Sarah Cameron is an American historian at the University of Maryland. Her research interests include the history of crimes against humanity, environmental issues, and the societies and cultures of Central Asia.

In 2018, she published a book about the famine in Kazakhstan (Asharshylyk), The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan. The Ukrainian translation of the book is set to be released next year by Academic Press. Based on this work, we discussed the causes, course, and consequences of Asharshylyk.

Iaroslav Kovalchuk: Why did you decide to study famine in Kazakhstan? What drew you to this topic?

Sarah Cameron: I was first interested in Central Asia because I thought it was underresearched compared to other areas of the Soviet Union. At that time, I was a graduate student studying Soviet history at Yale University. When I looked at Central Asia, I realized that many historians focused on Uzbekistan, and they used that example to generalize about Central Asia as a whole. But of course, when you look closely at these countries and societies, they are actually very different. I thought Kazakhstan was a big and important country. It is tough to find many books by Western authors about it. So, I wanted to focus on Kazakhstan, and I decided to start learning Kazakh.

That was really the summer when I went to Kazakhstan and became familiar with the country’s history. I started looking at textbooks for high schoolers and just kids' books written for Kazakhstani students. And I saw mention of this famine. And I thought this was so striking. Taking all these courses in Soviet history, and I had not heard of it. I noticed that many leading figures in my field, when I mentioned it, had only the faintest idea that there had been a famine in Kazakhstan. And that was at that point I realized, ‘Oh, gosh! That was really important topic, of course, not only for Kazakhstan and its past, but also for our understanding of Stalinism and the Soviet Union more generally.’ So, after that summer of me beginning to learn Kazakh, I decided that I would work on it.

What was the natural environment of the Kazakh Steppe before the Russian Imperial colonization? What were the risks of famine for the nomads then?

There were several defining features of this environment. One defining feature was water scarcity. This was a landscape where water could be hard to find. Another defining feature was the lack of good pasture land. Good quality soils might change rapidly from year to year in the places where you could have settled agriculture.

So, Kazakh nomads practiced pastoral nomadism or the herding of animals. This was an adaptation to many of these steppe environmental features, namely, the scarcity of pasture lands and scarcity of water. Rather than being a backward way of life, which many outside observers framed it, it was actually an adaptation to these environmental features. There were nomads who moved seasonally from place to place and took advantage of these scarce environmental resources.

Another feature of the steppe was that rainfall could vary greatly from year to year. So, one year, you could have great rainfall, and the next year, you could get much less. So, it was quite highly variable. The steppe would have a period of drought. As I point out in my book, some of the first settlers from European Russia who came under Russian Imperial rule had a very difficult time adjusting to the steppe environment. Many of them starved. The authorities even closed the steppe to colonization at a certain point.

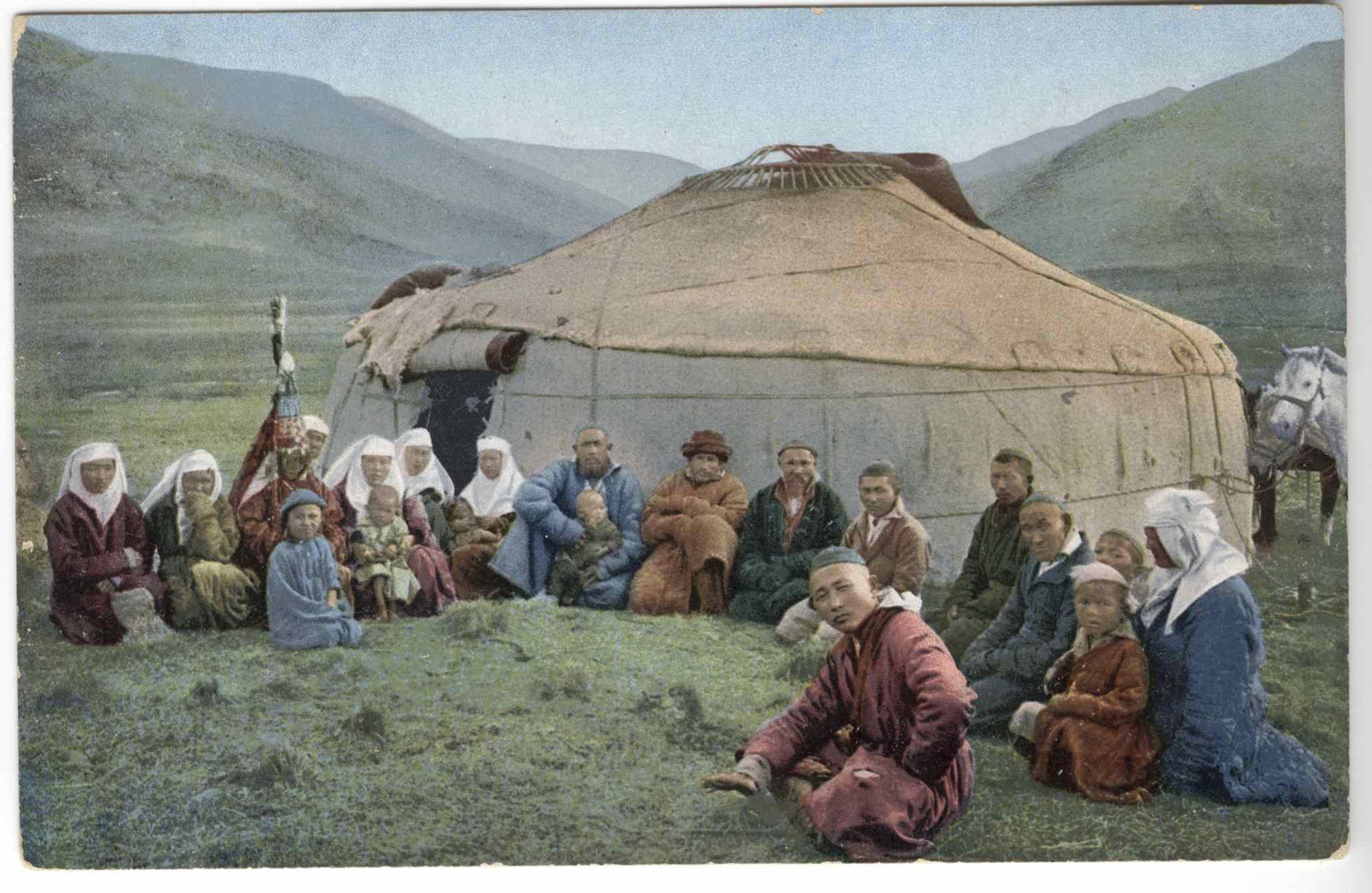

Kazakh people in a yurt. Photograph by Sergei Borisov, early 20th century

How did the Russian settler policy affect the life of nomads and the steppe ecosystem in general?

Many studies of collectivization focus on the years around Stalin’s decision-making. Of course, it is really important to understand that. But that is not how famines are studied in general if we look at them globally. They are always understood to be a product of several factors. One is short-term decisions, but also broader patterns of vulnerability.

One of the things I wanted to do in my book was take a step back and examine the longer history of Russian imperial settlement in this region. I also try to show that many things done under Russian Imperial rule made Kazakhs much more susceptible to famine. This included things like changing the basis of their food diet. It included the changes in migration routes. Many of these things made Kazakhs much more susceptible to famine. It did not cause the famine, but I argue in the book it was a contributing factor.

How did the Kazakh population react to the 1917 revolution?

Many Kazakhs rejected it. First, I would say that the revolutionary period in Central Asia as a whole was not fully studied. We require much more works on it. It is a complicated period for scholars to study because you are dealing with many different languages at that point. Many of the region's vernacular languages were written in an old Arabic script. It also creates complications in reconstructing what happened. But at that point, many Kazakhs resisted Bolshevik rule. The most famous example of this is Alash Orda, which was a native Kazakh government that briefly ruled over the area that traditionally belonged to the lands of the Middle Horde Kazakhs, the area around Semipalatinsk, today’s Semey. They briefly had a Kazakh government that sided against the Bolsheviks.

After the revolution, to what degree were the Soviet modernization project and the nomadic way of life compatible, especially before the First Five-Year Plan? As you say in the book, was it possible to get to socialism on the back of a camel?

There was a lot of debate during this period. The 1920s was a period of much greater fluidity. For Moscow, nomadism was a puzzle because it did not fit into the matrix they brought with them from European Russia. Marx wrote about workers and extending revolution to workers. Then, you make another leap to extend this idea to a predominantly peasant country, which was the falling Russian Empire. Then, you need to take a further leap when you think about how it may fit into a nomadic society.

So, the Bolsheviks were puzzled by the idea of a nomadic society. Did nomads actually have classes in a way the settled societies did? There was one strain that saw the nomadic society as egalitarian. Initially, some even believed that the communist party could work with nomads rather than be against them. They might have nomadic schools and nomadic hospitals. Initially, in the 1920s, there is some evidence of the communist party working with rather than against this nomadic way of life, trying to support it.

Then, for various reasons, they turned against it. One reason was that they moved to this economic model, which wanted very predictable yields. Nomadic life fit poorly into some of this. Another reason was that some of the people who initially supported keeping nomadism under communism had a so-called suspicious background—they had a non-Bolshevik background. The purge of them overlapped with a purge of that position.

You also discuss nationality policies in light of the socio-economic changes the First Five-Year Plan brought to Kazakhstan. Terry Martin claims that nationality policies belonged to soft-line policies whose main task was to popularize hard-line policies to which socio-economic transformations belonged. But you claim that the nationality policy and collectivization were interconnected more closely. Could you elaborate on this connection between nationality policy and collectivization in Kazakhstan?

In my book, I don’t see a distinction between soft-line and hard-line policies. Many soft-line policies can be very destructive. I don’t think that nationality policies should be separated in that way because they were often inseparable from these economic policies. It was intertwined in every single way. Many hard-line policies, like collectivization, were totally interconnected with nationality policy. The goal was not only to ensure a reliable source of grain and meat for the regime but also to develop the Kazakh nation through sedentarization. I also don’t see operating on the ground the idea that some aspects of nationality policies could be held out as a carrot for people to go along. A lot of Kazakhs resisted some of these soft-line policies.

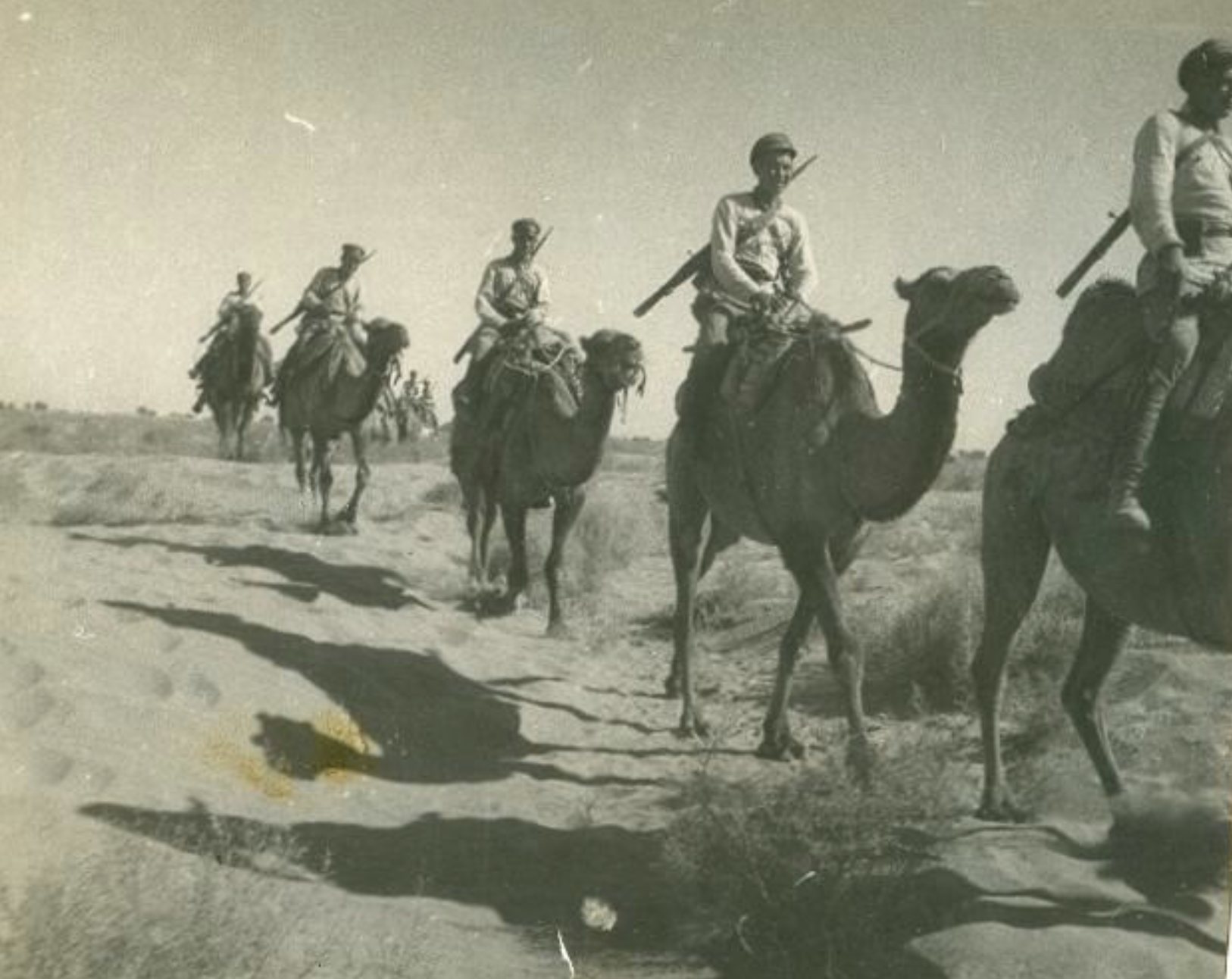

Red Army soldiers on camels, 1920s. Photo: Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

So, in the late 1920s, the head of the Kazakh Communist Party, Filip Goloshchekin, proclaimed the policy of Little October. Why was it called Little October? And what was this policy all about?

I also found the name Little October to be suggestive. The Communist Party had come to believe that Kazakhs themselves had not experienced the October Revolution and that they had to catch up and undergo a social revolution that the rest of the former Russian Empire had already gone through at that point. So, the social revolution, in part, was eliminating members of the elite through the bai confiscation campaign. The bai is, in some senses, the Kazakh analog of the kulak. And so, they targeted a couple hundred of what they saw as prominent and wealthy Kazakh figures.

So, was that the first step to the collectivization of the Kazakh nomads?

That campaign is really quite important to the later path of collectivization because what it did was it drove a wedge in Kazakh society. It turned Kazakhs against each other. It was the first step to destroy Kazakh society from within. Certain scholars might frame it as something imposed from the outside. But that doesn't get at the true brutality of what the Bolsheviks were doing. They were trying to turn people against each other on the inside and have Kazakhs carry out acts of violence against other Kazakhs. They specifically empowered Kazakhs to do this, and they left the campaign terms quite flexible. So, that is what the bai confiscation campaign, or in other words, Little October, did in 1928. The collectivization didn't begin until 1930, but it set the stage and helped to mobilize people and prepare them for the later collectivization campaign.

What was for Kazakhs in this campaign? Why did they join it?

I think we see some of the same motivations that we see in other parts of the Soviet Union. Sometimes, the regime tended to target people who were outsiders in their own societies, maybe people who were orphans or who were on the edge of society. There's definitely evidence that some people joined out of true belief. There was some overlap between their beliefs and the communist ideology. I would also add settling old scores.

The Bolsheviks usually described such campaigns as class warfare. But we're talking about nomads, and they don't have the same categories, like kulak. So, how did the Bolsheviks apply these categories relevant to the peasant society in Kazakhstan?

There is some evidence that it was very difficult. This is a society that is largely an oral culture, rather than a literary culture, and most of the sources that we have about Kazakh nomadic society were written by outsiders. They had their own biases and problems and were written through the lens of evolutionary theory. However, I would argue there is some evidence that there were some elements of class warfare in some of these battles. Some actually did turn against this figure of the bai. There were wealthy Kazakhs who had grown wealth here on the eve of the revolution and who held large numbers of cattle. So, that might be one cleavage.

Another cleavage is that of clan. Kazakhs belonged to super-tribal confederations. There are three hordes in Kazakh society, and for some, this was about battles to strengthen one’s clan. And then there are clans within these super-tribal confederations. So, this was definitely one kind of cleavage that emerged. I would also say religion is probably another one, Islam. So, there were many different acts of rebellion in this period. Some people were trying to start up an Islamic state. So, that's probably another kind of cleavage that I would point to as well.

One of the paradoxes of this early collectivization campaign that you discuss is the sharp decrease in livestock. So, how would you explain it? The policy goals were different, and Moscow wanted to have Kazakhstan as one of the main meat sources in the Soviet Union. But the result was quite the opposite.

Yeah, I think this is an example of what we see in other Soviet planning across the Soviet Union. The orders were given, and then plans were developed only afterward for many specifics. But that became hugely problematic in the case of livestock. For instance, they didn't think that livestock ranged over large territories. They didn't think about how they were going to provide fodder for this livestock. They also did not think about what might happen when we put all this livestock together. Many of them contracted various diseases and died.

Another thing that happened was that many Kazakhs did not want their livestock to be confiscated. So, they resisted by slaughtering their livestock. This leads to a precipitous drop. Another reason is that some Kazakhs hearded their livestock across borders. This is particularly true in the case of Xinjiang, where people took their livestock across the border to evade confiscation campaigns. This is one of the great ironies of collectivization and surely an unintended outcome, which resulted in this enormous and precipitous livestock drop.

The other reason is that many Kazakhs in the initial phase of collectivization had to meet grain procurement requirements. When Moscow or even Almaty looked at the map of Kazakhstan, they imposed various procurement requirements on various regions of Kazakhstan. Sometimes, they very poorly understood the peculiarities of these regions. You would have people living in a livestock region who would have to pay grain procurements. And so, to meet some of these procurements, what do you do? If you didn't grow grain, people had to sell off their livestock to get grain to meet these procurements.

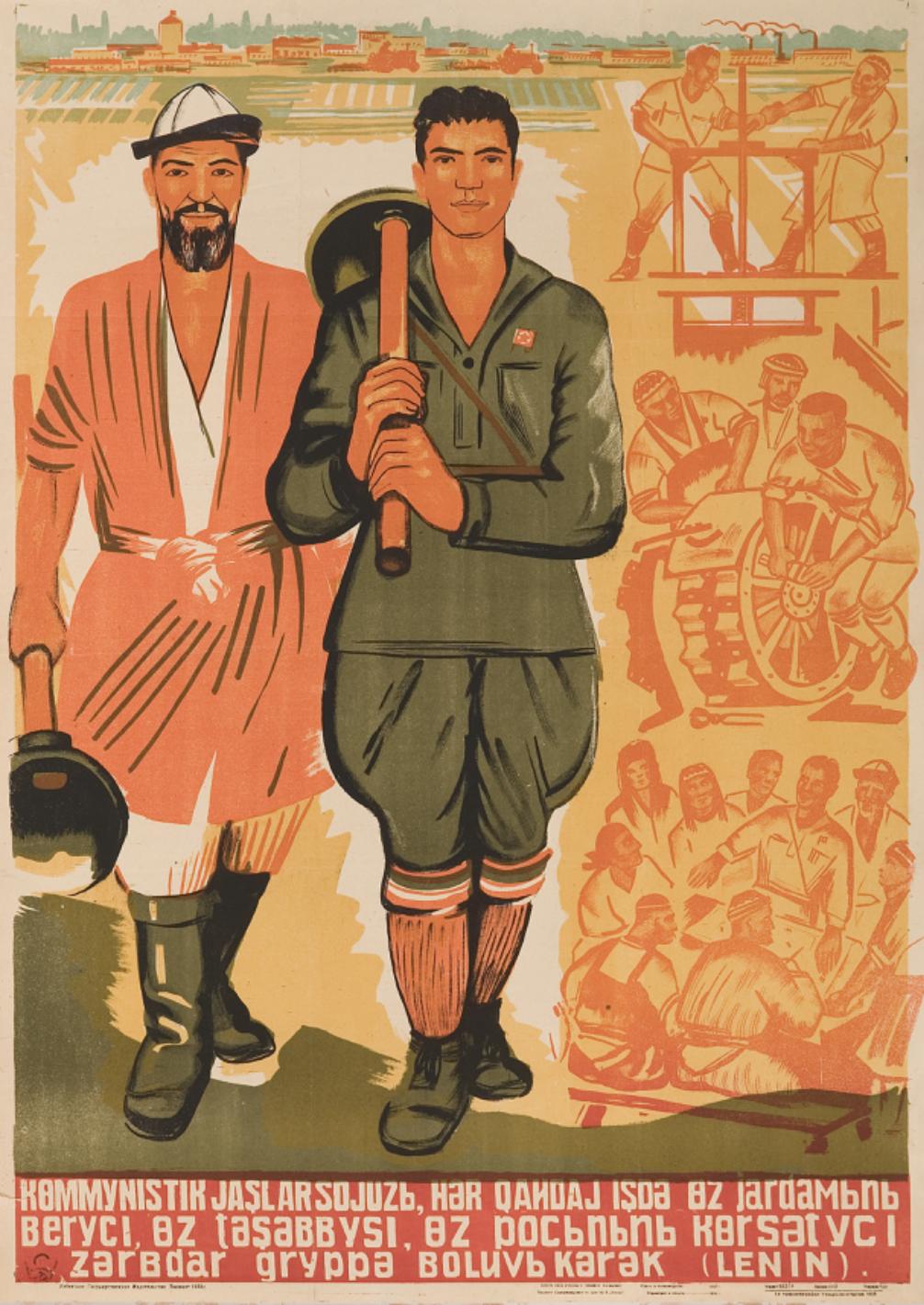

Soviet propaganda poster from 1933 paints a very rosy picture of collectivization. Photo: Marjani Foundation

So, when does the famine start? If we compare the famine in Kazakhstan with Holodomor, the period seems longer in your book. It starts earlier than in Ukraine.

In Kazakhstan, it starts in the winter of 1930. I would argue in 1931, we're well into the famine. 1932 is really the worst year in terms of the Kazakh famine. And then we could probably say it comes to an end by the end of 1933. I think the length of the Kazakh famine is striking. And also, as you say, that it starts earlier than the Ukrainian one.

But why was it so long? If we compare it with Ukrainian Holodomor, we know that it lasted 1932-33, and then relief was sent. But in the case of Kazakhstan, it's several years. Why didn't the party react to it like in Ukraine?

Well, we know that Stalin and others heard that there was famine in Kazakhstan at various points. But they did very little. There were a lot of stereotypes about nomadic life going around, such as nomads having huge numbers of animals and hoarding food. It is incorrect to say that the Bolshevik leadership was not informed about what was happening. They were informed many times, and the word famine was used.

I argue that it was a certain kind of dehumanization of Kazakhs. You might even argue racism. We see evidence of this in how starving Kazakhs were treated. They were treated as less than human. In many ways, they were treated as sort vagrants and beggars. At that point, the party had other priorities. We only really see them taking action when the extent of the livestock drop becomes visible.

The spread of disease is a huge story in the Kazakh case, which is not true to the same extent in the Ukrainian case, as far as I understand. This is huge because many Kazakhs start dying, and as is typical of famine, they start dying of epidemic diseases. That becomes a big concern for the center because of the fear of the spread of disease.

And also the refugee crisis. It is distinct from the Ukrainian case. We have many more starving Kazakhs, something like a million of them, fleeing their own republic, fleeing to places like Russia and surrounding Central Asian republics. And that becomes, in turn, a big problem for these places, who say, ‘Hey, Moscow, help us because we really cannot manage this!’

Another problem they run into is that they're running out of workers. They can't stuff the collective farms; they can't stuff the animal farms because everyone is fleeing. And so it's only at that point that we see Bolsheviks trying to take action when it becomes this immense political problem.

To whom do you attribute the main responsibility for the famine? Is it the republican leadership or Moscow? Who bears what responsibility?

Well, the Moscow, of course, Stalin. In my book, I try to soften a little bit the portrait of Goloshchekin, who has sometimes been vilified as the executioner of the Kazakh people. He was a very brutal leader, but I think there's also evidence that he tried to mitigate or soften Moscow's policies when he could. We have to look first at Moscow.

The horrible part of these policies was that they essentially also tried to destroy Kazakh society from within and turned Kazakhs against each other. Popular participation was quite key to the evolution of this famine. The Bolsheviks were partially successful in mobilizing and activating people. But, of course, Moscow has to be on the top of the blame.

Kazakhs during the famine, 1932-1934. Photo: Central State Archive of Video and Photographic Documents of the Republic of Kazakhstan

You already mentioned that a lot of Kazakhs fled because of the famine. What was the overall response of Kazakhs to the famine? How do you describe it? Fleeing, resistance, or just accepting your fate? What was the response of most of the Kazakhs in the region?

The numbers in the Kazakh famine are a big problem that has been explored much less. We don't have the same statistics as with the Ukrainian famine. Scholars of Holodomor have calculated the death toll with a great deal of sophistication. This simply has not been done in the Kazakh case. And it's one of my major calls when I speak about this topic. I say we have to work on the demographic issue in the Kazakh case much more thoroughly. It just simply has not been done. We know that the death toll was immense, but we really don't have good numbers, particularly how they break down by district.

But in answer to your question, roughly, we can say that in the famine, one in every three Kazakhs died. So that is the number. It is huge, just absolutely staggering. Of those who survived, I think roughly about half of them fled. So we see this immense portrait of societal intermixing at this point – people fleeing to different regions. Some fled internally within Kazakhstan. Some fled beyond its borders. Of course, some of these people were absolutely starving. They were destitute people.

There were also networks of rebellion mixed in with that. But I would say that the vast majority of these people were without any other option. The food had all disappeared, and they were completely destitute and looking for some form of relief. The severity of the Kazakh famine helps explain why we see such a tremendous population movement, which is really distinct from some of the other famines at the same time period in the Soviet Union.

Another factor that explains the huge migration is that Kazakhs were nomads. And as nomads, the flight was often something that they used, a strategy that they used in times of crisis to escape unfavourable political conditions. And even in this famine, we see some Kazakhs following historic migration routes.

But looking at what numbers we have, do we see a significant difference between Kazakh nomads and settlers?

Huge. Again, I would say that we do not have a good and really sophisticated estimate of the Kazakh death toll. In my book, I use the figure of at least 1.5 million. Some Kazakhstani scholars go all the way up to two and a half million, three and a half. I would tell you bluntly we don't know because I have just not seen that work done.

But even with the limited studies that we do have, it's very clear that there's a sharp difference between the fate of Kazakhs and settlers of other ethnicities. I estimated in my book that if we put based on some studies that I had looked at, you know, say 1.5 million deaths of Kazakhstani citizens and within that, 1.3 million of them were Kazakhs. So, if you look at the percentage of ethnic balance in the republic at that time, it was about 60-40: 60% – Kazakhs, 40% – other ethnicities. But about 90% of the death toll was ethnic Kazakhs. So it's disproportionately Kazakhs who suffered from this.

And I think there have been some Ukrainian demographers who have looked a little bit at the question of the Kazakh death toll as part of their broader all-union studies. So Oleh Volovyna is one of them. His study is, unfortunately, a little bit limited because he doesn't cover the full period of the Kazakh famine. It's focused just on 1932, whereas in the Kazakhstani case, there were a significant number of deaths in 1931. Still, Volovyna also concludes that it was strikingly ethnic Kazakhs who suffered.

Kazakhs during the famine, 1932-1934. Photo: Central State Archive of Video and Photographic Documents of the Republic of Kazakhstan

Compared to other nomadic regions of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan still stands out as the worst famine. Why did Kazakhstan suffer the most, even though the initial situation is similar in those terms?

I think this problem needs more investigation. One of the challenges is that we don't actually have a lot of good studies of collectivization. In many of these nomadic regions, for instance, Buriatiia, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, we really don't have a lot of detailed studies of famine. A couple of reasons might help explain the difference.

One would be that Kazakhstan was placed in the first phase of full collectivization. The other regions, like Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan, were ruled as part of the Central Asian Bureau. So a different administrative structure looked over them as opposed to the Kazakh step or Kazakhstan, which was not part of the Central Asian Bureau.

Another reason in the Kazakh case might be the fact that during the famine, Bolsheviks began sending peasant settlers in waves, a couple hundred thousand of them. They were building Karlag (Karaganda Corrective Labor Camp) and GULAG on Kazakhstan's land. So some of these may help explain it.

However, the primary reason was that the Bolsheviks had little understanding of what the land could support. It looks like a big place, a place where you could project thriving greenfields and massive livestock farms. We see this kind of imaginary of Kazakhstan as a really fertile place, also surfacing in later years too. The Virgin Lands Program would be a good example.

So another factor you might add to it is the landscape of Kazakhstan itself. So Kyrgyzstan is, for instance, a much more mountainous place. It's not possible to envisage as a breadbasket. And Turkmenistan is mostly a desert. So it's also a very different landscape.

Kazakhs during the famine, 1932-1934. Photo: Central State Archive of Video and Photographic Documents of the Republic of Kazakhstan

How did the famine end? What did the process look like? Better environmental conditions or the center start helping more? What was the process of overcoming the famine?

One factor might be that they did make more concerted efforts against disease. There were various programs to inoculate people against some of the diseases that were spreading at that point. They reduced some of the grain procurements that people were supposed to give during the famine and meat procurements. They also started to ease some of the policies that they had used before. So just like in the Ukrainian famine, we see them doing very severe policies like blacklisting villages, banning people from entering cities, closing borders, and so on. We see them easing some of those policies. A food aid was also delivered to the republic, but it was very late in 1932. It took a long time to reach people.

Another reason might be good luck. So 1933 was a good harvest. They had good weather. Weather does play a role in the Kazakh famine, not in the simplistic way that we might think about it. The old school way might be, the weather caused this famine, or it did not. Moscow and others were warned many times that the steppe was a highly unstable region for agriculture. You might get good rainfall one year and bad rainfall the next. But they still decided to pursue settled agriculture, even though they were warned. And when a drought happened in the years of collectivization, they still told Kazakhs, you've got to make up the shortfall. They made no allowances for the weather whatsoever. So, in this way, I don't see the weather as an independent factor and should not let Stalin off the hook for it. But 1933 is a better year in terms of weather.

Goloshchekin was really blamed for the grain shortfall. He lost his position in Kazakhstan towards the end of the famine. Moscow sent in an Armenian, Levon Mirzoyan. And arguably, Mirzoyan was a more pragmatic administrator, a slightly better administrator. So perhaps he was able to soften and mitigate some of the party's policies better.

How would you describe the outcomes of the famine for the Kazakh society?

It was immense. One of the key things was the loss of nomadism as an economic system. In the aftermath of the famine, Kazakhs became a largely settled society, not one that migrated seasonally. It's not fair to say that the famine destroyed pastoral nomadism because we still see some. The famine destroyed it as an economic system, but we still see that various elements of Kazakhs' pastoral, nomadic way of life continue to influence Kazakhs. For instance, the current Kazakhstani government has tried to use nomadic life as a usable past and draw upon it in their nation-building efforts.

Clans were an integral part of Kazakh society. A clan was both a social and an economic tie. We still see some of those playing a role in Kazakh life, so that was one major upshot of the famine.

Another one was this kind of intermixing due to this enormous population movement. People moved to different parts of the republic. There is also a large number of Kazakh diaspora in places like Xinjiang, Russia, etc. This is also one of the reasons why it's so difficult to calculate. To do that work, you need to figure out who died. Where they fled? Did they die in China? Did they stay there? Did they come back? And this is very complex to figure out. So I point to that. Some of those issues are the key features of the famine. Kazakhstan itself also became more urbanized in the aftermath of the famine.

Kazakhs became a minority in their own republic. In many ways, the famine precipitates and enables this radical demographic transformation of the republic. We see Moscow sending in additional settlers who are settling on Kazakh former pasture lands, in their former homes. The growth of the GULAG in the post-war period and the sending in of deported peoples during World War II also contributed to the demographic shift. The famine precipitates and enables this very radical policy of population politics. It has made Kazakhstan into a more multiethnic society than it was before, and Kazakhs became a minority in their own republic.

Kazakh workers building the railway to Siberia, 1930

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the topic of famine came up. So, what was the initial policy? How was the government told to interpret and look at this famine?

There was a lot of interest in the famine. Initially, it was discussed in Kazakh language novels. And then, right after the collapse, there is a big upsurge of interest in it. A presidential commission was established to look at it. It declared the famine to be a genocide. There's also an initial wave of rehabilitation.

That's also when we see some of the major studies on the famine coming out. But then this wave of interest goes to the side after a decade of inquiry. Then, famine became a much more politically sensitive topic. It's seen as something that could upend Kazakhstan's relations with Russia.

Was it affected by memory politics in Ukraine, and how did the Ukrainian government's memory policy affect Russian-Ukrainian relations?

First, we really need a good study of the memory of the Kazakh famine. I've always encouraged someone to do that. While writing my book, I realized that I was bumping up against this other huge question, which is the memory of the Kazakh famine. But that's a whole other topic. Think about how many books we have on the memory of the Ukrainian famine. And we have so few on the Kazakh famine. It is such an underinvestigated topic.

Yes, I definitely think that the memory of the Ukrainian famine or the politics of Holodomor influenced the Kazakh case. For instance, I would see some Kazakh scholars referencing the Kazakh famine and calling it Kazakhstani Holodomor. So they would consciously reference that. Also, various Kazakhstani politicians referenced the idea that the Kazakh famine should not be politicized. They don't mention Holodomor directly but evoke the memory in the particular way that the Ukrainian famine has been remembered. They say we should avoid the politicization of our history.

There was another way in which Holodomor surfaced in the Kazakhstani case. There is a strain that I've seen in the literature on Ukrainian famine that connects civil war famine and Ukrainian famine as one common narrative of Ukrainian suffering. More recently, I've seen a lot of interest in scholars in Kazakhstan doing the same thing. They put the famines endured during the civil war and the collectivization in one common lens of suffering. And I believe this was influenced by Ukrainian ideas of the Ukrainian famine.

Unfortunately, there are not many scholars of the Kazakh famine in Kazakhstan today. If you're a young scholar in Kazakhstan and you want to make your career, this is not an ideal topic to work on. I have been told by many young scholars that if you chose that topic, maybe you could do it, but you'd be coming up against constant problems. We have an expertise problem. An older generation of Kazakhstani scholars wrote in the 1990s and produced many excellent studies. But some of that older generation has now passed away. Malik-Aidar Asylbekov, who was one of the leading scholars of the Kazakh famine, passed away. And then this is a topic that the younger generation has not been encouraged to work on.

But I would love to see more dialogue between Kazakhstani and Ukrainian scholars of the famine. I have not seen too much effort to get Kazakhstani and Ukrainian scholars to talk to each other about this topic, and I think that would be really interesting and important.

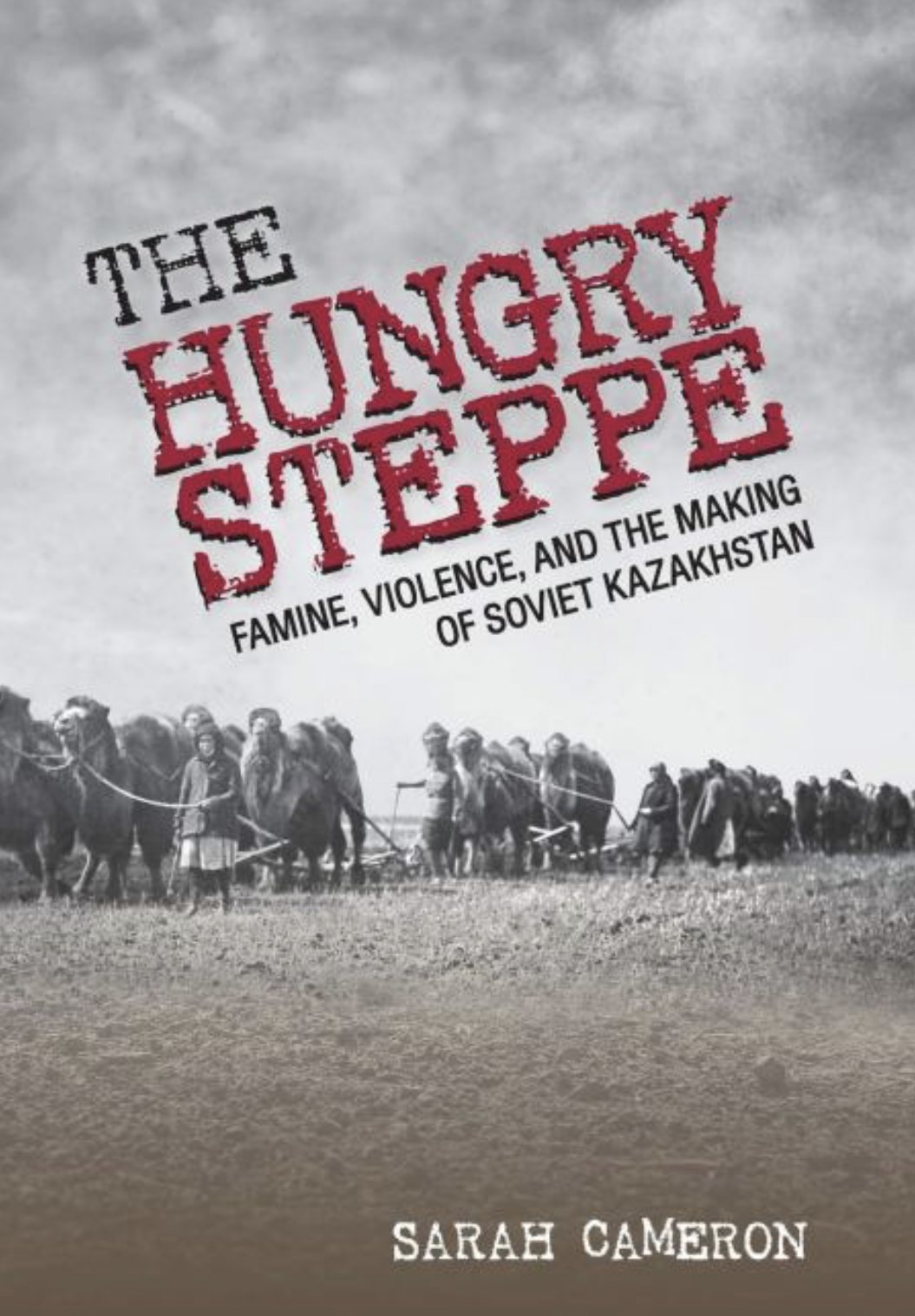

Cover of Sarah Cameron's book The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan

How do you see the difference between Western historiography of famine and Kazakhstani?

In the West, there's been a lot of discussion about nationality policy. And I don't think that is a big issue in Kazakhstan. That is not how they frame questions.

I'm interested in environmental history, which is not an area of inquiry for many scholars of the famine in Kazakhstan. I was also just fortunate as a scholar from the West. I had the enormous privilege of time to sit in the archives and read day after day after day. And many scholars in Kazakhstan don't have that same luxury. Also, because this topic is deemed extraordinarily sensitive, they would be unlikely to get a grant because you need a government grant to do this work. It is unlikely to get a government grant to sit in the archives in Kazakhstan and do long-term projects. I felt very privileged that I had time that many scholars in Kazakhstan simply do not have.

Was there any problem for you or for scholars in Kazakhstan to access the archives? Maybe something was closed?

One difference with Ukraine is that the secret police archives in Kazakhstan are not open. This is a big gap, so if we compare the amount of information we have about the Ukrainian famine and the Kazakhstan case, it's not equal. We don't have those secret police archives, and some other collections are still closed. There has certainly been a lot of movement in terms of declassifying documents in Kazakhstan. I was lucky to use some of these collections in my book, but many collections are still closed.

Your book was translated into both Russian and Kazakh. What kind of response did you receive in Kazakhstan and maybe Russia? Maybe, some valuable criticism?

In Kazakhstan, in particular, I was absolutely overwhelmed by the response. I think the book has been read more in translation than in English. And for me, this was deeply humbling as an author. The most amazing reward that I ever could have asked for is that people in the region read it. And the response in Kazakhstan was largely appreciative. I was very nervous about how some of my claims might be received in Kazakhstan. But for many Kazakhs, it was just the symbolism that an American author had written about this topic. And thus, it was me who brought this to the world stage. And so largely, the attention that I got was very thankful and appreciative.

Prior to the publication of my book, there was also an upsurge of interest on the part of the younger generation about the famine. There's a lot of interest in the younger generation in using history as a tool to decolonize their country's past. And so my book hit Kazakhstan at this moment, where there's an enormous upsurge and energy interest in history, as well as an interest in examining the crimes of the Soviet past. So it really took off. It was all over the place for a while. It's still gone through many different publications and editions. I think the Kazakh translation of the book was particularly important because many people said, look, I can read that book in Russian, but I want to read it in Kazakh. So, the act of reading in Kazakh was itself like a decolonizing act, a declaration against Russian oppression.

The Russian government's reaction was not very positive. People place various imaginings on a book. They don't really read it. And so the imagining about this book was that I was an agent of the US State Department, trying to create a wedge between Russia and Kazakhstan and “create a Ukraine scenario in Kazakhstan.” I've been criticized by all these people in Russian state media and attacked. Their position was not very positive. But again, I wonder did they actually read the book because that was not the position that I was trying to take. But it definitely inspired an enormous amount of debate and interest. So that was great.