This article was written as part of the work of the economic department of Center for Social and Labor Research.

“People get, for example, a degree in law, and then get a job at McDonalds. But they could have worked there before receiving their diploma, and the country could have saved 800 hryvnias on them.” This sort of thinking is popular among Ukrainian reformists and was voiced by the president of Kyiv School of Economics, Tymofiy Mylovanov at a press conference dedicated to cancelling stipends/scholarships for most of the students.

This expert thought perfectly illustrates a very mercantilist approach to education, where education has a defined purpose — to prepare workforce for the labor market. According to neoliberal logic of profit maximization, such functions of education as providing upward social mobility and allowing inclusive personal development are not important, as they do not fit the slim model of macroeconomic balance.

If we applied this logic, we would have to close at least 80% of Ukrainian universities and provide scholarships for the top 10% of the smartest students. Bursaries for children from poor families should not even be taken into account, as these children would most certainly lose to their peers from wealthier families, and, after all, someone has to work low-skilled jobs. The question is how forward-looking this approach is (especially in the global context of modernization of economy and technological development), and what kind of society we are trying to build this way.

This article differs from the others we produced where we used detailed and rational empirical data and analysis of the situation of the universalization of higher education and industrial automation. Here, we are trying to look beyond the capitalist reality and we allow ourselves to reflect upon what mechanisms could stimulate positive changes in social development. Apart from that, we ask ourselves a question: how can social institutions of education and economics coexist in the future, granted that humanity would move away from the logic of owners’ profit maximization and focus on meeting the needs of all people? Some might say that these reflections are nothing more than speculation, but how else can we plan better future without constructing an image of how it should function?

What is the labor market coming to?

If we move away from Ukrainian periphery realities to the broader global context, it is easy to notice that technological development transforms the production process. Japanese robotic factories FANUC function without human labor since 2001. The robots create around 50 other robots in their 24-hour shift, and they can work without maintenance for up to 30 days (Null & Caulfield 2003). In the Netherlands, Philips produces electric razors using 128 robots. The only people on the factory are nine workers that control the quality at the end of the production process. Automation has even reached a rather new field of sharing economy. Recently, a transport company called Lyft (an Uber alternative) announced that they plan to introduce self-driving cars into their carpool in 2017; therefore, the need for taxi drivers would disappear.

Using robots to perform routine tasks has moved from science fiction to reality long ago. Nowadays, the profit it brings in is proportionate to increase in computing power of microchips. Advances in digital technology multiply the number of forms and mechanisms of communication, enabling remote execution of increasingly wider range of operations and geographical dilution of production staged among the regions of the world.

In these conditions, what happens to the labor market? Research shows that, at this stage of technological development, automation is the biggest threat for middle-level workers. It is unprofitable to automate cheap labor, and so far, it is not possible to replace better-paid high-skill labor with technology, as it requires creative thinking and the ability to react to events in unpredictable conditions.

Moreover, automation moves at a faster pace in core countries that are more technologically developed and have higher wages (Citi & Oxford Martin School 2016, 26). At the same time, (semi-)periphery societies still exploit the rundown means of production and sell their cheap workforce to other countries, choosing to attract foreign investments rather than to modernize the production and improve efficiency.

Even now, the technological progress in market conditions has many side effects, such as creating new mechanisms for outsourcing cheap labor from periphery countries, polarizing the occupational structure, weakening of trade unions and social protection of the workers, fragmenting of the work and distributing unstable precarious employment (Dyer-Witheford 2015, 135). Increased competition for low-paid work devalues it even more, whereas the salaries of those who occupy the top of income distribution only grow due to increased demand for highly skilled workers (OECD 2015).

Despite the significant progress in the development of technology, we would not be seeing automated trains or robotic factories in countries like Ukraine any time soon. Contrary to the popular idea that "neoliberal competition stimulates innovation development", these technological capabilities are not being used fully under capitalism. Global growth is slowing down because, in a competitive environment, the strongest competitors win, while weaker players are left behind the modernized world.

However, given that workforce cannot get that much cheaper, the gradual decrease in value of technology over time would cause automation and computerization to become more cost-effective compared to human labor. In turn, this would lead to higher unemployment rates and even more catastrophic deepening of the inequality between different socioeconomic population categories. Moreover, the inequality between different regions of the world would also grow. It would not be beneficial anymore for core countries to create workplaces in poor societies, which would shake the already unstable peripheral economy that depends on western investments. Poorer countries would a priori lose to advanced countries with much more effective automated production.

Such unnerving forecasts stimulate the search for mechanisms that could work as a potential neutralizer of side effects of technological development. After a rather lengthy description of the state of the labor market in technological development conditions, it is time to move on to the institution of education.

What is education capable of?

Risks of automation actualizes the question of what to do with workers whose employment would be unprofitable and who would not be able to compete for a high-paid work due to lack of qualification. In this case, greater access to education could be one of the mechanisms of lessening the negative effects of automation. In addition, it would cause such positive societal changes as reduction of social and economic inequality and create the conditions for inclusive development for a wider range of people.

-

Improving the level of competence

The ability to perform basic operations needed for the functioning of society (e.g. production and transportation of necessary goods and services) in a more effective and efficient way would allow to free up the resources for scientific and technological development, and for solving social problems. As the research on the labor market shows, economy in general would require higher competence in creative intellect (the ability to generate new ideas), social intellect (the ability to understand the social and cultural context), perception and management skills (the ability to react to events in unexpected circumstances) (Citi & Oxford Martin School 2016, с. 19).

In this context, greater access to higher education would allow to retrain lower- and mid-level workers to perform more intellectually challenging tasks. It is also important to consider that a person’s life is not limited to their employment. Therefore, institution of education should not only serve the labor market but also create conditions for the inclusive development of personality, cultivate analytical skills for understanding and processing complex information, and provide opportunities to fully participate in the various areas of public life. This could stimulate the generation of innovative approaches to solving problems and promote positive social change, increasing intellectual potential of humanity.

-

Improving the socio-economic situation

Contrary to popular belief that, detached from the labor market, higher education does not protect from poverty and unemployment, research on inequality shows that education level still affects the level of income. According to statistics of Institute for Demography and Social Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, among people with complete higher education, 13% are poor, 32% are of average income, and 12% are rich. At the same time, among people with complete secondary education, 29% are poor, 19% are of average income and only 4% are rich. When at least one family member has higher education, it lowers the risk of poverty by 38%; if two family members have a degree, it lowers the risk by 54%. Despite the fact that many graduates do not work in the specialty they trained in, they are more competitive on the labor market, have a lower risk of losing their job and are able to find a new job much faster (Libanova 2016).

Based on the statistical data, it can be said that, even in the Ukrainian context, investments in expanding the access to higher education would improve the socio-economic status of people and allow citizens to get high-paying jobs in current economic system. However, such conclusions would be too naive if we do not take into account the current conditions of the labor market. Under fixed conditions, increasing the access to education would have a positive effect from the macroeconomic point of view to a certain limit, until the labor market is filled with highly qualified labor force. In today's economy, to get a job, you must have a diploma. Nevertheless, the possession of the diploma does not guarantee you would get a good job. Increase in the number of diplomas without the corresponding expansion of the labor market only increases the competition for the same jobs.

As David I. Backer aptly notes in his article The False Promise of Education, “Better education won’t fix inequalities rooted in capitalism… Schooling cannot control the number or kind of jobs available in an economy. For the last decade, for example, it was probably a good idea (in terms of potential income) to study petroleum engineering as an undergraduate. Today, given the dramatic fluctuations in oil prices, it’s perhaps not such a great idea. No matter how many people study petroleum engineering, or how good petroleum engineering education gets, it’s the petroleum industry and its fluctuations that determine how many jobs will be available and their respective salaries.” (Backer 2016).

That is why the appropriate educational policy should be accompanied by investments in modernization and development of more intellectually demanding manufacturing sectors. For (semi-)periphery countries, it would most likely to contribute to economic growth rather than to preservation of cheap labor to attract foreign investments. Moreover, it would reduce the risks of the growing gap in competitiveness with core countries in the further automation.

-

Reducing unemployment rates

Using higher education as a mechanism for neutralizing negative consequences of automation makes sense even in the short term. According to Randall Collins, an American sociologist, in modern society, access to education is significantly ahead of the situation on the labor market, creating the inflation of diplomas. One can argue with the researcher about whether this process is inflation or social mobility. However, there is no doubt that the educational system plays a crucial role in absorbing the labor displaced from the labor market. Temporarily holding people from entering the labor market and facilitating their stay in the same environment, education reduces unemployment, and provided the students receive financial support, it can even be considered a hidden system of social protection (Collins 2002, 232).

In addition, broader access to education stimulates demand for researchers and teachers. Therefore, attracting more people into higher education makes this sector one of the main employers in the service industry (Edu-Factory Collective 2009). If the manufacturing process using technology increases productivity, the education sector retains its low productivity growth, as teaching is a laborious process that cannot be fully replaced by technology.

Of course, such social changes require a substantial increase in public spending on education. However, according to the American economist William Baumol, increased investment in education is not a big problem in economic terms. It can be compensated by increasing the productivity of other economic sectors due to automation (Baumol, 2011). One would like to think that in the society of the future we would work on improving the efficiency of the economy to provide wider access to education, and not look for the ways to save on education expenses, focusing on the preservation of cheap labor to attract foreign investment.

-

Providing mechanisms for direct democracy

Broad access to higher education is also important in view of the possibility of using technology to ensure the mechanisms of direct democracy. With the high level of education, incompetence of the public in decision-making would no longer be a problem. As long as the educational institution not only transfers the knowledge, but also instills the skills needed for search, filtering and critical analysis of information.

This is why it is important that educational programs not only focused on the constantly changing trends in the labor market, but also integrated general subjects intended for inclusive development of the personality and critical thinking skills. Very fitting here is the title of the Times Higher Education article, Donald Trump’s victory shows why we need philosophy students more than ever. “We need to make America think again”.

We need to make the world think. Technological development opens up the possibilities that we could only dream of. Equitable distribution of resources, including access to education that would meet the needs of everyone, could create a fairy tale in which all people have unlimited access to knowledge, are engaged in interesting, creative and socially useful work and consciously involved in managing reality. The question is, what principles should be used in socio-economic relations?

What education will save the world?

The idea of stimulating economic development through investment in education not only in the core countries, but also in the (semi-) periphery countries has moved beyond the 'left-wing populist appeals'. For example, when analyzing the potential outcomes of automation, economists at Oxford University noted, "because skilled jobs are substantially less susceptible to automation, the best hope for developing and emerging economies alike is to upskill their workforce." (Citi & Oxford Martin School 2016, 19)

Of course, in this case it is necessary to understand that expanding access to education without creating suitable jobs would not be enough to stimulate the economy. It is equally important to identify which mechanisms of educational policy could contribute not only to training skilled workforce, but also to reducing social and economic inequalities and building a more just society.

Although the institution of higher education has lost its elite status and is becoming more accessible to wider groups of the population, access to it still depends on socio-economic origin. Given that the entrance exams require prior training, and the amount of student financial support by the government is limited, children from poor families are much less likely to get higher education and improve their socio-economic status than their more privileged peers. This is attested by research of core countries (Devine, 2004) and (semi-) periphery societies as well.

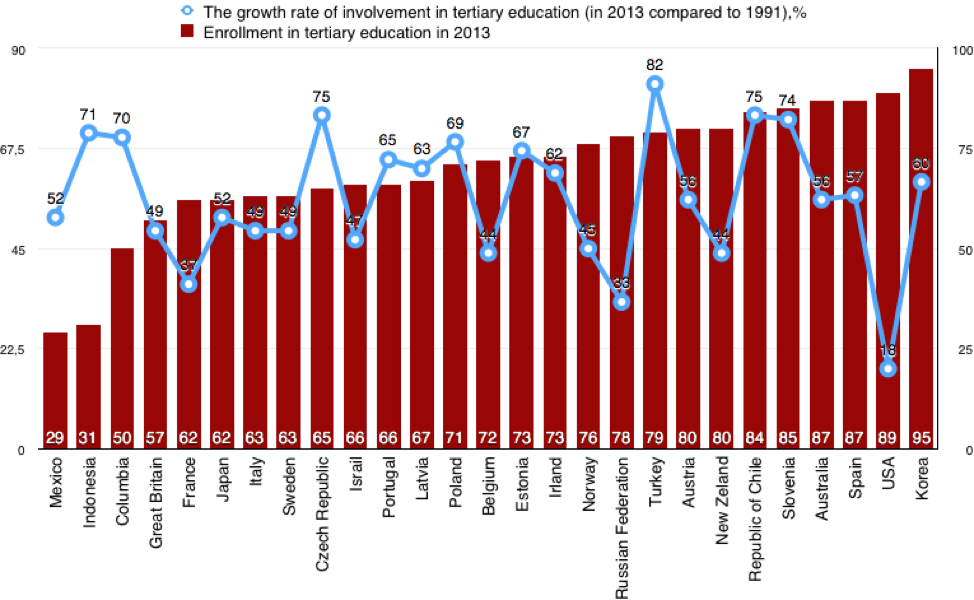

Figure 1. The growth rate of involvement in higher education (2013 vs 1991), % (personal calculations using the data from UNESCO Institute for Statistics).

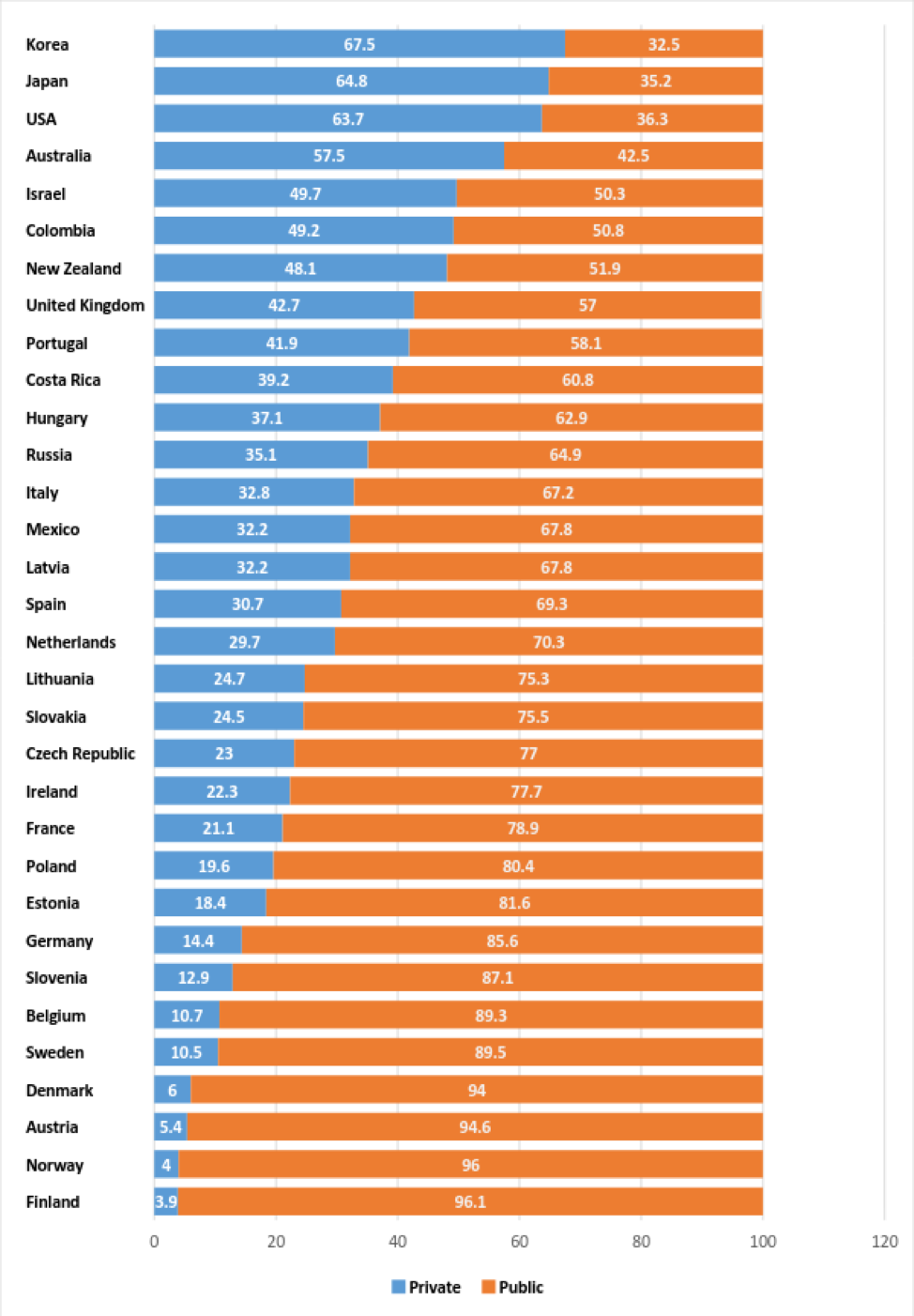

Figure 2. Expenses on higher education (data taken from OECD)

In general, the level of involvement in post-secondary education in core and semi-periphery countries has been growing rapidly for the past 20 years, and in most OECD countries it has passed the 50% mark (of the corresponding population category) (Fig. 1). However, the expenses on higher education in most OECD countries and their partners are not fully covered by the state (Fig. 2). The largest share of public expenditure on higher education is observed in the Nordic countries, as well as in Austria and Germany.

In turn, in more liberal countries like the US and UK, as well as in the eastern countries with rapidly growing economies (Korea, Japan), the higher education cost structure is dominated by private funds. According to an American sociologist Craig Calhoun, the higher education sector in the United States after World War II (and especially in the 90s) grew largely because of private capital, accompanied by opening of private schools and rising cost of educational services: “Higher education has never been cheap, but it has become much more expensive. Tuition has risen not merely at the rate of inflation, but more or less at the rate of increase in luxury car prices. Of course, tuition is still subsidized at public universities — though states are bearing less and less of the proportionate cost. Michigan pays only perhaps an eighth of the cost of the University of Michigan.” (Calhoun 2006)

If the Scandinavian countries, the US and Great Britain represent certain ideal types of market and social-oriented educational models, for other societies it is common to combine elements of both approaches. However, under the conditions of austerity policy, mechanisms of commercialization of education and better targeting of state financial support become more common, as they justify belt-tightening during the crisis. Although for (semi-)periphery countries such a policy is more like noose-tightening around the neck. In the context of modernized economy of core countries, reliance on cheap labor can only work as a temporary lifeline to attract foreign investment, which would eventually lose its profitability to proportionate cheapening of technology.

In the same way, the policy of limiting access to free higher education and better targeting of financial support for students that is being implemented in Ukraine would not facilitate further training and withholding the workforce from entering the labor market, meaning that people would not be able to find employment in the future because of automation. Given that routine work involves people from less favorable socio-economic environment, the commercialization and increased competition for financial support of university studies is not likely to improve their socio-economic status and personal development.

The expansion of the education sector by increasing the share of private investments also contributes to strengthening of 'fair' competition among universities. In Ukraine, it is stimulated by a new targeting allocation mechanism of state-funded places in universities called 'voucher system'. The state-funded student places in universities with high-ranking applicants (those who received the highest scores on their external independent evaluation (EIE) tests) increased by 25% in 2016 vs 2015.

While competing for limited state funding and student wallets using the standard neoliberal scheme, those who already have the resources are able to accumulate even more, when those who initially were less privileged can retain the status quo at the best of times. As the US experience shows, this strategy leads to greater hierarchization of the educational system. This does not solve the problem of educational inequality, but only changes its structure, transferring the demarcation line from the fact of availability/absence of the diploma to the stratification by having an Ivy League diploma or a mediocre university's one, as well as the amount of obtained degrees (Calhoun 2006).

In addition, there is a question of whether online and offline courses can replace a full-fledged higher education in acquiring different skills. For example, why cover the whole tuition fee at a university for a former factory worker if such worker can be trained through a three-month programming course? From a mercantilist point of view on education, it makes sense. Although, again, this paradigm leaves out the much broader functions of higher education such as personal development and neutralization of inequality.

Three-month programming course can hardly teach the attendee to perceive and critically analyze information. Moreover, as shown by current educational research, education neutralizes inequality at least due to the fact that people from different socio-economic groups spend time in the same environment, perceive the same information and build social connections, which greatly improves their life chances compared to a situation when they remain in their typical environment (Downey & Condron 2016).

Lower symbolic importance of certificates of completion compared to a university diploma reflects social and economic inequality on the labor market, making the certificate holders less competitive compared to those who were lucky to graduate from university. Moreover, even in universal higher education conditions, the problem of inequality in access to skilled labor cannot be solved by just holding a piece of paper certifying the completion of university studies; it is only transferred to another area, i.e. competition among these pieces of paper for their symbolic meaning.

For a paper to have not only symbolic but also real meaning, education must be of high quality. The main factor of legitimizing the unpopular education reforms in Ukraine is the low quality of education that leaves no doubt about the need for change. The question is, what changes should be made? It is inherent for the liberal approach to education management to be convinced that expanding access to education leads to degeneration of its quality. After all, if all children are able to enter a university after graduating from high school, it would not be possible to select the best (= those with better social and economic conditions for pre-entry training), consequently, universities would have to teach the weaker students as well.

Overall, perceiving the quality of education through quantitative criteria of average scores, test scores and academic ratings reflects the neoliberal logic of competition and hierarchy in terms of education commercialization. Universities are not willing to accept poorly prepared students, as it would reduce their rating, making them less competitive compared to others, dent their great brand, and, as a result, attract fewer students that pay tuition fees and potential investors. States invest in more successful universities to get them even higher in the international rankings.

Thus, we can see the same logic of cost minimization and profit maximization, as well as a commitment to reward the most successful resulting in producing and reproducing social and economic inequality. At the same time, real problems of the universities that the invisible hand of the market cannot solve are still being ignored. For instance, an extremely low level of capital expenditures to support universities in Ukraine makes it difficult to maintain comfortable temperature in classrooms, renovate the premises, purchase modern equipment, new literature and access to online resources.

Could it be otherwise? As experience of the Bolivarian University of Venezuela shows, higher education can be very open, focused on attracting people from different socio-economic environments and aimed at solving social problems. The only question is which social goals we set and what methods we use. For example, to encourage involvement in the education of different social groups the pedagogy of Paulo Freire can be applied. In turn, the even allocation of resources among universities can be stimulated through targeted funding of weaker institutions aimed at identifying and solving existing problems.

New technologies produce new opportunities, as well as new challenges that cannot be solved using old economic anti-recessionary measures (by increasing demand or reducing the expenditures). These problems stimulate the search for new alternative approaches to solving them, leaving hope for a change in the logic of public relations in favor of meeting the needs of the majority and reducing socio-economic inequality. Institution of education is one of the mechanisms to neutralize negative effects of technological development in the society of the future, a transition to which should be accompanied by the global transformation of the functioning of public institutions that reproduce inequality. However, it is a good way of defining the existing problems and desired changes. What can we do now in terms of total domination of market principles in all spheres of social life? We should at least seek the root causes of the current problems and dream about the future. In the words of Victor Hugo, "there is nothing like a dream to create the future."

References:

Aimar S., Egan D. (2016) “Donald Trump’s victory shows why we need philosophy students more than ever”. Times Higher Education.

Backer I. D. (2016) The False Promise of Education. Jacobin.

Baumol, W. J. (2011) Toward Prosperity and Growth. Kauffman Thoughtbook.

Calhoun, C. (2006) Is The University in Crisis? Society, 43 (4). pp. 8-18.

Citi GPS: Global Perspectives and Solutions. Technology at work v2.0. Oxford Martin School (2016) University of Oxford.

Collins, R. (2002) Credential Inflation and The Future of Universities. The Future of The City of Intellect: The Changing American University, pp. 23 —46.

Devine, F. (2004) Class Practices. How Parents Help Their Children Get Good Jobs. Cambridge University Press.

Downey, D. B., & Condron, D. J. (2016) Fifty Years since the Coleman Report Rethinking the Relationship between Schools and Inequality. Sociology of Education.

Dyer-Witheford, N. (2015) Cyber-Proletariat. Global Labor in the Digital Vortex, London: Pluto Press.

Edu-Factory Collective (ed.) (2009) Toward a Global Autonomous University: Cognitive Labor, The Production of Knowledge, and Exodus from the Education Factory. New York: Autonomedia.

Libanova, E. (2016) Ukraine: The Depth of Inequality. ZN.UA.

Muliavka, V. (2015) The Bolivarian University of Venezuela: a Radical Alternative in The Global Field of Higher Education. Commons: Journal of Social Criticism.

Muliavka, V. (2016) Why Public Education Is Unequal: Case of Ukrainian Rural Schools. Knowledge and Performance Management, 1 (1), Volume 1 2016, Issue 1, pp. 19 —26.

Null, Ch., Caulfield, B. (2003) Fade To Black. The 1980s Vision of “Lights-Out” Manufacturing, Where Robots Do All The Work, Is a Dream No More. CNN Money.

OECD (2013) Spending on tertiary education.

OECD (2015) OECD Employment Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris.

The World Bank (2013) Gross enrolment ratio, tertiary, both sexes (%).