"The amazing paradox of the ethnographic moment… is that coming closer to the Other creates a clearer sense of self, and thus opens up ways to know the Other better," emphasizes anthropologist D. Soyini Madison.

In August 2022, a study called ‘The Art of Arriving’ started to explore the experiences of Ukrainian refugees in Austria. The project has been going on since 2021 and previously interviews were conducted with people from former Yugoslavia who had a refugee experience in 90’s, and those people coming from Syria, Afghanistan, and several African countries who fled wars more recently. Ukrainians, contrastingly, were interviewed just a few months after the outbreak of a full-scale war in Ukraine and soon after their arrival, at a time when they were still "hanging" between two worlds and mostly had no clear idea how long they would stay in Austria, what they would do here, or whether they would return home.

In this research, all the participants were invited to talk about the art pieces, created by artists to represent the fate of refugees, and about their experience of displacement in the form of group discussions, with 2-5 people in each.

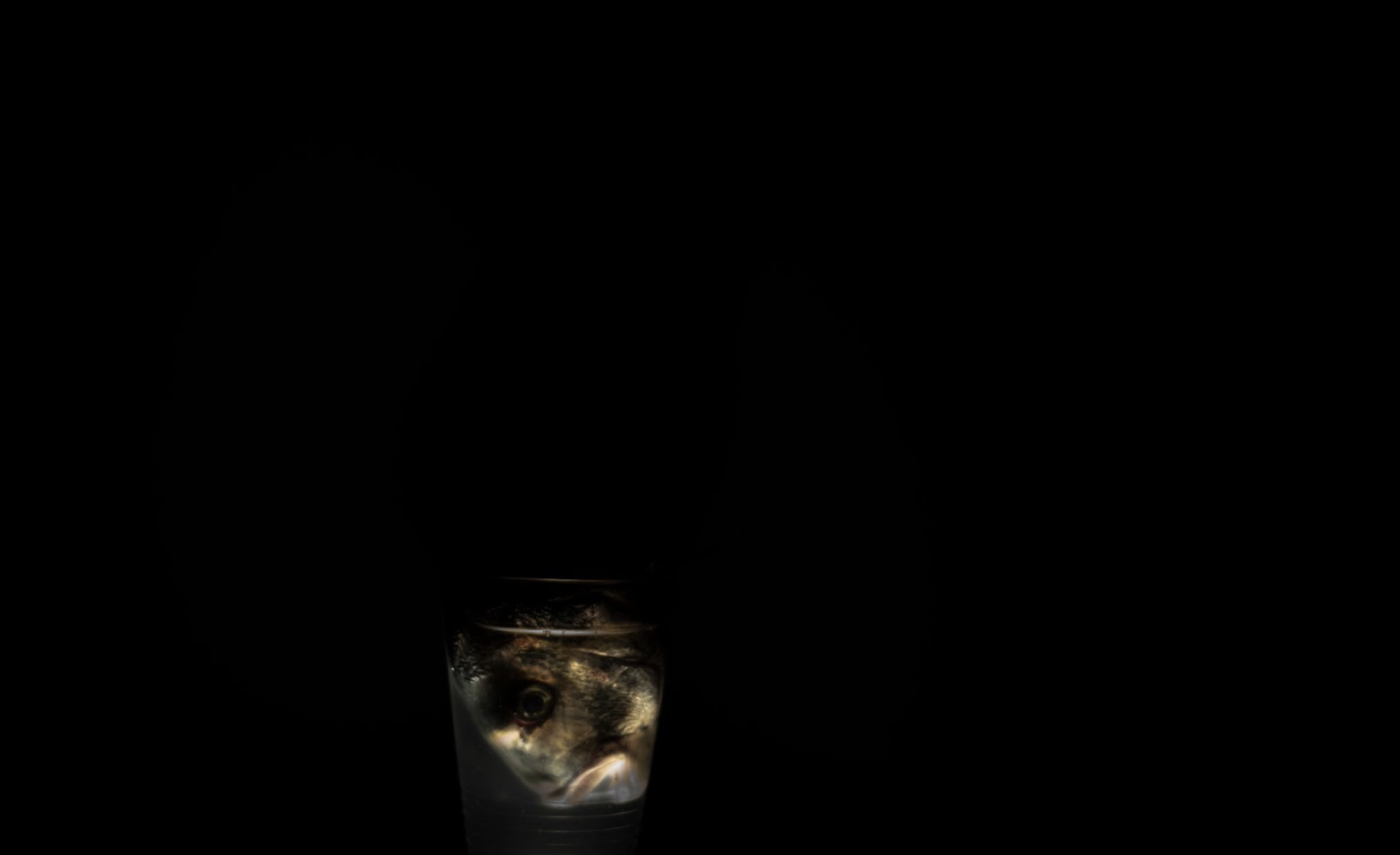

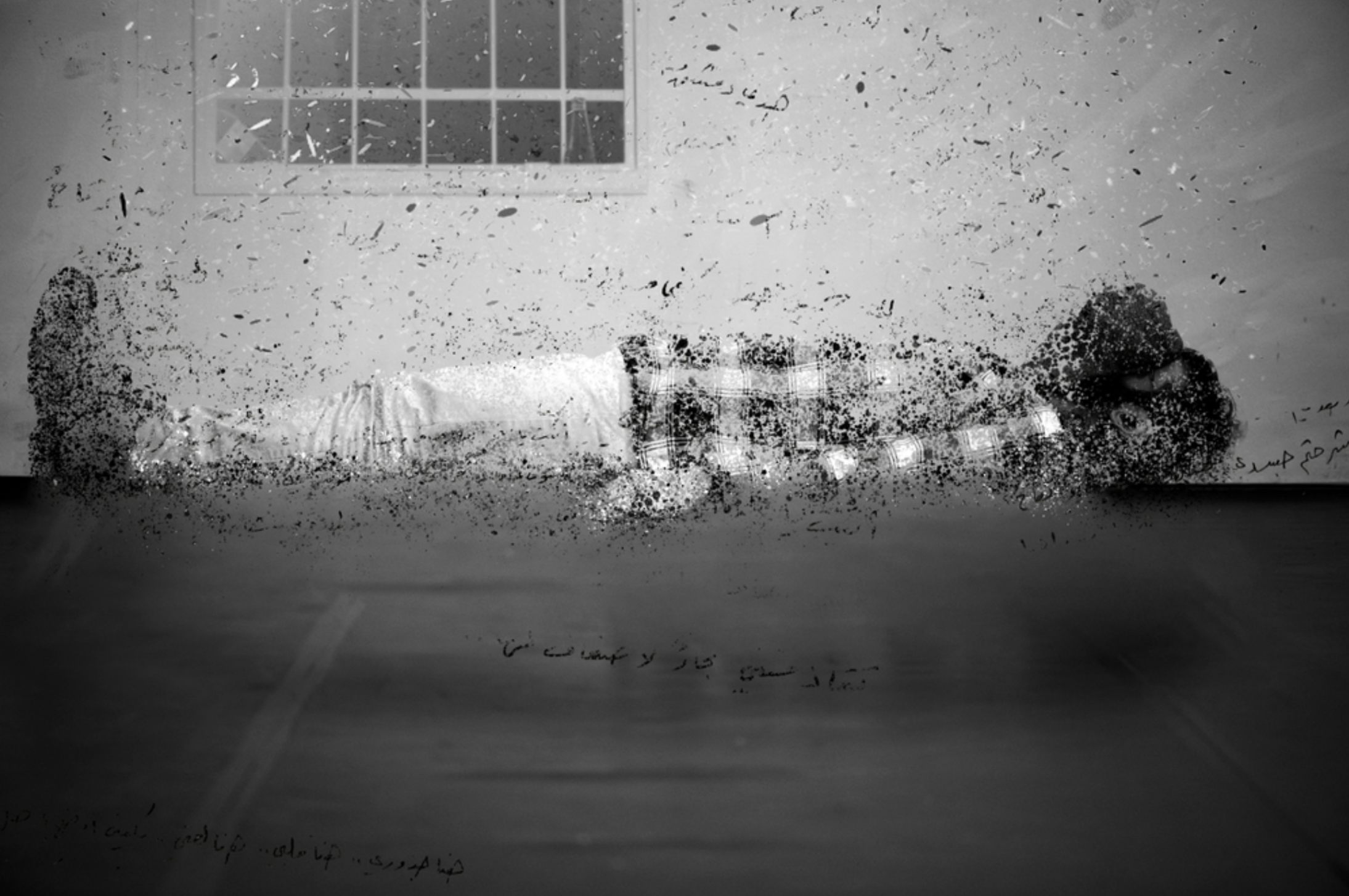

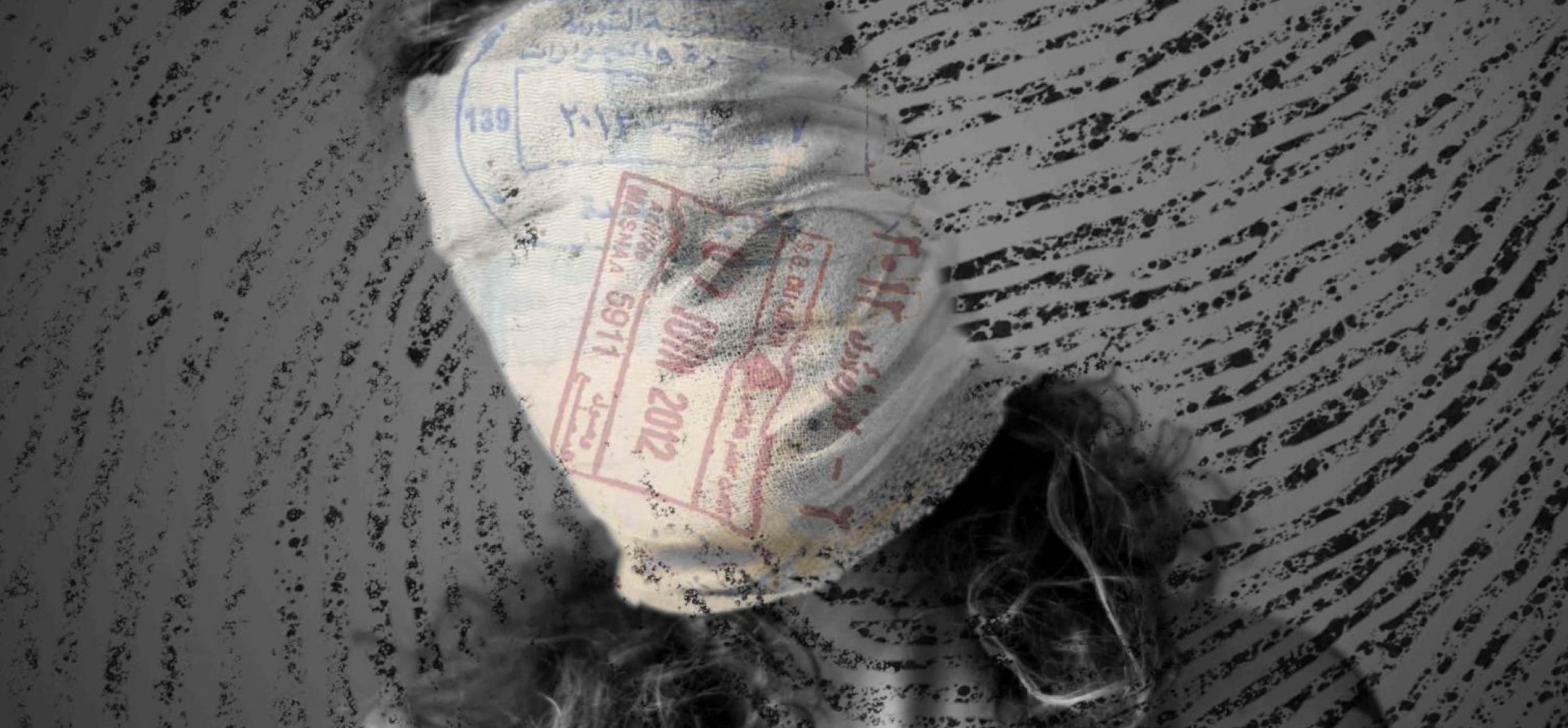

One set of photos presented to the Ukrainians was under the title ‘Fish’. It consisted of five different pictures of a fish placed into a transparent glass. Each photo is edited in a way that presents different perspectives and states of the subject. The second piece was called ‘Mask’. The central figure in this black-and-white image is a woman whose face and hand seem to be made of or covered by plastic, thus disfiguring her image. She sits in solitude in the middle of a modest room setting.

Another item presented for discussion was an instrumental piece composed by Orwa Al Shoufi At first it sounds like a classical European piano melody, which is then repeated on an oriental stringed instrument oud with characteristic for its performance melismatic nuances.

A total of 8 discussions were held with 2-3 participants in each of the groups.

‘Fish’. Photo: Linda Zahra

‘Mask’. Photo: Linda Zahra

At the head of group discussion moderation stood we, two Ukrainians, Liza Zolotarova and Olena Tkalich. In mid-spring 2022 we were invited into the project by researchers at the University of Vienna as part of the Austrian comprehensive support program for Ukrainian scholars. At the time of the full-scale Russian invasion, Liza was enrolled in a Master’s program at the Central European University in Vienna, thus having no direct experience of displacement. However, she spent her school years in Kyiv and has strong ties to Ukraine. Olena found herself in Vienna with her two children in March 2022 as a direct result of the war. So she received both official EU protection status and the relevant experience of interacting with the bureaucratic institutions involved in the reception of those feeling Ukraine.

During one of our mundane discussions we generated a seemingly commonsensical assumption that our origin and background had a special and critical role for this study. For one, it appeared self-evident that our knowledge of the language and the general socio-cultural contexts from which the respondents were coming had a special value in this endeavor. First and foremost, this probably had a substantial impact on the recruitment, style of engagement with the participants and consequent analysis of the collected data. However, against the backdrop of the calamities experienced in Ukraine, the connection runs much deeper. Although we are all exposed to various versions of how the war is experienced, a common sense of loss and utter disorientation adds a level of familiarity and sincere compassion.

Generally, after every encounter with the participants, there was a pervasive feeling that these meetings were filled with a sense of trust and comfort. Several participants noted that they felt better after the conversations, that our meeting helped them to better understand themselves and their perspectives. And we ourselves felt a certain degree of relief in relation to the matters of the new reality brought about by the full-scale invasion. Here, using autoethnography, we try to acknowledge how deeply sensitive and personal research in sociology may be, and hint at why and how this aspect can be integrated into the development of research design and reflected on in the findings.

What is the autoethnographic method and where is it used?

The main feature of autoethnographic approaches is that it puts the subjectivity of lived individual experience at the center of the research and is based on the assumption that critical and systematic analysis of our own narratives can provide insight into the culture of which we are a part and its place in our identity.

Photo: Linda Zahra

At the same time, autoethnography accepts the understanding that we actively interact with the reality around us, and not just passively internalize everything it offers us. This is because the features and characteristics of our identity are constantly being shaped and reinterpreted in the interaction of social structures and subjective processes (R Student, Kendall K. & Day L. 2017).

Therefore, perhaps, a certain kind of "relief" experienced by some participants and ourselves stems exactly from this peculiarity of identity formation processes.

As we cannot speak for other people on whether our interaction had an impact on them, we chose this approach to describe our personal observations and thoughts on this matter.. This appears especially relevant as constant reflection on our own role, position, and status in the discussions is implied by the research methodology of the project. This way, the idea of the possible "therapeutic effect" of group discussions came primarily through our conversations, as well as during the reflection sessions with the team. In this process we also discovered that the most pressing personal issues touching a cord in us were loneliness, isolation, constant self-control, worries about the loved ones, and the loss of chances for a decent life.

Liza's position: Not like a fish in water. Loss of self and chances for a decent life

“How great is it to be working with sociologists! It is them who are generally aware of the complexities of the experiences people affected by crises face.” This thought fills my mind again and again, at work, and in the most mundane of settings. And I experience a relentless sense of gratitude to this work, to the solace I found with it. And can’t help but grow in the conviction that this research has had a notable effect on those involved.

I observed how a dialogue can be conducted, how it is possible to exchange experiences and understand each other, even if outside of this context it might seem that people would never listen to each other. It is in an interaction between the participants and ideas and descriptions of the subject would be born. Also, it appeared that the obstacle of suspicion was overruled . People shared that often they feel one is more likely to expect condemnation from strangers. While support generally only comes from the closest connections. Yet here, in this room, we had strangers who were immediately able to listen and hear each other. Observing these conversations allowed me to better understand my own experiences.

Working in this project revealed several most pressing topics that occupy my mind and cause most discomfort and disquiet. Primarily, these concerns are about social atomization and a sense of distrust, but also the question of life prospects, their acquisition, and loss – now these are the most acute issues for me.

Photo: Linda Zahra

I was most touched by a woman who appeared very similar to my mother – about the same age, profession, and with similar experiences. This is Olha (hereinafter all names have been changed), a pre-retirement participant from Odesa with a medical degree who came to Austria to her daughter after the war started.

Olha broke down in tears during the group discussion and spoke painfully about her inability to find a decent job here. Eventually, she decided to return to Ukraine and bought tickets home a few hours before our meeting. She speaks:

"When I realized in what kind of roles I could work here, it was, of course, just very scary, very scary. Because when you live your whole life and have an occupation, achieve certain things, some success for yourself, and at one point it all collapses, you realize that it is, of course, very disappointing. (…) You realize that you are coming to a different country and that people, and society here live their own life, as they’re used to living this way. And society here is not responsible for the fact that you find yourself in this situation. Yes, it is ready to help you, to support you, but it will be a sip of water in a glass, nothing more," Olha said.

Since I was not physically in Ukraine when the war started, I felt the gap between reality, fear, and rage through the experiences of my loved ones. Luckily, they were safe, but the war undermined their prospects for decent life.

With time, it can be difficult to remember what caused the most despair. However, now, or perhaps it is exactly now, the thought that my family can lose everything or much of what they have to create is at times excruciating. All those possessions were created with great effort. The thought that their lives, the past and future, have been ravaged by the war makes me angry and desperate.

I think I have a certain vision of life, in which it appears natural that a person accumulates certain “capital” as he or she progresses. These assets are in the form of the entire complex of cultural capital: professional dignity, personal and professional connections, and material possessions that are supposed to alleviate hardships. It is also a vision of the future. But now it is broken and needs to be reassembled from fragments and shatters. The realization of a terrible annihilation of the years of efforts burns and opens an abyss of despair.

And then I saw a person who seemed to me to be in a similar state to my closest people from many points of view. Observing the way she thinks about how to move forward, how she makes important decisions and copes with the new reality gave me strength and some confidence that people like this can always find a place for themselves. With my family far away, it was also probably an opportunity to live my feelings in close physical proximity to a person towards whom I am particularly empathetic.

It turned out that for some of our participants as well, the loss of life prospects was closely related to loneliness.

"You collapse as a person because you are a person only in the eyes of your friends. And here you are nobody. Until you show a piece of paper saying that you're some expert," said Bohdana, 28 from Kyiv who found herself alone in Austria. She said she had completely forgotten that she had a number of achievements in Ukraine: "I just recently remembered that we started our business… "Damn! I was starting a business! What!" I forgot about it… And that we started recording an album. I was recording an album! I had a production project! How could I forget these!"

At times, the sense that a life “there” has been obliterated is relentless, blinding, tragically disorienting.

Photo: Linda Zahra

Olena's position: To be silent like a fish. Loneliness and isolation

The breakdown of usual ties, loneliness, and separation from my husband – this is what depressed me the most, apart from the general shock from the horror of war. After crossing the border, it was as if I lost contact with reality. The real world was only on the phone screen, and the world around me was a mere background. That's why I was most affected by the stories of how people experience this sense of split reality and how they try to overcome separation and isolation.

One of the participants, Oleh, who left Ukraine for medical reasons and who now supports his elderly parents and a seriously ill brother, spoke about his connection with his school friends from Kharkiv. It was important for him to find a way to stay with them and his hometown.

"My friend set up a camera, streamed it online so that I could at least follow along, and I fell asleep listening to the shelling with my friends, because it was so much easier for me to sleep and at least hear the shelling, at least know where it was." Oleh said.

He and his friends try to get through hard times with humor, sometimes quite black humor.

"For several years, we had a joke about which of us would die first and which would die last, and in what order we would die. We always had this spooky competition. If someone goes bungee jumping, we say: ‘No, you're going down one unit there, you can't risk it.’ (…) I was always in last place because of my physical condition, the surgery, and everything. And we joked that we could even go to the bookmakers and order that I would definitely be the first to drop off. But when I escaped the war, they were saying: ‘Yours was the last position, and now it may be you are at the top’. My friend, who is 33 years old, we are all 33 years old, we have been friends since high school and… he had a stroke from the war. He said: ‘Guys, I think you should move me to the fourth position’."

Oleh was in a group discussion of men, and he had a discussion with a student from Ukraine, Denys, who was studying in Vienna at the time. And perhaps it was this group that made the biggest impression on me. It allowed me to better understand my husband, who does have a legal opportunity to cross the border, but he chooses not to be with us all the time. The dominant emotion in this discussion was guilt. This topic was raised in almost every group, which was mostly women. But it was here that it was most acute, for obvious reasons. However, I myself often feel guilty. For example, for being safe and comfortable with my children, but still not feeling emotionally balanced. The professional position of one of the participants allowed me to come to terms with this.

Photo: Linda Zahra

Participant Nastia, who was completing her master's degree in psychology remotely at the time, spoke about the continuum of traumas that are impossible to overcome at once:

"Everything we've been through, especially these rapid evacuations and relocations, is stress on top of stress. It won't be PTSD anymore, it will be even worse. It will turn into bigger problems. A person who has survived the fear of war leaves their territory: friends, people, dogs, cats; a long, exhausting journey, without food, without belongings. And when, after that, they find themselves in some trash and are told: ‘You're safe, live!’ (…) Especially when it comes to women who have been displaced, with children, having experienced separation from their husbands. Do you realize the number of traumas there?"

But at the same time, a statement of the same participant became a trigger for me. Before the disсcussion, Nastia noted that the main purpose of her participation was to prove that Ukrainians are not Syrians. In fact, this was hardly discussed during the focus group, but she still noted:

"Ukrainians are a more educated nation. They did not come here to receive subsidies. If I, or anyone else, wanted subsidies, they would have gone to Germany, to those countries that provide this kind of support. But we chose other values, and so to hear that we are the same as Syrians – yes, it touches me. And I am not a Muslim, no."

Several other participants made similar statements.

Before the research started, our Austrian colleagues asked us to be attentive to our own state and stop the discussions if something proved to be traumatic. I thought that I would be touched by stories about the first days of the war or something like that. But the unexpectedly unpleasant moments happened for two reasons: the mentioned attempts of the participants to prove that they were better than refugees from other countries, and when they believed in conspiracy theories or other irrational things. I think this actually says more about me, about my desire to see Ukrainians as "proper" Europeans.

Photo: Linda Zahra

On the other hand, there were participants who had established friendly relations with refugees from other countries. Or for example, Lana from Kyiv, who is a graduate student at a university in Vienna and also participates in migration research, was sure that "the way Ukrainians were received in the beginning should be the minimum that any forced migrant should be received."

No room for error

One of the most dramatic stories during the group discussion was told by Inna, a mother of two twin baby boys. Her story puzzled the participants of the focus group, us as researchers, and our Austrian colleagues.

Inna works in IT and is a single mother. Her own mother helps her raise the children. A week before the war, she wanted to take them all to Georgia, but in the end, she traveled alone.

"I begged and pleaded with my mom to go. But she had never been abroad. She didn't want anything, she said she wouldn't leave. She said she was staying. I had a plane at 7 in the morning. And I tried to persuade her until about 3am (…) In the end, I couldn't convince her."

She explained the fact that the children also stayed with her mother by saying that she would not have been able to look after them due to her workload. The compromise was that her mother left Kyiv for a village closer to the Moldovan border.

While in Georgia, Inna learned about the outbreak of the war and tried to evacuate her family remotely for three days. All this time she did not eat and eventually almost fainted on the plane.

"We had to go to passport control in Bucharest. There were a lot of people there, and I was already on the plane and I felt dizzy. I thought I would probably fall if I stood up. It was the time when I felt I really might not be able to go on. The expectation to meet the family was too exhausting," Inna said.

It seems that she had a strong sense of guilt because she had made a mistake – she had not been assertive enough and left her children in Ukraine. This is one of the paradoxes that we noticed during the research and which we also felt very well. On the one hand, Russian aggression came as a shock to most people. Millions of Ukrainians have become victims, directly or indirectly. However, on a personal level, both individuals and the society, in general, have expectations that you have to grit your teeth, not make mistakes, and survive.

For example, the sisters Kateryna and Tetiana, two young girls from Odesa, told us how they crossed the border with an acquaintance who could not take control over her feelings:

"She was hysterical. She wouldn’t stop crying and saying 'Where are we going, why are we going there', but we still wanted to help her leave because there was no one else to take her. We didn't know where we were going, we just wanted to cross the border and then decide what to do. She later returned to Ukraine."

Photo: Linda Zahra

The need to keep a cool head and make the right decisions, especially if you are responsible for children, was also discussed by Liudmyla, the mother of two teenagers who left Kharkiv.

"And I understand that one needs a hot heart and a cold mind to understand and do the right thing in such conditions, that's it. But emotions – they are somehow silent, dormant. And the only conclusion to make here is that life goes on, no matter what state one is in, frozen, like some petrified Snow Queen. But one still has to go on living and be responsible for one’s children."

Another participant, Maria, who took her three children out of the Kyiv suburbs at the beginning of the war, which suffered the most during the attempt to capture the capital, echoes the same sentiment.

"The moments of leaving the homeland are associated with sadness because of a loss. But for me, this moment is not so scary, as one just mobilizes and thinks about what decision to make. One kind of decision here, another there. Seariously, three children, (a joking tone) and you have to deal with them somehow…"

Who was affected by the "therapeutic effect" of our study? / Does this work have an impact?

Our research has little practical or advocacy agenda in the narrow sense. Rather it is theoretical, aiming to find more "correct", balanced terms for the phenomena generally described as "integration" or “arrival” of the displaced. This research relies on what refugees themselves say about themselves and their experiences. But an unexpected side effect of our discussions was the "therapeutic" effect we as researchers, and definitely some of the participants experienced. It turned out that all of us really missed the opportunity to talk in a safe atmosphere deliberately focusing on what we have been through.

After the discussion, Oleh, who left Ukraine with his elderly parents and disabled brother, wrote to us:

"For one, it is an interesting project, but it also had a therapeutic effect. I have never seriously told anyone about my experience of war-evacuation-adaptation in detail, from the beginning to the end. I even remembered new details along the way."

And Lyudmyla, a mother of two children, the eldest of whom is 16, asked for advice on how to apply for admission to one of the Austrian universities for her daughter. She also thanked us for having met for the discussion:

"I would like to say that after the conversation at the 'Art of Arrival' my moral state improved. probably because I spoke out or lived through the situation and finally let it go. I just realized that there is no point in clinging to the past anymore and that I need to live and act on. Thank you for that."

However, for example, a young girl from Crimea, Anna, who also moved to Vienna recently to study, later noted that "perhaps to feel some relief, I need to talk to someone with the same confused sense of identity as mine." She was the only participant from the long-occupied territories, and the other participants actually knew very little about life in Crimea after the annexation.

So, of course, we can't claim that we were able to solve any psychological problems of our participants in any way. Or even more so, to influence systemic problems, such as the lack of decent work.

But at least for us, this experience allowed us to better understand what is happening, to see the reactions of real people, to find in them a reflection of ourselves and our loved ones. This makes it a little easier to come to terms with the reality.

On the other hand, we also came across a view of events that is not typical for us. This also prompted us to think on the topis of the origin of such views.

Authors: Olena Tkalich, Yelyzaveta Zolotarova

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva