Should the Left support the division of the world into imperialist spheres of influence? A year ago, the very posing of such a question would have surprised me, since the answer seems obvious: of course not. Unfortunately, the apparent sympathy with Russian aggression against Ukraine by many on the Western left has shown that this is not so obvious.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, Susan Watkins actually endorsed Putin’s desire to divide Europe into spheres of influence between Russia and the United States in a New Left Review editorial. Shortly after my response to Watkins, the spheres of influence policy was supported by Branko Marcetic in an article for Current Affairs. In it, he compared the U.S. response to the Rusian invasion of Ukraine to the Eisenhower administration’s caution in responding to the Soviet Union’s suppression of the 1956 revolution in Hungary. Marcetic complained, “Washington and allies’ sensitivity during the conflict to the delicate European balance of power, and their concern around the optics of appearing to overtly meddle in an adversary’s sphere of influence, is today cast as reactionary.”

Perhaps living in wealthy imperialist states, it is not easy to understand why the division into spheres of influence is a bad thing. However, even if he himself did not realize it, Marcetic raised an important question: the connection between the Soviet policy of spheres of influence in Europe and the rightward turn in post-socialist societies, culminating in the Russian aggression against Ukraine.

Two Status Quos

It is not the purpose of this text to discuss the many shortcomings of Marcetic’s article. But before turning to the main topic, it is worth pointing out some of its flaws. Its author ignores the main difference between the conflicts he compares: while Hungary was indeed in the Soviet sphere of influence, post-Soviet Ukraine is not and never was in the Russian sphere of influence. Of course, the Kremlin believes that Ukraine should be a controlled fiefdom, but in reality, even the most pro-Russian of Ukrainian presidents, Viktor Yanukovych, sometimes clashed with Russia and negotiated the Association Agreement with the EU.

The Cold War ended with agreements that reversed the previous division of Europe into spheres of influence. Some readers may argue that there was an informal promise not to expand NATO eastward. But this was not an agreement regarding spheres of influence. Moreover, this promise was not about military cooperation between Eastern European states and the U.S. Ukraine, too, has been developing military cooperation with the U.S. almost since independence, as did Russia between 1991 and 2008. After all, the promise not to expand NATO was made to the leadership not of Russia, but of a long-defunct state, the Soviet Union, which included not only present-day Russia, but also Ukraine.

This reveals one important, but not obvious, similarity between the approaches of Eisenhower and Biden: neither of them dared to violate the status quo. But if in one case it meant reckoning with the Soviet Union, in the other case it meant the opposite: giving up spheres of influence. When in December 2021 the Russian Foreign Ministry published draft treaties with the U.S. and NATO, the U.S. responded by putting forward counterproposals on arms control that met Russian security interests; but on the main Russian demand for a division into spheres of influence in Europe, they refused.

This shows how off-base Marcetic’s comparison is. Each case is unique, and for a productive comparison, we need to analyze both the similarities and the differences. At the same time, we can disregard many differences that are not important for the problem we are analyzing. But the fact that Ukraine did not – and does not – belong to the Russian sphere of influence is a central distinction that cannot be overlooked. It has a direct impact on the behavior of governments and the developments that follow.

Marcetic ignores how cautious the Biden administration’s approach was and remains. Like Eisenhower, even before the Russian invasion, Biden rejected the idea of sending U.S. troops to Ukraine and constantly reiterated that the U.S. would not go to war with Russia. The difference in policy between Biden and Eisenhower, however, is largely due to the different circumstances and behavior of the Hungarian and Ukrainian governments. While Imre Nagy rejected Western military intervention and called on the UN to recognize Hungary’s neutrality, Volodymyr Zelensky rejected the idea of Ukrainian neutrality before the invasion. After the full-scale war started, Zelensky not only demanded new weapons on a regular basis but also called on NATO to close the skies over Ukraine.

So in the case of present-day Ukraine, the correct question is this: Did the U.S. do the right thing in rejecting the proposal to divide Europe into spheres of influence? The answer to this question must take into account not only the direct consequences of the war, but also the longer term consequences of such arrangements. And to do so, it is not unreasonable to consider the consequences of the last division into spheres of influence in Europe after World War II.

The Hungarian Comparison

The peculiarity of the Western countries’ reaction to the Hungarian Revolution in 1956 was that they not only refused military assistance, but that they were also afraid to give the revolutionaries substantial political support. Might the Hungarian Revolution have been saved in this way? Perhaps we will know the answer to this question when the Russian archives are declassified. Nevertheless, much more confidently we can answer other crucial questions. Would the policy of the USSR toward its Eastern European satellites have been more cautious if the international community had reacted more harshly to the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution? Would it have been able to save the Prague Spring? The answers to these questions are far more likely to be in the affirmative than to the first one.

Armed local residents of the city opposed the invasion of Soviet troops into Hungary, Budapest, November 5, 1956 / Photo: AFP

The victory or suppression of a revolution affects more than just the countries in which it took place. The Cuban Revolution spurred revolutionary movements in Latin America and around the world. Had the U.S. suppressed it, the “turbulent sixties” might have looked very different. Perhaps this did not happen due to the fact that the USSR did not recognize Latin America as a sphere of influence of the United States. Unlike Eisenhower, Khrushchev defended the Cuban revolution and put the world at risk of nuclear war, but he may have saved the Cuban revolution. Had the Hungarian Revolution not been suppressed, the sixties might have been much more turbulent in Eastern Europe. Unfortunately, this did not happen, and after the suppression of the Prague Spring, a gradual turn to the right (reinforced by the neoliberal turn in the capitalist world) began in the so-called “Second World.” Dissident circles in the USSR and its satellites increasingly shifted from socialist positions to liberal and conservative ones, and nationalist sentiments grew stronger in these societies. Henry Kissinger’s strategy to strengthen the sovereignty of Eastern European communist states during détente, which he promoted in the hope that this would lead to the Finlandization of these countries (though he was wrong), also contributed to the conservative turn to some extent.

The result of suppressing uprisings in Eastern Europe was that when the need to renew “real socialism” became apparent even to the Central Committee of the CPSU, it was already too late. The new revolutions provoked by perestroika no longer led to “socialism with a human face” but to neoliberalism. Subsequent Western-initiated “shock therapy,” in turn, entailed even more reactionary tendencies in post-socialist societies. The apex of this process was the transformation of the Putin regime, which not only turned to aggressive territorial expansion, but, in the words of Volodymyr Artyukh, began to form an anti-revolutionary “Holy Alliance” – much like tsarist Russia did in the 19th century.

The division of the world into spheres of influence sought by the Kremlin consolidates the domination of the great powers. It also undermines the ability of revolutionary movements and small countries to exploit the contradictions between them. In many ways, it is this policy that has made democratization and renewal of “real socialism” impossible, with the result that neoliberalism, conservatism, and nationalism have come to dominate post-socialist space.

The toppled monument to Joseph Stalin in Budapest, October 1956

The UN and Spheres of Influence

The division of Europe into spheres of influence after World War II had negative consequences – and not only for those countries that found themselves in the Soviet sphere. On the other side of the Iron Curtain, the main victim was Greece, where Anglo-American troops, together with former collaborators, began to exterminate pro-Communist, partisan anti-fascists. Moreover, the USSR not only agreed to allow Greece to fall under the British sphere of influence but also actively used this agreement to strengthen its dominance in Eastern Europe. As historian Geoffrey Roberts has written, “Stalin and Molotov never tired of deflecting Anglo-American complaints about the exclusion of Western influence from Eastern Europe by pointing to Soviet forbearance in relation to Greece.”

But was there a better alternative to a policy of spheres of influence after World War II? The most paradoxical thing about the history of the postwar international order’s formation is that it was the representatives of the USSR who insisted most on the division of spheres of influence. This was the case despite the fact that the very emergence of the USSR was closely linked to hopes for a world revolution, and its leaders proclaimed themselves followers of Lenin, who was sharply critical of all aspects of covert diplomacy, including the very idea of spheres of influence. Moreover, for the USSR, attempts to divide Europe into spheres of influence with Britain and the United States were a logical continuation of the preliminary agreements with the Third Reich that both Moscow and the Western democracies had before the war.

Unlike Stalin, the Roosevelt administration opposed spheres of influence. This was largely thanks to some State Department officials, such as Leo Pasvolsky, who promoted a universalist vision of the UN as a centralized international organization, one that would do away with spheres of influence. Moreover, as Peter Gowan notes, “Pasvolsky—after committing the faux pas of reminding his boss that the Japanese had described their Co-Prosperity Sphere as a Monroe Doctrine for Asia—went so far as to observe that ‘if we ask for the privilege, everybody else will,’ which would ‘push the Soviets into a combine’ of their own, a prospect to be thwarted. Roosevelt was sympathetic to such considerations.”

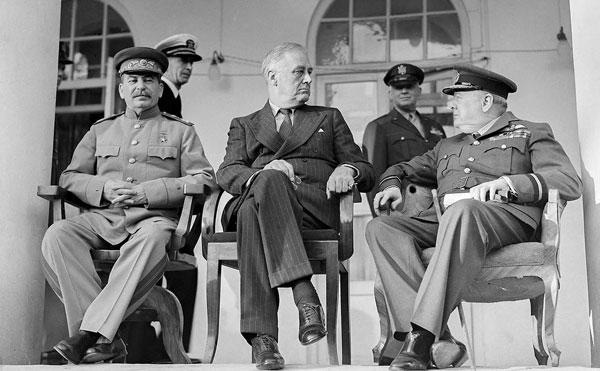

Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill at the Tehran Conference, 1943 Photo: Interfoto / PHOTAS / TACC

After Roosevelt’s death and the defeat of Germany, U.S. policy on this issue changed. But it is possible that Roosevelt’s position on spheres of influence saved one country from Soviet occupation: Finland. Milovan Djilas wrote in his memoirs that Stalin called it a mistake not to occupy Finland because “we looked back too much on the Americans, and they would not have lifted a finger.”1

Roosevelt’s (or rather, Pasvolsky’s) project failed, and instead the confrontation between the former allies intensified, and the Cold War began. But it is worth paying attention to who on the American side was most culpable. First, there was the reactionary sector of the State Department, dealing with Latin American affairs under Nelson Rockefeller. He tried to maintain U.S. hegemony in Latin America and to this end pushed through changes to the UN Charter. As Peter Gowan has pointed out, John Foster Dulles later told Rockerfeller, “If you fellows hadn’t done it, we might never have had NATO.”

Author: Taras Bilous

First published on Spectre Journal

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva