Anton Yaremchuk is a cinematographer. In 2022, he co-founded the volunteer platform Base UA, an initiative to counter Russian aggression by providing humanitarian aid and support to civilians. Currently, the initiative operates in the Donetsk region. It covers a wide range of work, from a mobile clinic in a truck to evacuating the local population to rehabilitation art camps for children.

On October 7, 2023, Anton, having the necessary knowledge and skills, decided to join a humanitarian mission to Palestine. We talked to him about his participation in this humanitarian mission, his experience communicating with the locals, and his interaction with the Israeli military.

Maria Sokolova: Please tell us a little about yourself. Were you involved in activism and political life before the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine?

Anton Yaremchuk: I have lived in Germany for the last 12 years, but I am constantly involved in projects in Ukraine, so we can say that since 2017 I have been living in two cities. I work in cinema as a director of photography. I’ve always tried to be actively involved in what was happening in Ukraine, particularly through my profession. Since the Maidan, I have worked in various ways on projects that explored the war itself or the aftermath of the Maidan – I was purposefully looking for such projects.

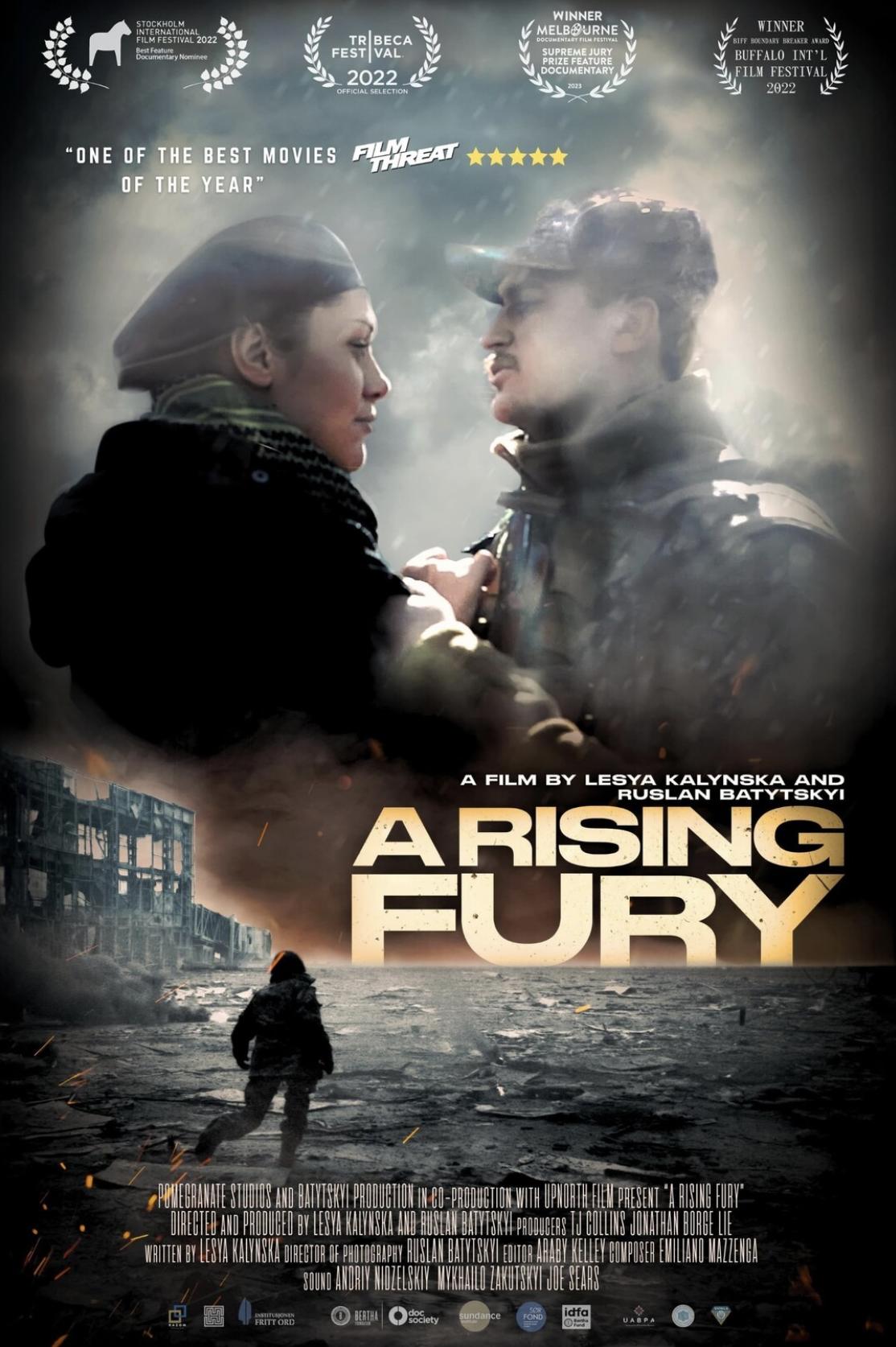

We made several feature films. One of them, Beyond Revolution, is about activists and journalists who entered the parliament after the Maidan: Nayem, Zalishchuk, and Leshchenko. We were interested in what happens to people when they find themselves in the system, how they change, and how much the system can be transformed. We also worked for many years on the Open Wounds project about the Maidan cases and the trial of the few Berkut officers who were in custody and who were eventually exchanged. A Rising Fury is the last project that took the longest to complete, as the final filming sessions took place after the full-scale invasion began. It is a detailed study of the processes of the last ten years, shown through the fates of several people, including the protagonist, who took part in the Maidan and the war, where he is still fighting.

Movie poster for A Rising Fury

What were you doing when the full-scale invasion broke out, and how did your volunteer work begin?

Just a month before the invasion, I was in Ukraine, where I started working on a long-term project with my team. This is a study of the connection of times: the problem of Ukraine, which is now in a space in which it is trying to distance itself as much as possible from the twentieth century as if it were not its own past. But this past is the only one we have, and until we process it, we will not be able to move forward. After the full-scale invasion began, I realized I would continue this film in the context of the war itself because these are also inseparable processes.

So, after February 24, 2022, I came from Berlin to Ukraine and immediately started filming in Lviv: large-scale flows of people, crowded train stations, and so on. I was there for the first six weeks. We drove people to the border and arranged for someone to pick them up on the other side. In the first year, for most of those involved in any processes, everything happened spontaneously: no one planned anything – you were just constantly on the go.

In the summer of 2022, we quickly found ourselves in the East. Given my previous film projects, I had training and war zone experience. At first, we worked in rounds lasting several weeks and began to evacuate civilians from hot spots. There was a great need for this, particularly in Siverskodonetsk. So, we started working there and have continued to carry out humanitarian activities since then.

In the summer of 2022, we registered an NGO when we realized that the war would last long and that people who could organize themselves were ready to devote a lot of time to it. It was a logical decision that made it much easier to interact with all the agencies.

At first, we worked in the Luhansk region, but after its occupation, we started working in the Donetsk region. We now have a wide range of activities, from a mobile clinic in a truck to rehabilitation art camps for children in the Carpathians. We have a cultural center in Kramatorsk and repair windows and roofs in the de-occupied territories. In this context, I managed to make only one feature film, which was launched and developed for a long time, right when the invasion began. So, I’ve been doing nothing else for these two and a half years. Most of the time, I was in Kramatorsk, except for participating in a humanitarian mission to Palestine, which lasted a month.

How did you decide to go there, and what exactly did you do there?

I have been following the situation in this region for a long time. I have read, watched a lot, and tried communicating with people. This isn’t some new conflict or a new situation that I learned about only on October 7, 2023. However, before I went to Palestine, I had never spoken out publicly about it because I felt that I could not say anything that had not already been said.

I saw what was happening in Palestine and wanted to get involved and help. After October 7, a coalition of several organizations was quickly formed, including Civil Fleet, where a close friend of mine works, and the medical organization CADUS, with which we actively cooperate in Ukraine. So, I knew people in these humanitarian missions. At some point, there was a need for people with my experience, so I joined.

The aftermath of the bombing of Khan Yunis in the southern Gaza Strip, May 7, 2024. Photo: Majdi Fathi / NurPhoto

Did you feel that you were more needed there than, say, in Kramatorsk? Did you have any doubts?

There were doubts, but not so much internal as technical. We have a very small team, and I am responsible for many processes as a project coordinator. So, my decision, among other things, meant that someone in the team would have to do more work. So, it wasn’t just a case of “go if you want, don’t go if you don't want.” However, the team and I decided that my trip to Palestine was necessary.

Even before the trip, I realized – and now, after this experience, I can confirm – that the level of the humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza is such that I have not seen in Ukraine, even in the first days. I don’t mean to say that these things should be compared. But, at the same time, they cannot be compared – it’s a completely different level. That’s why I have never questioned the need to get involved and help.

What were your expectations before the trip? Did they come true?

It was much worse than I expected. I was incredibly frustrated because the situation there was very difficult, and at the same time, there were many obstacles to work, especially in contrast to Ukraine, where we have had almost no restrictions for a long time – especially in the Donetsk region – and where almost anyone can get involved in any territory and work there. Palestine is the total opposite.

It was super hard for me: you are very much cut off from that environment and the people you are helping. First, because of all the mechanisms that Israel has built, and secondly, because international organizations, given the need to balance in the political plane, act following a more standard approach. There are many aspects of the organization of work that I strongly disagree with, and every time, I had a feeling that as soon as there was a formal reason to close our mission, it would be done. That’s why these international organizations are so cautious. This is understandable, but it makes work extremely difficult. For example, we had no possibility for free movement: we were either at the base or at an agreed destination. I couldn’t just go out and go to the market and communicate with people; I couldn’t personally find out what they needed.

That's how most organizations work, so emergency response and operational work become very difficult. You are always late with help, constantly relying on formal research and assessment. You seem to be there but are not “on the ground.” There are too many restrictions, both security and organizational and bureaucratic, that Israel has explicitly built to control and limit such activities.

It was already the final phase of a calmer situation when I was there, so we were working in a more routine mode. I worked as a medical evacuation coordinator, and for the first two weeks, we worked in a UN convoy. Our base was in Rafah, in Al-Mawasi, and we traveled north to Gaza City. We brought some resources there and evacuated the wounded. Most of them were children with injuries. Only a few cases were not directly related to the fighting. We evacuated the victims from the north to the south because the field hospitals and physical hospitals that still existed at that time had better opportunities to provide medical care. In general, everything worked within a very limited but well-established system for evacuating the wounded, mostly children, to Egypt.

In Gaza, the entire medical system operates exclusively in a state of total emergency. There are no conditions for long-term or rehabilitation measures. Everything’s done so that a person doesn’t die right away: some interventions, including surgery, are possible to increase their chances of full rehabilitation. Later, when Israel occupied Rafah, all this stopped. First, because people could no longer evacuate to Egypt, even those that we evacuated at the very end of our mission remained in the south for a long time, cut off, with no prospect of leaving and no way to return to the north.

Patients and internally displaced persons at Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, November 10, 2023. Photo: Khader Al Zanoun / AFP

What happens to people injured in Gaza after the occupation of the south?

When I was still there, there were quite a few hospitals, stabilization centers, and dressing stations that dealt with fresh wounds. For instance, there is the International Medical Corps Field Hospital, where about 150 people work in the emergency department daily. There is also the Palestinian Red Crescent. This organization has ambulances and is directly involved in transporting and evacuating the wounded to such hospitals.

When I visited, the situation was very difficult but still more or less under control. However, it has deteriorated dramatically with the resumption of the Israeli army’s offensive in the south. The medical system is currently in a catastrophic state. 200 wounded can be brought to the hospital at the same time. I would emphasize that no hospital can cope with so many injuries of this magnitude – this is physically impossible. You will never have enough resources.

The medical system continues to hold on thanks to the efforts of local medical workers, hundreds of whom were killed in defiance of international humanitarian rules. When I was there, about 60 international organizations were working in Palestine, of which about a third specialized in medical aid. Most of these organizations focus on working in specific locations or hospitals. They send 10–12 people, half of whom are surgeons and half are other specialists. They work there for 2–4 weeks. This is vital help, but given the scale of the crisis, it is the absolute minimum.

There are few physical hospitals left. One of the key ones is Shuhada al-Aqsa Hospital, the largest and most important in the region. However, facilities like al-Aqsa are under serious threat of closure.

Does the need for medical care remain constant?

The need may even be increasing because there are so many chronic diseases. In normal life, this would be part of the medical routine, but over time, these diseases become catastrophic when there is no access to medicines and certain procedures. In addition, there are confirmed cases of polio and other infections that pose an epidemic threat. The situation isn’t improving; it is only getting worse. So, the need for medical care doesn’t disappear; it can only increase or remain more or less constant.

The medical infrastructure has been almost completely destroyed, and the UN and international organizations have their hands tied to bring in the necessary medicines and instruments. That is, access to medical resources, without which work is impossible, even in safe areas, is severely limited.

The supply of medicines is limited to a minimum, and it is often unclear what this depends on. The thing is that Israel has created a super-bureaucratic system. Most of our movements in Gaza had to be approved 24 hours in advance. After the first approval, we had to wait for the “green light” just before leaving. In addition, there are checkpoints where you have to wait for additional approval. In addition to the complicated procedure for approving the route, the Israeli administration could also make changes to it.

How do the Israeli authorities justify this system of restrictions?

Nominally, this whole coordination system exists to protect you from Israeli fire. However, the experience of more than 300 days shows that this bureaucracy doesn’t improve your safety. If Israel decides to attack, no amount of coordination will save you.

They also say that the coordination system exists to make it easier to pass checkpoints. But even after all the approvals, you have to wait for hours. For example, the UN didn’t refuse Palestinian drivers on principle. Most of the time, this didn’t cause problems, but there were cases when the Israeli mobilized forces took off the route a trusted driver with whom we had traveled many times, undressed him, and told us: “You have 10 minutes, either go back or forward!” And we couldn’t do anything about it.

Notably, every time we crossed a checkpoint, weapons were pointed at high-ranking UN officials, who are protected by international law and all possible UN charters. And this is just one example – there are many such situations. Israel does whatever it wants; there is no leverage to influence their actions. Of course, this will have consequences in the long run, but for now, Israel is acting without any restrictions. And I understand that even the United States, I’m sure, has made significant efforts to bring about a ceasefire. But no one can do anything.

A protest against the entry of humanitarian aid trucks into the Gaza Strip at the Nitzana border crossing in southern Israel, February 14, 2024. Photo: Erik Marmor / Flash90

For me, this is a global catastrophe because it reveals that we live in a world of double standards. Israel can do what it is doing in Gaza, but for some reason, the UN, the US, and others say Russia has no right to do the same in Ukraine. What is happening in Palestine, especially in the context of civilian casualties, is unimaginable. It’s simply unthinkable.

This war of Israel cannot be won by military means. The Gaza Strip is a huge, urbanized area, densely built and inhabited by tent cities. Almost 99% of its population is civilian. Only thousands or tens of thousands of people from paramilitary groups are scattered in this space. How can this war be won? Only through total destruction and eviction of people from this territory.

How do the Palestinians you spoke to see the situation developing?

This is the first time since 2006 that most people want to leave. On the one hand, yes, they are very attached to the land and realize that they will never be able to return if they leave. This is exactly what Israel wants. Even if the war ends tomorrow, it’s no exaggeration to say that everything in Gaza is destroyed. All of Gaza looks like Bakhmut or Mariupol. All the infrastructure, all the buildings, all the institutions, social systems – everything is destroyed. And no one will rebuild it, especially for the local population. People realize that any prospects for the future have been physically destroyed.

According to my unrepresentative statistics, based on conversations with a small group of people, the majority hate Hamas. In fact, in 2006, there was a civil war or, rather, a war between the elites. And Hamas either crushed or physically destroyed its opponents. So, it is, first and foremost, a dictatorship, and secondly, a paramilitary dictatorship and a radical Islamist dictatorship.

Any positions, from school principal to hospital director, or any high-ranking people in general, were either Hamas members or those who pragmatically had to be in the party or close to it. At the same time, a significant part of the population didn’t agree with this situation. But any attempts to demonstrate or oppose Hamas, for example, were usually quickly and brutally suppressed through repression. So, I think that for the Ukrainian audience, one of the most false and dangerous narratives is the statement that everyone in Gaza is rooting for Hamas.

This is not true. The civilian population of Gaza suffers both from Hamas and from Israeli actions. Unfortunately, Hamas has monopolized power and has been strengthening its positions, including its military, for almost 20 years, including with Israeli assistance. And in the end, what happened happened.

We now see that after the assassination of Ismail Haniyeh, the most radical, militarized cell of Hamas finally came to power. And this will certainly not help de-escalate the situation. This is exactly what Israel was hoping for. The same Israel that since 2006 has done a lot to make Hamas what it is, for instance, by providing resources or allowing their supply. Israel did this because it is much more convenient to have such an enemy, as it can justify its cruelty in the name of justice.

Ismail Haniyeh’s son in the Gaza Strip on the ruins of the Hamas leader’s house destroyed by an Israeli air strike, October 29, 2024. Photo: Majdi Fathi / NurPhoto

And how did the civilian population react to the attack in October?

Now, they are all very dissatisfied and, at the same time, largely blame Israel for what is happening. At the same time, they believe that Hamas also bears part of the responsibility because they are convinced that it was its actions that led to this situation.

They have always started by categorically condemning and not supporting any actions aimed at killing or harming civilians, emphasizing that this is categorically haram and unacceptable in Islam. Some are more positive about the armed opposition, viewing it as an attempt to liberate and confront Israel in the classic sense of an oppressed nation’s struggle for independence from occupation.

And when you talked about your experience with other people in Ukraine, did you hear from them any myths about Palestine?

Not in my bubble. Judging by the media’s reaction to the October 7 attack, I’m sure there are a lot of myths. But after the world media began to cover Israel’s war crimes, it became more difficult to maintain uncritical support for Israel. Since then, the news coverage of Israel and Palestine in the Ukrainian media has significantly decreased. However, in my opinion, this was all misinterpreted from the beginning, and later most people lacked additional reflection. When I tell people in Ukraine about Palestine, many ask: “Where can I read about it?” If you don’t intentionally look for this information, you won’t know anything about it.

Have you had an impression that Ukrainians associate themselves more with Israel? That Israel is strong and powerful, and Ukraine is the same way. Even though it seems more parallels can be drawn between Ukraine and Palestine. Do you think that these parallels should be drawn at all? And can such parallels contribute to international solidarity between the oppressed and victims of imperialism, such as Ukrainians and Palestinians?

This is counterproductive and wrong because parallels can only be drawn in private conversations between people with certain knowledge and critical thinking. It seems to me that this should not be done at the level of the mass media.

Israel and Ukraine aren’t similar in any way. This should be understood not only nominally but also conceptually: the Israeli project was Zionist and colonial from the very beginning, even without negative connotations. This is stated in their manifestos, and they were fully aware that they were going to colonize certain territories with certain local populations. So, it is clear to me that this is the opposite of Ukraine, which is defending itself against Russia, a colonial or imperial power.

Israel is a very modern, complex, and, in some ways, cunning military machine that operates on many levels. This experience may be relevant for Ukraine, although in a completely different context and with different initial data. We are still searching for our identity and building an understanding of who we are and what Ukraine is. In Israel’s case, it’s the opposite: they had a clear idea of their goal, a clear project for the country, and implemented it very quickly. Perhaps we could learn from them – how to purposefully and effectively build institutions, a political system, and an economy. But we have a different starting point, and I hope Ukraine will do it in a different way. In the long run, I would like to see Ukraine stand up for the weak and act ethically, perhaps not always pragmatically, but ethically. Maybe this would also help the country build a name for itself. For example, when we provided airplanes to small Macedonia during the Yugoslav conflict while everyone else turned their backs. I think supporting the weak is about a long-term commitment. Declarative support of, say, Israel doesn’t give us anything substantial. Instead, Ukraine should focus on building a more neutral and balanced dialogue with the countries of the Global South. This will be much more effective for us, and I hope it will happen.

Talked to Anton: Maria Sokolova

Translation from Ukrainian: Pavlo Shopin

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva