Maksym Kazakov

Ukraine’s mining and metal industry was constructed largely in the era of fulfilled (and over-fulfilled) five-year plans. After Ukraine gained independence in 1991, these factories and mines played (and continue to play) no less a role than in the Soviet state. Today, every school student in Ukraine has to know about the shortcomings of the planned economy for their final exams. But after the transition to the market economy, these shortcomings became, if anything, more pronounced: throughout the 1990s, the share of ferrous metal production in Ukraine’s GDP grew thanks to loss of mechanical engineering and other branches of the country’s economy that produced goods with a high additional value (Popovych 2013).

By the early 2000s, steel exports had become one of the main sources of income for the state budget and renewing Ukraine’s economy. Steelworkers could thus claim proudly that they were the ones responsible for bringing in the largest amounts of foreign currency, although the core of the 2000s boom also contained the factors that after 2008 would provoke crisis after crisis both in Ukraine’s economy and political sphere — the strong dependency on the global economy and concentration of profitable enterprises in only a few of the country’s regions (Bojcun 2013). In recent years, the mining and metal complex has been seized by less than positive processes, with the loss of mines and factories in Ukraine’s uncontrolled territories. At the same time, the proportion of complex production (cast iron, steel, prefabricated construction materials) within the production cycle has decreased while iron ore exports have risen (Kravchuk, Prokhorenko 2016).

"Today, Kryvyi Rih workers are involved in a struggle that could have far-reaching consequences for the whole of Ukraine."

These tendencies are hardly positive, but despite all its problems, metal production remains a central pillar of Ukraine’s economy. Even in the crisis year of 2015, it guaranteed nearly a sixth of industrial production, a quarter of goods exports and 1.5% of jobs (Amosha, Buleyev, Zemlyakin 2017: 61-62). This last figure might not seem impressive at first glance, but metal workers are one of the best organised, conscious and active parts of Ukraine’s working class. The fact that so many jobs are concentrated at large plants, which gives a sense of a working collective; involvement in complex production processes, which raises the veil masking the “secrets” of the economy; the tradition of independent trade union movements, which began at the end of the 1980s — all of this creates a situation in which workers can act independently and achieve certain results. A situation that is far from typical for most other sectors of Ukraine’s economy.

The longest city’s largest factory

From this point of view, the metal workers and miners of Kryvyi Rih particularly stand out. We can assume that the size of the city plays to Kryvyi Rih workers’ advantage. But it’s not the (famous) length of the city that’s important here. Kryvyi Rih, on the one hand, isn’t an regional centre, overfilled with authorities and businessmen, who suppress any manifestation of independent activity from the lower classes. On the other, in terms of size, the heart of the Kryvbas mining basin significantly outclasses your standard provincial monocity in Ukraine, where the factory management disciplines workers with ease. In other words, while in cities like Dnipro or Alchevsk, the balance of power is such that independent trade unions are either absent or barely survive, in Kryvyi Rih workers fight off attacks and are even able to organise counter-attacks. This “economic geography” is to Kryvyi Rih workers’ advantage, although this is only a favourable condition that real people draw on in their everyday struggle.

For Kryvbas — and Ukraine in general — the post-Maidan years have been incredibly difficult. The war has broken production and trade chains, sending some workers to the front, and others – in search of work. In 2014, the national currency declined in value three times, though price fluctuations on the external markets have been far more modest. This has created a “paradox”, perfectly logical for capitalist relations: if after the 2015 collapse, prices for Ukrainian metals have already managed to rise again, then real wages have remained lower than their pre-war level. In 2013, the average wage at the country’s biggest metallurgical plant ArcelorMittal-Kryvyi Rih (AMKR) was 5,808 hryvnia (€534), then in 2017 it was 10,278 hryvnia (€306).

The crisis and war have intensified a long-term tendency. While over 2010-2018, AMKR began bringing its owners three times more in pure profit, this same period saw the share of the wage fund drop from 11.3% to 5% of the cost of production. There have been constant cuts to staff numbers — from 65,000 workers in 2005 to 23,000 today. In reality, this “optimisation” has meant the greater exploitation of those who stayed working at the factory, reducing the amount the factory spends on its employees after outsourcing their jobs, the lack of state programmes to help people, forced out of their jobs by automation of the production process, re-train for other jobs. The situation has been similar at other factories and mines in Kryvbas.

2017: Kryvyi Rih rises up

Kryvyi Rih workers eventually gave their answer to the actions of their plants’ owners. In May 2017, coordinated protest actions took place at the city’s main plants (Kryvyi Rih Iron Ore Plant, Evraz-Sukha Balka and AMKR) — employees stopped work, held public meetings, occupied administration offices. It was here that the demand for a monthly wage of 1,000 USD/Euros was first expressed publicly. In today’s Ukraine, this sounded like far too much, but until 2014 a range of specialist workers in Kryvyi Rih did receive this wage. The plant owners constantly refer to average wages in Ukraine, yet workers, via contacts in international trade union organisations, know that even in Kazakhstan, where protests broke out among workers at an ArcelorMittal plant at Temirtau in December 2017, metal workers receive more (€386 in 2017). In comparison with metal workers in developed countries, Ukrainians receive 20 times less — and this is one of the lowest wages across the global industry.

The scale and coordination of workers’ actions made the owners and managers receptive surprisingly quickly. The conflict stopped after an agreement was reached to gradually raise wages (on average by 50%).

Moloch demands his victims

For the owners of Kryvyi Rih enterprises, however, this move did not mean recognising that the workers, or the economic rationality of their demands, were “right”, but merely marked a lost battle in an ongoing war. The owners postponed and rewrote the promised wage hikes in their favour and increased the pressure on independent union activists. At the same time, they began playing the role of the “good boss” who gives workers crumbs from his table, but doesn’t let irresponsible troublemakers “bite the hand that feeds” and bring down the enterprise with their unreasonable demands.

The aftermath of the roof collapse at AMKR on 3-4 March 2018, which killed one employee. Source: Social Movement.

The plant, however, was falling apart by itself — literally. As I stated above, metallurgy remains a source of income for hundreds of thousands of workers, Ukraine’s state budget and big capital. But this industry has terrible health problems: the level of aging of industrial equipment is between 70-80% (Kozenkov, Tsymbalyuk 2013: 2). For workers in Kryvyi Rih, this statistic is a reality: outdated equipment leads to injuries, disabilities and even death.

The Ukrainian government hasn’t only distanced itself from this problem, but is acting in favour of capital, deregulating work safety procedures and reducing the powers of its own oversight agencies. Thus, in 2016, a State Labour Service commission found dozens of violations at AMKR, but in January 2018 a court rejected the demand to temporarily stop work at the plant (a stop costs Kryvyi Rih factories and mines close to $7.5m per day).

On the night of 3-4 March 2018, the roof collapsed at AMKR’s converter shop, killing a 25-year-old worker as a result. To give management their dues, a guilty party was instantly identified — the snow that had broken the roof with its weight. This was a classic Ukrainian force majeure: every year, snowfall in November or March places the whole state apparatus in a difficult position. What could a lone capitalist do in this situation?

2018: the long road to the strike

Workers at AMKR have thus had to resort to more decisive measures. There’s 10 unions operating at the plant, and the largest of them is the Union of Metalworkers and Miners of Ukraine (PMGU), which is part of the Federation of Trade Unions of Ukraine (FPU). PMGU can be considered a so-called “yellow” trade union — an official institution with its roots in the Soviet era, and which mostly avoids conflicts with owners and concentrates on distributing bonuses, sanatorium trips and gifts on public holidays to its members.

Alongside the PMGU, there’s several other independent unions at AMKR. These are the successors of the perestroika-era workers movements of the late 1980s and 1990s, when workers broke out from under Communist Party control and encountered the realities of capitalism. Independent unions have less in terms of physical assets than their counterparts in the FPU, but are prepared for more decisive actions in labour disputes, even real confrontation with management over wages and safety. Many of them are members of the Confederation of Free Trade Unions of Ukraine (KVPU). There’s militant unions at AMKR, which can count thousands of workers among their members. These are branches of national unions (Independent Trade Union of Miners of Ukraine; All-Ukrainian Trade Union of Science, Production and Finance Workers) and regional unions (Kryvyi Rih City Trade Union of Industrial Workers, Regional Trade Union of Working Youth), as well as employee associations operating inside AMKR — Industrial Metal Workers union, the Shield Professional Manufacturing and Transport Trade Union, Independent Trade Union Organisation, Independent Trade Union of Workers. And there’s another “professional” organisation allegedly operating at AMKR, which I will come to in a moment.

The situation at AMKR — accidents ending in fatalities, the management’s sabotage of the 2017 wage agreement and dismissive attitude to worker activists — has convinced both the independent unions and even PMGU of the need for decisive action. On 14 March this year, they held a public rally outside the factory management’s office, where they raised the following demands to the owner and general director: raise the average wage to €1,000, create safe working conditions, stop job cuts and outsourcing, and stop pressuring labour organisations. Over several days, 12,000 employees signed this petition — nearly half of the factory’s personnel.

Alexander Vilkul, Kryvyi Rih parliamentary deputy and co-chairman of Opposition Bloc, calls on workers to support Serhiy Kaplin in the coming elections and attend a parallel workers' conference on 27 March 2018. Source: Social Movement.

But mass protest isn’t only an expression of material discontent, but an opportunity to build political capital — and which instantly attracts specialists of this craft. Serhiy Kaplin, Ukraine’s head “social democrat” and only “left-wing” parliamentary deputy, quickly travelled to Kryvyi Rih for the 14 March meeting. Kaplin’s speech was typical of the current dominant political culture: calls to concentrate on struggling lawfully for European working conditions and lifestyle were heard alongside xenophobic attacks against the “Indian exploiters” (a reference to ArcelorMittal CEO Lakshmi Mittal).

27 March 2018: an employee conference at AMKR. Source: Maksym Kazakov.

For most of the workers present, this nationalism exported from Kyiv was something alien. But the factory management took advantage of this, accusing the trade unionists of playing politics, selling out and xenophobia. Preparations for an employee conference (necessary in order to launch a labour dispute) were held against a background of dirty PR tactics typical of local political campaigns. The AMKR administration even held an “identical” conference at the same time, spreading provocative and defamatory leaflets and newspapers, as well as pressuring workers.

Despite these barriers, the employee conference was held on 27 March, and 300 delegates from all the factory’s shops voted for the demands made at the rally. In their official response, the administration completely ignored the unions’ claims against them, and thus the employees’ authorised representatives voted to start a labour dispute. According to Ukrainian legislation, this means that employees and employer should try to come to an understanding via a reconciliation commission and with the assistance of the National Service of Mediation and Reconciliation — and if where reconciliation is not achieved, then there is the opportunity to start a legal strike.

Black metal, “black” accounts

AMKR workers are well prepared in the nuts and bolts of workplace conflict. For them, it’s essential: at the centre of it there’s the question of wages and their relationship to enterprise income. Even according to official figures, the amount of money that workers have been receiving has dropped year on year.

Anyone interested in Ukraine’s economy is well aware that, alongside its dependence on raw materials (Kravchuk 2018) and aging infrastructure, there is also the key problem of offshore schemes. It’s hard to imagine the scale of what has happened over the past few years. Three quarters of domestic metal exports are processed via foreign middlemen, and this almost always leads to hiding profits offshore in order to reduce the amount of tax paid in Ukraine (transfer pricing).

In the past, workers at AMKR have only mentioned this as a general problem — like any ordinary Ukrainian citizen who rails against “the oligarchs stealing our country” in their kitchen. But thanks to the efforts of left-wing economists Oleksandr Antonyuk and Zakhar Popovych, they can know know the details of these grand schemes. AMKR exports its production to dozens of countries around the world, particularly to Egypt, Turkey, Iraq, China and Lebanon. Trading companies registered in offshore countries act as the middlemen, and they are also part of the transnational corporation ArcelorMittal. Thus, one company belonging to the corporation sells its production via other companies of the same corporation, which are registered outside Ukraine.

Let’s take a concrete case: on 26 September 2017, a consignment of reinforcement steel (one of AMKR’s main export products) was sent to Lebanon through the southern Ukrainian port of Mykolaiv at the price of $324 per tonne. The market price for this product is $510 per tonne. The formal client for this was ArсelorMittal International FZE, which is registered in United Arab Emirates. The difference between the sale price to the trading company and real buyer ($186) goes to the head office of ArcelorMittal in Luxembourg, and is not taxed in Ukraine. AMKR produces 5.4m tonnes of this steel per year, and most of it is exported.

Approximately 50% of AMKR’s production is sold via these schemes, and at least $150 is made on each tonne — this means that nearly $400m is evading both Ukrainian taxes and workers. The current wage fund at AMKR is $85m. And in this light, local workers’ fight at this factory becomes a struggle of national importance — one about channeling incomes to the country’s budget.

A healthy person’s 1st May

After the official start of the labour dispute, the conflict has moved into the stage of drawn-out negotiations, tactical manoeuvres and mobilisation of resources. A public action on 1 May was important in maintaining people’s fighting spirit, overseeing the collective and bringing in new allies, and was organised by the independent unions. Throughout the 20th century, the day of workers’ solidarity has been “digested” by the elites both of bureaucratic socialist and capitalist states. Today, across the world, workers are freeing this holiday and returning it to themselves. The march in Kryvyi Rih was the most important 1st May action in Ukraine this year (the actions in Kyiv, Kharkiv and Dnipro were organised by political parties financed by big capital, and therefore don’t count).

More than 300 factory workers attended the 1st May in the city — the majority of them, although they emphatically supported the start of collective bargaining in March, celebrated a four-day weekend in Soviet style at their allotments and dachas. Their speeches and comments to the media may have lacked the punch of PR professionals, but they demonstrated a clear level of class consciousness. And this is worth noting when Ukrainian society is experiencing extended atomisation, state propaganda aimed at diffusing class identity, celebrating neoliberalism and nationalism, and left-wing intellectual websites, books and journals are operating on a small scale. Here are some quotes from the rally:

“In any case, they [workers who migrate] remain second-class people abroad. We need to fight for a just wage here.”

“Trade unions aren’t about trips to sanatoriums, but defending people and human rights.”

“If the oligarchs don’t offer a compromise after the strike, then we have another option — revolution”

“He [AMKR General Director] says that we aren’t Europeans, that we’re uncivilised. And uncivilised people don’t get big wages, you can pay them enough for soup and that’s it.”

There were many conversations about the latest accident at the plant, which happened two days before, on 29 April. Having completed repairs to one of the blast furnaces, workers tested it, but it spilled 40 tonnes of molten iron in the process. Thankfully, no one was injured, and shop workers dealt with the consequences.

"1,000 Euros instead of 1,000 words". 1 May 2018 in Kryvyi Rih. CC Vector Media. Some rights reserved.

Meanwhile, two dozen members of left-wing organisations Social Movement and Direct Action, as well as anarchist organisations joined the May Day events. In their speeches, these left-wing activists drew attention to AMKR’s involvement in offshore schemes and international solidarity for organised labour, which helps achieve results in concrete conflicts.

The local branch of the Socialist Party of Ukraine, which is friendly with PMGU, marched separately under their own banners, although May Day was supposed to be held without any party symbols. This column spoke out in favour of Serhiy Kaplin. In my opinion, SPU members are wrong to put their hopes for the renewal of their party in Kaplin. He is a businessman who represents the interests of workers in parliament (via FPU) and sabotages the fight against the proposed new Labour Code, which is anti-worker. Kaplin is also linked to oligarch Dmytro Firtash (who faces criminal prosecutions in the US and Ukraine), having originally been part of a political party financed by him, and now regularly appearing on Firtash’s TV channel and organising protests in support of his factories.

The far right also took part in the International Day of Workers’ Solidarity — they traditionally appeal to workers movements in their search for new electorate and members. The Ukrainian far-right political party Svoboda (“Freedom”) has its own trade union, Freedom of Work — and several members of its AMKR branch were present, as well as Yuri Noyevyi, a far-right Kyiv city deputy known for organising attacks on the feminist movement and LGBT activists in Kyiv. He should have been concerned by slogans about equality and global solidarity.

Another Svoboda member’s speech underlined the far-right’s vision of proletarian struggle: it should be waged in support of a “Ukrainian worker’s state” led by the “best” — i.e. Svoboda members and their totalitarian integral nationalism. The anti-democratic spirit of the party can be seen in their trade union, which, according to its charter, is led by a “Head of the Union, a single-person elected position of the union”. Taking into account their small membership, then this election turns out into the worst Soviet ritual of voting for one candidate. The Svoboda members did not take part in the 14 March rally and called on people not to attend the 27 March conference, yet now state on television that they are the leaders of the strike. Worker activists — who are involved in the real struggle against the factory’s owners and management — have the impression that Svoboda members are trying to build reputations for themselves via someone else’s struggle, creating an image as a socially-oriented party. They’re also useful for the AMKR administration, playing the role of “controlled radicals”.

A marathon with hurdles

After 1 May, AMKR management and trade unionists managed to square off for another few rounds. While in April, the factory administration tried to prolong the reconciliation commission in any way possible, since the beginning of May it seems to have agreed to join the negotiation table. Their policy, however, hasn’t changed — they’re still applying administrative pressure, legal manipulations, buying people off and frightening others. Management has now raised workers’ wages by 12%, inferring that a bird in the hand is better than an exhausting struggle against a team of professional lawyers and managers with connections to the state apparatus. On 3 May, a meeting to agree who would be represented on the reconciliation commission turned into a 25-hour marathon. Here, management played for time, the police blocked union representatives from leaving the room, and workers held a spontaneous protest and nearly occupied the factory administration building. In the end, the necessary documents were signed and the reconciliation commission confirmed by both sides.

On 10 May, the reconciliation commission finally held its first meeting; secretaries were appointed, and procedures were confirmed. It seemed that it would now be possible to begin examining employee demands. But alas the next day it turned out that the administration has filed a court case the previous week, demanding that the 27 March conference be declared illegitimate. The owner will try and stop the reconciliation commission while the case is heard in court. These kind of manoeuvres can last for a very long time.

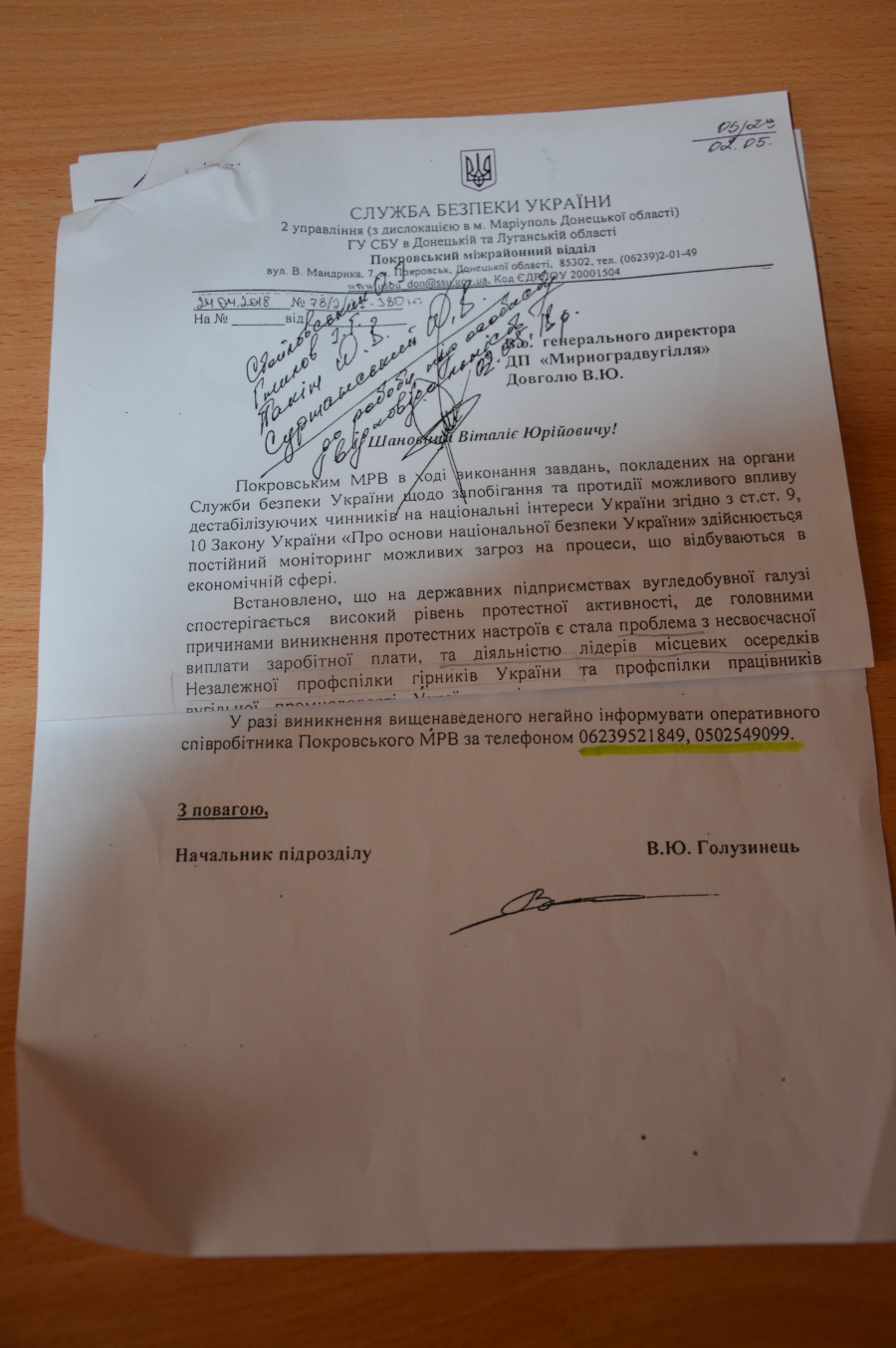

At this point, the state decided to get involved — after all, it is led by big capital and is concerned with its problems. The city’s State Security Service department (SBU) took an interest in the activities of the independent trade unions. And this is a manifestation of a direct policy: in Donetsk region, the SBU recently requested that mining companies report on the activity of independent unions as potential “destabilising elements”. Perhaps they consider dividing the interests of labour from the interests of capital “separatism”.

An April 2018 letter from Ukraine's State Security Service (SBU) demanding that mine managers in the Donetsk region keep the SBU informed of independent trade union activity and "destabilising elements".

The Kryvyi Rih unions’ appeal to state institutions is completely understandable and symptomatic — your average Ukrainian is far more law-abiding than those who write or enforce the laws for them. Unfortunately, Ukraine’s current political elite comes from those social circles which actively practice “optimising” and “minimising”. As Zakhar Popovych states: “AMKR is obviously avoiding tax on a significant amount of profit in Ukraine, and is hiding its real income and profit from its employees. It’s possible that the amount of tax to be paid could be subject to informal agreements with Ukrainian oligarchs. And it’s the job of creative accounting to figure out which proportion of operations should be carried out for real prices, in order to pay the agreed rate of tax, and which proportion should be released from tax via transfer pricing, and then play the fool and show your empty wallets to workers.”

Our locomotive is hurtling forward…

But there’s more to life than highly paid lawyers and corrupt public officials in their sterilised offices. Help for the AMKR workers came — naturally — from other workers. On 14 May, independent trade unions on Ukraine’s railways started a work-to-rule action, demanding higher wages, the return of cancelled privileges and new locomotives. AMKR’s railway shop also joined the “Italian strike” as it’s called, driving their trains into the repair yards and stopping the transfer of ore to the furnaces. The factory’s general director contacted the police with a list of “crimes” committed by AMKR employees, before starting a rumour that the factory would close, and that Ihor Kolomoisky and Rinat Akhmetov (Ukrainian oligarchs who own part of the Kryvyi Rih complex) are involved in the conflict. Independent trade unionists responded: it is factory management who are responsible for the situation, and there is no strike — employees are simply refusing to work in injust and unsafe conditions.

Serhiy Moskalets, Free Union of Railway Workers of Ukraine, announces a work-to-rule action at Kremenchuk rail depot on 14 May 2018. Source: Nabat TV>

Serhiy Moskalets, Free Union of Railway Workers of Ukraine, announces a work-to-rule action at Kremenchuk rail depot on 14 May 2018. Source: Nabat TV>

On 18 May, the AMKR administration made their move, deploying strikebreakers with the help of the state. Locomotives from Ukrainian Railways began working at the factory; militarised security was brought onto the site. When millions of dollars are under threat, workers find themselves looking down the barrel of a gun. Kryvyi Rih residents are trying to remind these people — who are serving the interests of others — about the unity of class interest.

The situation at the factory and around it is now so tense that ArcelorMittal’s owner Lakshmi Mittal was supposed to visit Ukraine on 25 May — but this has not been confirmed. Meanwhile, AMKR General Director Parajmit Kalon has offered employees an increase to the factory’s wage fund in November — to the tune of 1.1 billion hryvnia. This figure sounds astronomical, but in practice this will mean a raise to average wages of €130 per month. And the rhetoric found in Kalon’s official communication is striking in terms of its lies and manipulation, camouflaged in evenhandedness and corporate-speak. The rise in wages, so the communication goes, will place the factory in a difficult position; employees are “ruining the investment attractiveness of Ukraine” (An economic counter-revolution! Where is the SBU?); people should be thinking introducing new technologies, not higher wages. Who has prevented ArcelorMittal over the past 13 years to stop using the last Martin furnaces in Ukraine (Kulytskyi 2016)? Of course, the director did not mention offshore schemes at all. Instead, the top manager pressures employees by referring to figures with an innumerable amount of zeros and hints of a future apocalypse, but you can feel his personal despair when he read out the words “when our blast furnaces will be full again” in a recent video address to workers.

The labour conflict in Kryvyi Rih is not over. There will be yet more twists and turns, which we will follow on Commons. Perhaps a full-blown strike will break out, but a truce is likely to be found soon. The confrontation will remain, and this specific conflict between independent trade unions and the owners of AMKR is part of a more general class struggle between labour and capital. This struggle happens every day in every sector of Ukraine’s economy, politics and culture: when you take on extra work to deal with high prices; when parliament passes another law; when Volodymyr Viatrovych, head of Ukraine’s Institute of National Memory, speaks from a tribune. For the most part, organised labour is in retreat — so at first glance, this doesn’t look like a struggle at all, but the victory march of neoliberalism over the ruins of the Soviet Union.

150 years of workers’ struggle

The fact that there is a real struggle — in which workers have a chance of winning — taking place in Kryvyi Rih is not an anomaly. Some of the largest deposits of iron ore in the world are located in the Kryvbas, and these not only produce an magnetic field and radiation, but also change the society of people who live above them.

Beginning in the 1880s, the development of these deposits and related industry have sped up changes in the social order, and the production of new goods by new methods, in their turn, has brought transformations in political life, spreading new cultural practices and acceptance of modern ideologies. To put it simply: modernisation. And both in Ukraine and outside it, the industrial era has meant dealing with the following questions: who determines the path and tempo of modernisation processes? Who allocates the goods that it brings in? Who launches the new cycle of this never-ending process? This is the question of democratisation. The city’s resource and production power has meant it was here, in Kryvyi Rih, where seminal battles for the modernisation and democratisation of Ukraine have been fought.

In 1905, Kryvyi Rih workers were part of the strike movement that eventually forced the Tsar to offer compromises, legalise political parties and trade unions, and create a parliament, which, however, was quickly subordinated to the ruling classes of the time. In 1917, Kryvyi Rih residents developed a new form of democracy that was supposed to be truly popular and responsible — a council of deputies. Seventeen years later, Kryvorizhstal — the largest industrial site built in the first Five Year Plan — was opened. But the Stalinist faction of the Bolsheviks implemented industrialisation at the cost of turning Soviet democracy into a fiction, the super-exploitation of peasants and workers, a famine with millions of victims, state terror against dissenters, and transforming party functionaries into a new elite.

In 1963, Kryvyi Rih workers revolted against the post-Stalin regime, which had stopped using the most brutal forms of repressions, although continued its total power and control over the working class (Popovych 2017a). The rebellion in the district of Sotsmisto (Socialist city) became the largest public disturbance in the Thaw period, “Ukraine’s Novocherkassk” (Gorbach 2013). At the end of the 1980s, Kryvyi Rih would host a strike movement by Soviet miners — a form of proletarian struggle for self-emancipation from the power of the nomenklatura, which, having failed at the project to modernise the economy, then agreed to a policy as extreme as democratisation. But the democratisation of the 1990s turned out to be ephemeral, and led to deindustrialisation instead of modernisation.

In 2005, the whole world watched as Yulia Tymoshenko’s “Maidan” government nationalised and then reprivatised the country’s largest factory. The year before, President Kuchma’s son-in-law Viktor Pinchuk and Rinat Akhmetov had privatised AMKR for $800m — only for it to be sold by the state for $4.8 billion to Mittal Steel in 2005. The “progressive” faction of the post-nomenklatura ruling class thus tried to implement democratic reforms from above, attracting foreign capital to modernise the economy. But the “radicalism” of the new authorities was exhausted in the process of reprivatising Kryvorizhstal, and the events that followed demonstrated both that the ruling class, competing against one another over their “progressive” and “popular” credentials, pushed Ukraine towards war and destruction, and that international corporations operate here not according to the rules of developed states, but corruption schemes and super-exploitation.

What are we fighting for?

Today, Kryvyi Rih workers are involved in a struggle that could have far-reaching consequences for the whole country. The protesters’ main demand is raising wages, but this issue isn’t limited to buying medical insurance policies, new washing machines and holidays abroad. Higher wages are a necessary condition for developing real forms of democracy in Ukraine. Workers with good wages can spend more time and resources on participating in political life, gain better access to information and (self-)education — and thus the right skills for making decisions. The events in Kryvyi Rih prove that workers can break through the smokescreen of bourgeois manipulation to the real nature of things, and propose well thought-out (in comparison with the factory owners and officials) policies. The left-wing intellectuals’ main task remains explaining the nuances of political economy to workers and putting their struggle in the broader context. It’s nothing new, but this is the classic first step that needs to be taken as part of a long path towards progressive change.

Workers at large heavy industrial plants are a minority in the working class, but in this sector of the economy there are still the conditions that make self-organisation and struggle possible. This is why metal workers and miners, as they get results in their conflict with management, present an example of collective action and inspire workers in other sectors, where the instincts of self-organisation aren’t so well developed. This could produce a domino effect. The realisation that group interests are the base for forming genuine pluralism and directing class struggle into a constructive direction. Thus, real social groups and collectives can come to replace the all-encompassing constructions of “Ukrainian patriot”, “Soviet person” and “homo economicus”. These social groups can define their own course of action in free discussion and through forms of grassroots democracy. This is why Kryvyi Rih workers are doing now. Independent trade unionists are convinced: decentralised structures contain the strength of protest. The AMKR management simply doesn’t know who the unions’ main decision-maker is (this person simply doesn’t exist), and therefore who to pressure first.

By raising the issue of transfer pricing, the workers of Kryvyi Rih are presenting the vices of the ruling order and the defects of the current course of economic development to the court of public opinion. This will, however, present them with new problems. If the trade union movement can bring the plant’s finances out into the open, then they will have to have a say in how those funds are used. After all, democratisation without modernisation always slips into a scramble for limited resources, one that is harmful for society as a whole. The infrastructure in Ukraine’s mining and metal complex needs to be renewed, and the priority needs to be given to producing complex goods. The taxes on profits that a renewed heavy metallurgical industry could bring to the Ukrainain state could be used to develop new hi-tec enterprises and social welfare (healthcare, accomodation and education). State power and big capital have clearly not done this and will not do so (Bojcun 2013), even imitating its fight against offshore schemes (Popovych 2017b).

This returns us to the question of workers’ control over production, the real participation of the working class in discussing and voting on political decisions at the national level (impossible without creating modern workers’ political parties), as well as developing international cooperation of organised labour — the only symmetrical response to the power of transnational corporations. If in the last century, the movement in this direction led to unexpected and sometimes opposite results, this does not mean that we have to refute those ideas. Today, history is made in struggle.

Translated into English by Thomas Rowley.

First published in openDemocracy.