Odesa has long had a reputation as a city of drifters and seekers. Its mild southern climate and historic status as a “free port” made it a magnet for refugees of various nationalities, the destitute, those in search of shelter or work—and for many, a place where spending the night outdoors felt less brutal. Since the beginning of russia’s full-scale invasion, the city has become a refuge for people whose homes have been destroyed, whose towns are under occupation, and those who came looking for decent jobs only to fall into cruel cycles of exploitation. Behind the façade of Ukraine’s most popular unoccupied resort—where hookah smoke curls above seafront cafés and sycamores cast shadows along wide alleys—live the city’s homeless and impoverished.

They may go unnoticed, but they are everywhere: in parks, squares, the catacombs near the sea, on pieces of cardboard outside the Opera House, in abandoned offices near the Pryvoz market, in manholes, squats, shelters, even under the mayor’s office. You’ll find them reaching out a hand for help on newly renamed central streets or hauling bags of scrap metal to recycling points.

The exact number of homeless people in Ukraine—or even in Odesa—is impossible to determine. According to the Ministry of Social Policy, around 33,000 individuals sought official assistance in 2019, but these figures reflect only those who asked for help. The actual number could be many times higher.

Comprehensive research on homelessness in Ukraine is scarce, and the issue remains largely ignored by the state—despite massive internal displacement, the heightened vulnerability of internally displaced persons (IDPs), and rising poverty levels. Part of the problem is methodological: homelessness is often hidden, with individuals too stigmatized or fearful to seek assistance, and many migrate frequently between cities. But the core issue lies in a lack of political will to study the problem in the first place. Tellingly, one of the few notable surveys in recent years wasn’t conducted by the government, but by the religious charity Depaul Ukraine. In 2024, it found that 22% of people currently sleeping on the street or in shelters are internally displaced persons.

The absence of reliable data does not erase the reality of the crisis. Behind the dry numbers—or their absence—stand living people who face daily, concrete threats: hunger, cold, illness, addiction, violence, constant fear for their lives, social stigma, and crushing loneliness.

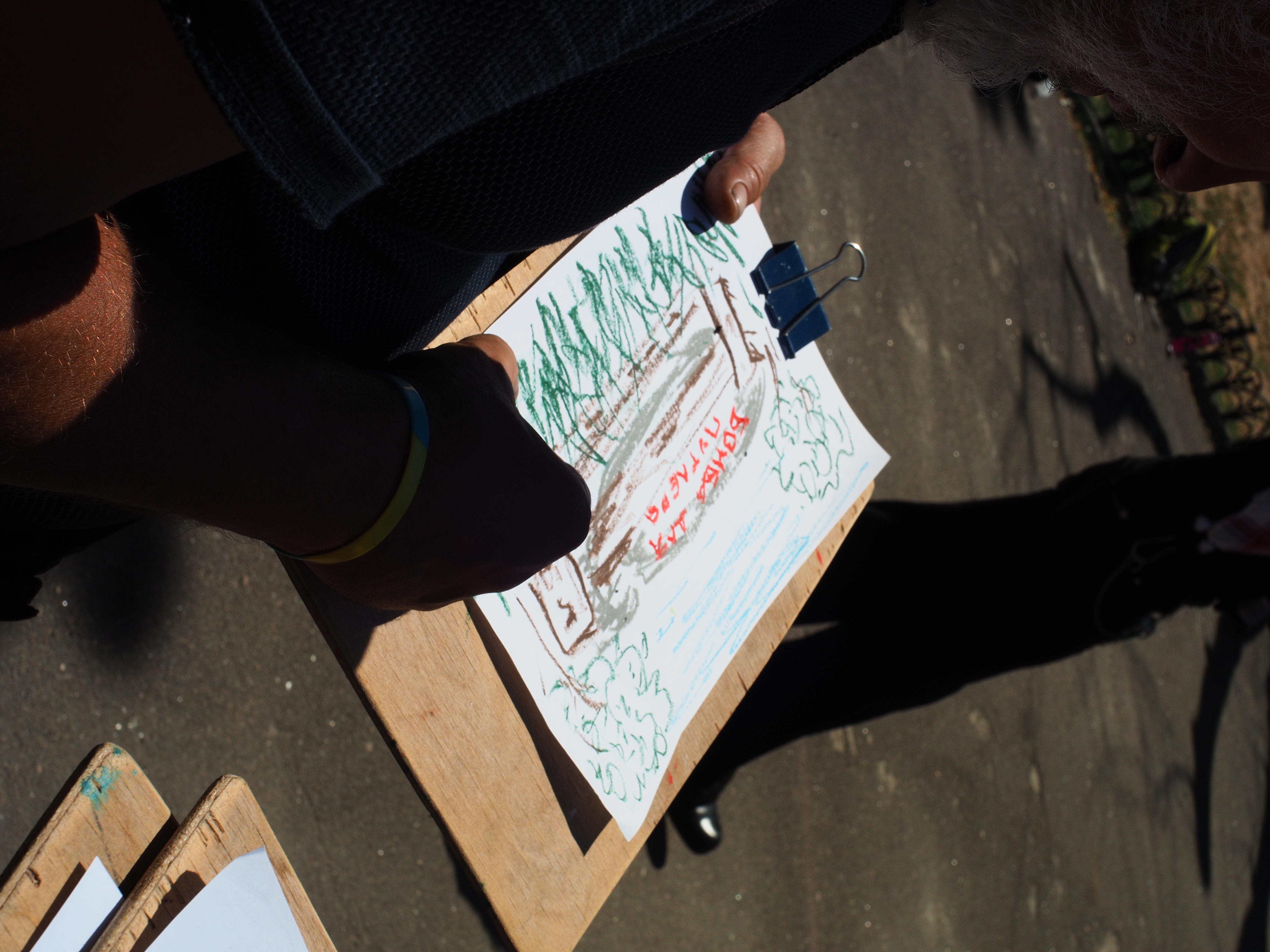

Through the work of the local initiative Street.Aid.Daily, which provides weekly aid to Odesa’s homeless population, I had the chance to speak with several individuals—some of them have been living on the streets of Odesa longer, while others for a shorter time. We talked about visible and invisible work, temporary shelters, solidarity, war, a sense of safety, shame, and the awareness of being homeless.

Photo: Borys Ukrainskyi

Life in the Open

We see Ruslan (name changed) at almost every aid distribution. If he’s not there, he’s probably working—hauling scrap metal, mixing cement on a construction site, or resting after a heavy night of drinking following a hard day’s work the day before. He’s around forty years old, short in stature and dark-skinned, with a distinctive personal style—something about him reminds you Tyler Durden from Fight Club. Despite living rough and doing gruelling physical work, his white sneakers and fingernails are always clean.

Originally from the Dnipropetrovsk region, Ruslan came to Odesa in the summer of 2021 with a clear plan: earn 60,000 UAH doing odd jobs and return home with the money. He worked six days a week, had only one day off, and tried to save every penny. But over time, the work dried up, and most of his earnings went toward hostel fees.

After the full-scale invasion began, things worsened. Construction sites in the city nearly came to a halt. Where fifteen workers were once hired, now maybe two or three are taken on. These days, Ruslan works two or three times a week—when he’s lucky. On other days, he collects scrap metal or “dives” into dumpsters, searching for anything he might resell.

Unable to afford housing, Ruslan initially lived rough and spent nights sleeping in parks. Later, he met another homeless man who showed him how to set up a shelter in a manhole near a heating pipe.

“I still live in that manhole. Yes, it gets a bit chilly in winter and stuffy in summer, but if I crawl in at night, it’s livable. Right now, I’m doing okay down there—I don’t really complain much. The only problem is when it rains; I get soaked. I lay down a plastic sheet, lie on it, then cover myself with another sheet. Of course, I have a blanket on top. My manhole isn’t very deep. When I breathe inside, if it’s -10°C outside in winter, it’s about +3°C for me inside. I think that’s enough. I take off my pants, jacket, and one sweater—and that’s how I sleep.”

For Ruslan, the manhole is more than just shelter from the elements. Unlike the streets or temporary shelters, it feels like his own home—a personal space he can rely on and take responsibility for. It’s a place where he can find privacy—a privilege many of his homeless acquaintances lack. According to Ruslan, he feels safe there and even receives support from his “neighbors”—the people living above ground.

“By now, pretty much everyone knows me: the drivers, the soldiers. Sometimes I just lie there, reading a book, when someone calls out, ‘Hey, are you alive? Come on, poke your head out!’ I look up, and there’s a bag of food and a pack of cigarettes waiting for me. I never ask for anything. Some people just say, ‘Here, take it.’ There are two women who walk their dogs nearby—they know I live in that manhole. One of them taps on the lid with her foot. I lift it up, and she says, ‘Here you go,’ handing me something. That’s it.”

Many people experiencing homelessness avoid official shelters, driven by mistrust, stories of harsh conditions, loss of personal freedom, excessive oversight, or even exploitation. Still, during the cold season, many turn to night shelters when staying outside becomes too dangerous.

Public spaces in cities often attract homeless people because they are open and don’t require negotiating or defending a spot by force. Adapting to the season, their health, the level of danger, and the resources they have, people find temporary shelter in parks, stairwells, trains, courtyards, beaches, basements, cemetery vaults, near heating pipes, or in abandoned buildings. To survive, they rely on creativity in finding a place to sleep.

Photo: Borys Ukrainskyi

At the same time, staying in such places comes with serious risks—attacks, police raids, and the constant threat of losing personal belongings. Many are forced to sleep on hard benches, cold pavement, or even while sitting upright, just to avoid falling into a deep sleep and becoming easy targets for violence.

One person we’ve come to know well is Tamara (name changed), a Romani woman who ended up on the street after years of domestic abuse. Her husband beat her regularly and eventually took her children away. But, as Tamara tells it, she feels even more anger toward her mother—who forced her into marriage with an abuser and never gave her a chance at education. Now in her fifties, Tamara still cannot read or write.

Today she stays at a municipal women’s shelter. But just a few years ago, she was living in the open—on a bench in one of Odesa’s public squares. Over time, she gathered a number of personal items, which she kept on or near the bench. But she often had to fend off municipal workers who, under orders to “keep the park clean,” would throw everything away. In this context, “cleanliness” often means erasing the traces of people society prefers not to see.

“The street sweepers, the men—they clean everything up. And what can I say? Everything I had was in that coat. I’d left some money in the pocket, even an old tablet I used to watch movies on—it was all taken. They grabbed it right out of my hands. I swear to you, everything—just gone. One time, the woman in charge was reasonable—she came and warned me first. But this time, it was like someone sent her specifically after me. They all sat there laughing as she took my things.”

In winter, Tamara would go down into underpasses, stay at the train station, or—if she was kicked out—ride commuter trains between nearby towns just to keep warm. She says the hardest part was making it through the night: when your body is exhausted but the cold and the danger make it nearly impossible to fall asleep.

“If I had nowhere to sleep, and the station staff were being nasty, I’d take a train to Kotovsk [now Podilsk in the Odesa region]. I’d get some sleep on the train—it was warm. Not long ago, I even travelled all the way to Vapniarka [a town in Vinnytsia region, 400 km from Odesa]. Just back and forth on those trains in winter, for two or three days at a time. What else could we do?”

Some people choose to sleep in abandoned buildings. These offer at least a minimal sense of privacy and temporary shelter. But they offer no real safety—there’s the risk of collapsing roofs, fires, and conflict with others inside, some of whom may act violently.

Photo: Borys Ukrainskyi

Homeless women are particularly vulnerable to violence. Life on the streets brings a constant risk of assault, sexual harassment, and other threats. Our acquaintance Olya (name changed), who has been living rough for nearly twenty years, told us that while she often slept in abandoned buildings, she never did so alone. She always tried to stay with someone—friends or people she knew and trusted.

“It could be terrifying, especially after dark—you never know who might come out of nowhere or what they might do to you when you’re alone. That’s why I always tried to have someone with me. It felt a bit safer… The people around can be dangerous. You never know who you’ll run into… I only stayed there [in the abandoned places] when I was with someone I trusted. That’s really important for a woman living on the street.”

Olya shared accounts of the violence she had experienced over the years: attempted rape, robbery, and brutal beatings. In one case, she was attacked so viciously she lost consciousness. Her attackers, thinking she was dead, left her to die. But somehow, she managed to get to a hospital and receive help. Olya added that if she had been able to see her wounds, she would have stitched them herself—she’d done it before, using whatever she could find.

She didn’t go to the police. Her attackers had disappeared, there was little chance of proving anything, and she had no trust in law enforcement. According to Olya, the people who attacked her weren’t other homeless individuals, but rather “rich boys” who knew they’d face no consequences. Even among the people she shared the streets with, Olya kept her guard up. Trust, in such an environment, could quickly become a deadly risk.

“As soon as I sensed danger, I walked away. Because I knew that if someone gave me free booze, I’d have to pay for it later—and I won’t say how, you can guess. These so-called gifts always come with a price.”

The Invisible Economy of the Street

Olya was just a teenager when she found herself living on the streets. At 14, her mother—a devoutly religious woman—threw her out of the house, unable to accept her daughter’s way of thinking or her new social circle. Nearly two decades have passed since then, most of them without stable housing. To survive, Olya took on whatever work she could find: washing dishes, cleaning apartments, caring for animals, hauling construction debris, doing basic renovation work. When she couldn’t find any odd jobs, she searched through dumpsters for scrap metal or anything of value. At times, she asked strangers for money on the street.

For people without stable housing or access to formal employment, this kind of informal economy is often their only means of survival. It consists of occasional and short-term work: one-off jobs, collecting recyclables, searching for and selling found items. There are no labour contracts, no taxes, and no social protections. Whatever they manage to earn is usually spent immediately—mostly on food, shelter, and medicine, and sometimes on alcohol, cigarettes, or drugs.

Among those living rough and trying to earn money, there are typically three main income strategies. The first is short-term, informal labour. The second involves collecting recyclables—metal, cardboard, bottles—or searching through dumpsters for items that can be sold or traded. The third is direct solicitation: asking passersby for help. These strategies often overlap and shift depending on the season, the availability of informal work, and a person’s physical and emotional capacity.

Photo: Borys Ukrainskyi

Odd Jobs

Homeless people often pick up odd jobs on construction sites, working as assistants or general labourers. According to Ruslan, unofficial middlemen from construction sites—known as “runners” among the homeless—often visit places where unhoused people gather, offering them day jobs. The jobs are hard and poorly paid: Ruslan earned about 500 UAH a day. Another acquaintance, Svitlana, said she made 380 UAH for a 12-hour shift at a bread factory.

“Twelve hours on your feet, 380 hryvnias. Hot loaves come flying off the belt, even gloves don’t help, and you have to place them neatly on the shelves… The turnover is constant—people last a day or two at most.”

Such work is especially difficult for people with disabilities or elderly people, who often accept exhausting jobs out of desperation. Sasha, a young man from the Sumy region and a refugee, had sought help several times at aid distributions organised by activists. He said he has a disability and can barely walk. He tried to find occasional work, but the physical demands were too much—he was forced to give up.

“I can’t lift anything heavier than twenty kilos. But now every job for labourers—concrete, gas blocks, bricks—it’s all heavy lifting. Basically, there’s no way I can do that with my health.”

Many homeless people are recruited for seasonal work in the fields of Odesa and neighbouring regions. Several people we spoke to described extremely harsh working conditions—long hours from early morning until night, often under the scorching sun, with little rest and no protection from the weather. Beyond physical exhaustion, such odd jobs sometimes verge on exploitation, and in certain cases resemble modern slavery. People can become dependent on employers, with no way to leave freely. Often they are offered food and shelter in exchange for labour, while the promised wages might not be paid.

Homeless individuals may also work for the city—most often as street sweepers or cleaners in municipal parks, green areas, and other public spaces. This kind of work may provide access to storage rooms or temporary shelters managed by municipal services. However, as Olya explained, it is still physically draining.

“In autumn and winter, I know I’ll have to work—those are the hardest times for me. That’s when I’ll take whatever job I can get. But not as a street sweeper—I can’t handle that. It’s just too hard. Clearing snow takes strength—you have to break ice, dig with a shovel. And you can’t even burn the leaves you collect—you get fined for that. No, I couldn’t manage that. Any other job—cleaning shops, washing windows, hauling construction waste—I can do. If I know how to do it, I’ll manage. But working outside like that—that’s the one job I can’t take.”

Scavenging

Many homeless people collect waste paper, scrap metal, bottles, and other materials for recycling. This work is mobile but physically demanding and low-paid. According to Ruslan, collecting cardboard or metal often requires more effort and time than it actually earns.

“I don’t do it anymore—I realised it’s not worth it. At best, when I collected cardboard, I’d make about fifty hryvnias. More struggle than profit. Then I switched to cans—some acquaintances were collecting those. To make a kilo, you need around sixty cans. And they pay twenty hryvnias per kilo… so I gave that up too.”

After years of living rough, Ruslan has come to know what he calls a “survival map”—the places where you can find what you need in rubbish bins: food, clothes, or items that can be sold at makeshift markets or flea stalls. These days, he also knows the people who are ready to buy what he finds. This knowledge has become a vital resource in his struggle to survive.

“The best area is at Chudo-Horod [a local residential complex],” he says. “You can pick up all sorts there—clothes, bed sheets, mattresses, phones, chargers, power banks—I’ve got it all covered now. At the beginning I was clueless; I didn’t know who to offload things to, even when I did find something decent. But now I do. The only thing that gets in the way sometimes is the number of people doing the same. Everyone’s looking for something—some for food, some for phones, others for clothes.”

Another man we spoke to, Serhii, said that in the world of scavenging, connections are everything. He has built up a relationship with a local supermarket, where the administrator calls him whenever expired goods are being cleared out. Serhii buys the items for a pittance and then resells them to local street traders—known as “baryhy”—who in turn sell them at a steep markup on market stalls.

“He gives me a call—‘Serhii, come over.’ I’ve got my baryhy—I drop the goods off to them and make around 200 to 400 hryvnias, depending on what I’ve got. Happens once or twice a week. There’s meat, fish, sausage, cheese, dairy—all that stuff.”

Most of the time, however, collected items aren’t sold or traded — they’re kept for personal use: eaten or used in daily life. People living on the streets, forced to gather such things, often have to cross internal moral boundaries in order to survive the harsh realities of urban life. Later, they may find themselves having to explain or justify their actions to those they regard as “normal”—all while trying to preserve their dignity.

“Looking for food, looking for clothes… Yeah, sometimes I found things—I had to,” said Sasha. “Times were so tough, I’d reached the end of my rope. I could barely walk anywhere. So if there was a dumpster nearby, I had to dig through it—had to look for something to eat, maybe some clothes.”

That is the reality for many: surviving on what others throw away, even when it brings a sense of shame or inner conflict.

“My friend would dive into the altvater [a bin], I’d stand nearby,” said Nataliia, who had come to several aid distributions. “I’m scared to go in—it feels shameful. People say, ‘You’re young, go get a job.’ So I didn’t do it. She did, yeah.”

Photo: Borys Ukrainskyi

Begging

People experiencing homelessness often beg on the streets due to circumstances that make stable employment and a steady income impossible. Olya, for instance, resorted to begging only when she couldn’t find temporary work:

“It depended on whether there was work or not. If there wasn’t, then yes, I had to, because you want to eat every day.”

For many who live on the streets, begging becomes more than just a means of survival—it develops into a complex system with its own unspoken rules and hierarchy. Olya explained that she often had to share part of her earnings with those who “watch over the spot” in order to be allowed to “work” there without risking harm. Sometimes this also meant giving a share to other homeless people who effectively controlled the territory.

Choosing a location is always a strategic decision—near churches, markets, shopping centres, or tourist streets. At the same time, staying in one place for too long is dangerous: security guards might chase you away, or other “competitors” might push you out. Earnings from begging directly depend on several factors: the season, the day of the week, the city’s general mood, and how many people are out and about. According to Olya, the best times were spring and summer, when more passers-by and tourists are on the streets:

“It’s better in summer—easier, warmer, and more people. Yeah. A lot of tourists come. And basically, people who live on the street make their living off of them.”

Tamara, who stays temporarily in a women’s shelter during the winter, has often thought about leaving—it’s impossible to earn anything there. The shelter is located outside the city, far from tourist spots, and her only income comes from begging. Like Tamara, many people with illnesses or without a profession consciously choose the streets over shelters because there are more opportunities to earn and even put something aside.

Access to legal employment remains largely out of reach for homeless people. Age, education, gender barriers, lack of documents, and stigma all stand in the way. Employers often don’t trust homeless people, see them as unreliable, and won’t give them a chance to prove themselves. People who have experienced homelessness say they feel they must “earn an employer’s trust” and make an extra effort—that they need to be treated differently, for “obvious reasons.”

No Shelter: How the War Affects the Homeless

People without housing are among the most vulnerable to the direct threats of war—shelling, injuries from shrapnel, and blast waves. During air raid alerts, most remain out in the open. Almost no one goes down into shelters—either because there are none nearby, or because they are turned away. Some people experiencing homelessness say they were forced out of shelters due to their smell or appearance. Others say they’ve long stopped being afraid: some have grown used to it, while others no longer see the point in hiding.

With no protection from the state or from family, people on the street are left to face danger entirely on their own. In the absence of any safety net, many turn to God or a higher power as their only source of psychological support.

“Where it catches you—there it catches you. A shelter can collapse… you might already be dead by the time they dig you out. But out on the street… well, the blast wave might throw you clear, if anything. There was a strike recently, near the Musical Comedy Theatre—fifteen people were killed. Doesn’t matter to me. I sleep the same way I always have. I don’t react anymore. I’m not afraid. We all walk before God, and however long God has given you to live, that’s how long you’ll live,” said our friend Zhora, who moved to Odesa from Zakarpattia.

Tamara agrees, adding that she, too, believes it is God who keeps her alive:

“The drones were firing. But if something’s been given to you by God—there’s no escaping it. If it’s your time to die, then you’ll die. What’s the point of being afraid? I believe God is protecting me. If I’ve been out on the street and nothing has fallen on my head, then it means God loves me—it means He still wants me here.”

Photo: Borys Ukrainskyi

Beyond the immediate threat to life, the war has significantly worsened an already difficult economic situation. As mentioned earlier, opportunities for casual or temporary work have shrunk considerably, prices have surged, and access to housing has become even more limited.

“Before the war—yes, things were easier. There was work, there was stability. Even though I was already on the street back then, you could still find small jobs,” says Svitlana, who has lived in Odesa for more than twenty years. “Now it’s harder. There are fewer people, less waste, and far less humanitarian aid.”

Originally from Vinnytsia region, Svitlana often jokes and does her best to avoid conflict. She says she’s never made any enemies. At the time of the interview, she had recently left a rehabilitation centre, where she spent three months sober—free from alcohol and drugs. Asked about the personal impact of the war, she answers:

“[At the beginning of the war] we went to sell paper [recyclables]—turned out, the price of paper dropped by half, and vodka doubled. So we basically got screwed four times over.”

But it’s clear that the war has had a far deeper impact on Svitlana. Her son-in-law is currently fighting on the front line, and several of her acquaintances in the military have been killed. She also recalls that homeless people she knew began disappearing without a trace—only for it to later emerge that they had been forcibly conscripted off the streets.

“One guy—they took him right after work [referring to unpaid labour at the rehabilitation centre]. He said he wouldn’t hide from the army. He went, and a grenade exploded in his hands… And since they took him directly from the centre, they later called the supervisor there and said, ‘He’s dead. Do you know if he had any relatives?’ But nobody knew of any… He was on the front line for about two weeks before he died.”

Ruslan also shared his experiences with representatives of the Territorial Recruitment Centers (TRCs), shedding light on the specific challenges faced by homeless individuals during mobilisation. Lacking a fixed address, official documents, or access to basic resources, they are significantly more vulnerable than the average citizen.

“This happened to me twice… I ran from them [TRC officers], and the police were after me as well. I kept telling them, ‘Guys, I’m not going anywhere with you.’ But they just wouldn’t listen. I told them, ‘I don’t have any documents, I’ve got absolutely nothing—I live on the street.’ They decided to take advantage of that. ‘Oh, you’ll have a new home now,’ they said. And I said, ‘What new home?’”

Ruslan speaks openly about his fear of going to war—not out of indifference, but out of deep anxiety about what might happen to him afterwards. He’s afraid that once the war is over, he’ll find himself in an even more desperate situation—unable to work or earn even a minimal living through odd jobs.

“If I come back with no arm or leg— is the government going to pay me for that? That’s the only reason I don’t want to go. What am I supposed to do then—sit outside Pryvoz with my hand out?”

He talks about several homeless acquaintances who returned from the war with significant savings—only to burn through the money quickly and end up back on the street. Despite serious injuries and post-traumatic stress disorder, some of them chose to return to the front line simply to earn enough to afford rent again. Meanwhile, another man he knows—once homeless and now a veteran—had to spend months in court fighting for official combatant status and the compensation owed to him for his injuries. These stories reflect the deep challenges of social reintegration and the lack of proper state support for veterans without permanent housing.

Photo: Borys Ukrainskyi

Identity

The word “homeless”—or the familiar abbreviation that long ago became a slur—often sounds more like an insult than a simple description to many people living on the streets. They avoid the term, distance themselves from it, and prefer to use other words. In the public imagination, “homeless” doesn’t just mean someone without a roof over their head. The term is so deeply stigmatised that it has lost its neutrality and become a kind of branding—a mark of social disgrace.

People living rough often distance themselves even from one another. Just as in wider society, hierarchies exist within their own circles—shaped by how they perceive themselves and others. Some try to hold on to a sense of dignity, seeing themselves as “different,” even “better” than those they view as “addicts” or “criminals.” This distancing becomes a kind of defence mechanism—a way to resist fully slipping into the role society assigns them.

Olya, when recalling her past odd jobs, often emphasised not only how hard she worked, but that she never stole from anyone—unlike some of her acquaintances.

“I cleaned apartments, and the gold, dollars, and euros were always left behind. Back then, there were no cameras yet—they just came to check. They’d return home, and everything was neatly in its place. What’s the point of stealing, only to have to run from you and others later? You pay me for my work—that’s enough for me. Because nowadays, you can’t build anything on someone else’s loss.”

She accepts her situation and the system’s rules: she does not complain, but rather tries to prove that she is trustworthy and not a threat—that she is “a woman, not a castoff.”

“You walk around, people always see you everywhere. If you’re not ‘normal,’ they won’t let you in anywhere. They always judge how you look. The most important things are long hair, cleanliness, neatness, and your manners—that’s everything.”

Olya points out that surviving on the street is like constantly going through an “interview for dignity.” She believes that to have a right to housing, work, and basic assistance, you have to be “worthy” of all this—constantly demonstrating your virtues and meeting expectations. Her experience highlights a much broader problem of inequality and exclusion: the most vulnerable are forced to struggle not only with life’s hardships but also with societal prejudice and distrust.

Shame is one of the most powerful and still least visible emotions in the experience of homelessness. For many, living on the streets is not just about poverty or losing a home; it is, above all, about a deep sense of personal guilt and failure. For Ruslan, shame is a key emotion that keeps him from returning to his family.

“I can’t go home simply because, well, I lied—said I had a decent amount of money saved. But going home? I’m ashamed. Ashamed just because I said I had a reasonable sum… Yes, I’d come back dressed smartly, but with only five or ten thousand in my pocket. They’d say, ‘You’re a liar,’ and that’s all.”

People rarely blame the system or their circumstances for their situation—instead, they take full responsibility for themselves and their decisions. The fact that society tolerates homelessness is overlooked; therefore, anger, shame and disappointment are usually turned inward. In reality, without support, even a single mistake can have irreversible consequences. What is simply life experience for someone with resources can become a “breaking point” for a vulnerable person struggling to survive.

During the conversation, Olya revealed an inner conflict: on the one hand, she had internalised the stigma that homelessness results from “bad behaviour,” but on the other, she was gradually coming to realise the injustice of the circumstances she found herself in.

“Anyone can end up on the street if they behave badly.”

“Did you ever behave badly?”

“No. I behaved normally. It’s just that my mother didn’t want me back then, when I was a child. That was her decision. The apartment was hers.”

Life without a roof over one’s head is a daily struggle for survival and dignity. The war has only intensified the problem of homelessness, stripping many of their last remaining resources. But behind every one of these stories are not just abstract statistics, but real people who need not only sympathy but concrete support. To change the situation, a comprehensive systemic policy is required. This includes creating affordable social housing, expanding access to medical and psychological care, social reintegration programmes, employment opportunities, and legal protection. It is also vital to tackle stigma—because as long as society continues to view homeless people as “others,” the prospects for justice and equality remain slim.