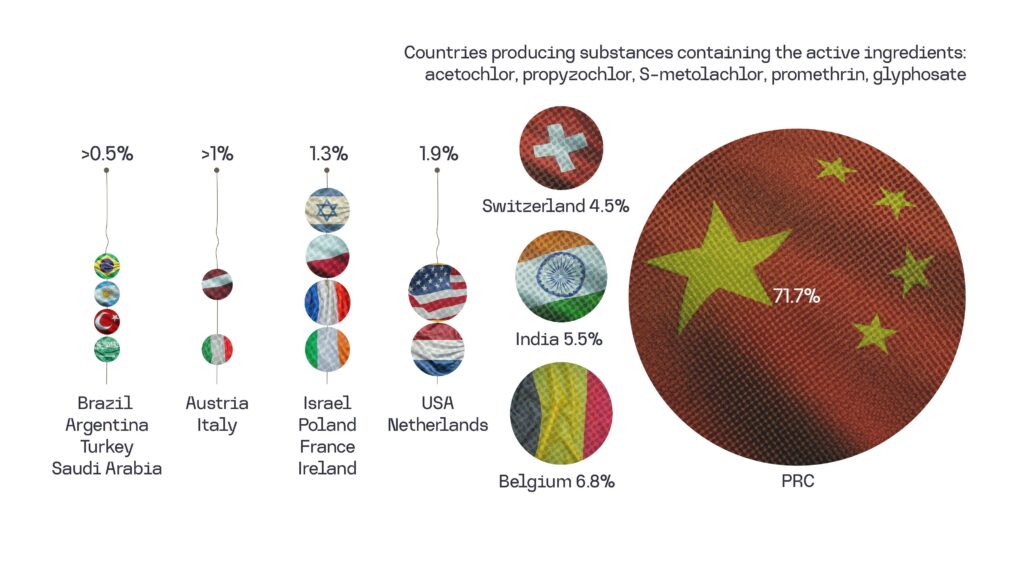

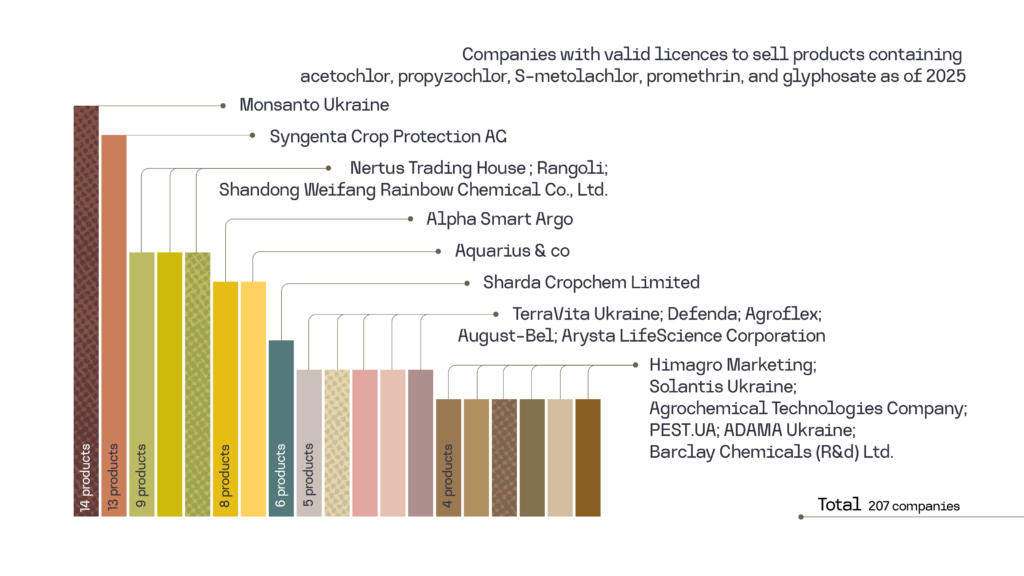

However, it is more worthwhile to examine the origins of the five most toxic and, at the same time, most widely used pesticides — acetochlor, propisochlor, S-metolachlor, prometryn, and glyphosate. Some of these compounds, which are banned in the EU, are produced by European companies. The EU ban applies to their use within EU member states, but not to their production, and so the pesticides are exported to third countries, including Ukraine. At the same time, most highly toxic substances are imported from China. Almost all active substances on the Ukrainian market come from Chinese factories (see Infographic 8). As of September 2025, more than 200 products containing these five key active ingredients are registered in Ukraine.

Infographic 8.

Only a few companies control the entire chain from producing the active ingredient to selling the final product and to its registration in Ukraine. For example, the Israeli company Adama Agan manufactures and supplies acetochlor-based products to Ukraine using its own production facilities.

A more common model works differently: a Ukrainian license-holding company purchases the product from a foreign manufacturer, who in turn buys the active ingredient from yet another company. This is the case with one of the largest players on the market, Nertus Trading House. It collaborates with the Hungarian company Peters & Burg Ltd and actively sells products containing propisochlor. The companies that sell the five most widely used pesticides are listed in Infographic 9. However, the ultimate point of origin almost always is a Chinese industrial facility.

Infographic 9.

Illegal Market

What is not included in the official statistics is the clandestine circulation of pesticides: banned, counterfeit, smuggled, and other products of dubious origin. Investigations by the National Police, the State Customs Service, the Prosecutor General’s Office, and the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) have uncovered a large-scale illegal scheme for the production and sale of pesticides, operating not only in Ukraine but also in several EU countries, involving hundreds of tonnes of illegal products worth over $2.3 million. In 2018, UNEP estimated that illegal pesticides accounted for 25% of the total market in Ukraine. New cases, including those uncovered by the Economic Security Bureau in 2025, confirm that the problem remains systemic and the war has only worsened the situation.

Resistance to Toxicity: Beekeepers, Legal Activists, and the Role of the Media

Ukrainian beekeepers are among the most active opponents of pesticides. United in the movement ‘Ukraine Against Pesticides’, they raise the alarm, reporting the death of thousands of bee colonies after fields have been sprayed with pesticides. In July 2025, the news outlet South Today reported the death of millions of bees, as well as the entire population of wild pollinators and insects within a 20 km radius of the site where pesticides were used in the Odesa Oblast.

It is among beekeepers in Ukraine that one can find examples of the systematic use of existing legislative instruments to pressure the government to reduce pesticide use. For example, in April 2019, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine registered a draft resolution ‘On the prohibition of the import into the customs territory of Ukraine and the use in Ukraine of certain hazardous pesticides.’ The Ukrainian Beekeepers’ Union proposed banning the import and use of all agrochemicals containing atrazine, acetochlor, glyphosate, imidacloprid, clothianidin and thiamethoxam. If the ban had been implemented, it would have affected more than 300 products sold in Ukraine by Bayer, BASF, Syngenta, Badvasy, Aquarius & co, Nertus, Monsanto, Rangoli and others. The head of the Ukrainian Agri Council immediately opposed the ban, claiming that it would lead to a decrease in harvests and a significant increase in water consumption. The Cabinet of Ministers did not consider the draft resolution, and a public petition in support of the ban did not gather enough signatures.

A similar scenario unfolded with the beekeepers’ demands to create a public registry of all cases of bee poisoning incidents in Ukraine, with access to the status of investigations, as well as with a draft law on beekeeping protection that would have introduced heavy fines and criminal liability for the poisoning of insects.

However, it is not only beekeepers who are calling for stricter regulation of pesticides in Ukraine. The environmental NGO Ecology, Law, Human (in Ukrainian: «Екологія, Право, Людина» (ЕПЛ) has been emphasizing for decades that the government fails to control pesticide use. Activists have repeatedly appealed to lawmakers to ban all pesticides not approved in the EU, or at least to ban atrazine, glyphosate and acetochlor. Their demands remain unsatisfied.

Local authorities sometimes issue statements about the dangers of pesticides, and yet there is no regular monitoring or public reporting regarding their impact on health and environment. Meanwhile, this topic is often covered by the media: UP (Ukrainska Pravda) journalists write about the harm of pesticides to pregnant people, especially in rural areas, NV (The New Voice of Ukraine) reports on how chlorpyrifos leads to brain development delays, and Med Oboz talks about cancer cases caused by pesticides. In the absence of official statistics, national and regional media play a key role in covering cases of human poisoning, bee deaths, and other incidents related to pesticides in Ukraine.

The struggle for a safer environment is complicated by the fact that the organising logicsof agriculture, ecology, economics, and health care often do not align or are in direct conflict with each other. And yet, even under such conditions, experts in the field of the environment, occupational safety, and even some representatives of agricultural production who have refused to use synthetic pesticides are trying to change the situation.

Overcoming the toxic legacy: how to reimagine agricultural production?

In Ukraine, as in other countries, farmers are becoming increasingly aware of the scale of the pesticide problem and are looking for alternative ways to grow food. The international organization La Via Campesina, for example, has long supported such changes, advocating what it calls ‘agro-ecological farming’ — a practice and philosophy of agriculture guided by a seemingly simple, yet fundamental question: how to grow food in a way that is both environmentally responsible and socially just? Although there is no representative office of this organization in Ukraine yet, there are dozens of farms that, when cultivating their products, work with the entire ecosystem in mind: with the soil and its inhabitants, insects, birds, and others. Among them are biodynamic, organic, and even conventional farmers who have deliberately chosen to grow a more diverse range of crops.

However, it would be misleading to reduce pesticides use to a matter of purely individual choice by a farmer or enterprise. Ukraine’s agriculture is largely shaped by the demand of foreign export markets. Here, it is important to understand the historical continuity of this hierarchy. It is often argued that Ukraine has always been an agrarian country, which supposedly justifies its role as a supplier of agricultural raw materials. But historians such as Volodymyr Kulikov remind us that this continuity did not emerge on its own due to natural factors. Instead, it is the product of a specific form of economic relations. From the end of the 19th century until the collapse of the Russian Empire, Ukrainian grain accounted for a significant part of the Empire’s exports. Under Soviet rule, the exploitation of Ukrainian lands for all-Union needs only reinforced the export orientation of the Ukrainian economy. After gaining independence, Ukraine continued its focus on agriculture exports and, despite the war, remains one of the world’s largest exporters of industrial crops. This continuity of export dependence determines not only the structure of the Ukrainian economy but also what is grown in Ukrainian fields, the scale of pesticide use and, ultimately, the level of toxicity.

There can be no illusion about simple solutions, as an immediate ban on highly toxic pesticides is neither politically feasible nor a realistic scenario. The knot of pesticide use is not easy to untangle: tug sunflowers on one end, and the EU market, a factory in China, data sets, and lawmakers’ offices show up on the other. Even if the EU stops supplying Ukraine with pesticides that are banned within its own borders, we will still be dealing with China, where most of the most toxic chemicals come from. Even if farmers switch to less toxic products, they continue to work in a globalized capitalist agricultural industry that demands more, faster, cheaper. Currently, the use of pesticides is a key component of the production process for farmers who sell their crops on international markets. Today it may be difficult to imagine a complete abandonment of hazardous pesticides, and yet such a possibility must exist at least on the horizon of political imagination. After all, this issue is not only about revising our own past and overcoming historical dependence, but also about whose interests determine the acceptable level of damage from agrochemicals and, ultimately, it is a question of democratizing the mechanisms for controlling hazardous chemicals.

The dark side of agrarian optimism does not disappear simply by pretending it is not there. Ukrainian fields are not only an endless yellow horizon of wheat or sunflower, but also a battleground over which plants and which organisms we truly choose to protect. Sure we can be proud of Ukrainian grain on the global market, yet we should not close our eyes to the dark side of this export — poisonous, barely visible, and persistent, settling in the soil, water, air, and our bodies.