Sashko Protyah is a director and activist from Mariupol and a co-founder of the Freefilmers group of artists and filmmakers. His works explore such themes as memory, othering and alienation. Sashko currently lives in Zaporizhzhia where he supports IDPs and the Ukrainian army as a volunteer.

Sashko’s new film My Favorite Job, 2022 tells the story of Ania and Yura, who joined a grassroots self-organized initiative of drivers that traveled between Zaporizhzhia and Mariupol to evacuate people. The film can be viewed for free from anywhere in the world during the feminist film festival Filma taking place between November 24 and December 9.

Yulia: My Favorite Job, 2022, the first film you shot after February 24, is dedicated to people who left their previous lives behind to save others. Given how your own life has changed, this is probably no coincidence. It seems to me that your creative output from before the war can be encapsulated in the verb “to understand”, and this includes shooting/watching films to understand certain things. This word is still a part of your vocabulary, but I think that in 2022, your key verb is “to help”. How do you feel about this change, and how did it affect your interaction with life through cinema?

Sashko: I haven’t yet been able to get an outside perspective on how my position as a director or viewer is changing. There’s something narcissistic about watching or shooting films just to exercise your capacity for understanding. These days, I distrust the narcissistic worldview. I do not think it’s right to place any self, my own or that of someone else, at the center of it all. Besides, it transpired that the process of accumulating intellectual expertise is generally unreliable. This process of observing, editing, drawing conclusions, promoting new ideas has always been quite Eurocentric. Today we see that the intellectual store of these experiences (of understanding, editing, observing) is of little use to us. All these intellectuals who seemingly always know best turned out to be of little help. They probably should have admitted that there was something wrong with their understanding of the world.

As for “helping”, currently I have a lot of material ready for editing. My Favorite Job, 2022 will be part of a bigger film. I chose to put this piece together first because it’s important for the volunteers, who are going to the East and South to help people. I believe that Ania and Yura’s story enables us to understand what’s going on. So this is how I combine those two verbs, “to help” and “to understand”.

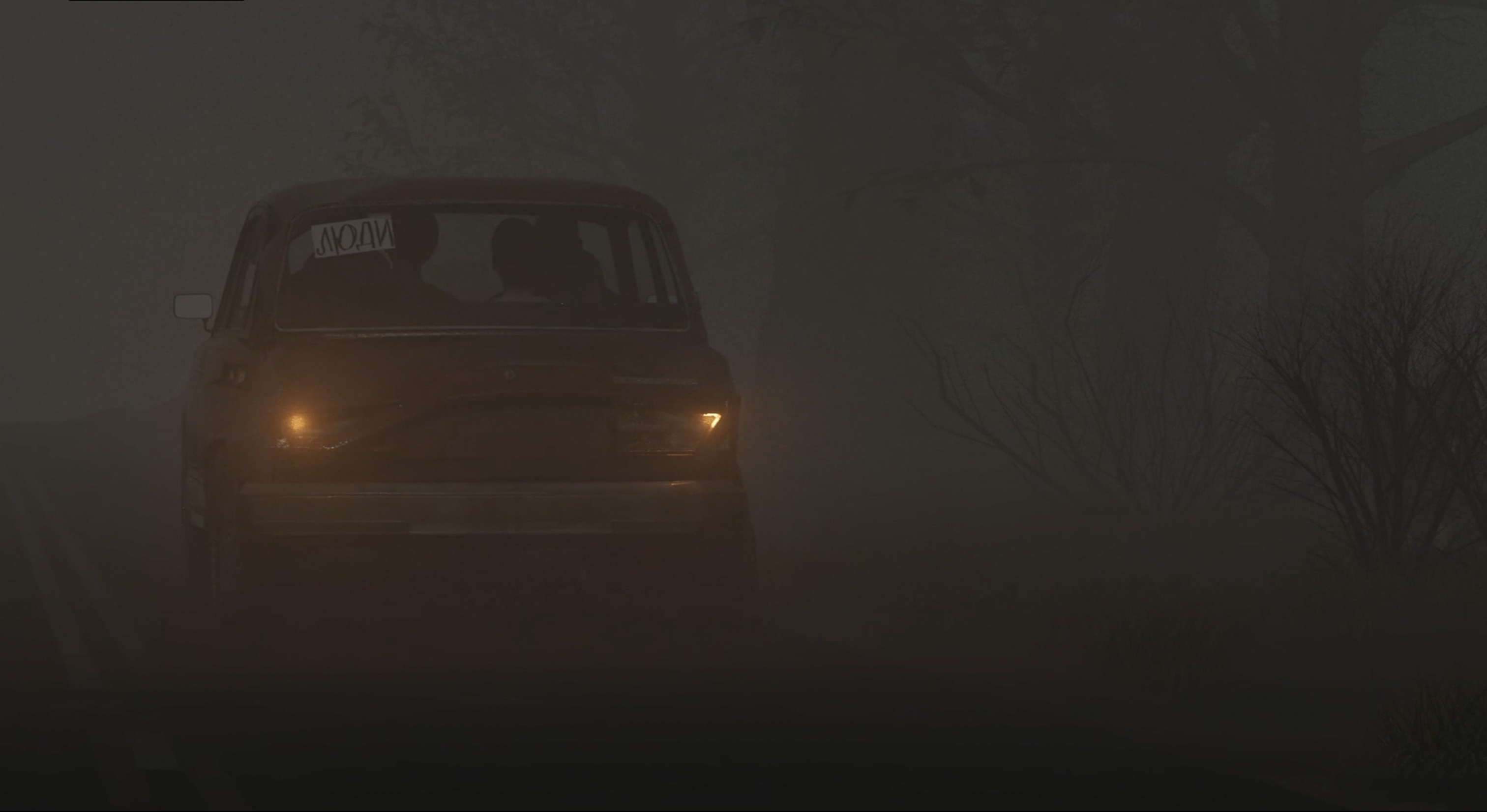

A frame from the Sashko Protyahʼs film «My favorite job, 2022»

Yulia: You often describe your experiences in cinematic terms. For instance, you told me once that this grassroots movement of drivers traveling from Zaporizhzhia to Mariupol to evacuate their loved ones is probably the most important movie happening anywhere in the world right now. Six months have passed since then. What’s the most important movie you have watched during this time?

For many of us, cinema has become a kind of instrument for understanding where we are, what we are, what happened and how it can be perceived. It’s like we have some kind of home cinema in our heads now and can screen our private inner movies there. It has already become a part of who we are.

Before February 24, my plan was to finish writing all those confounded grant applications and spend a couple of weeks watching movies I had long wanted to see. By some miracle, my selection of coveted films has survived, preserved on some cloud service. I found it at the end of August. Since then, I have only watched one movie, Oleksandr Koberidze’s What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? It’s a film about football, atmospheric coffee shops, romance and mysticism: in short, things I really dislike. Oleksandr Koberidze has made a very beautiful film about things that immediately bore me in everyday life. I enjoyed watching the movie in my inner cinema [laughs].

Yulia: Building on what was said about experiencing life as a film, I would like to ask you the same question you addressed to Ukrainian women directors during the discussion that took place as part of the festival:

“In Izium, I happened to record a conversation with a woman who survived the five-month occupation. She described her experience as a movie. Talking to people from Mariupol who experienced the blockade, I also heard this comparison more than once. What does it mean when reality feels like cinema? What can working with cameras and editing mean in a life experienced as a movie?”

A long time ago, a friend of mine admitted that she could reconcile herself to a traumatic experience if she saw it in a movie – or saw it as a movie. At the time when I heard this, in 1995 or perhaps 1996, I was not interested in cinema at all. I never watched any films. Somehow, though, the conversation stuck in my memory. And then it suddenly came back to me when I met that woman in Izium. I would like to explore this and learn more, but yes, in general it seems that cinema can be a means of overcoming and making sense of certain experiences. We can imagine this “inner movie” that someone watches, changes, edits and so on to deal with adversity.

Personally, though, I still see a line between what can become a real movie, a film you can show to other people, and my private inner cinema.

A frame from the Sashko Protyahʼs film «My favorite job, 2022»

geo: In My Favorite Job, 2022, you use 3D animation. Can you tell us why you decided to use this technique in certain episodes and how you chose them?

Already in the spring I realized it would be very difficult to find any material that could be used to show what was happening on the road between Zaporizhzhia and Mariupol, at the checkpoints and along the highway.

I tried to look for dashcam videos on the Internet, but, of course, using dashcams was out of the question, and just having a camera could cause real trouble. I couldn’t even find videos made by the occupiers. Then I realized that this experience could be related as a narrative transformed into a myth: about those who go to places where nothing remains, not even mobile signal, and rescue people, get them out. The story defies imagination, so I felt it needed a mythological element, an air of unreality. Right from the start, I knew that Vova Morrow’s drawings and NFNR’s music are just the thing to create that kind of atmosphere. I did not interfere with Vova’s process in any way apart from sending him some references. Vova then found other references and represented it all very faithfully. There was just one scene where, in a fragment done by Vova, the Epitsentr hypermarket was on the wrong side of the road; that was the only change we made. I have absolute trust in Vova as a graphic artist. With his art and Olesia’s music, I think we managed to accurately recreate this mythic experience: that I knew people who went nowhere, spent some time there and got others out.

geo: The scene in which you are “driving” a wrecked car… for you, what is it about?

We did not record the moment when Yura first told us the story of the phone call he got from the “DPR authorities”. We couldn’t go back and say, “Yura, can you tell us one more time how it all happened?” While shooting the film, this was a fact we already knew: that Yura had received a call from some DNR guys saying that he was convicted under their patently absurd laws. The very fact that he got this call is extremely grotesque, it’s like a meme that came to life. I was itching to illustrate this call. I imagined myself pitching a script like that to some elite fund that finances film production, and how people there would quickly see who I am, and look at me like I am a complete moron. It’s this kind of trickster-like moment. Yura was playing a very dangerous game with some complete morons, and I was just walking around Zaporizhzhia, saw this wrecked car and asked my friend – we went for a walk together – to film me improvising. It probably shows how I feel in the world of big cinema, big projects and big ambitions. I pull into their parking lot in a car like that, and this is how it all looks [laughs].

A frame from the Sashko Protyahʼs film «My favorite job, 2022»

Ira: Towards the end of the film, there’s a scene where Ania talks ironically about “money-attracting practices”. For me, this ironic phrase encapsulates the stigmatization of women’s practices born out of systemic issues of poverty, discrimination and capitalism. This stigmatization, in its turn, enables even more dangerous narratives while reducing the space of empathy and support. The dialogue we hear in the scene is very important and shows the incredible work done by Ania and the rest of the team to find the resources they need to help people. But I can’t shake the feeling that irony is not the most empathetic tool for making sense of extremely painful and systemic problems. What do you think about this episode?

Ania has a good grasp of contemporary popular culture: fashion trends, the beauty industry, and the professional opportunities that exist in this area. At the same time, I would say that she is a feminist (although I never heard her use the word “feminism”). We had several conversations about sexism and the way it manifests among volunteers, about the fact that some drivers resented her leadership. In my opinion, what Ania says about “money-attracting practices” is not misogynistic, it’s a joke about an environment she knows very well. She speaks from a position of irony, not hatred. This irony highlights the fact it’s impossible to explain the powerful grassroots volunteer movement, with people from vastly different social strata volunteering together and supporting each other, through stereotypes. Ania jokingly offers a stereotypical explanation suggesting that all this volunteer support was only possible thanks to the “rituals of attracting volunteer help”. But it’s just a joke. What Ania managed to achieve was done in defiance of stereotypes, thanks to volunteers’ unity and hard work. In the film, you can see that Ania rises above stereotypes and surpasses all stereotypical notions. And she knows that. She is aware of the injustices of life, so coming from her this joke is not misogynistic. It’s an ironic reference to a misogynistic perspective that has nothing to do with her and what she is doing.

All in all, I think it’s better to talk about this with Ania herself.

A frame from the Sashko Protyahʼs film «My favorite job, 2022»

Yulia: The screening of My Favorite Job, 2022 during the Filma festival is, in fact, the film’s world premiere. How do you see the film’s future?

Since the start of the full-scale invasion the Freefilmers team has received numerous offers from grassroots groups around the globe to organize “solidarity screenings”. Tell us about this mycelium of mutual support we have become a part of this year.

In recent years, “big” documentary film festivals have often held discussions about alternative methods of film distribution, but these conversations frequently go nowhere: despite the obvious crisis of the classic methods of film distribution, no alternative that could be capitalized on has yet been found. How can we shoot and watch movies on the fringes of global capitalism?

In the spirit of true democracy, I thought that later (after Filma) the film could be made available on the Freefilmers YouTube channel.

Frankly, I don’t understand why I should give a damn about what’s being discussed at the big festivals, like why they need to come up with new, alternative forms of distribution. I don’t care what they think. In my opinion, paying attention to these so-called industry leaders’ plans on how to save their industry is pointless. I’m not interested. At the beginning of March, virtually on the same day, we were contacted by WET Film, Freefilmers’ close friends from Rotterdam, by our friends from Slovakia and by the Estonian platform electron.art. They suggested organizing screenings to support our community and instinctively started calling them “solidarity screenings”. Then this mycelium of support began to grow. There were many similar events, all designed for small communities. In general, everything was done exactly the way we have always showed movies ourselves: we would come to some place, have twenty to forty viewers (at most) show up and hold a discussion after the screening. Of course, the solidarity screenings differed from the events we ourselves used to organize: crucially, none of us could be there. People gathered, watched our films – they chose the films themselves – and showed their solidarity in different ways. We often got donations of 50-60 euros from small towns. Sometimes small art centers paid us a modest fee when they screened our films. What really impressed me was one of the most recent events, in Wales: people from a town that used to have a small-scale factory (closed during Thatcher’s rule) gathered to think about the East of Ukraine. Thatcherites promised the town prosperity and built a high-tech park there, but today everything is in a state of collapse. People live among the ruins, the remains of the infrastructure. And they got together to watch our films and see works produced by photographers from eastern Ukraine. It was an event of the greatest imaginable solidarity: these people from a poor town, many of them probably unemployed, wrote fifteen letters of support and collected funds. Some of them were unable to use online payment systems, so they simply handed over cash to the organizers. They also made some cool prints, and the poster was not only in English, but also in Welsh. This screening had nothing to do with festivals or the art industry. Throughout this time, we were contacted by festivals on a couple of occasions only, and those festivals who did contact us quickly realized that it’s difficult to slot us into a familiar category... Once we were asked, “Are you connected to Docudays?” When we said no, the correspondence came to an end.

Merch developed in Wales for screenings of Ukrainian cinema and photography

The network of grassroots initiatives critical of the capitalist system – initiatives that exist in the spheres of culture and art, activist movements – has grown a lot in our country during this year. There are many regions of the world we still have no communication with, but in time, I hope, we will be able to reach out to filmmaking and other communities abroad. They have their own experiences of resisting capitalism and innovative ideas on how to create art that cannot be turned into a tool of colonial subjugation and exploitation. It would be good to see this mycelium grow.