In 2020, when I conducted my ethnographic fieldwork in Crimea, few expected it to be de-occupied any time soon. In mainland Ukraine too, the saying “next year in Bakhchisaray” sounded naïve and awkward as those who uttered it understood their self-deception perfectly well. Yet, three years later, de-occupy Bakhchisaray is becoming a real possibility. Moreover, many commentators argue that “there will be no peace without Crimea”, and the majority of the Ukrainian population support the idea of the peninsula's de-occupation.

So it makes sense to think deeply about our relation to the peninsula and people who live there, especially the indigenous Crimean Tatars. The Ukrainian state and society need to clearly understand the nature of this relationship and the basis for Ukraine’s rule there. Such understanding should lay at the core of the wholesale strategy of Crimea’s reintegration. Its failure to do so in the early years of independence partially led to the annexation of Crimea, and we cannot afford to miss the second chance to make things right.

The Crimean Tatars: From Political Negligence to Recognition

Prior to 2014, Ukrainians who did not have much attachment to Crimea except for summer vacation memories did not care much about the peninsula and the Crimean Tatars. The Ukrainian state too misinterpreted the difficult postcolonial situation in Crimea wrongly putting the blame on Crimean Tatars for “inter-ethnic” instability. That gave pro-Russia and Russia-sponsored groups free reign to do whatever they wanted, from training paramilitary Cossacks to buying out the entire south coast of Crimea. Ukraine’s lack of strategic vision and attention to Crimea made it easier for Russia to annex the peninsula.

Today, as the Russo-Ukrainian war is seen by many as an anti-colonial war, it is natural that the de-occupation of Crimea should be understood as part of the wholesale process of decolonization. Yet true decolonization cannot happen without us understanding the dynamics of power that formed in Crimea both in distant and recent history, and our own role in perpetuating it.

A Russian soldier without identification marks near a military base in the Crimean village of Perevalne on March 20, 2014. Photo: REUTERS/Baz Ratner/File Photo

The first steps toward this have already been taken by the Ukrainian government that since 2014 adopted a number of policies that finally recognized the historically oppressed Crimean Tatars as indigenous people, who had been living in Crimea for centuries well before Russia colonized it in 1783. The policies acknowledged the right of the Crimean Tatars for self-determination, legitimized the democratically-elected self-government bodies Mejlis and Kurultay, recognized the deportation of 1944 as genocidal, among other measures. Ukrainian social scientists, writers, and journalists, who previously ignored the issue of the Crimean Tatars, now center them in their works, emphasizing especially Ukrainian-Crimean Tatar encounters. Ordinary Ukrainians too, put effort to learn more about the Crimean Tatar culture and extend their solidarity to the displaced people. While these efforts essentially reverse the decades of ignorance and epistemic injustice, the solidarity seems to end when the question of Crimea’s status begins. Ukrainians gladly go to “Musafir”, a popular Crimean Tatar restaurant in Kyiv, yet hardly ever seriously contemplate the Crimean Tatars’ demand for autonomy or other forms of self-determination.

The question of Crimea’s status after the de-occupation will inevitably arise and unfortunately, we are not ready to answer it. Why is that?

Whose Crimea? Historical Revisionism and International Law

First of all, undue emphasis has been put on historical revisionism that seeks to justify Ukraine’s claim to Crimea, instead of historical revisionism that fills in blind spots, interrogates misconceptions, and conceptualizes Crimea’s history and present in post-colonial terms. Secondly, historical revisionism was put to use as a political instrument of legitimization, bypassing a more conventional and undeniable form of legitimization, such as international law. Finally, the question of the form in which the Crimean Tatar self-determination can be actualized is itself controversial and ambiguous both within the Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian society at large.

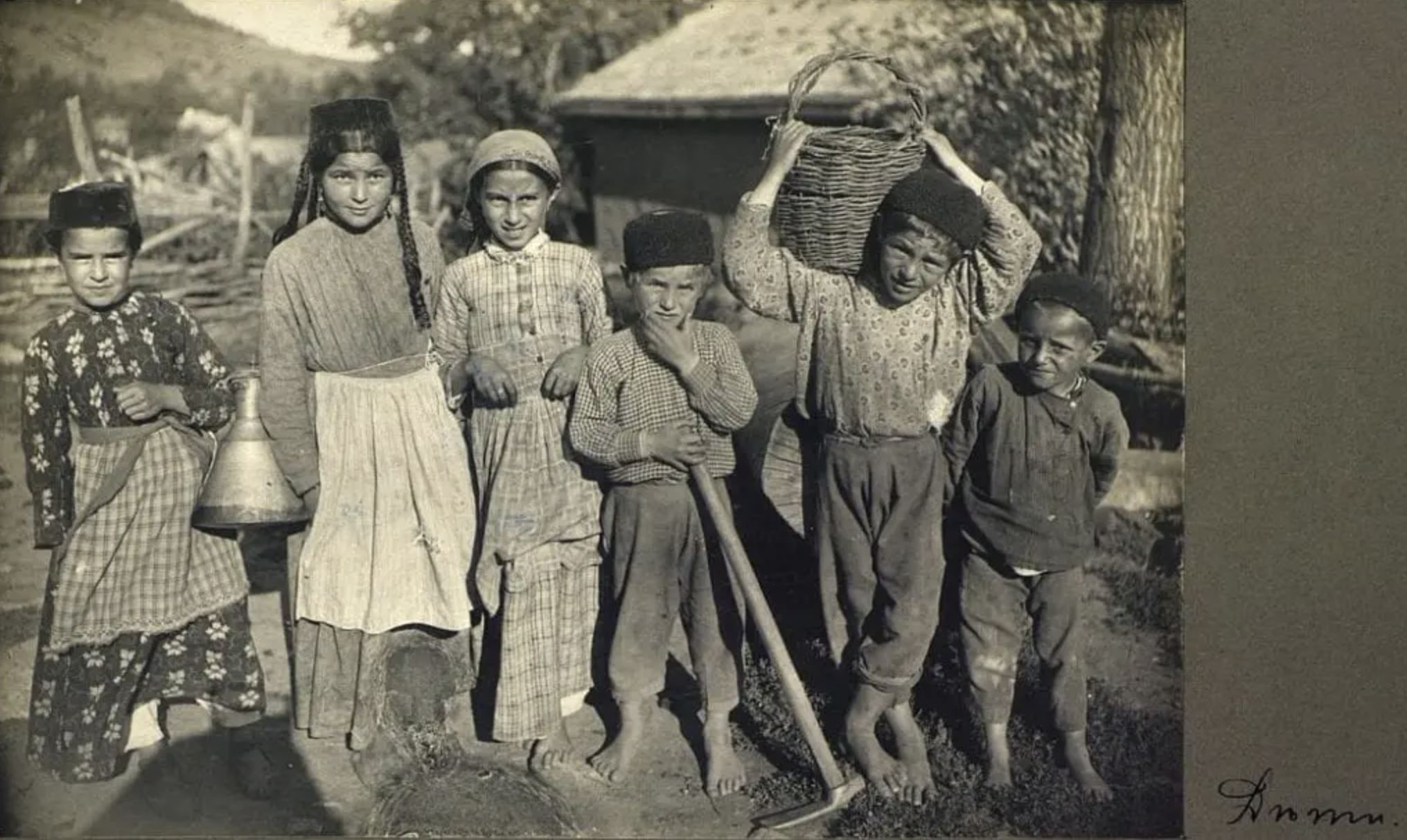

Crimean Tatars of Alushta, 1908. Photo: Wikimedia

Since 2014, the historical scholarship that is at the core of any public discussion on the history of Crimea and its role in Ukrainian statehood followed a Russian propaganda playbook by constructing a parallel narrative of “Ukrainian Crimea”. In their attempts to “debunk Russian myths”, professional and amateur historians, journalists, and writers produced more myths that repeat Russian logic of historical claim to the territory, simply substituting “Russian” with “Ukrainian”. Among most recent examples is Ukrainer’s article “Yalta: a city with a healing climate and cultural resistance”, which proves Yalta’s Ukrainianness by the fact that Lesia Ukraiinka and Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi spent time there, ostensibly making it more Ukrainian by their sheer presence. In fact, literary scholar Rory Finnin in his book The Blood of Others illustrated how both Lesia Ukrainka and Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi saw and depicted Crimea in their novels as Crimean Tatar place, securing the link between the territory and the indigenous people, in contrast to Russian authors, such as Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov, whose 19th century Crimea was completely Russified. Another example is the Ukrainian online-storage of archival, museum, educational and informational materials “Crimea is Ukraine”. In one article entitled “The great resettlement of Ukrainians to Crimea”, the authors claim that it was because Ukrainian “migrants” “labored tirelessly” in the post-war period (1944–1954) that Crimea was essentially “reanimated” and eventually transferred to Ukraine.

The problem with such historical revisionism is that it cherry-picks historical occurrences to legitimize the state's rule over a territory – precisely what the Russian state is doing. The authors do not seek to understand power dynamics and forms of governmentality that are similar to other colonial contexts, instead they try to prove Ukraine’s unique historical claim to Crimea. As a result, the narrative not only is questionable for everyone familiar with the history of the peninsula but also invites contestation between the Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians. As we will see, Ukrainians on average remain hostile to the very idea of the Crimean Tatar self-determination, even if it is guaranteed by international law.

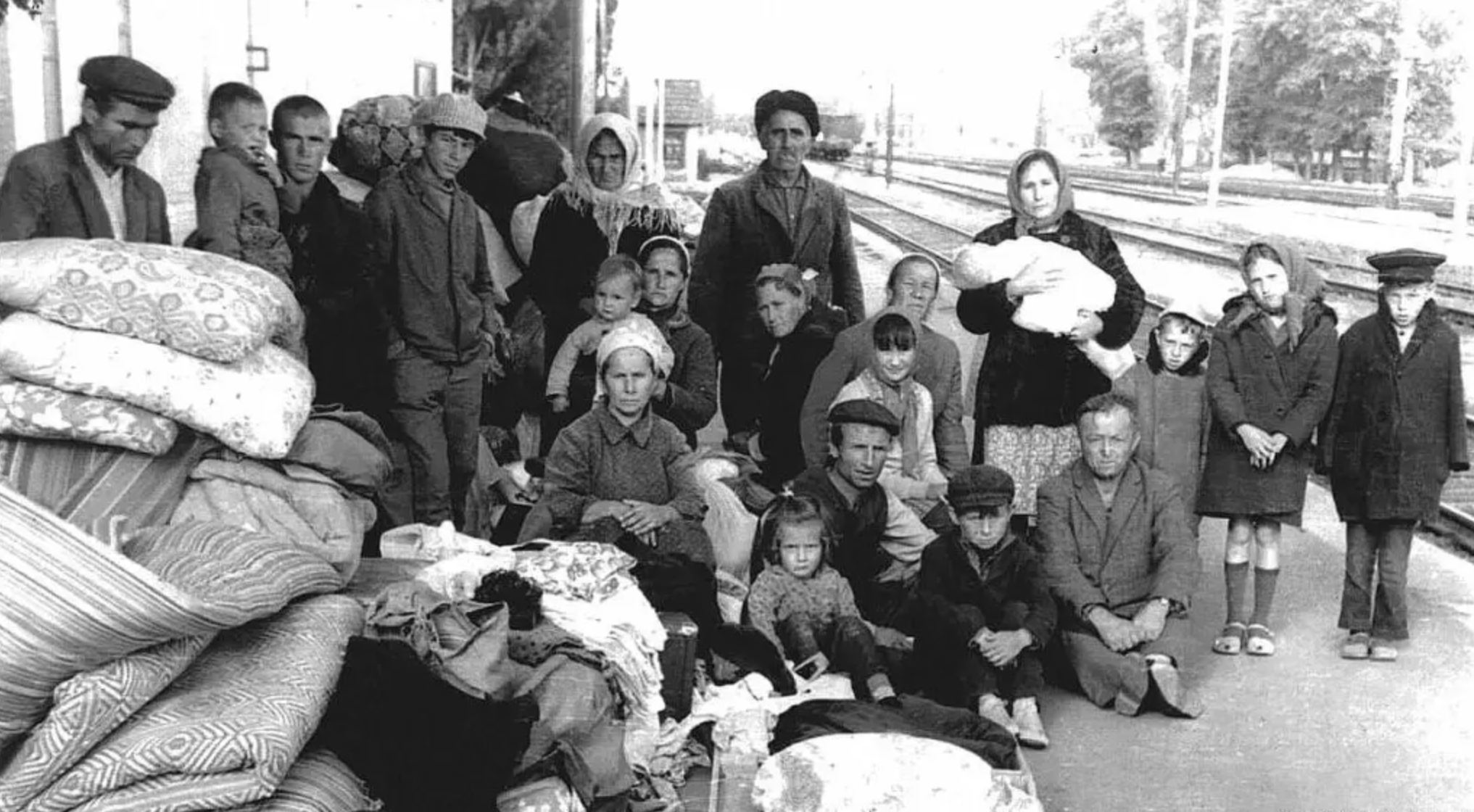

Crimean Tatars who tried to return but were evicted in 1968. Photo: Wikimedia

The fact, however, is that Ukraine does not need to instrumentalize its history and construct narratives to return Crimea – we have international law for that. It is the international law that guarantees territorial integrity and sovereignty that we should appeal to, not history. Similarly, were the international law on indigenous peoples emphasized more, few would have had doubts or concerns about the rights of the Crimean Tatars to self-determination.

Decolonization: Ukraine’s Collective Responsibility before the Crimean Tatars

Ukraine still, however, needs historical revisionism to understand how to relate to Crimea and Crimean Tatars. One such badly needed form of historical revisionism is post-colonial. Conceptualization of Crimea as a settler colony has been advanced by both Ukrainian scholars (Maksym Sviezhentsev and Martin-Oleksandr Kysly) and international (Rory Finnin, Sasha Shestakova & Anna Engelhardt) but it still remains extremely marginal. In this conceptualization, the history of Crimea is a history of colonization, dispossession, and erasure by Russian Empire, Soviet Union, and Russian Federation. The indigenous people – Crimean Tatars – are the main victims of Russia’s imperialism as they for centuries experienced land deprivation, dispossession, ethnic cleansing, and oppression. When they were finally allowed to return in the 1990s, they began the process of decolonization, whereby they tried to reclaim their land (through samovozvraty), regain political voice, and rebuild cultural heritage. Yet, as Rory Finnin states, neither Ukrainian nor (pro)-Russian elites in Crimea admitted the need for restoring justice and framed the conflict in Crimea in “inter-ethnic terms”, glossing over the colonial hierarchies.

Demonstration of Crimean Tatars in Moscow, 1987. Photo: Wikimedia

What is the role of Ukraine in this conceptualization? Ukraine is clearly not a colonialist as it did not conquer Crimea or impose its own statehood. Crimea became part of Ukraine through a legal mechanism for economic reasons, and its population voted in favor of Ukraine’s independence in the legitimately held referendum in 1991. Yet, just because the Ukrainian state did not colonize Crimea, it does not mean that Ukrainians bear no collective responsibility before the Crimean Tatars. Since 1954, the year Crimea became part of Ukrainian SSR, the Ukrainian political elites in Crimea and in Kyiv adamantly resisted the Crimean Tatars’ return to their homeland, as the Party Archive in Kyiv reveals. Hundreds of people who attempted to return back to their homes during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, were violently deported again, thrown out of the houses, denied city permits and registration, among other things.

The settler colonial framework forces us to see ourselves not only as victims of Russian imperialism – which forms a bond of solidarity between Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars – but also as subjects complicit in the Crimean Tatar oppression. When the entire nation was deported in 1944, the settlers from Russia and Ukraine came to occupy the Crimean Tatar houses, use their furniture and dishes, and work in their gardens. The aforementioned article on Ukrainians in Crimea is thus not a proof of “Ukrainian Crimea” but a proof of complicity of Ukrainian settlers who voluntarily went to “reanimate” the land that was forcibly depopulated.

Moritz Webel. The ruins of the Özbek Han Mosque, 1848

Conclusion

The existing revisionist history that seeks to prove Ukraine’s historical presence in Crimea contributed unintentionally to a set of misconceptions and misunderstandings. If Crimea has been historically Ukrainian, why should the Crimean Tatars have any special rights there? How would their status as indigenous people infringe on the rights of Ukrainians or other citizens of Crimea? The discussion is even more complicated since there is no consensus within the Crimean Tatar community on the most desirable form of self-determination: autonomy? special status? affirmative action? Furthermore, considering that the Crimean Tatars in pre-2014 constituted only 13% of the population, what would be the implications of the Crimean Tatar autonomy for the rest of Crimea’s population? Finally, what about other indigenous peoples, such as karaims and krymchaks: should they demand autonomy as well?

Crimean Tatars on the way to the peak of Chatyr-Dag. Photo: Moritz Küstner

These are valid questions and need to be considered seriously. Yet, any such discussion should be based on deep contextual understanding of historical power disbalance in Crimea and on international law, not on ignorance as illustrated by recent statements of adviser to the Head of the Office of the President of Ukraine, Mykhailo Podoliak, who dismissed the autonomous status for Crimea, to the chagrin of many Crimean Tatar commentators. Historical revisionism will help Ukrainians to understand the history of the land we are about to de-occupy and how we should relate to it. The international law will help resolve the tensions between various groups by delineating rights, duties, and privileges, as well as constitutional framework and enforcement provisions.

Many Crimean Tatars are already seriously contemplating their preferable form of self-determination and Crimea’s legal status based on international legal framework. From their political representation in Crimea’s government to the protection of cultural heritage, there are many ways in which autonomy can be realized. The foremost task for Ukrainians, however, is to prioritize the Crimean Tatar voices, show care and respect to people, who today stay side by side with us. After all, the only way the egalitarian and just Crimea is possible is by inclusion of previously excluded and oppressed voices.