Since the summer of 2023, the issue of educational reforms is back on the agenda. We hear about it from central and local authorities, university rectors, and the media. The “talking heads” of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, university administrators, NGO activists, Ukrainian MPs, and others talk about money that “follows the student,” about “modernizing the network of higher education institutions,” about “moving away from the system of state orders,” and other amazing innovations that, according to reformers, should finally bring Ukrainian education up to European standards.

However, as has been the case in recent years, students’ opinions on the reforms remain virtually unheard. And while the issue of university reorganization still resonates with students of the institutions that the Ministry of Education and Science has expressed a desire to merge, the reform of state funding of higher education is discussed mainly in the highest echelons of power. No one is going to ask either the current or future students for their views on this.

The cornerstone of the state funding reform is the draft law “On Amendments to Certain Laws of Ukraine on Financing Higher Education and Providing State Targeted Support to Its Applicants” (No. 10399), submitted by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine to the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian Parliament) on January 10, 2024. It is this document that sheds light on the real danger of the reform that Deputy Minister Mykhailo Vynnytskyi and other government officials have been trying to “sell” in the media for more than six months. Let us analyze several aspects of the draft law that the Ministry of Education and Science tries not to mention.

No Guaranteed Government-Subsidized Student Places

First of all, the draft law actually cancels the guarantees of the minimum number of government-subsidized student places. Currently, according to Part 1 of Article 72 of the current Law “On Higher Education,” the total number of government-subsidized students among junior bachelors and bachelors (and masters degrees in certain fields) for the current year comprises no less than 51% of the number of graduates who received complete secondary education in the current year. In other words, the number of government-subsidized student places is calculated according to the number of people who graduated from schools and cannot be less than 51% of this number. Similarly, the norm is set at 50% for masters, taking into account the number of bachelorʼs degree graduates, and for postgraduate students – 5% of the number of those who receive a masters degree.

Students in class. Photo from public domain

The new wording of this part of Article 72 does not provide any guarantees regarding the minimum number of the government-subsidized student places. It is only stated that the state order is formed by the central executive body, the Ministry of Economy, in accordance with the procedure established by law.

In other words, it is proposed to cancel any legal requirement for the minimum number of government-subsidized student places. What does this mean in practice? In the opinion of the Central Scientific Experts Office (CSEO) of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, if there are no specific requirements for the percentage of specialists to be trained, “the state order,” i.e. the mechanism for ensuring “free higher education,” may not be formed at all.

In its conclusion, the CSEO emphasized that, according to Article 22 of the Constitution of Ukraine, when adopting new laws or amending existing laws, it is not allowed to narrow the content and scope of existing rights and freedoms. Part 3 of Article 53 of the Constitution of Ukraine establishes the obligation of the state to ensure accessible and free higher education in state and communal educational institutions. The CSEO experts cite the interpretation of this provision by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine[1], according to which “free higher education means that a citizen has the right to receive it in accordance with the standards of higher education without paying a fee in state and municipal educational institutions on a competitive basis (Part 4 of Article 53 of the Constitution of Ukraine...).” Thus, the provision of free education means the state order, not the payment of tuition fees through grants, even if the grant covers the full cost of tuition.

By proposing to introduce a grant system and effectively abolish the guarantees of minimum volume of the state order for students, the Ministry of Education and Science explicitly states that 25-30% of students will study under state or regional orders (receive funding from the state or regional authorities) – the Ministry expects to achieve such figures within 5 years of the reform. In view of this, it is easy to predict that the adoption of the “grant bill” will inevitably lead to a narrowing of the scope of rights and freedoms, in violation of Part 3 of Article 22 of the Constitution. Therefore, it is not only about formal legal difficulties with the constitutional interpretation of “free” higher education or the fact that the Budget Code of Ukraine does not contain the concept of “state grant.” The changes to the legislation proposed by the government will lead to disastrous consequences: government-subsidized education will become even less accessible, and the volume of state funding may be reduced arbitrarily, at the discretion of the Ministry of Economy, without any legal restrictions.

Minister of Education and Science of Ukraine Oksen Lisovyi with his deputy Mykhailo Vynnytskyi in Mykolaiv. Photo: Mykolaiv Regional State Administration

It is also worth bearing in mind the statements of the Ministry of Education and Science that only students of certain specialties that are most needed by the state will be eligible for state or regional procurement. However, the draft law No. 10399 does not provide a list of such specialties, nor does it provide any clear guarantees regarding the size of grants or the volume of state orders (the aforementioned 25-30%). All these forecasts are supported only by financial and economic calculations for the draft law and statements by the Ministry, but not by the law. Without exaggeration, the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine suggests that we simply trust them that the amount of state orders and grants will correspond to their promises. And, of course, we are supposed to believe that the “generous” authorities will not reduce the right to free education to an absolute minimum. The proposed reforms will make such a step perfectly legal.

In Search of a Stipend

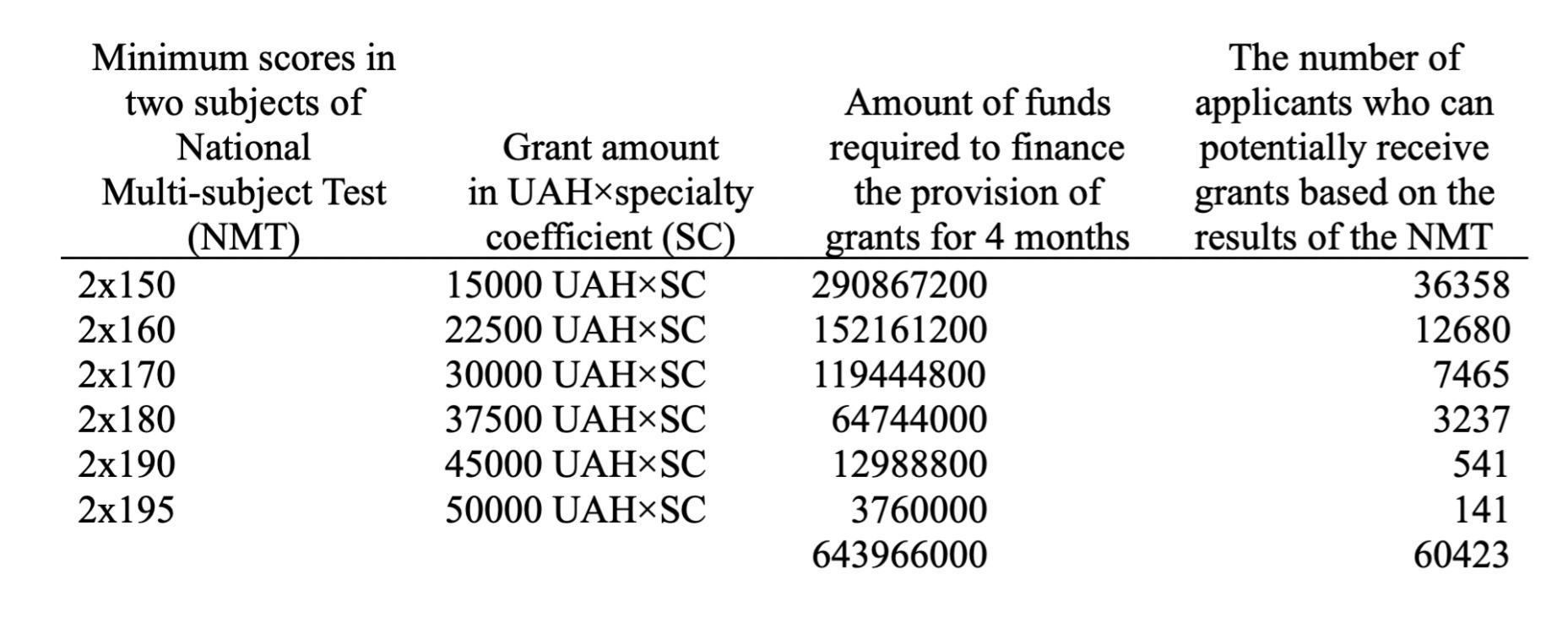

Let’s assume that the Ministry of Education and Science fulfills its promises and we are talking about the amounts of grants that they indicate in the calculations for draft law No. 10399, namely from 15 to 50 thousand UAH multiplied by the “specialty coefficient” – another innovation not mentioned in the draft law itself. However, even if an applicant successfully passes the National Multi-subject Test/External Independent Evaluation and manages to obtain a grant that will fully cover the tuition fees, they will not be eligible for a stipend.

Financial and economic justification for the draft law No. 10399

Currently, according to Part 2 of Article 62 of the Law of Ukraine “On Higher Education,” those who study full-time at the expense of state or local budgets are entitled to academic and social stipends. Of course, these stipends are rather small, and representatives of the Ministry of Education and Science openly admit this, but even these small stipends can help students with their expenses and contribute to at least partial financial independence. The draft law cancels these benefits. And although the grant, according to the Ministry of Education and Science, “follows the student,” it can only be used to pay for tuition. So even if you receive a grant that exceeds the cost of tuition, the difference is not offered in the form of a stipend – it is simply returned to the budget.

The issue of social stipends is particularly problematic, as they will not be paid to “grantees” either. For privileged categories, the draft law only proposes to establish special conditions for admission and payment for educational services. However, if a person from a privileged category receives a grant instead of a government-subsidized student place, they will not be able to receive a social stipend. In other words, the replacement of government-subsidized student places with grants will also mean a reduction in opportunities for social stipends.

In addition to the fact that the number of stipend recipients will be reduced due to the partial replacement of the state order with grants, the government proposes to introduce a new criterion that will limit the right to receive social stipends and state targeted support (coverage of tuition fees, provision of textbooks, exemption from dormitory fees, etc.). If the draft law is adopted, support will be provided only if it is necessary due to the financial hardship of the family. The criteria for determining the financial and property status of a family will be set by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. As in the case of the abolition of the minimum volume of public procurement, the experts of the CSEO emphasize that this may lead to a narrowing of existing rights and freedoms contrary to Part 3 of Article 22 of the Constitution of Ukraine. It is easy to guess that it is precisely for this narrowing – and thus outright skimping on social payments – that the government is complicating state targeted support and social stipends with additional criteria.

The position of human rights organizations dealing with the issues of IDPs and those living in the temporarily occupied territories is also interesting in this context. In their joint statement of January 31 this year, NGO Donbas SOS, ZMINA Human Rights Center, Charitable Foundation Vostok SOS and some other organizations emphasized that the criteria for IDP applicants and students would be quite strict and may not take into account the vulnerability caused by displacement – the need to rent housing, loss of access to property and, accordingly, the need to purchase new property, and the additional financial burden in general. They also noted that the draft law No. 10399 cancels the existing state support for applicants from among IDPs and residents of the temporarily occupied territories, which means no more free education through stipends for preparatory courses at Ukrainian universities. Thus, if a person wants to study in the government-controlled territory and needs to undergo additional training, including in the Ukrainian Language and History of Ukraine, they will have to pay for the preparatory courses on their own.

Forced Employment

Article 64-1 of the draft law “On Higher Education” introduces the concept of an “employment contract” that students studying under a state order are required to sign. Such agreements are completely new to Ukrainian legislation, and there are currently no rules on their content, other than those proposed by the draft law. The provisions of the draft law (Part 2 of Article 64-1) only state that this agreement must provide for employment after graduation for a period of at least three years.

The chronology of events for government-subsidized students will be as follows: upon admission, they sign a study contract, which must state that in the future, if they receive offers from an employer or a local employment center, they will sign an employment contract. It is important that at the time of signing the study contract, the applicant cannot know what kind of offer they will receive. That is, they agree in advance that they will sign a contract whose terms will become known only after half of the study period has been completed. It is then (but no later than six months before graduation) that the offer is received from the employer or the local employment center. Within one month of receiving the offer, the government-subsidized student must sign the employment contract.

Of course, a person can refuse to enter into a contract, but in this case, they will have to transfer to contract study at their own request, losing their stipend. In other words, those who cannot afford to pay tuition fees have little choice: accept the job offer or leave university. The only option provided by the draft law for withdrawing from an employment contract without losing a stipend is to enter military service or law enforcement.

If an employment contract is concluded, a government-subsidized student gets an advantage: for the remaining time of study, they will receive an increased academic stipend, which is promised to be set at the level of the minimum wage. Again, there is no hope for anything more than promises: the draft law does not even set out the approximate amount of the increased stipend.

A meeting of the Board of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, October 19, 2023. Photo: Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine

So, if a student has managed to get into a state or regional program, they must then work for a certain employer, which can be not only the state but also private individuals, for at least three years on the terms and in the position set by the employer. If a person fails to fulfill or improperly fulfills the employment contract, they will have to reimburse the state or local budget for both the cost of education and the promised increased stipend. Interestingly, the Ministry of Education and Science used to reject the idea of such “compensation work.” For example, the Ministry’s Letter No. 1/9-309 of June 26, 2015 states:

“The obligation to compensate through work or reimburse the cost of education by a graduate violates the constitutional right of a citizen to work, freely chosen or accepted by them (Article 43 of the Constitution of Ukraine) and the right to free higher education in state and municipal educational institutions (Article 53 of the Constitution of Ukraine), contradicts the obligation of the state to abolish compulsory labor and not to resort to any form of it as a method of mobilizing and using labor for the needs of economic development (Article 1 of the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, No. 105, ratified by the Law of Ukraine No. 2021-III of October 5, 2000).”

It seems that for the new representatives of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, the provisions of the Constitution and international obligations no longer play a major role, so they have nothing against ignoring them.

At the same time, it is important to keep in mind the ongoing labor law reforms, including the new draft of the Labor Code, which is marked by a course toward further deregulation of labor relations. The system of forced employment proposed by the government will go hand in hand with these labor reforms; together, they will lead to the precarization of young workers. The new version of the Law “On Higher Education” will send them to work for 3 years to earn their “ government-subsidized student place,” and the new Labor Code will allow employers to dictate working conditions at their own discretion, without being bound by the standards and restrictions set by the old Labor Code. So instead of offering help to students to find their first job in their field, the government is offering help to employers to find labor.

“Let It Be Worse, but Different”

In addition to the position of human rights organizations and the comments of the CSEO on possible violations of the Constitution, the Trade Union of Education and Science Workers of Ukraine also opposed the draft law, calling for its withdrawal from consideration. Despite this, the Verkhovna Rada Committee on Education, Science and Innovation gave it a favorable assessment.

The arguments presented by the MPs boiled down to “let it be worse, but different”: despite the comments on the obvious problems of the draft law, the Committee members came to the conclusion that there were no alternatives. To quote Roman Hryshchuk, “we are either leaving this system now, realizing its imperfection, or trying to do something with the already proposed draft law, there is no third option.” It seems that the MPs believe that the imperfection of the existing system is a justification for introducing anti-social reforms that, among other things, may lead to a violation of the Constitution.

Student protest against the merger of Taurida National University with Kyiv Mohyla Academy, January 25, 2024. Photo: Dmytro Mazur, student and activist of Direct Action

The MPs demonstrated a complete inability, or rather unwillingness, to take into account the opinions of students and educators when considering the draft law. The Expert Council of Students, which operates under the Education Committee, did not present its position, and the appeals of activists of the independent student union Direct Action obviously went unheeded by MPs. Although the head of the subcommittee on higher education, Iuliia Hryshyna, mentioned the position of the trade union of educators, as well as the outrageous nature of the system of compensation work for state employees, which, according to her, did not work even in the Soviet Union, this did not prevent her from voting in favor of the bill.

Deputy Minister of Education Mykhailo Vynnytskyi, who participated in the Committee meeting, predictably emphasized that the anti-social draft law No. 10399 was supported by the Federation of Employers of Ukraine. There is no doubt that the privileged minority represented by the Federation will benefit from the innovations. After all, they will make it possible to forcibly hire qualified personnel immediately after graduation and turn those who will not be able to get an education due to its further commercialization into cheap labor.

***

Judging by the rhetoric of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, government officials wanted to get the draft through the Parliament as quickly as possible so that the new state funding system could start working in September 2024. As this article was being written, the draft law was adopted by the Verkhovna Rada in the first reading as a basis.

Justifying its decisions by the conditions of a full-scale Russian invasion, the goal of European integration, and the need to pay back the loans from the World Bank, the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine is deliberately attacking affordable education, while not introducing any significant change to improve the quality of education. Of course, reforms are needed, but they should be aimed at improving quality, expanding access to education, and providing real autonomy for universities under democratic governance instead of the dictates of feudal rectors.

However, the government chooses to make changes that boil down to outright saving on funding for students and universities. Instead of limiting the growth of tuition fees so that grants cover a significant part of these costs, future grant recipients are encouraged to find employment or take out loans. Instead of promoting the reintegration of children from the occupied territories into the Ukrainian educational space, they plan to save money on their education rights. Instead of job guarantees, government-subsidized students are offered coercion. All of this led to the launch of the #GrantNeGarant (GrantNotGuarantee) campaign by Priama Diia (the Direct Action) independent student union, in which students seek to draw attention to the problem and call for solidarity in the fight for a better future for Ukrainian universities.

Footnotes

- ^ Decision No. 5-rp/2004 of March 4, 2004.