I met Dianne Feeley in front of Ivan Franko National University of Lviv on 7th of March. There she had to meet — at the invitation of the independent student union — with the students and discuss reproductive rights in the US. I said hello and while shaking her hand I thought to myself surprisedly: how vigorous and enthusiastic this woman is in her venerable age. Much more vibrant than I am.

A few days before that, Dianne visited Kyiv where she lectured on the similar topic. Then she went to Kryvyi Rih and met with trade unionists, students and volunteers. Dianne did not talk much, but instead she emphatically asked. ‘I was in Kryvyi Rih, a working-class town. They invited me to the English class at school where students were prepared to ask me questions, so I decided instead to ask them.’ After the slew of meetings and the shelling of the town overnight, Dianne took the train and made it to Lviv.

We spent several days together and talked a lot. On 8 March, the International Women's Day, we took part in two demonstrations together – the Rights Instead of Flowers action and the march of military wives and children for clear terms of service. Later, Diana shared her impressions: ‘Both demonstrations were wonderful. […] In the United States, we don't have a tradition of International Women's Day, although it comes from the experience of American women workers in the early twentieth century.’

In that noisy and enthusiastic atmosphere, Dianne was constantly surrounded by people who were interested in where she came from, what she did, and what her impressions were. And when the participants learned more about her life, the conversations dragged on for a long time. This is not surprising, because Dianne had a lot to share.

Dianne Feeley's experience in the feminist and labour movements spans more than half a century. She was a participant in the civil rights movement in the United States, an activist in the movement to end the war in Vietnam, a member of student strikes, and a union organiser in car factories, where she worked for many years. Even today, in retirement, Dianne goes on fighting: she is the editor of the socialist magazine Against the Current and is involved in grassroots campaigns to protect migrants in the US, especially after Donald Trump's victory in the 2025 election.

Before Dianne's departure back to the US, we spoke with her to record her experiences of years of struggle and her thoughts. And most importantly, to reflect on what lessons from her life path could help us in our struggle for equality and justice in these obscure times.

***

Maksym Shumakov: Could you please tell us about your activism in the labor and feminist movements? How it began and what were the important milestones for you there?

Dianne Feeley: I’ve been in activism since the 1960s, so it is a long period of time. And my feminism really came out of my involvement in the civil rights movement which was the struggle to end Jim Crow laws in the South which was a very strictly segregated system. But also in the North where I grew up. We also had a less violent form of segregation. And so there were many fights around desegregating schools, housing, unions… So that is one whole area.

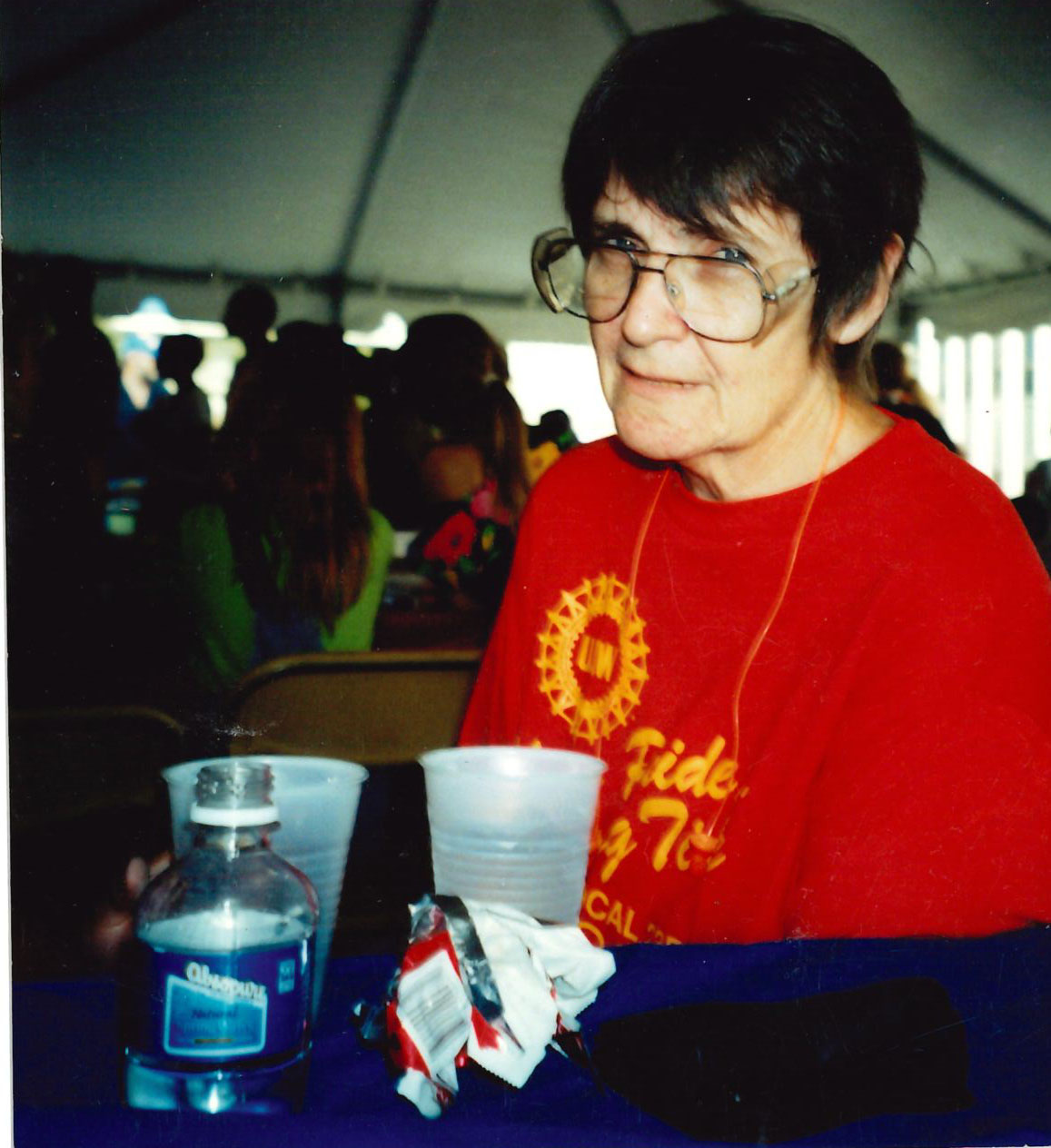

Dianne Feeley in Lviv

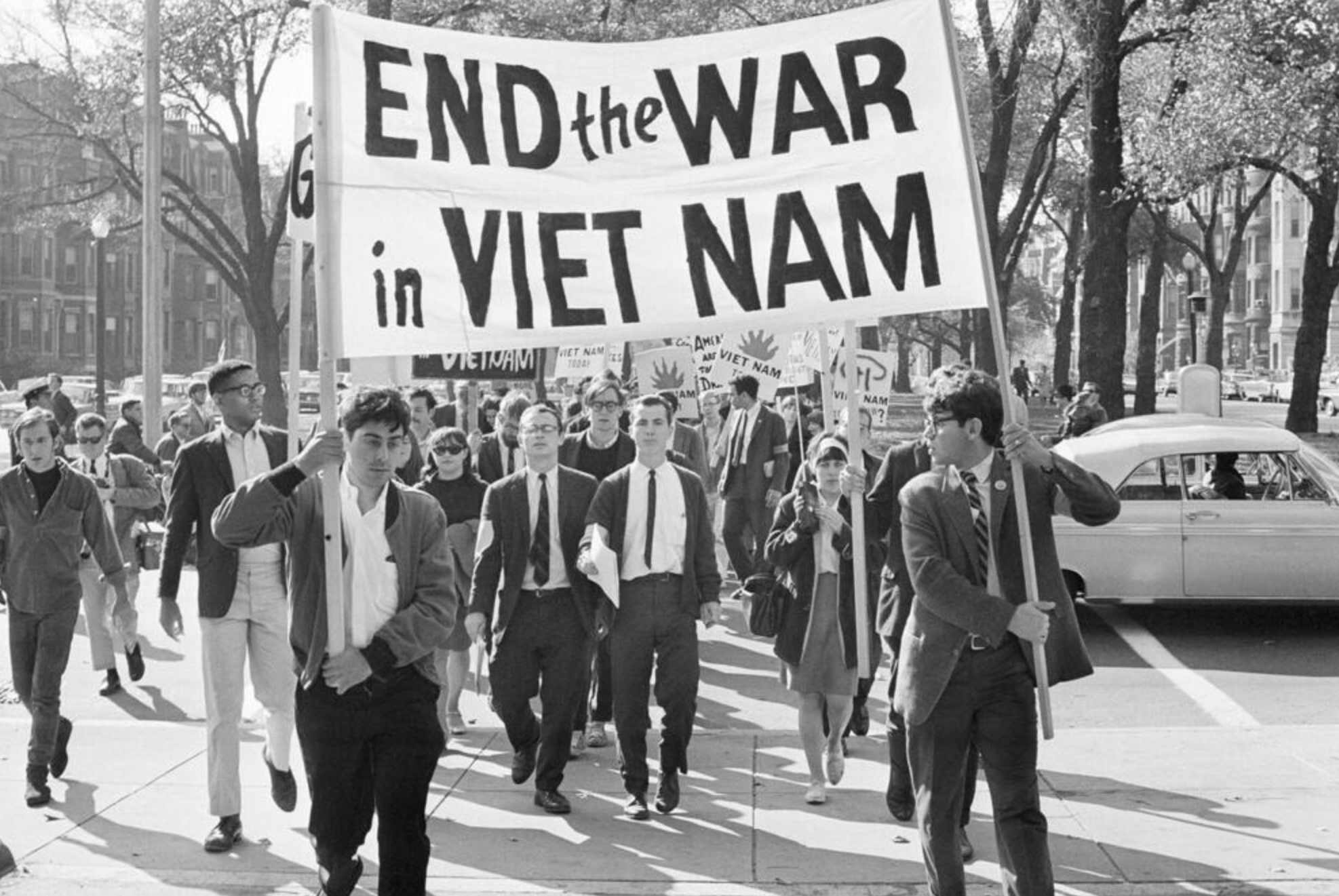

And the second area was the war in Vietnam. I became an anti-war activist. There were a number of slogans and a number of political organisations that put forward ideas on what should happen. The Communist Party had the slogan ‘Negotiate now!’ and the Socialist Workers Party demanded ‘Troops home now!’. I was very much attracted to the latter, to the idea that the people who are fighting the war are the ones who can withdraw their labor power and the war will end.

My own brother was in the navy at this time. His only alternative to the draft had been to flee to Canada or go to prison. Because of the draft he was gonna to go to the war. To reach soldiers we had to talk with them, and give them leaflets about why they should oppose the war. When I was office manager to the G.I. Civilian March for Peace in 1968 there was a group who came to the office after work and then went out leafleting. They were Marines, the military division portrayed as the gung ho guys that were the first sent in to the front. I asked them, “Well, why are you so eager to leaflet against the war?” They replied, “You don't know what we do”. Their job, working on Treasure Island in the San Francisco Bay, unloading bodies coming back from Vietnam day after day. Psychologically it was a rough job. It convinced them to oppose the war.

We began to hear of situations where the troops in Vietnam would confront their order and announce, “Sergeant, we don't want to go out, we're voting against going out on patrol tonight”. The army was falling apart; they had to withdraw. The two reasons the U.S. war in Vietnam ended were the determination of the Vietnamese combined with an increasing number of U.S. soldiers not willing to fight and die there.

Student protest against the Vietnam War, October 1965. Photo: Beta / AP

What struck me as a young person was that we can change things. Even if our government wants to pursue a war, we come together and develop a strategy that can successfully oppose them. That was an important lesson: a minority can become the majority.

It is out of those experiences that I became a feminist. That is not just in general being against injustice, but seeing the particular injustice of myself as a woman who cannot be equal to men. “It's okay for you to be here, but please sit down and don't bother us” viewpoint. Women have always been leaders in the civil rights movement (Ella Baker and Rosa Parks are very well known), but they were backed by a whole group of women. They were not just extraordinary stars but women who had a base. And the same thing is true in the Vietnam antiwar movement. We were second wave feminists. The earlier wave (1840s-1860s) was when women became involved in the abolitionist movement – the fight to end slavery – but they had few legal or political rights that even working-class men had.

Both times the feminist movement arose out of our involvement in the civil rights and antiwar movement. That gave us the strength, the confidence and the organizing abilities to raise our own particular issues. Of course there’s a whole range of feminist issues, certainly the right to control our own bodies, with abortion and birth control and the fight against sterilization abuse, which occurs especially among women of color. But also the fight against violence, both in the home (where a majority of violence occurs) and in the workplace. Feminists have taken up the notion that jobs are naturally gendered. If there’s work that needs to be done, we are capable of doing it. We don’t want to be harassed or demeaned as we do it either by our co-workers or by our bosses. So all of that has contributed to the vitality of a feminist movement.

Women have always been leaders in the civil rights movement (Ella Baker and Rosa Parks are very well known), but they were backed by a whole group of women.

You’ve mentioned that that was the time when you realized that you and your comrades could change something, could affect the state of affairs. From that followed a slew of resolved actions like leafleting the soldiers and persuading them not to go to the war. In our time this is something complicated to imagine. For example, if in Russia some groups of activists decided to spread anti-war materials among the soldiers they would likely be arrested. So my question is whether there was any reaction from the state then e.g. repressions, censorship etc?

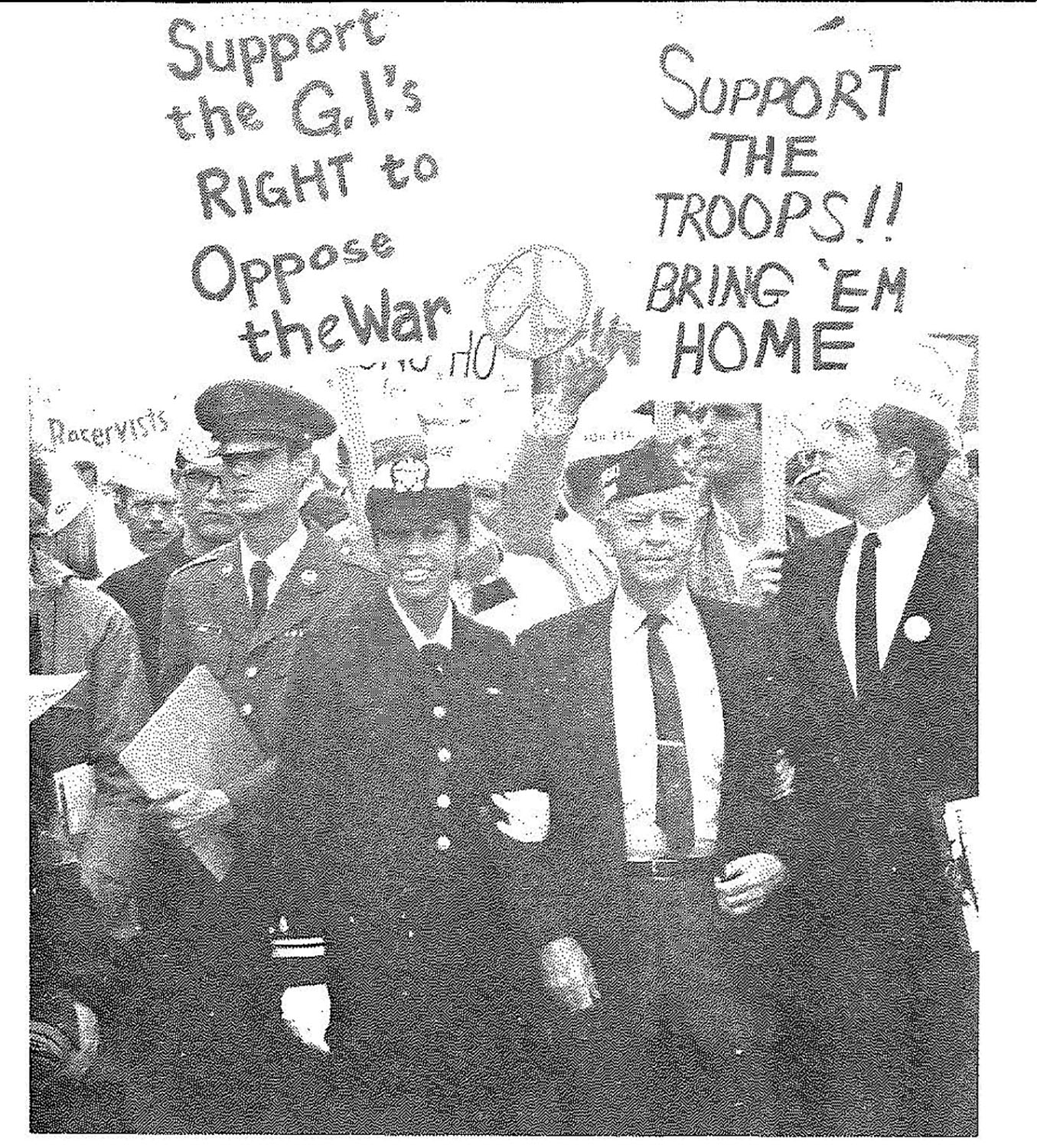

Yes, there was repression, but that didn’t stop us. For instance, in the G.I. Civilian March for Peace, 500 soldiers marched at the beginning of the parade, some in their uniforms. Many were sent to other bases and some were disciplined. Both Airman Michael Locks and Lieutenant Susan Schnall, a Navy nurse, were sentenced to a year in prison and dismissed from the military.

GI-Civilian March for Peace. These include leaqders of the GI-Civilian March for Peace, October 12, 1968. Airman First Class Michael Locks and Navy Lt. Susan Schnall (two on the left) were sentenced on a year in prison for wearing their uniforms to the march. Schnall is active today in Veterans for Peace (she is president the VFP Board of Directors). Man to left of Schnall is retired General Hugh Hester, who spoke at the march. Photo courtesy of Dianne Feeley

We went to the military bases where the soldiers were while the military brass tried to keep us out. We had to sneak in different ways, and we got thrown out in different ways. But as we were building toward antiwar demonstrations in the fall of 1968 it became harder to get on the bases were closed. Schnall and her husband had a friend who had a helicopter. We printed up 20,000 small-sized leaflets, and distributed them from the plane. That was really great, because the servicemen were grabbing the leaflets right from the air. And the incident was on the front pages of the newspapers. There were different cat and mouse games that we worked out over time..

Soldiers were not just on the bases. For example, a lot of G.I.s were at the San Francisco airport as they were going to Vietnam or coming back. It was there that I first heard a G.I. saying that soldiers were voting about whether to go out on patrol. At first I thought, “Oh, they’re just kidding me”. But then I realized, “The Army is falling apart now”.

There was also repression on the campuses (but I think it is greater today than it was then). I was involved in the San Francisco State student strike (1968-69), which I think is still the longest student strike in U.S. history. It went from November to about March or April. Over 750 of us were arrested and expelled.

Our strike had 15 demands. Most of them were around issues of Black, Latino and Asian programs. We demanded a school of Ethnic Studies so people could learn real histories, rather than just the tale of how the colonists came west, settled everything and all the Indians disappeared. So much of American history perpetuates the myth of “Manifest Destiny”. Another demand was to rescind the firing of George Murray, who was a member of the Black Panther Party. Another demand was to kick ROTC (Reserve Officers' Training Corps) off campus, which was a program of military training. So the strike combined a number of issues.

We lost the strike in the sense that so many of us were arrested and expelled, but they were forced to implement some of the demands, including setting up the School of Ethnic Studies, which is the only U.S. campus that has such a school. It has something like 60 professors, covering a wide range of ethnic communities. Today the San Francisco State University says, “Oh, we are great. We have this great School of Ethnic Studies, come here and study with us”. Periodically they send those of us who were expelled letters inviting us to come and celebrate some anniversary. But this unique program was the result of our struggle, and was fiercely opposed by the administration at the time. The administration allowed police on our campus, and there was even one incident where a cop shot his gun. Other campuses saw repression and some students, at three different campuses were killed (Orangeburg, South Carolina, Jackson State, Mississippi and Kent State in Ohio).

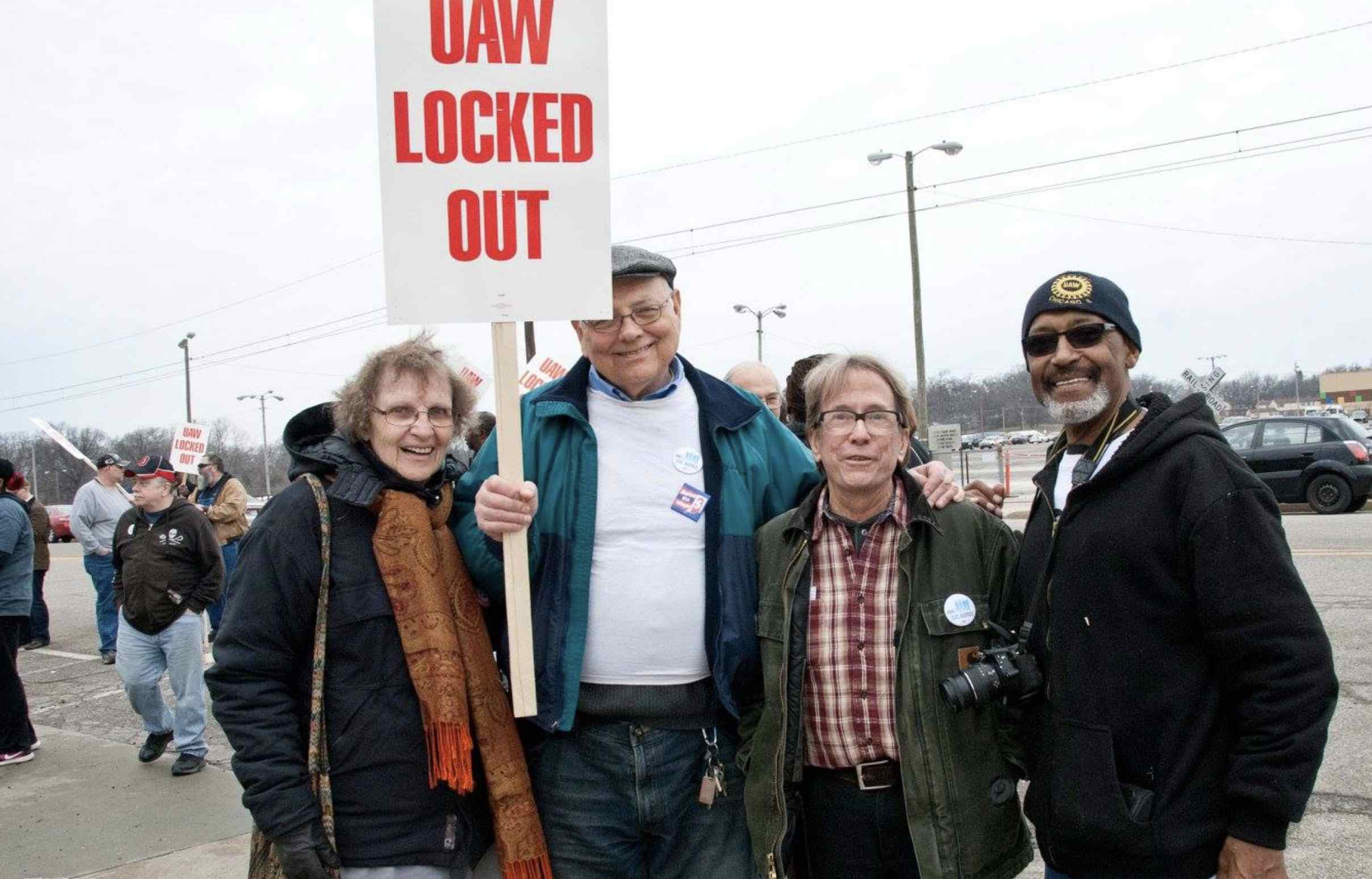

This is Danny Glover, the Hollywood actor, who was an activist at San Francisco State and a striker during 1968-69. We are talking at a UAW rally in Hamtramck around 2009. Photo courtesy of Dianne Feeley

I guess this experience of student struggle came in handy for you later on while working at the factory and organizing unions. Didn’t it?

Over the course of my years as a worker, trying to be in a union, to start a union, or to join the union that existed in my workplace, I was trying to bring a sense that if we work together, we can change the situation. It could be around wages or, more importantly, around working conditions or larger social issues.

The union can't just be concerned with wages and even bettering the conditions at the workplace, but what is its role in the larger society. The unions’ concerns should include for instance, the questions ranging from toxic waste to the quality and quantity of childcare centers. It seems to me, the feminist approach, or an eco-socialist approach, is important in bringing a real sense of how working people can change things.

I always tried to do that at my workplace. Usually it was around a particular campaign. For example, when I first started working at a Ford plant in New Jersey I had been active in trying to get the Equal Rights Amendment into the federal constitution. I had talked with women's groups, helped to organize demonstrations and even debated rightwingers such as Phyllis Schlafly. Suddenly 90% of the workers in my plant were men. I had to rethink how I presented my arguments, because I'm trying to win men over to a feminist demand. I wasn’t talking to women about how society viewed us as inferior beings, but to men who had these rights and needed to demonstrate their solidarity. The women’s committee of the union was able to carry out a good campaign but ultimately time ran out and the amendment didn’t pass. And we still don’t have a federal ERA.

The union can't just be concerned with wages and even bettering the conditions at the workplace, but what is its role in the larger society.

Although the contexts of today and that of the 60s and the 70s are very different, do you think there are lessons that could be drawn from these past struggles including anti-war movement etc?

Yesterday I read about a Russian man arrested for writing on a wall “I don't want to get used to being at war.” Despite a very high level of repression in Russia today, some people are protesting injustice. It may not be enough, it may not be coordinated, but I'm sure it's having an impact. People are noticing and talking, maybe not so openly, but they're talking to their friends or their co-workers at some level. So I think you do what you can, and then maybe there will be a breakthrough.

Yes, I think there are lessons from the past, but there are also new circumstances. I'm really shocked at how much more repressive the universities are today, even under Biden. The students are being expelled from school and professors are being fired, even without due process.

So it's much more intense than it was. A main issue today is supporting Palestine and demanding that the university withdraw its funding from Israel or from a company that supports or sends materials to Israel.

Furthermore, DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion), is a program that many universities and corporations set up as affirmative action was basically outlawed in the United States. DEI tries to reach out to people of color who have suffered from racial prejudice, especially those who attended inferior and segregated schools, and provide them with the aid they need to succeed. This is seen as valuable not just for the individual, but for having a more diverse society. The University of Michigan, for example, has a number of distinguished professors today who were nurtured by that program. But the right wing wants to destroy the program in the name of “merit”. The Trump administration claims it is discriminatory and wasteful.

Moreover the methods that have been employed against those who support Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against Israel for its continual war against Palestinians include not only suspending or expelling students, but bringing them up on criminal charges. The University of Michigan — which is 45 minutes from where I live — has charged students and community members with felonies! When they couldn't get the local city attorney general to bring the charges, they demanded Michigan’s attorney general of state of Michigan file charges. You can see how political it all is! The greater repression today is similar to the witch hunt that existed in the post-World War II period we call McCarthyism. There's a desire to make people fearful of their jobs or future employment possibilities.

The world is divided right now into those who see the world as a dog eat dog society. There is no community, only the isolated individual or family. You can't support immigrants, because immigrants will take the food out of your children's mouths. In this individualistic society helping other people is an unacceptable cost. Vance, the Vice President, says, “Well, you can help your family. Maybe you can help your neighborhood, maybe you can help your community, but you certainly can't help anyone beyond that.”

That's one side, and then the other side is what we represent. What we're saying is we're for solidarity. We understand that everyone is a human being, entitled to a certain standard of life that makes it possible for people to not only survive, but to flourish. And to do that, we need to be able to treat each other justly. No one should be a billionaire with the capacity to dictate policy.

In Flint, during a 1997 strike, with other members from my union local. Photo courtesy of Dianne Feeley

This sense of solidarity can be seen right now in people's willingness to defy what the Trump administration’s plans. The official Trump regime wants to get rid of 11 million immigrants who don't have the proper papers. Some people get confused about that. They think that we should get rid of the criminals, but who is a criminal? Trump criminalizes all those whose parents were not U.S. citizens. In my country there are categories of people who have a certain status that enables them to live and work here. For example there are about 270,000 Ukrainians who have Temporary Protected Status. People from 16 different countries have this particular status, granted to those whose country is suffering from war or climate catastrophe, and renewed every 12-18 months. The president is in charge of it and now Trump is threatening to end the program for all Ukrainians. That would mean those 270,000 Ukrainians who yesterday had the right to live and work in the United States would lose their status and become illegal. Trump has signaled that he is ending the status for Haitians.

The official Trump regime wants to get rid of 11 million immigrants who don't have the proper papers. Some people get confused about that. They think that we should get rid of the criminals, but who is a criminal?

For someone like me from the Ukrainian perspective it seems like there is no grassroot movement in the U.S. opposing the far-right Trump administration and its repressive initiatives. All that is seen are the dissents and concerns of European and other politicians around policies thereof. I wonder whether there are grassroots acts of defiance and of solidarity and if so, could they spur a new movement?

Trump is not the first person who has been deporting people and overlooking their right to asylum. Actually, the same was true under Biden and Obama. The movement dubbed Obama Deporter-in-Chief because he deported so many people. Trump's calling immigrants criminals also has evil people like Stephen Miller plotting the deportation process. This has expanded the grassroots movement that already exists.

Especially during Obama's administration, the movement responded by having cities, counties, unions and other institutions pass laws that protected people, by preventing local policy from providing information to ICE (the immigration authority). We have “safe cities” with non-cooperation protocols.

I gave a class before I came to Ukraine, to working people whether they belonged to unions at their workplace or not. The law says that ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) can come and detain anyone without proper identification in a public space. Well, what's a public space? It might be the store, but it's not behind the counter, it's not in the office, it's not on the factory floor. Your boss should be sure to know that. And even if the immigration has the proper signed warrant from the judge, it must name the person they want? But nobody has to say, “Oh, there's Joe Gonzalez. Take him”. No, they don't have to say anything. So there are ways that we protect our co-workers.

At an event in front of the American Axle & Manufacturing plant where I worked in Detroit, around 2000. Photo courtesy of Dianne Feeley

We also give out a leaflet that says, if you're in your home and you're undocumented, here are things that you should know you can do, and we will try to protect you. Many mutual aid groups are developing. If people don’t feel safe walking or driving, or picking up their children from school, immigration can find and snatch them. We can bring them food or help their children go to school. Right now people are afraid to leave their homes. So we try to minimize their need to go out.

Immigration tries to target areas where parents might be coming to pick up their children – schools, parks, hockey games. Most school systems I know about will not allow ICE to come into the school to look for anyone. A friend of mine teaches at a Chicago school where both the city and the school district have adopted “safe” protocols. Yet she was constantly being asked by the students, “What's going to happen if ICE comes?” She kept replying that they're not going to come, “We will not allow them to come.” When they kept asking, she finally said, “If they come, I'll punch them in the face”. The kids found that the perfect answer and settled down.

Trump wants to go after Chicago, because it is a safe city. He wants to block their access to money and find other ways of forcing them to comply. Because Trump is a bully who wants to criminalize and remove immigrants, he silence those who stay in his way. So cities like Chicago and Los Angeles are first up.

But of course, Trump's policies are very contradictory. In fact, the U.S. needs immigrants as a part of the workforce. In my neighborhood — which is mainly a Mexican American neighborhood — by five o'clock in the morning, everybody's gone off to work. And 80% to 90% of all the people without papers are working and that’s true for those with temporary status such as TPS – in agriculture, food processing, health care, janitorial services, manufacturing and many other jobs.

Trump is moving on every front. Shock and Awe is his mantra. But it seems to me that fighting back around immigration is a key fight along with supporting public sector workers who are being terminated. Public sector workers are also demonized, not as rapists and terrorists but as people who don’t do a hard day’s work. The Trump team is attacking public sector workers because a high percentage of them are in unions. There's more public sector workers organized into unions than private sector workers. Therefore if he can destroy their rights that'd be a big plus for the corporations and a drastic change in the political climate.

Thank you for sharing your experience. In conclusion, I am very interested in what drives activists in times of ups and downs, twists and turns, what forces them to continue and do not stop even in dark times like ours., do not stop. So I'd love to ask you, as a person who has been an activist for more than fifty years, what drives you to continue this whole fight?

Well, I don't know: it seems like there's always work to do. And of course, it's great when the wind is with you and you can move ahead. When I was young, I thought we would be a lot further along than we are today. This is a very dark time. But the basic reason that I started to fight around social issues was because I was against inequality. It seemed terrible to me that some people have limited opportunities while others have so many resources. I’ve always been concerned about having a better situation for all of us, not just me. When I leave my job, I want to leave it in a better space than it was when I came. I think that desire to make change for yourself, for your family and for your community — and even for the next generation or beyond — is what drives me.

This is from a 2009 solidarity rally in South Bend, Indiana while UAW workers were locked out. Photo courtesy of Dianne Feeley

But part of being a socialist is that you're an organizer, so you can't do it all yourself. You realize that you can only be effective if you're part of something larger. So you're constantly trying to think of — okay, how can I bring new people into the movement and help them have experiences so that they feel that they can do something? For example, around immigration, I'm working with a young African American guy who has never had any kind of political experience. He's very excited about doing this work, but he thinks he has to do it all himself. When we gathered a long list of people he told me he had a lot of work to do because he wanted to call everyone. I asked him, “Isn't there somebody else on the committee who could help with that?” We need to involve others, to make that circle bigger. And if you drop dead tomorrow, there's going to be somebody who will know how to continue.

When I first got politically active, I thought, “I'll do this for five or 10 years, and then there'll be the revolution, and after that I will be writing my novel. Later I realized, no, this is not going to be. Forget about the novel. The work is certainly interesting. In a social movement you get a lot of positive feedback, because what you're doing is building community and trying to end inequality — it is something that is indeed valuable.