Last year, we published an interview with social geographer Tekle Weldemichael about the war in Tigray. Shortly after the publication, we received a critical response from our reader Christian Mamo, who grew up in Ethiopia in a Ukrainian-Ethiopian family and worked as a journalist in Kyiv for several years before the Russian invasion. According to Christian, the interview ignored an important context. We were interested in his letter and offered to organise a dialogue between Christian and Tekle. To our delight, they both agreed to talk. Here is the edited version of the interview.

Daryna. When I first shared the interview with some of my Ukrainian friends, they were shocked because they had never heard of the situation happening to Tigray. So they started comparing it to Rwanda since it'd also been hidden from millions of eyes. My first question to both of you is, how the term genocide is perceived by the Ethiopian community when applying it towards the Tigray region, towards what's happening there?

Tekle. That's a highly complex question. I don't know if Christian agrees with the statement that what happened in Tigray is a genocide, but like I said one starts speaking about Tigray, there is little room for discussion in Ethiopia.

For a long time, the region was effectively blockaded, and very little information was available about what was happening on the ground. The only things that came out were some fragments, testimonies of humanitarian workers who managed to cross the border or stories of people who fled through the mountains. From the fragments of information the Tigray audience received it was clear what was happening on the ground — was genocidal. And when we talk about genocide, it's a heavy concept having both mental elements and a material component to it.

The mental element concerns propaganda and mobilization aimed at causing harm to the population that's being targeted. We’ve heard official statements from the government in Ethiopian media openly talking about "wiping certain ethnic groups off." Often, this happened in the form of "Freudian slips," where officials seemingly spoke about the TPLF (Tigray People's Liberation Front), but their statements implied all Tigrayans.

In terms of the material manifestation of the genocidal practice, you could see what was being done on the propulsion. For example, the entire western and southern Tigray was cleared of local residents. In addition, the systematic use of sexual violence as a weapon during the war was documented. We are talking about hundreds of thousands of women and girls being subjected to rape and sexual violence. And it's not just rape: there are documented cases of soldiers inserting foreign objects into women's genitals.

Mass killings of civilians have taken place across the region. These are not isolated incidents, this is systematic annihilation. Human rights organisations have documented only the tip of the iceberg, as many cases have not been included in official reports. For example, the village where I come from and the towns where I have lived are not in the reports though I know what has been happening there.

When I tell Western experts that I have not been able to contact my parents for almost two years, that my elderly parents were forced to flee their home, that my 88-year-old father was kicked out of his house and died without receiving medical care, people simply cannot believe it.

But the reason why the rest of Ethiopian society is not aware of the full picture is that information about the events in Tigray was hidden from the population. I don't know what Christian thinks about this.

Ethiopian refugees who fled the conflict in Tigray arrive at the Um Rakuba camp in Sudan, December 11, 2020. Photo: YASUYOSHI CHIBA / AFP

Christian. From my observations, there was a lot of even willful ignorance and denial of the expected fact that our army was prosecuting the war in quite a brutal manner. But anybody who follows how our army has behaved in the last five decades would know that this is a kind of standard modus operandi. Still, simply because of the background profile of the party that was leading Tigray in a rebellion, people seemed conveniently reluctant to believe the mounting reports of atrocities coming out. Even though from time to time, bits of evidence would trickle out some horrible videos or whatever, or open-source evidence, a lot of people just chose to dismiss it entirely or downplay the scale of the events. It can also be added that the perception of the Tigrayans as supporters of the TPLF also led many people to ignore the crimes that were taking place.

When the army ended up being pushed out of Tigray, it became impossible to turn a blind eye to the violence. A few weeks prior, government officials said everything was under control. And then they had a whole catastrophic defeat. This made people think about the possibility of being lied to and change their perception of events. Since then, I have seen a very slow and reluctant acknowledgement of the horrors that took place in the North. However, Ethiopians aren't exactly the types that are quick to admit wrongdoing. Therefore, even when people agree that crimes took place, they do so with great shame. However, due to the lack of a common ground for discussion, there remains a huge gap between different groups in society.

What is the role of the Tigray People's Liberation Front in understanding the current conflict in this war, and how does it impact the support people from Tigray are given?

Christian. It's impossible to talk about this conflict, this downright evil catastrophe that happened in the North, without talking about the TPLF — the Tigrayan ethnonationalist political party which took power in 1991 [as part of the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRF) coalition — ed.], ruled Ethiopia till 2018 and led Tigray during its rebellion in late 2020.

Despite the on paper federalism, Ethiopia was never as tightly centralized around one party — or more accurately one sub-party of a coalition of parties — as during the TPLF era. I believe that the nature of this conflict, the brutality with which it was waged, is entirely a story of the failure of a system that had a long time to reform itself.

Just the very existence of the ethnic militias which were responsible for a lot of the worst atrocities of this conflict — like in western Tigray — is a direct result of the politicization of ethnicity imposed by ethnic federalism. Ethnicity became the defining characteristic of public life: it was even printed on the national ID. My father, who is himself half Amhara and half Oromo, was forced to have 'Amhara' written on his ID card, due to his father being Amharic speaking. This is despite him being half Oromo and anyways identifying solely as Ethiopian.

One thing that you should keep in mind is that, however on the scale of history 30 years is not a very long time, Ethiopia, like any poor country, has a very young population. I think our median age is currently 19. So, you have a majority of the population that has been living their lives under a blatantly divisive system, which even encouraged forgetting other ties in favor of ethnicity, and in which ethnicity became the only avenue through which political activity can be conducted. And because of that, there's a direct nexus between the imposition of that and the brutal nature of the current conflict.

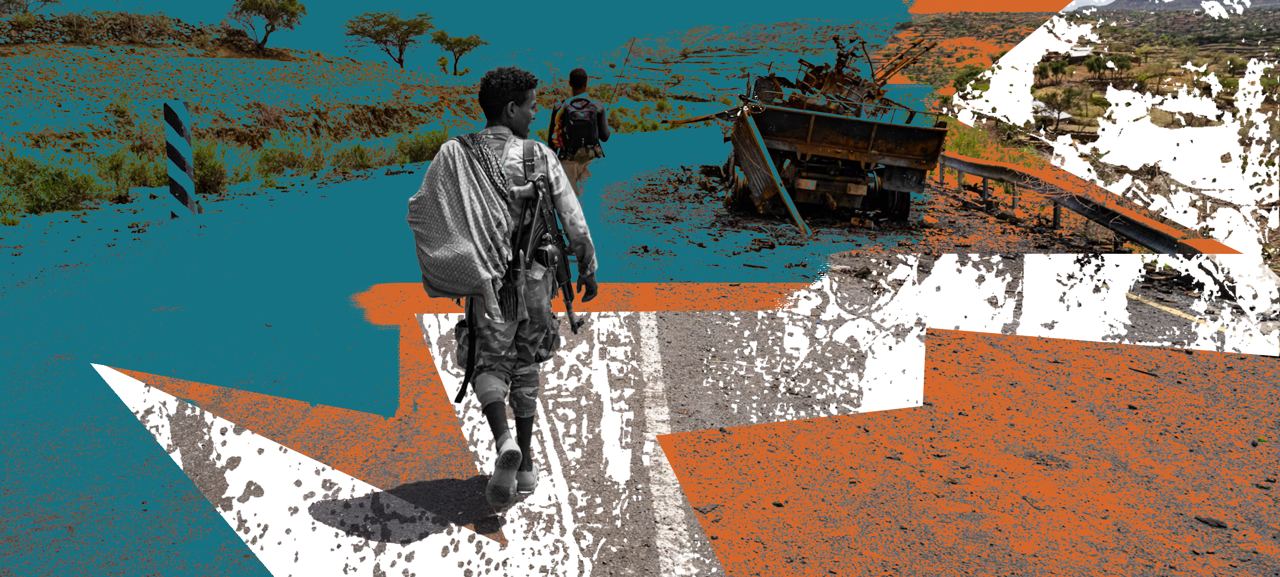

March of Tigray People's Liberation Front fighters in Mekelle, Ethiopia. Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba / AFP

Regarding the perceptions of Tigrayans among the Ethiopian population, there was an unfair notion that Tigrayans benefited from the ruling party for 27 years, as being the Tigray party. That's not true. That rule didn't help the average Tigrayan more than the average person in any other region. But there was that perception that it was their base of support. However, even within Tigray, this perception eroded after 27 years of increasing open discontent with the government.

And I think one thing is indicative: in the early stages of this conflict, during the conventional stage, the military took the capital and other major cities of Tigray quite soon, maybe in the first month of the war. This is despite having lost a significant part of their heavy weaponry during the TPLF's attack on the northern military bases. Such a quick end to the conventional phase of the fighting indicated that even within Tigray, there was a waning popular support for their leadership. However, this support was revived due to the horrendous abuses of the military in the more difficult counterinsurgency phase.

About 80% of Ethiopia's population is rural, so controlling the cities won't mean anything. And then, when you have to go off-road into these hard-to-reach places, the world becomes a lot more complex, and our army responds to the difficulties in its usual way, which is collective punishment. Unfortunately, this is a big part of the modus operandi of the Ethiopian military throughout history.

Tekle. It is worth clarifying a few things. There are a lot of things about federalism. While the federal structure introduced in 1995 is indeed directly linked to the violence of the past four years, it is an oversimplification to attribute all conflicts in the country solely to ethnic federalism. Such a view ignores the history of violence in Ethiopia, which began long before the adoption of the 1995 Constitution.

The current ethnic and federal structure has its roots in the nineteenth century, when Ethiopian empires from the North, from the Tigray and Amhara regions, expanded southwards. This was happening in parallel with the British, French and Italians annexing large areas to their colonies.

Since the 19th century, the practice of slavery has been widespread in the country. The population of the lowland areas was enslaved and sold in various markets. Slavery wasn't based on an economic hierarchy or anything; it was ethnically based.

So, ethnic groups were incorporated into the empire by force and were often subjected to all kinds of harm by the empire and the state. In all the empires of the past we know, the state's violence doesn't remain just in the newly incorporated territories; the old territories also get subjected to that kind of treatment as the state progresses. This violence resulted in the struggle to overthrow the empire, the protest movements of the 1950s and 1960s, and later the 1974 revolution that ended the rule of the last Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie.

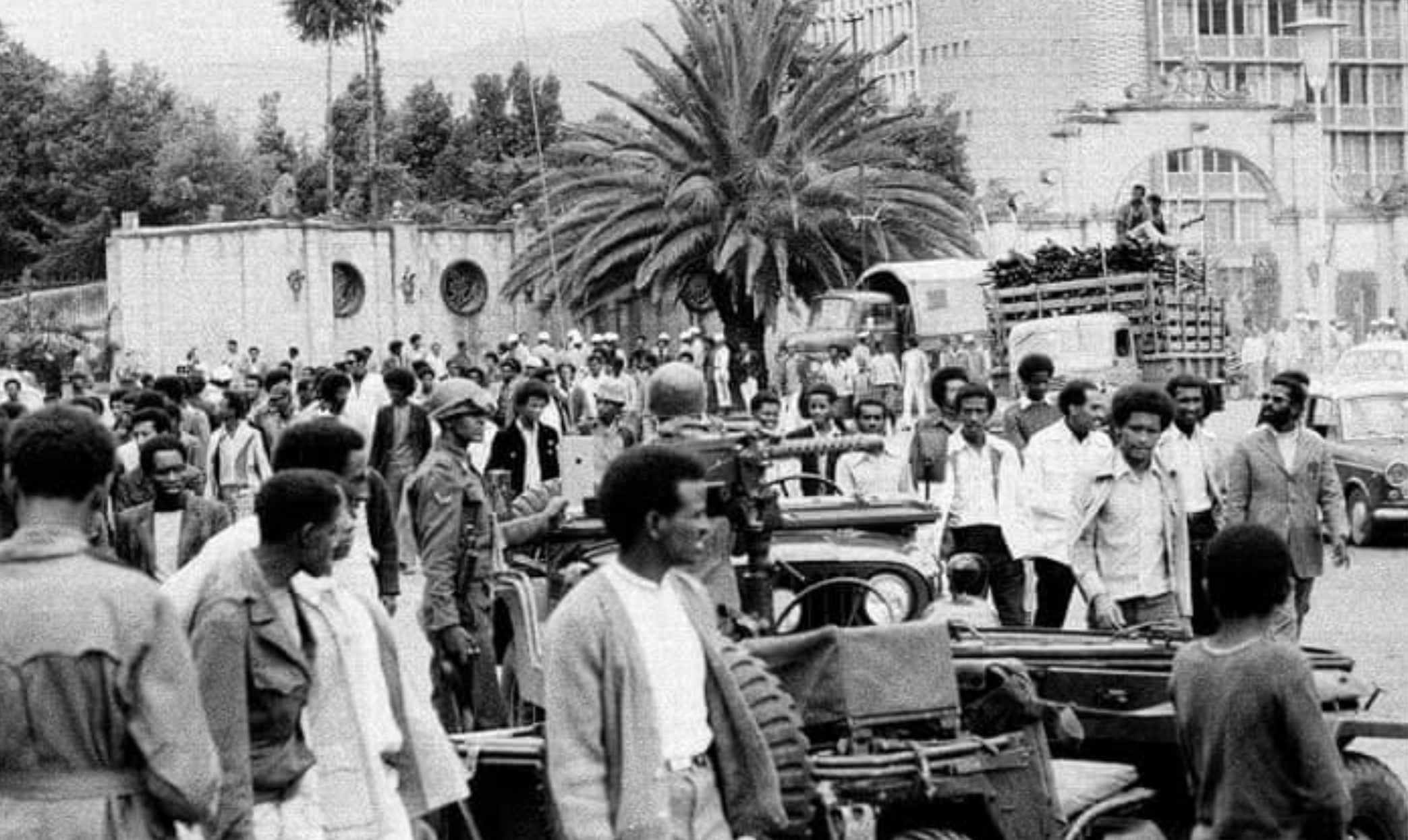

Demonstration in Ethiopia, August 23, 1974. Photo: Wikimedia

The questions that the protesters raised at the time were often linked to the center-periphery debate, in which many regional cultural groups demanded that they govern themselves. For example, they wanted to speak their language and continue to practice their cultural and social customs. The ethnic groups of the conventional ‘centre’ made similar demands. Therefore, to say that the federalism of 1995 was an imposed system is to downplay everything that happened before 1991, and to ignore the wars of the 1980s.

Indeed, the 1995 Constitution contained provisions that may have contributed to the current divisions and violence. But this is largely due not only to its content, but also to the way the Constitution was implemented — or rather not implemented — properly. The problem is that the country's governing party has not been able to properly implement some of the Constitution's stipulations for the last thirty years. This includes addressing the historical grievances of populations subjected to imperial violence and the question of self-governance, which led to the wars in the 1980s.

However, part of the lack of sympathy towards Tigrayans during the current war comes from the perception that the Tigrayans imposed this Constitution. There is a legitimate reason, as the TPLF and the coalition it was part of didn't implement it. And this, in my opinion, is the root of the problem. But it was also basically propaganda by the emerging forces that support the current prime minister Abiy Ahmed Ali. They pushed this conception of the Tigrayans as inventors of the ethnic question. But this is not the case. This is a natural question and has been raised for at least the last six or seven decades before the adoption of the Constitution. It only formalised what already existed. However, the Tigrayans were accused of making ethnicity part of the state system by allowing people to openly declare their identity, which was eventually used by state propaganda to justify the genocide.

Christian. In response to that, first of all, yes, I do acknowledge that Ethiopian history is incredibly violent. In fact, it was a medieval society until the early 20th century. And it had feudalism until the 1970s. Yes, the Ethiopian Empire forcibly incorporated half of its current territory in the late 19th century. But for me, a lot of the ethnic groups that have a much better claim to having been marginalized and oppressed by the Ethiopian Empire come from relatively more peaceful regions today, such as in the South. Also, some of the violence following the imposition of ethnic federalism has happened between historically peripheral groups, such as between the Afar and the Somalis, or the Somalis and the Borana Oromos, the Borana Oromos and others.

And regarding the national question, well, during the imperial era, during the reign of Haile Selassie, there were several rebellions throughout the country. Still, none of these could win decisive victories over the government, let alone seriously threaten the imperial regime. Also, none of these conflicts had anywhere near the brutality we see today. Of course, the national question was an important issue during the revolution. Yeah, but fundamentally, that revolution was a class-based one. It may not have succeeded if it had taken a strong ethno-nationalist character. A significant reason it succeeded is that the first generation of educated urban students was involved. It was a Marxist, class-based rhetoric that helped mobilise student youth, who later joined the ranks of military officers who overthrew the emperor in 1974. But in 1991, when the rebels led by the Popular Front overthrew the Dergue regime[1], the situation was different.

On the one hand, part of the TPLF's policy was a response to the historical national issues. On the other hand, ethnic federalism was more of a divide-and-rule political strategy. Its aim was to divide opposition forces and reduce the threat to the central government, which was under the control of the TPLF.

In my opinion, despite the history of imperial violence, the main factors of the current conflict are the result of the political system that was introduced after 1991. This is particularly evident in its impact on the political socialisation of young people in different parts of the country. For the past 30 years, students have been taught to view their neighbours primarily through the prism of ethnicity. When you learn from an early age that you and your neighbours have ‘competing’ ethnic identities, it shapes a certain worldview.

A man carries mattresses to Tsehay Primary School, which was turned into a temporary shelter for internally displaced people, Tigray, Ethiopia, March 15, 2021. Photo: Baz Ratner / Reuters

Historically, there was also a hierarchy between different peoples in imperial Ethiopia, but the central government did not incite groups to hostility towards each other as openly as it has done in recent decades. This was the main mistake of ethnic federalism. It has fuelled competition and suspicion between ethnic groups rather than promoting national unity. And today, we see the consequences of this in the form of massacres, ethnic cleansing and violence that has engulfed the entire country.

If we want to find a way out of this crisis, we need to critically rethink the system of governance. We cannot simply return to imperial or unitary structures, but we also cannot allow ethnic fragmentation to continue to destroy the country. I think we need to move towards a civic identity based on individual rights, not ethnic divisions.

Tekle. But I agree with you a lot about what you said. We shouldn't ignore or underestimate the role of dialectic in what is being discussed about the Constitution. Never mind that no statement in the Constitution says this is an ethnic federation. It's a federation of people that live in the country, and there is so. But since the inception of the Constitution, since its introduction, there have been intellectual discussions, critics, and supporters who have shaped the debate around the Constitution as if it's an ethnic concession. This is just one example, but much of the discussion since the 1990s has shifted mainly toward ethnic debate. The main question in the 1960s and 1970s wasn't necessarily about the ethnic question. Of course, there was a struggle against oppression, cultural domination, and so on, but one of the key issues was the desire for autonomy, self-government on the periphery, because Ethiopia, as we know it, was a centralised state. And this struggle continued even after the 1990s.

For example, if you go to the country today, I think close to 60% or more — now, because of the war, maybe closer to 70% — of the national capital investment there of happens in Addis. It is a city with only about five to six million people. The remaining 120 million people get 30% of the investment, including infrastructure and capital investment. So, the struggle in the 1960s and 1970s was beyond autonomy or ethnic and cultural autonomy. It was a debate between the center and the periphery: the center being the imperial center in Addis and the periphery being the rest of the country.

I think one of the failures of the TPLF government was to go on without questioning this center-periphery dynamic thereby sliding into the exact structure of the country, which is, I think, fundamentally the reason we have all the mess today. I blame Addis for many of the crises in the country. Addis is the reason we have many of the issues today, and there are many things that we need to discuss about that.

A Tigray People’s Liberation Front billboard in Mekelle, 2024. Photo: Marco Simoncelli / Al Jazeera

Christian. Of course, throughout Africa and Asia, it's standard to have a large metropolis, a capital city with much higher living standards than the rest of the country, and then the second-biggest city. I agree that development in Ethiopia is highly uneven. Addis has the HDI of a lower-middle-income country, while the countryside is vastly different. However, Addis also has a massive secondary economic boost as a diplomatic hub.

I agree that Ethiopia's history and material conditions necessitate a devolution of power and decentralization. My fundamental issue with how it was implemented is not the fact that it was decentralized but rather the grounds on which it was done. Several provisions of the Constitution are problematic.

We should have multiple official languages. I also agree with mother-tongue education despite the practical difficulties of implementing it. I agree that Ethiopia's history necessitates local autonomy and self-rule because there are cultural differences from region to region. But again, these differences are primarily regional.

We had many border areas, such as Western Tigray, which has been a frontier area for centuries and has organically developed mixed cultures. The same goes for places like Raya and Southern Tigray, Wello in the Amhara region, and even Shoa, the capital region. Of course, having schools with different languages, for example, is no problem.

My fundamental issue with what happened in the 90s is the ethnic residence system, and I'll call it reservations because of the word kilil[2] — I think that's the most accurate translation into English. What it did by giving ownership of each reservation to a designated ethnic group or groups is that instead of improving the situation of national minorities, it effectively created regional minorities everywhere who were disenfranchised and disempowered in local politics. In each of these reservations, only ethnicities deemed 'indigenous' would be allowed to run for office, work in civil administration or participate in political advocacy. This system was patently unfit for Ethiopia. A huge proportion of the population is ethnically mixed and multilingual. Regional identities always took precedence over the ethno-linguistic. This has begotten all kinds of ethnic cleansing throughout the country, where this notion of collective land ownership based on ethnicity empowered regional administrations or overzealous locals to expel people who were not designated as indigenous to the reservation.

So, in general, yes, I agree that self-rule, decentralization, and local autonomy are the blueprint for a prosperous and united Ethiopia. However, the problem lies in how it was institutionalized. And yes, I know the Constitution doesn't explicitly say ethnicity — it uses the Stalinist concept of nations, nationalities, and peoples — but that's what it is. And yeah, I think that's the primary problem, not decentralization.

Christian, you also mentioned in your comment regarding the armies and armed forces that ethnic groups started gathering to protect themselves. How did it develop?

Christian. Under Ethiopian federalism, there are two levels of armed forces: a national army and regional armies, branded as special police. Regional administrations were allowed to organize such formations, and they were at the forefront of many human rights abuses during the EPRF era. For example, in the Somali region, a force led by Abdi Ilay was set up to fight Somali secessionists. You can find all kinds of reports about horrendous Ethiopian government abuses in the Somali region — or Somali reservation, as some call it — and these ethnic militias primarily carried out those abuses. Ethnic Somalis and Afars have also had quite a few disputes. Their conflicts go back hundreds of years, as they are neighboring nomadic pastoralist communities with disputes over water, grazing lands, and similar issues. However, creating these special police forces gave them the means to try and resolve these disputes violently.

The ethnic cleansings I mentioned, which have occurred throughout the country over the last 30 years — sometimes accompanied by killings and sometimes just forcible expulsions — were often carried out by regional forces. I think having a parallel military — especially a series of parallel militaries organized along ethnic lines — is a recipe for catastrophe. And, frankly, we've already seen that come to pass.

Ethiopian refugees who fled the Tigray region at a United Nations camp in Sudan, December 2021. Photo: Tyler Hicks / The New York Times

Tekle. So regions were supposed to have parallel power with the federal government. The federal government wasn't supposed to intervene in many regional governance issues, but that didn't necessarily happen. The federal government still had control — almost complete control — over everything. Regions were subservient to the national government. Even though there were significant promises of autonomy, it didn't happen.

Over the last 15–20 years, there has been growing mistrust of the federal government. For example, Abdi Ilay in the Somali region was primarily supported by the federal government, partly to guard some of the area and the borders with Somalia from Al-Shabaab [a jihadist military and political organisation allied to al-Qaeda — ed.]. However, in the rest of the country, there was growing distrust of the federal government, mainly because regions didn't have much power beyond maintaining their militia forces and pursuing some of their local interests. This trend worsened after Abiy Ahmed came to power in 2018.

For example, when I grew up in Tigray, there weren't many local security forces in the neighborhoods. You would have the regional police, who were like civilian police. They carried guns, but they were not heavily armed or militarized. We didn't have many regional special forces during that time. After Abiy came to power, you could feel that the region's autonomy was being threatened. Regions began accumulating military forces to guard against this perceived threat. I can testify to that when it comes to Tigray.

Of course, the situation only got worse. Regions began training soldiers in large numbers. For instance, the Oromo region had 31 or 32 rounds of military training two to three years after Abiy came to power. The same happened in Amhara and Tigray. This buildup led to confrontations between the regional governments and the federal government.

As I mentioned in a previous interview, the federal government mobilized these forces during the war. Some of them aligned themselves with the federal government, joining its efforts during one war, but in the next instance, they would disagree and fight against it. That's exactly what we're seeing today. In the Amhara region, the same forces that were allies of the federal government during the war in Tigray are now fighting the federal government, causing a lot of disaster in that region. This situation reflects the lack of trust in the central government. I don't know where that trust will come from, but Ethiopia's real problem lies in its systemic issues.

But what about that ceasefire treaty in 2022? Did it start any significant processes?

Christian. To be frank, I have zero faith in the current regime's ability to do anything except make the situation worse. I do think that in 2018, Ethiopia was saddled with significant challenges. Still, Abiy is completely the wrong person to solve any of them in terms of general ability, mindset, capacity for empathy, and ego. I don't see things getting any better with this government in power.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. Photo: Luke Dray

Tekle. That's exactly what I would have said as well. I think the 2022 agreement between the TPLF and the federal government is just an agreement to cease fire. So, this is temporary. This is not a comprehensive peace agreement that would address the causes of the conflict, ensure accountability, justice and the restoration of the affected regions. That hasn't happened.

The first thing that needs to happen to move forward is to remove these people from power and establish another process to replace the existing crisis. I don't know of any point in history where people who have committed genocide remained in power while overseeing the peace and reconciliation process. That is simply unnatural, and it doesn't give me any hope for addressing the fundamental questions that led to this crisis in the first place. The first step would be removing these people from the stage.

Are there any possible alternatives to these parties in the current situation?

Tekle. Frantz Fanon has this sort of description of akin circumstances. So, I said, it's a colonial state where we have a mother country and autonomous regions that the federal or central government controls. The scale of the brutality of this state is unmatched. You have parties that claim to gain autonomy for their regions, whatever territories they are fighting for. For example, in Tigray, there's a party with the TPLF, and that party hasn't managed to secure the autonomy it claimed to bring to Tigray.

What we have today is two different kinds of forces emerging in the region. The same parties are splitting into two. There's a section that agrees with Abiy and the central government, saying, "We'll just do whatever the federal government says." Then you have the same people from the same party saying, "We don't agree with Abiy, so we're going to do whatever we want." This pattern plays out everywhere — in the Amhara and Oromo regions. One side supports the federal government and its policies, while the other side says, "Okay, we're going to pick up guns and fight again."

That's just the current situation, mainly because there isn't any widespread, local grassroots discussion on how to move forward. In Tigray people are numb from everything they've been through over the last four years. Speaking about people on the ground — academics, politicians, ordinary citizens — I can't imagine that anyone has the energy or resources to sit down and think about the future right now. There is too much pain, too much economic and social crisis. People are just trying to survive.

Christian. To be honest, I see no alternative. Elections are planned for next year, but, as always, they will not change anything.

But if you look at history, it becomes obvious that Abiy somehow managed to avoid the fate of other African transit leaders, such as Morsi or Hamdock. He has to be doing something right. Not right in a good way, but correctly in terms of retaining his hold on power.

Ethiopia has gone from an imperial regime to military communism to the tight grip of the TPLF for three decades, and they just haven't developed the kinds of institutions you'd expect to lead the country through such challenges. I mean, the whole reason the military took power after the revolution in 1974 was that lack of institutional capacity. Fifty years later, and although new forms of social organisation have emerged — trade unions, gender movements, religious associations — they have not been able to develop into influential political forces.

The main problem is the ethnic politicisation of the Constitution. This destroys inter-ethnic ties that could serve as a basis for broader coalitions and democratic change.

Children play in front of a house damaged during the fighting in December 2021, Tigray. Photo: Eduardo Soteras / Agence France-Presse

Tekle. There is no other way to solve this issue in the future except by changing the current federal structure or redefining the basis of federalism into a different form of co-operation. What we see today is, to a large degree, the result of the politicization of the Constitution itself. When Abiy came to power in 2018, his initial approach was to free the country from centralized control and allow regions more autonomy to progress. However, his support base quickly shifted from pro-autonomous, decentralized governance to the political elite at the center. His policies increasingly aligned with urban political interests rather than decentralized governance.

This shift is at the core of today's struggle. Ethiopia's challenges cannot be addressed by elites in Addis Ababa, Mekelle, and other significant cities discussing matters among themselves. A broader, more inclusive dialogue is necessary.

Rather than dismantling institutions, the focus should be strengthening constitutional guarantees and addressing existing shortcomings. The priority should be ensuring people's rights are upheld, as the Constitution outlines. I do not believe in dismantling institutions to create something entirely new, as history has shown the risks associated with such an approach. Instead, reform and adaptation within the current framework would address Ethiopia's challenges more effectively.

Christian. I would also advocate gradual changes rather than radical dismantling. After 33 years, the current arrangement is a reality for many people, and some positive developments have resulted. It has provided stronger protections for peripheral languages and cultures, allowing them to be preserved and flourish.

The system doesn't need a complete overhaul. Sudden radical changes can destabilize fragile and poorer countries, particularly in Africa. Although this may not sound very left-wing, gradual reform is often the better approach in such contexts. We saw this in Tigray, where a significant number of deaths during the conflict were not just due to direct violence by armed forces but also indirect causes, such as the collapse of the healthcare system. Completely dismantling the system would only risk further instability. Instead, fundamental reforms should focus on better protecting the rights of regional minorities so that people do not feel vulnerable.

Much of the ethnic cleansing over the past 30 years has not been mere communal violence but rather the systematic targeting of defenseless, impoverished communities by newly empowered ethnic militias. Stronger protections for regional minorities and a de-ethnicization of politics are necessary. For instance, in a proper democracy, if a candidate from Addis who does not speak Somali runs for mayor in Jijiga, it is unlikely that anyone there would vote for him. However, at the very least, there should be a possibility for a non-ethnic Somali — someone born and raised in the region, well-liked, and popular — to represent the community. The goal should be to reduce the extent to which a person's life is dictated by the ethnic category they are born into.

The country will face even more significant problems if these issues are not addressed. The current system fuels polarization and deepens divisions between groups.

Orthopedic and physiotherapy center in Mekelle, Tigray, 2024. Photo: Marco Simoncelli / Al Jazeera

What do you think can be done to support the discussion of this topic and help resolve the situation?

Tekle. Over the past four years, my focus has shifted. Before the war, I wrote about Kenya, Tanzania, and other global topics. However, since the war began, I have concentrated more on Ethiopia and primarily on Tigray, and the country's broader situation. As an academic, I see my role as crucial in this context. For example, many of my childhood friends and neighbors struggle to articulate what they have experienced during the war. However, as an academic, I can create or borrow the necessary language to help explain their experiences. My role is to make the situation in Ethiopia legible to the rest of the world. I am not sure whether I am fully capable of this, but it is an effort I am committed to pursuing.

What we are doing today e.g. bringing scholars and concerned individuals together is essential. Creating platforms for discussion such as this is important. It allows us to engage with different perspectives, though our views on Ethiopia do not seem vastly different. Our task is to foster dialogue, bring people together, and facilitate these critical discussions.

Christian. Ethiopia needs more dialogue, but unfortunately, its media is severely underdeveloped, highly partisan, and generally amateurish. The level of propaganda, spread by nearly every faction, is often so outlandish that one wonders how people even believe it. These hyperbolic narratives only serve to inflame tensions and deepen polarization.

Ethiopia's lack of objective, high-quality media has also had serious consequences. For example, when atrocities began occurring in Tigray, there was no shared understanding of the events. Many people buried their heads in the sand because there was no established culture of objective journalism — no arbiters of truth that the public could rely on.

The polarization and horrors of the war stem from multiple factors. Still, one significant issue is the tendency among Ethiopians — across all estates, factions, and ethnic groups — to engage in self-aggrandizement, mythical nationalism, and chest-thumping. Some of this is a product of Ethiopia's violent past. Still, there are very few platforms through which people can have meaningful discussions and form informed opinions. However, despite the deep divisions, common threads still unite Ethiopians.

However, despite deep divisions, there are still common elements that unite people in Ethiopia. Most people, including urban elites, are not eager to return to the past. There is a growing recognition that Ethiopia is not just composed of Christian highlanders but is home to dozens of ethnic groups, each with unique characteristics and contributions to the nation. Political views may differ, but these divisions have not been able to erase the common threads that connect Ethiopians fully.

There is still a basis for hope and the potential for a better future among ordinary people, many of whom are ethnically mixed, multilingual, or share cultural overlaps.

Footnotes

- ^ The Dergue regime (1974-1991) was a communist regime that came with the creation of the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police and Territorial Army to overthrow the regime of Emperor Haile Selassie. It was led by Mengistu Haile Mariam.

- ^ Under the Constitution of 21 August 1995, Ethiopia is reorganised into nine ethnically defined regional states (or kilil): Afar, Amhara, Benishangul-Gumaz, Gambella, Harari, Oromia, Somali, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region, Tigray; with two separate self-governing administrations: the capital Addis Ababa and, since 2004, the city of Dire Dawa with special status.