This essay will explain why it is that despite historically unprecedented globalization of free trade, the rich countries remain rich, while the poor countries remain poor. Beginning here, and more closely in future article,we will use a theoretical perspective derived from the work of the Marxist economist Arghiri Emmanuel to analyze the history and present tendencies of capitalist Ukraine’s economic development.

David Ricardo’s theory of economic specialization by comparative costs

Bertil Ohlin’s theory of economic specialization by factor endowments

The lasting global inequality in wages

The reproduction of unequal exchange

2: The effects of wages on economic development

The necessity of the division of the world into low- and high-wage nations

David Ricardo’s theory of mutual prosperity through free trade

The IMF and WB in their report on Ukraine often speak of ‘comparative advantage’[1]. They say that since Ukraine’s ‘comparative advantage’ lies in agriculture and some labor-intensive manufactures, Ukraine should specialize in them and deindustrialize. Let’s examine the logic of this theory of specialization by comparative cost advantage. It was given its most famous formulation in the work of the early 19thcentury British economist, David Ricardo, which in many ways distilled Adam Smith’s work on the subject.

David Ricardo

Ricardo’s argument[2]

So there is clearly an ideological element to Ricardo’s argument. Some economists[3] have noted that his analysis of foreign trade abandons his realistic analysis of capitalist competition inside a nation, in which the strong – those with higher labor productivity and lower unit costs – beat the weak, and selling price is determined by production cost. In foreign trade, both countries can only gain from free trade. Free trade is said to be a game where all competitors can, at worst, gain less than others – there are no losers.

This is because Ricardo assumes that in foreign trade (unlike in domestic trade), the quantity of money in a nation determines price, alongside cost of production. The more productive nation would supposedly be forced to sell its commodities at a higher price due to inflation resulting from the increased money its foreign trade gave it. These higher prices for the more productive nation would give the advantage to the less productive nation. In this way, each nation could specialize in its own commodity. The weaker nation specializes in the commodity in which it has the ‘comparative advantage’ in – the one it has the comparatively smallest productivity gap qua the stronger nation.

Source: AP Photo/Guillermo Arias

This is how one of the foundational statements of the liberal theory of trade proposed that trade deficits and surpluses were momentary phenomena, that free trade tends towards the mutual prosperity of all involved. It also implies that state intervention should be limited to currency devaluations – international trade, according to this conception, is kind to nations with lower productivity, and hence there is no need for the state to modernize production.

In reality, our world has always been one of

Source: Reuters/Antony Njuguna

But there is also an aspect to Ricardo’s argument that conforms perfectly well to capitalist logic. Capitalists seek to spend as little money as possible, in return for the largest gain of money possible. Why make expensive investments in a sector where you will still probably be beaten by foreign competitors? Better to play it safe, and specialize in what your nation has already given you. Why invest in the dying automobile sector, people can just import cheaper cars produced in a high-productivity nation like Germany? Why worry about industry, when your own country has soil which can grow lucrative cash crops for minimal investments? The fact that this specialization may render much of your country’s population unemployed is irrelevant. Capitalists are individual producers, seeking to remain cost-competitive in whatever sectors possible – societal concerns are not part of the game.

Bertil Ohlin’s theory of economic specialization by factor endowments

Ricardo’s theory of international trade was given its contemporary update by the 20thcentury economist Bertil Ohlin’s[6] theory of specialization by factor endowment. In short, it argues that economic specialization stems from how much of an economic factor (such as labour, capital, or land) a nation is ‘endowed’ with. If a nation has a lot of labour relative to capital (‘labor-endowed’), labour will supposedly be cheaper, which means a nation will (and should) specialize in labor-intensive products (commodities whose production requires relatively more labour), while ‘capital-endowed’ nations should specialize in capital-intensive products (commodities whose production requires relatively more means of production).

Logically, Ohlin’s theory is the same as Ricardo’s – what use is there investing in sectors you are not immediately competitive in, if more can be globally produced if everyone specializes in what they are already most cost competitive?

Source: Reuters/Siphiwe Sibeko

Ideologically, Ohlin’s justification for free trade revolves around incomes. Since all prices are assumed to be determined by the ‘inter-dependence of supply and demand’, the price of a productive factor is equal to its scarcity or abundance relative to the demand for it. International inequality in the remuneration of labor is hence made into a result of not enough free trade. Incomes must be low in a country because there is not enough capital (demand for labour) relative to the supply of labour.

The lasting global inequality in the rewards of labor

But this idea that free trade leads to the equalization of incomes is even less realistic than the idea that it leads to neutral trade balances. We continue living in a world of tiny islands of parasitic wealth amidst a sea of poverty.

Free trade has never spread over so much of the world so quickly as it did in the 19980 and 1990s, yet the income gap between the fifth of the world’s people living in the richest countries and the fifth in the poorest was increased from 30:1 in 1960, to 60-1 in 1990, to 74-1 in 1997[8]. The absolute gap between the mean per capita incomes of high- and low-income countries increased from $27,600 in 1990 to over $42,800 in 2018. The constantly repeated claim that ‘free trade has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty’ is only true regarding China, hardly the most pro-market country itself, and one where ‘exiting poverty’ is defined as earning more than 1.90 2011 PPP dollars a day. If we exclude China, the free trade era has seen increased poverty for the majority of the world[9]. In capitalism’s centuries-long existence, there have always existed enormous wage gaps between nations. Those which had higher wages yesterday are those which have higher wages today[10]. There have been three examples of sizable low-wage nations which became high-wage through capitalist means – Japan, South Korea, and possibly Poland[11].

The average world national income per capita (in current US$) was $9290 in 2018. Of the 183 nations for which data is available, 98 had a per capita income below $5000, 30 had a per capita income between $5000 and $10,000, 20 had a per capita income between $10,000 and $20,000, and 44 had a per capita income above $20,000.

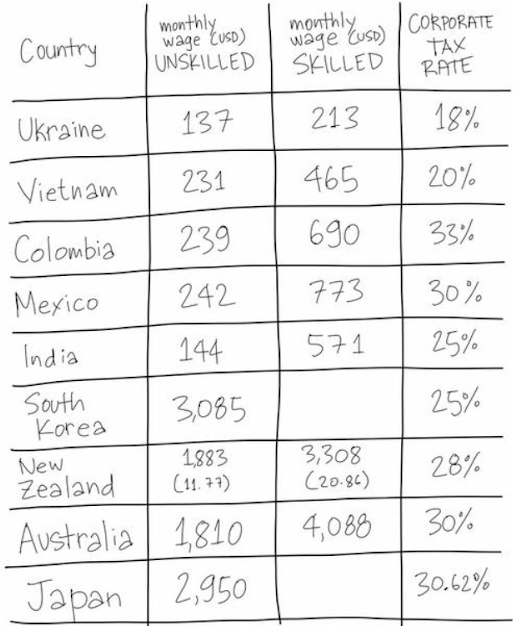

Here is some recent data on wages:

LO data shows[12] that there has been barely any change in relative international incomes between the period 1995-2009 and 2000-2014. Wages rose in China and Mexico, while still remaining very low, while those in Indonesia fell.

Here is a diagram drawn by Marko

Ethiopia, regarding which there is no shortage of articles praising it as the ‘economic miracle of Africa’, a nation into which capital has been flooding in recent years in search of its

Ohlin or other bourgeois economists would simply reply that Ethiopia hasn’t participated in free trade enough, that they should exploit their factor endowment of cheap labour more. But real capitalists do not seem to share their idea that wages in Ethiopia should rise through trade. Increased Ethiopian worker militancy in demanding a higher wage is unacceptable for foreign capital – “We didn’t bargain for this,” an executive at one supplier told an investigator. $26 a month is close to an upper limit. “There is only so much brands will tolerate before they take their business elsewhere.”

US manufacturing wages are currently 8 times higher than those in Mexico, despite the fact that both nations have been highly economically integrated since the 1994 NAFTA free trade agreement. After years of free trade integration with the European Union, average Ukrainian labour costs in 2018 remained 15 times lower than in Germany. After 3 decades of export-oriented development, Bangladeshi textile wages in 2018 were still at $64 a month, or 31 cents an hour (and this is after a 77% wage increase following a factory disaster which killed 1134 worker in 2013).

China, which has used free trade relatively to the advantage of its bourgeois through extensive state economic intervention, still has manufacturing wages 5 times lower than the USA, and tens of millions in the more inland regions work on a much lower wage.

Free trade has not led to the equalization of incomes. The world of free trade is one of massive wage differentials. These wage differentials are just as likely to increase in size as they are to decrease.

1: Unequal exchange

Why is it that free trade does not lead to the gain of all involved?

Unequal exchange takes place in international economic relations because capitalism is an economic system which reproduces itself using money, and in which economic agents (individual capitals) are motivated by maximizing their money profit. The theory of unequal exchange, created by Greek Marxist economist Arghiri Emmanuel[14], extends this elementary fact about the capitalist mode of production to the scale of the global economy.

Due to its profit-seeking nature, capital invests more in sectors with a higher rate of profit (ROP). The acceleration of supply in these high-profit sectors exceeds demand to the extent that prices in these sectors fall, thus reducing the ROP in these sectors. The opposite process takes place in low ROP sectors. Because it is characterized by free competition, the capitalist economy tends towards the equalization of the ROP throughout all sectors[15].

Source: Guang Niu/Getty Images

The problem is that while capitalist competition certainly requires that all members of the bourgeois receive equal reward relative to their investments, there is not the same need for the global working class to receive an equal income. Capital is globally mobile and competitive, but labour is not – it is confined by borders, walls, by the anti-immigration politics that is so perennially popular in the rich nations. Unequal exchange arises due to the fact that the world economy is a collection of separate nations, in which the cost of wages (variable capital) is dramatically variable.

The price (p) towards which a commodity tends to be sold on the market is given by its cost of production (the sum of the costs of variable capital v, and constant capital c, or means of production) multiplied by a rate of profit (r) which has been equalized by the movement of the entire economy.

p = (c + v) × (1 + r)[16].

Since the cost of production in a low-wage nation is lower than that in a high-wage nation, the price of commodities produced there will be lower than the price of commodities produced with high-wage labour power. Note that the price of a commodity is more influenced by the price of the labour power used in its production if its production is labour-intensive – if there is a higher ratio of v to c.

The fact that there sometimes exist different average rates of profit between nations does not disprove the point. In 2000, there was a dramatic difference in average profit rates between China and the US, being above 30% in the former and below 15% in the latter[17]. But in this case, the ROP was only temporarily 2 times higher in one country, while the nominal price of labour power in low-wage nations is generally 10-10 times lower than that in high-wage nations. In the 2000s, Chinese labour power was generally 20 times cheaper than US labour power[18]. Emmanuel determines that for there not to be unequal exchange, there would have to be a differential in profit rates to the benefit of the low-wage nation at least as large as the wage differential[3].

Source: Kostyantyn Chernichkin / Kyiv Post

China’s rate of profit has fallen since its early 2000s heights, now being only 2% higher than that prevailing in the US. The tendency towards equalization of the rate of profit is stronger than countervailing tendencies for differentiation among national rates of profit, because the essence of capital is to invest where there are the highest profit rates.

Unequal exchange today

The phenomenal manifestation of unequal exchange has been aware to economists for almost a century now – it is the fact of the declining terms of trade between high-wage (core, or imperialist) and low-wage (peripheral) nations.

Note that the worsening terms of trade of the periphery/low wage nations show the extent to which wages (and hence, prices) in the imperialist nations grow faster than wages in the peripheral wages. They do not show the actual extent to which commodities produced using high-wage labour are overpriced, and commodities produced with low-wage labour underpriced[19].

However, those who first noted this phenomenon, the economists Raul Prebisch and Paul Singer, did not link it to wage differentials[20]. Instead, they supposed that it was due to some sort of ‘inferior demand-structure’ of ‘raw materials’ as opposed to ‘manufactured goods’. Unfortunately this view is still widespread today, even among Marxists. But while it is impossible to prove that certain groups of commodities enjoy ‘structurally weak demand’, it is an observable fact that low-wage nations are prone to trade deficits and worsening terms of trade.

The top exports of Mexico and the Philippines are computer chips, cars, and machinery, while those of New Zealand and Australia are all ‘raw materials’ – eggs, honey, coal, crude steel, meat. But average incomes in the latter two nations are between 15-25 times higher than those in the former two. 33% of Australia’s merchandise exports are ores and metals. The WB’s data on high-technology exports as % of manufactured exports displays absolutely no correlation with incomes. Hong Kong and the Philippines have the highest values, the Central African Republic ranks in the top 10, and there are only 2 high income nations in the top 15. The idea that ‘industrialization’ is the route to prosperity,

The era of neoliberal globalization (the spread of free trade regimes across the world) has often seen declining terms of trade for the low-wage nations. Contrary to the hopes of their national bourgeois, specializing in the manufactured goods of the high-wage nations did not mean that they could sell them at the high prices the high-wage nations did. The 1999 UNCTAD trade and development report notes how the terms of trade for developing nations as a whole fell by more than 5% per annum in the 1980s, and that the terms of trade for non-oil exporting developing nations declined by 1.5% per annum since the 1980s.

UNCTAD discovered that ‘the prices of manufactures exported by developing countries fell relative to those exported by the European Union by 2.2 per cent per annum from 1979 to 1994.’ For commodities solely or mainly produced by low-wage nations, the decline of the terms of trade in recent years has been enormous – UNCTAD reports how ‘between 1980 and 2003, the price of food . . . declined by 73.3 percent; agricultural raw materials prices fell by 60.7 percent; and the price of minerals, ores and metals declined by 59.5 percent. By the first half of 2003, the price of coffee had lost 83 percent of its 1980 value’[21].

Meanwhile, the worst drops in China’s terms of trade were precisely for those relatively technologically complex commodities hitherto traded by high-wage nations– this is most likely due to the fact that as China began specializing in these commodities, their price began dropping as the high-wage nations left these sectors and specialized in other sectors, while other low-wage nations also began specializing in these spheres. More recently, UNCTAD has calculated that between 1980-2014, the terms of trade[22] for the developing nations worsened by 0.6% annually, with that of Asia (which has participated most in free trade) worsening by 1.3% annually, while the terms of trade for the developed nations remained unchanged.

Source: People.vcg

A more exact analysis of the loss suffered by the low-wage nations by engaging in free trade due to unequal exchange is given by the relation between MVA (Manufacturing Value Added) and total exports. MVA measures how much new value (as measured by price) was created in the nation, ie, it excludes inputs that were bought from other nation[23]. The World Bank[24] has shown that, between 1990 and the early 2000s (the peak of free-trade globalization), MVA from 55 low-wage nations only increased by 46.3%, while total manufactured exports grew by 329%. Meanwhile, MVA in the 16 high-wage nations increased by 14.2%, while manufactured exports increased by 127.4%. If in 1990, the ratio of MVA to manufacturing exports in low and middle-income nations was 1.8, in 2002 it had fallen to 0.2, while the opposite trend occurred in the high-wage nations, with the ratio doubling from 1.0 to 2.0[25]. In Ukraine between 2008 and 2012, the value of exports increased by 63%, but that of MVA by only 35%.

What this means is that the price paid to the low-wage nations for its own production has been decreasing relative to the price of their imports from high-wage nations. When the exports of the low-wage nations increase, this does not necessarily mean there is more domestic value-added, it often just means that they import more overpriced products from high-wage nations a

The reproduction of unequal exchange

It is not viable for the low-wage nations to escape their miserable situation by simply specializing in the commodities of the high-wage nations. First of all, it is very difficult for the low-wage nations to do this (especially under conditions of free trade) because the high-wage nations dispose of much better productive techniques. This productive superiority is itself connected to the high wages in these nations, which we will analyze shortly. Means of production that give such high labor productivity are very expensive, and due to unequal exchange the low-wage nations have low funds at their disposal. Furthermore, it has taken many decades for the rich countries to perfect the techniques they use to dominate the markets they specialize in, and it is very difficult for poor nations to acquire the experience necessary to be competitive, not to mention the massive outlays on research and development necessary that only the rich countries, with their enormous tax base, can finance.

But if a low-wage nation acquires the technologies used by high-wage nations for their economic specializations, the low-wage nation will obviously liquidate the high-wage nations in competition. To prevent this, the high-wage nations will make a big noise about ‘social dumping’, which is the supposedly ‘unfair advantage’ enjoyed by the low-wage nations in using cheap labour and hence being able to undersell their competitors. Note that when it comes to practical matters, the imperialist bourgeois is entirely willing to acknowledge the existence of unequal exchange. Protectionist measures by the high-wage nations have been ‘liberally’ employed against low-wage nations first against Japan in the 20thcentury, and more recently, against China. A cursory look at any trade agreements between high and low-wage nations shows us that we live in a world of economic apartheid, in which low-wage nations are granted access to the vast markets of the high-wage nation at the price of being forbidden to trade a wide range of commodities currently specialized in by the rich nations[26]. This is well illustrated by the refusal of the EU to grant Ukraine ‘industrial bezviz’ for commodities that the European nations specialize in, even after years of trade integration.

Trading blocs between the high-wage nations like the EU, by keeping strict control over the largest consumer markets of the world, are generally sufficient to force the low-wage nations to specialize in what the high-wage nations allow them to import into their consumer markets. The high-wage nations can simply refuse to import whatever commodities they do not desire the low-wage nations to export. The low-wage nations have tiny markets in which few commodities can be sold, meaning that they are forced to do whatever necessary to gain access to the markets of the high-wage nations.

Source: Yoshikazu Tsuno © AFP

Where commercial means are inadequate, military ones may become necessary to keep the low-wage nations in their place. We can see this process inexorably

Besides non-economic solutions, the way the high-wage nations can deal with encroachment by the low-wage nations on their economic specializations is for the high-wage nations to simply specialize in something new, which is quite easy for them, given their enormous productive powers. The low-wage nations will then see their supposedly ‘expensive manufactured goods’ devalued as the only producers become low-wage nations.

2: The effects of wages on economic development

There are some quite obvious results of unequal exchange on the economic development of the low-wage nations. First of all, it means that they dispose of less money with which to modernize their production. Second, given that the high-wage nations dominate in the production of a wide range of important commodities, the low-wage nations often find themselves in a trade deficit with regards to these nations, or are forced to dramatically curtail internal consumption (both productive and unproductive) in order to be able to pay for it with its exports. Third, it makes it difficult to maintain any decent standard of living through imports without running into balance-of-payments problems. To temporarily fix these problems, the nations find themselves dependent on international creditors, which in turn push these countries to liberalize, to open themselves to free trade and to market mechanisms – which is precisely what reproduces their own economic weakness.

Most importantly, it is low wages themselves which keep these nations poor. There are four reasons why low wages ensure economic stagnation:

- Capital will avoid low-wage nations for lack of a market.

- High-wage nations attract labor-saving technologies and upskilling of labor, while the opposite is true for low-wage nations.

- High wages increase the tax base.

- Skilled laborers flee the low-wage nations for the high-wage nations.

Capital does not care about waiting to create new markets – it needs to sell its commodities now, or else it will be beaten by others who have already sold. The main problem of capitalism being to sell, capital tends to stay close to those areas with the highest purchasing-power.

Capital prefers high-wage nations because there are more investment outlets – there is more purchasing power. According to the world bank, of the world’s $22.96 trillion current USD of fixed capital, $12 trillion (52%) is located in the high income nations, which only account for 16% of the world’s population. For instance, between 2017 and 2019, of the $4735 billion in FDI (foreign direct investment) across the world, only $2225 billion of that went to nations outside of North America, Japan and Western Europe (‘the developed world’)[27].

While the developed world absorbed 46.9% of the world’s FDI, it makes up 13.8% of the world’s population[28]! This is also a false comparison, insofar as the rich nations have plenty of their own capital apart from FDI, in contrast to the poor nations, which depend on FDI for investments. And this, in a period called ‘free trade’, where it is constantly repeated that the poor nations have never been so ‘in demand’ by the capital of the rich nations.

Today, we find ourselves in a moment of international economic stagnation. World FDI inflows reached have remained stagnant or declining after 2007[29]. According to UNCTAD FDI inflows barely exceeded their pre-2007 peak in 2015, and then proceeded to decline by 40% between 2015-2019. According to the World Bank, net FDI inflows peaked in 2007 at $3.1 trillion USD, sharply declining after, with the 2015-16 ‘recovery’ only reaching $2.69 trillion USD, and a total collapse in 2018-19 – only $1.2 and $1.7 trillion USD.

Capital will not be flooding the poorest nations any time soon. The core nations are entering into a long-term economic crisis, eliminating the major demand for the products of the low-wage nations. According to the 2019 UNCTAD world investment report, there was 28% less FDI to the transition economies (the former Soviet bloc nations) from 2017-8. For the least developed countries, FDI inflows declined from $27.3 billion in 2014 to $21.1 billion in 2019. These nations, which include over a billion people, received 2% of global FDI in 2018 – almost as much as all the FDI that Italy received that year! FDI flows to Africa declined by 10% in 2019 to the ridiculous figure of $45 billion for a continent of 1.2 billion people.

The more these nations stagnate in the wars and corrupt governments that poverty naturally breeds, the more reluctant capital is to invest in these nations, and the poorer they become. The more that nations need employment and economic growth, the less likely they are to get it under the capitalist system. FDI remains for a select group of rapidly developing low-wage nations like China, but such nations represent the exception among low-wage nations.

This global process in a certain sense repeats the past. In the 19thcentury, there was also much hype around the ‘economic miracles’ of certain Latin American and west African nations. But within a few decades, their economic growth, founded on the exports of commodities produced with cheap labour (or simply slavery), came to an abrupt halt, and capital abandoned the nation to leave it just as poor as before this ‘industrialization’. The same thing happened in certain African nations between the 1920s and 1960s, with the growth of various export-oriented light induxstries very rapidly ‘industrializing’ many nations. But from the 1950s onwards, this inflow of capital was once more replaced with the usual net deficit[30].

A low-wage country is perfectly capable of remaining in its ‘comparative advantage’ of a low-wage processing point. This has been the situation of Bangladesh, for instance, over the past 4 decades or so. After all, this is why the capital came there in the first place, and it already has high-wage consumer outlets in the imperialist nations. The World Bank boasts that ‘nearly every car made in Germany is made with parts from Ukraine’. But these parts – transistor wires – are extremely labour intensive, use very cheap labour power, and their price correspondingly forms a miniscule part of the cars assembled in Germany. Meanwhile, free trade with stronger nations has led to Ukraine’s largest automobile factor, the Zapororozhskij Avtozavod, only producing 1% of its production capacity in 2017, and wages remain around 20 times lower than in high-wage nations.

This is the reason for all those so-called ‘perverse capital movements’, where capital, disobeying Ohlin’s ‘law’ that capital should leave the capital-endowed (high-wage) nations for the labor-endowed (low-wage) nations, in fact performs the opposite movement. As long as the markets of some nations are far bigger than the rest, capital will choose to invest its funds in markets with good investment opportunities. It is entirely natural that whatever money is made in the low-wage nations finds itself in a bank account in Cyprus, which in turn, for instance, heads for real estate, financial investments or productive investment in London, New York or Germany. Every year, $88.6 million leaves Africa as illicit capital flight, which is 3.7% of the continent’s GDP and more than yearly combined official aid and FDI. The only way to keep the funds produced inside a low-wage nation is by taking control from capital

Second, capital in low-wage nations does not feel constant pressure to technologically modernize or train the workforce to maintain profit rates, while the opposite is true in high-wage nations. When wages are at a low level, there is little interest in radically modernizing the enterprise, since good profits can be earned by simply relying on low-wages, which is often much more attractive in the short-term (which is how capitalists tend to reason) than expensive technological investments which take a long time to become profitable. As Ricardo already noted in the 19th century, a businessman only implements a machine if it costs less than the labour it saves[31].

Assume that all capitals in a particular industry have the following structure:

20v + 30c = 70. Rate of profit = 40%. Assume that this 20v pays for 20 workers per year, so each worker has a wage of 1v.

Now assume that capitals in Australia are subject to constant wage increases due to the strong trade union movement there, which is not so violently repressed as in non-white colonies such as India or black South Africa. Wages thus double here per laborer, resulting in the following situation, given the same volume of employment:

40v + 30c = 70. But there is no longer any difference between production costs (40+30) and selling price (70). Australian capitals are making no profit.

To solve this situation, unacceptable for profit-seeking capitalists, labor-saving technology must be introduced. The remaining laborers must also be trained up, in order to better use this more advanced technology. The laid-off laborers can then be employed in the rapidly growing retail sector to service the wealthier workers. We hence return in Australia to the previous profit rates, to:

20v + 30c = 70, with the difference that now only 10 workers are employed.

The low-wage nation can use less productive techniques for the same profits, but the high-wage nation is forced to introduce more productive techniques in order to remain cost-competitive.

The pressure of high-wages is hence a crucial factor in explaining the tendency for high-wage nations to dominate the commanding technological heights of the world economy[32]. One important reason why increased productivity can be highly useful for the high-wage nations relates to the cyclical nature of the capitalist economy. Once a boom period turns into a bust period, with the supply created for the boom-period proving too much for demand and with the market hence becoming highly competitive, the capitals with the most advanced productive techniques will be best placed to succeed. In such periods, demand may suddenly change, and the capitals with the most advanced technologies will be best able to begin producing the new commodities in demand in the new market conjuncture.

Another problem of low-wages determining a choice in favour of labor-intensive, relatively unproductive techniques is that it means that the capital in question is only competitive qua more capital-intensive capitals in the same sector if wages remain low in its nation. If wages increase (which, after all, is the claimed goal of any development policy), then the labor-intensive capital ceases to be competitive[33].

This is the most important way in which low wages constrict economic development in a capitalist economy. There are isolated cases in which low-wage nations use extensive state intervention to become competitive in more capital-intensive products, such as China. However, this nation is meeting with extremely harsh resistance from the rich nations for choosing to abandon its factor endowment – to exit the ‘ghetto of labour intensive production’[34]. If left to organic market mechanisms, as most low-wage nations are, what we have described holds true. And most importantly, the limited demand of the high-wage nations means that only a small minority of the poor world can build its economy around exporting to the former.

Third, high wages and its higher-valued economic product provide a much greater basis for taxation used in crucial unproductive expenditure like education, R&D, and the military, not to mention social spending. For instance, the USA, a nation which has long had some of the highest wages in the world, has funded up to 69% of annual global R&D spending since WW2, and in 2017 the US share of global R&D was 27.7%. Where education and investment in scientific research and development ensure that a nation uses the most advanced productive techniques to succeed in competition, military expenditures (apart from generally vitalizing a capitalist economy) are fundamental in maintaining one’s position of dominance in the imperialist world.

Finally, the most skilled workers tend to emigrate from low-wage nations to high-wage nations because they tend to have the financial means to do so and because high-wage nations make it easier for them to immigrate than for unskilled workers. This brain drain naturally primitivizes the economy of the low-wage nations, as well as generally lowering average incomes[35]. When a nation is filled with unskilled laborers, this naturally attracts capital which is looking for cheap laborers for use in labor-intensive production, and so the function of the nation becomes to be a low-wage processing center for the high-wage nations.

Trade and unemployment

The effects of trade on employment are some of the most important factors in creating and maintaining the global division of labour we have described. We have seen how the high-wage nations out-compete the low-wage nations in most commodities due to the more advanced productive techniques of the former. This means that when the low-wage nations enter into free trade with the high-wage nations, the industry of the former is inevitably destroyed. Free trade is characterized by absolute advantage, not comparative advantage, as liberal economics pretends. By decimating local industries, free trade results in chronic unemployment and underemployment (the WB calls it ‘vulnerable employment)[36] in the poor nations. This unemployment, by saturating the labor market, makes wage levels even more resistant to increases and can even push them absolutely downwards.

Desperate for any employment, the poor nations thus take whatever it is that the rich nations wish them to produce. Naturally, the rich nations want them to continue producing goods cheapened by their low-wages. It is also more rational for the capitalists of the low-wage nations to specialize in labor-intensive sectors, since the high-wage nations are already more competitive in capital-intensive production. Hence the imperative of the imperialist theory of trade – low-wage nations should specialize in their ‘factor endowment’ of labour-intensive production. They should produce the goods whose price is most affected by the cost of labour-power.

Labour-intensive production, although employing more living labour per unit of capital, is incapable of ensuring as much employment as capital-intensive production. Capital intensive production employs not only those who work at the single enterprise in question, as labor-intensive production does. It also employs those who produce the means of production used in this enterprise. There are objective limits to how much labor is necessary for a given labor-intensive enterprise, but mechanization and the new employment it calls into being constantly overcomes previous limits. It is in large part for this reason that nations have always strived to specialize in more and more capital-intensive sectors.

It is in the relation of trade to employment that we can also see the imperialism of commerce at its simplest. A capitalist economy, if closed off from external trade, runs into demand-based limits and is unable to continue expanding investment and hence employment[37]. But given external trade, stronger nations can force weaker nations to buy the commodities that could not be easily realized within the single nation. It is for this reason that trade surpluses have always been associated with national prosperity and high employment rates.

In turn, the trade deficit nations find employment wiped out by these superior imports, and consequently in a constant state of economic stagnation. Instead of productive investments, they end up spend

The necessity of the division of the world into low- and high-wage nations

Without the division of the world into rich and poor nations, all nations – instead of only the low-wage nations – would be in a condition of mass unemployment, starvation wages, and capitalists unwilling to invest. It is not the ‘underdeveloped’ nations, which represent around 85% of our world[38], that are exceptional for capitalism – it is the overdeveloped nations that are an aberration.

The natural condition of capitalism is poverty. This is due to the central contradiction of capitalism: on the one hand, constant wage increases are highly beneficial for capitalism. They expand the market, creating more varied investment outlets and encouraging technological progress. On the other hand, their potential to cut into profit rates (if these wage increases are not accompanied by sufficiently cheap technological modernization, which does not always exist) leads to a tendency to push wage levels down[39]. The system ‘tends to choke itself’[40].

In the 20thcentury, and already beginning before that, capitalism inadvertently created the illusion that it could allow for mass prosperity, when wages rose in certain countries under trade-union pressure. This political deviation from capitalist economic logic fundamentally transformed the system. It came at the price of repressing wages in the rest of the world. T

Social democratic is necessarily imperialist, because if the capitalists of a certain country are forced to allow wage increases, then it becomes extremely important to make sure wages are low elsewhere. This is due to the importance of the rate of profit in a capitalist economy. If non-wage elements of production (for instance, means of production or raw materials) are imported and cheapened by unequal exchange, then the fall in the rate of profit caused by wage increases can be offset[42]. Wages can be allowed to grow in a handful of countries if the rest of the world exports products made on starvation wages.

In the past, wages were kept low through direct colonial domination. Today, wages are mainly kept low through competition to gain access to the markets of the high-wage nations. Low wages are also more directly enforced outside the imperial core through the policy conditionalities of financial institutions controlled by the high-wage nations, such as the IMF and WB. The low-wage nations are often dependent on their credit, due to the economic weaknesses resulting from low-wages we have described.

A second reason that high wages in one country require low wages in another is also related to profit, but also to the commodities that money wages are spent on. If wages are high in one country, then the capitalists of that country can avoid drops in the profit rate (or can even increase it) by decreasing money wages or allowing them to stagnate, but ensuring that purchasing power (real wages) stay the same or even increase by importing underpriced consumer goods[43]. This is what the US and other imperialist nations have done in the past decades by exploiting China[44], but it has been a crucial factor since capitalism’s mercantilist beginnings. It is through this that the imperatives of profit and of internal political stability can be temporarily balanced. Internal contradictions are displaced onto the international scale.

A third important aspect of contemporary imperialism relates to the supply of cheap migrant labour. The unemployment created in poor nations by free trade creates a large population of people desperate for any work, at any price and in any conditions. Although the core-nations are only willing to absorb a tiny proportion of these masses, leaving the rest to starve, die in their journeys, be killed or sold by slavers and so on, they also have good reason to put some of them to work. The high wages in the imperialist nations make many economic activities unprofitable.

Meanwhile, nations lower down in the hierarchy of nations often find themselves faced with a general labor shortage, as their workforce disappears to work in the richer nations, or is simply unwilling to work the most difficult and worst-paid jobs due to better opportunities in the richer nations. This possibility of creating a mass of unemployed workers willing to migrate in search of work is another motivation for relatively richer nations to force poorer nations to trade with them.

Conclusion

The high-wage nations have good reasons to demand the low-wage nations to open up to free trade, at the same time that this promises indefinite, mass unemployment for the latter. Being thus desperate for any employment, the low-wage nations are incapable of doing anything other than specializing in the commodities that the high-wage nations need, cheapened by the low wages involved in their production through unequal exchange. In turn, low wages encourage a range of forms of economic underdevelopment. Even cheap-labour-seeking investment usually never comes, and the country, wracked by unemployment, is stuck forever in stagnant poverty and the self-destructive violence this engenders. Any end to this situation requires a break with the imperialist world-economy and capitalist economic logic.

Notes

- ^ IMF (p. 7, 13), World Bank (p. 68—71).

- ^ SeePrinciples of political economyand taxation, 1817 “On Foreign Trade”

- a, b Emmanuel, Arghiri 'Introduction', in "Unequal Exchange", 1971. Shaikh, Anwar 'International Competition and the Theory of Exchange Rates', pp491-538, in "Capitalism: Competition, Conflict, Crises" 2016

- ^ See moreon the problems of the Ricardian theory of comparative advantage, which still dominates economic theory of trade

- ^ As cited by Shaikh (2016), page 500. See this same chapter fora theoretical argument, empirically demonstrated, why exchange rates are not determined purely by the quantity of money in a nation.

- ^ Paul Samuelson and Eli Hecksher are also commonly associated with Ohlin, but we will focus on Ohlin here.

- ^ Ohlin, 1935, International and interregional trade, pp. 36

- ^ UN 1999 Cited in cope, divided world divided class 228

- ^ “Is global inequality getting better or worse? A critique of the World Bank’s convergence narrative” Jason Hickel, Third World Quarterly, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2017.1333414

- ^ With the exception of Japan and, to some extent, South Korea.

- ^ the Gulf oil states are excluded.

- ^ As cited in Suwandi, Intan (2019), Value Chains: the New Economic Imperialism, p54

- ^ Cope, Zak (2019)Wealth of (Some) Nations, p69

- ^ SeeUnequal Exchange 1972, and for a shorter summary, ‘Unequal Exchange Revisited’ 1976

- ^ Capital Volume 3, Marx, “Chapter 10: The equalization of the rate of profit through competition. Market prices and market values”

- ^ Capital Volume 3, Marx, “Chapter 9: The formation of a general, or average rate of profit and the transformation of values into prices of production”

- ^ For data on the rate of profit in China and the USA see Minqi Li, China and the 21stCentury Crisis, p79. In more recent work Profit, accumulation, and crisis in capitalism : long-term trends in the UK, US, Japan, and China, 1855-2018 (2020), p84, he calculates that the rate of profit in China has, since 1980, fluctuated between 10 and 25%.

- ^ Min qi Li, Rise of china and demise of the capitalist world economy, p109

- ^ There are a variety of attempts to calculate the amount of value lost by the low-wage nations due to unequal exchange. See: Ricci (2014), ‘Unequal exchange in the age of globalization’ for a sophisticated recent attempt.

- ^ See for Prebisch’s classic statement of the argument. William Milberg and deborah winkler, 2010, Economic and Social Upgrading in Global Production Networks: Problems of Theory and Measurement, Capturing the Gains working Paper 10, Capturing the Gains (CtG), Convenor: Stephanie Barrientos, university of Manchesterfor a Prebisch/Singer inspired analysis of contemporary economic development in the low-wage nations

- ^ unCTad, The Least developed Countries Report 2004—Linking International Trade with Poverty Reduction (Geneva, unCTad), 126–27.

- ^ To be more precise, the net barter terms of trade, the percentage ratio of the export unit value indexes to the import unit value indexes, measured relative to the base year

- ^ For instance, much of China’s ‘industrial upgrading’ is nothing of the sort – instead, it just imports the technologically advanced inputs from South Korea or Japan, and then does the labor-intensive manufacturing at home. See Smith (2016) Imperialism in the 21stCentury, p89.

- ^ Data from [link], cited by Smith (2016), p96.

- ^ Smith (2016), 96

- ^ [1]Immense protectionism is afforded to the industry, particularly the agriculture, of the high-wage nations, protectionism forbidden for the low-wage nations. For instance, around 60% of the total value of OECD agricultural production was protected by state subsidies and trade barriers in 1999, at the apex of ‘free trade’ (as cited by cope 2012 p140). To this day, it is rare not to read a UNCTAD or WB annual report which does not begin by pathetically imploring the EU and the USA to consider stop heavily subsidizing and otherwise protecting its agriculture. Cope (2019), p228 – ‘The World Trade Organization (WTO 2017) states that poorer exporting countries such as Cambodia and Bangladesh face tariffs 15 times higher than those applied to wealthy nations and oil exporters, while consumers and governments in rich countries have paid US$350 billion per year supporting agriculture – enough to fly their 41 million dairy cows first class around the world one and a half times.’

- ^ Data from UNCTAD 2020 investment reportp238

- ^ Based on 2019 population, where developed world is the list of nations given by UNCTAD in the 2020 Investment Report

- ^ UNCTAD 2020 world investment report, 124

- ^ Emmanuel, Unequal Exchange375

- ^ On the Principles of political economyand taxation p31, «Chapter 1 On Value, section IV. See also Emmanuel, Appropriate or Underdeveloped Technology, p77

- ^ [1]See Smith 2016, p89-92.For more on how the high-wage nations dominate the production of the most technologically complex commodities, see Appendix C Arnelyn Abdon, Marife Bacate, Jesus Felipe, and Utsav Kumar, Product Complexity and Economic Development, Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 616 (2010)., or Hausmann the Atlas of Economic Complexity

- ^ Appropriate or underdeveloped techniques p91-2

- ^ phrase from emmanuel, myths of underdevelopment

- ^ See p156 of Smith, 2016

- ^ ‘Employment’ in seasonal agriculture or informal service sectors (selling cabbage or trinkets on the street), for instance. The prevalence of such forms of underemployment is known to depress wages in much the same way unemployment does, see Kerswell, TImothy, “Productivity and Wages: What Grows for Workers without Power and Institutions”, Social Change, 43, 4 (2013): 507–531.Smith (2016), 115 for statistical evidence on how the absolute rise in employment in the low-wage nations over the past 3 decades has also seen no tendency towards increased formalization of labour – instead, informal employment has often tended to grow faster than total employment.

- ^ See Emmanuel’s Profit and Crises for an important analysis of the capitalist economy’s structural tendency towards overproduction, and how this contradiction is temporarily relieved through trade imperialism.

- ^ High-wage nations with significant populations = US, Canada, Republic of Korea, West Europe, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, + other small nations considered part of the ‘developed world’ by the UNCTAD in 2020 development report previously cited

- ^ For an extended analysis of this central contradiction of capitalism, see Emmanuel’s Profit and Crises(1986)

- ^ Profit and crises page 376

- ^ See Zak Cope divided world, divided class on the ‘active policy of social imperialism consciously pursued by the imperialist ruling class’ (94) due to pressure from the domestic working class in the 19th and 20th centuries, 94-99.

- ^ See Brolin, John (2007) The Bias of the World Theories of Unequal Exchange in History, p183 for a helpful demonstration of this process

- ^ For contemporary empirical proof of this fact: IMF (2007) World Economic Outlook (WEO) — Spillovers and Cycles in the Global Economy, 179; Smith, John “Offshoring, Outsourcing and the ‘Global Labour Arbitrage’,” paper to the International Initiative for Promoting Political Economy (IIPPE) 2008, Procida, Italy, September 9-11.; cope 2012 p104-10; Heintz 2003 the New Face of Unequal Exchange; Patnaik 2007 The Republic of Hunger and Other Essays, 25 – ‘as much as 60-70% of Northern food items have tropical or sub-tropical import content’. For an analysis that identifies this mechanism of imperialism as a condition in the birth of capitalism, see Ruy Mauro Marini 1969 La dialectica de la dependencia

- ^ See Minqi Li’s (2020) Profit, Accumulation, and Crisis in Capitalism Long-term Trends in the UK, US, Japan, and China, 1855–2018, p94 for calculation of the saved costs for the US economy due to underpriced imports from China. He calculates that at its historical peak in 2006, these savings represented 2.2% of US GDP and 16.9% of manufacturing value added. He makes the same calculations for the UK and Japanese economies on p100 and p104.