In his public speeches, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev often refers to Armenia’s sovereign territories as “Western Azerbaijan.” After Azerbaijan’s victory in the 2020 war in Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh), the blockade that left 120,000 Armenians cut off from the world, and the fighting in September 2023 that led to Azerbaijan’s full control over the region and the eviction of the Armenian population, Aliyev continues to make new territorial claims against Armenia.

We talked to Azerbaijani photojournalist and reporter Bashir Kitachayev about the possible threat of war, the situation of ethnic minorities in the country, political repression, and the future of Artsakh. Bashir was born in Luhansk, but when he was still a child, his family moved to Azerbaijan. Since 2018, he has been working as a journalist, writing about the consequences of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and human rights in Azerbaijan. In 2021, when repressions in the country began to intensify, Bashir left and has been living in exile ever since.

What was the mood in Azerbaijan when Aliyev started the war in 2020? Did it change after the signing of the peace treaty and Azerbaijan’s actual victory?

In 2020, about a month before the war broke out, there had been clashes on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border. Then protests erupted in Baku. However, people were not demanding that their rights and freedoms be respected, but that hostilities begin. In the fall of 2020, a full-scale war broke out. After the defeat in the First Karabakh War (1992–94) and territorial losses, Azerbaijanis harbored resentment that the Azerbaijani authorities have been actively using to incite hatred between the Azerbaijani and Armenian peoples since the 1990s. A xenophobic ideology took root in the country, which turned it into a fascist state. In fact, that is why Azerbaijanis were so happy about the start of the war.

Most of the population disregarded and continue to disregard the losses. At the time, it seemed to me that people perceived the war as a football match where they cheered for their team. After the so-called “peace” treaty, nothing changed. There were hopes that this would be the end of it, but the propaganda and incitement to war only intensified. However, if earlier it was a thirst for revenge, now it is a desire to conquer as much territory as possible.

At the same time, it seems that the number of disappointed people has increased, because in some circles there was an opinion that the conquest of Karabakh would serve as a step towards the democratization of the country. People expected an improvement in social welfare. However, many people, for whom the criterion of a successful country is the size of its territory, rather than their personal well-being and respect for rights and freedoms, began to demand new victories.

Ilham Aliyev. Photo from public domain

Aliyev gained the image of a strong leader after 2020, with all his trademark “fist-waving” before the camera and threats. Before 2020, when he appeared in public, it would be somewhere where he would usually cut the ribbon, for instance, to open a newly constructed underpass. And now he is the “victorious president” and naturally, he doesn’t want to give up this title. The “mournful” rhetoric of the defeated has been replaced by the rhetoric of the victors: Azerbaijan has its own version of the Putinist slogan “We can do it again!” When Aliyev gained full control of Karabakh, the authorities immediately turned their attention to Armenia. Before, they used to talk about the return of internationally recognized territory, but now they say that Armenia is located on the “historical lands” of Azerbaijan.

For more than 10 months, the Armenian population of Artsakh was under siege due to the blockade by the Azerbaijani authorities of the only road connecting Armenia and Artsakh. In the fall of 2023, during a new military aggression, Azerbaijan took full control of the entire territory of Artsakh, including the capital Stepanakert. What was the role of Russian peacekeepers since their presence in Artsakh? Could they prevent the blockade and the expulsion of the entire Armenian population from Artsakh? Could they have contributed to a peaceful resolution of the conflict?

Russian peacekeepers are among the main culprits behind the blockade and expulsion of the Armenian population. They didn’t meet their obligations. Of course, it is important to recognize that the deployment of Russian peacekeepers postponed the expulsion of Armenians for some time and prevented the massacre of civilians by Azerbaijani troops. Even then, videos and photos of war crimes were already appearing online. Dozens of people were reported missing during the war — most likely, they were simply killed. Russian peacekeepers were deployed in the region for a reason. Russia managed the conflict because the West turned a blind eye to the escalation. Moreover, the Russian peacekeepers had no mandate to use weapons to protect civilians, only to open fire to protect themselves. The Azerbaijani authorities realized that it would be possible to negotiate with them.

After the victory in 2020, Azerbaijani troops began to “probe the ground” by regularly shelling the villages and shooting at farmers to interfere with their work. The population appealed to the peacekeepers for help, but there was no response. A farmer was killed right in front of them while he was working on a tractor, and the peacekeepers didn’t even insist on an investigation. They, together with Azerbaijan, simply helped to “hush up” this case. The Russians themselves made it clear that they would do nothing. At the same time, the Azerbaijani troops began to feel more and more powerful.

The situation became even worse when Aliyev and Putin concluded an alliance agreement, which was signed a few days before Russia’s attack on Ukraine in 2022. They pledged not to take hostile actions against each other, which affected the situation in Karabakh. The Azerbaijanis began to advance their positions deeper into the territory, resort to psychological pressure on the Armenian population, and organize shelling. During the ten months of the blockade, the peacekeepers didn’t try to solve this problem. In their presence, Azerbaijanis set up checkpoints at the entrance to the Lachin Corridor, kidnapped Vagif Khachatryan to fabricate a war crimes case against him. This was all part of a campaign of pressure on Karabakh Armenians to force them to flee. It was expected that Armenians would leave sooner out of fear, but they did not. In the end, the Azerbaijani side resorted to full-fledged military aggression. The peacekeepers failed to meet their obligations to prevent hostilities. Moreover, the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense claimed that it was conducting its operation in close cooperation with the peacekeepers.

A protester with an Armenian flag in front of a checkpoint of Russian peacekeepers on the outskirts of the Nagorno-Karabakh capital Stepanakert, December 24, 2022. Photo: Davit Ghahramanyan / AFP / Scanpix / LETA

There is evidence that the peacekeepers sold food and household goods and transported people for money during the blockade. In other words, they not only failed to meet their obligations, but also profited from the residents exhausted by the blockade. Although there are now no Armenians left in Karabakh, the Russian peacekeepers have not left. Even now they don’t prevent the Azerbaijani authorities from demolishing Armenian cultural monuments and buildings. The peacekeepers played a pivotal role in everything that happened: they allowed it to happen.

Azerbaijani politicians and media often talk about the possibility of peaceful life for Armenians within Azerbaijan. They talk about the protection of the Armenian language and cultural heritage. Does this sound realistic?

There is absolutely no chance that Armenians will live safely in Azerbaijan. The country already has big problems with human rights. If we open any report from a human rights organization, Freedom House, for example, we will see that in the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, a small, unrecognized republic, there was much more freedom than in Azerbaijan. Nagorno-Karabakh was on the list of partially free countries, while Azerbaijan was on the list of unfree, authoritarian countries.

There are no independent courts or media in Azerbaijan, and the police serve the government. There are no elected representatives of the people in state bodies, as elections are regularly rigged, and the country is ruled by clans. Now consider the question: How would you live in such conditions if you belonged to a nationality that has been demonized at the state level for decades and has been the victim of constant incitement to hatred? Armenians living in Azerbaijan would have the same rights as Jews in the Third Reich.

On the international stage, Azerbaijan speaks of peace. Constant military provocations, attacks, kidnappings, hostile rhetoric, xenophobic propaganda, hate speech, and, eventually, a humanitarian blockade — all of this showed that nothing good awaits Armenians in Azerbaijan. How can they talk about preserving language and culture if the Armenian cultural heritage is denied at the state level? According to Azerbaijani myths, all Armenian churches belong to Caucasian Albania. Cultural heritage that can’t be appropriated is destroyed, like that of the khachkars in Julfa, for example. Nowadays, a UNESCO monitoring mission is not allowed to enter Karabakh.

An Armenian family transports a modular house on a truck, November 18, 2020. Photo: Sergei Grits / AP / Scanpix / LETA

Of course, they were lying when they said they would protect cultural heritage. The only thing that was left intact was the Armenian church in Baku, built in the nineteenth century. It is used as a warehouse. It was spared for a specific purpose: to show the world that we have an Armenian church, we didn’t demolish it, so we are preserving the Armenian heritage.

Any attempt to talk about their rights would result for Armenians in arrests, killings, and constant accusations of separatism. Azerbaijan deliberately made life unbearable for Armenians in Karabakh so that they would certainly leave the region and not interfere with Aliyev and his business friends’ efforts to seize territories for personal gain and budget embezzlement.

Aliyev understands perfectly well that if he ends the conflict now and Azerbaijanis stop hating Armenians, the former will hate him. He will be held accountable for why the people of the country don’t benefit from huge oil revenues, why salaries are low, why their standard of living is in some respects lower than that of their neighbors who don’t have oil.

Azerbaijan is home to various ethnic minorities. Among them are Talysh, Lezgins, and Tats. What is their situation?

Members of ethnic minorities can’t study in their own language. There are hours in school that are allocated for language learning, but they are very few. The only ones who have the right to study in their language are Russians and ethnic Georgians. Everyone else studies either in Azerbaijani or Russian. I graduated from a Russian school. Tats can’t even learn their own language at school. Teaching is often done by educators without the relevant qualification: I know of a case when a P.E. teacher taught Lezgin just because he was a native speaker.

In Azerbaijan, you won’t be arrested simply for speaking your native language. But if you are a member of an ethnic minority, you must be loyal to the state, otherwise you will be accused of separatism. In the 1990s, the Talysh and Lezgins demanded autonomy, but their activism was quickly suppressed. In the 1990s, there was a terrorist attack in the Baku Metro, which led to the arrest of members of the Lezgin movement Sadval. They were tortured, and some activists died of torture. The international human rights organization Memorial recognized the members of the Sadval group as political prisoners, as it was proved that their testimony was given under torture.

Victims of a massacre in Baku, January 20, 1990. Photo from public domain

Attempts by national minorities to speak out about their rights — the right to preserve cultural traditions and language — are quickly suppressed and they are accused of separatism. However, such rights are guaranteed by the Constitution of Azerbaijan and several international conventions signed by the Aliyev regime. Ethnic minority activists are arrested or killed under strange circumstances. For example, Fakhraddin Aboszoda was a journalist and prominent figure of the unrecognized Talysh-Mugan Autonomous Republic, which activists attempted to establish in the 1990s. In 2018, at Azerbaijan’s request, Russian security forces arrested him in Russia and handed him over to Azerbaijan, where he was imprisoned for treason. He was sentenced to 16 years and died in prison in 2020. Later, Fakhraddin’s lawyer allegedly committed suicide, saying shortly before his death that the authorities wanted to kill him.

Then there is the case of Novruzali Mammadov, scholar and linguist. Unlike Aboszoda, he was quite loyal to the authorities, he was not a member of the opposition — he was just studying language. After Novruzali traveled to Iran to attend a language conference, he was accused of spying for Iran and given a prison sentence. In prison, Novruzali became ill, but he was not provided with medical care and died.

Opposition media outlets and forces in Azerbaijan are also generally nationalist in their attitudes and don’t cover the problems of ethnic minorities, just as they don’t cover the deaths of activists. Opposition media reported on the trials of Armenian prisoners of war captured during the Karabakh war and didn’t even try to find out whether the accusations of the Azerbaijani side were really justified.

The authorities want you to be an Azerbaijani first, and then a convenient “pet” Lezgin, infinitely loyal to the government and ready to go to war for it at any time. Many activists and journalists from ethnic minorities were forced to leave because they could be persecuted or even killed in Azerbaijan. If a Talysh or a Lezgin hangs their national flag on the balcony, they face a prison sentence, because flags of ethnic minorities are considered separatist symbols.

A peaceful protest in central Yerevan against the Armenian government’s actions to resolve the situation in the Nagorno-Karabakh region, September 20, 2023. Photo: Narek Aleksanyan / EPA / Scanpix / LETA

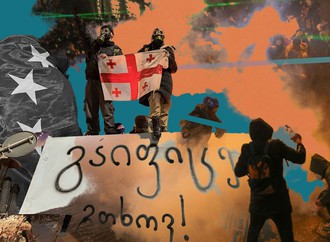

Were there any anti-war protests in Baku?

Most of the population would disapprove such protests. For them, peace is peace on Aliyev’s terms, and anti-war protests are perceived as betrayal. For instance, in 2020, anti-war activists were summoned to the prosecutor’s office “for a conversation.” The police didn’t even take them seriously because people who opposed the war in 2020 were a tiny minority.

Of course, organizing an anti-war protest can be dangerous. Even outside of Azerbaijan, being an activist is quite dangerous. In Azerbaijan, you are always under surveillance. They check the information on your phone: you must register your SIM card code, and so mobile operators can share data at the request of law enforcement, even without a court order.

Recently, Russia handed over to Azerbaijan soldier Kamil Zeynali, who took part in the brutal murder of an Armenian grandfather during the 44-day war in 2020 (the video of the murder is still publicly available). Has the international community reacted to this? How was the perpetrator received in Azerbaijan?

Back in 2020, I saw that video, where an old man is beheaded. I still can’t say for sure whether it’s Kamil Zeynali in the video or not. But he was traveling to the front at the time, making aggressive statements, calling on Azerbaijanis around the world to kill Armenians.

Kamil Zeynali was, of course, not greeted as solemnly as the infamous Ramil Safarov. But a group of government officials and the media arrived, a flag was wrapped around him, and he was welcomed as a hero. It is hardly surprising that Russia extradited him to Azerbaijan. Moreover, the Russian side is offended by Armenia’s accession to the International Criminal Court, which obliges Armenia to arrest Vladimir Putin and all other Russian war criminals on its territory. Under no circumstances would Zeynali be extradited to Armenia for investigation. The international community didn’t react because it doesn’t care; it continues to pretend that there is no xenophobia in Azerbaijan. As a result, Zeynali is now free.

I believe that one of the main steps to end the conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis would be the trial of war criminals, because the main narrative that leads to hostility is the narrative of revenge. After Azerbaijan won the war, the political initiative is on its side. Unfortunately, the Aliyev regime decided to continue the conflict because it guarantees its survival.

In a recent interview, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said that the Azerbaijani authorities are preparing an attack on Armenia. Why does Azerbaijan seek new military aggression?

I also see preparations for aggression. Every day the Azerbaijani media promote the narrative that Armenia is on the historical lands of Azerbaijan — ideological grounds for war are being laid within the country. Aliyev buys weapons and organizes military exercises. He is confident that he will get away with an attack on Armenia because the West is focused on Ukraine. He is also confident that in the event of sanctions, Azerbaijan will withstand the pressure thanks to its ties with Turkey and Russia. Aliyev plans to do the same as Putin, illegally trading gas and oil to circumvent the sanctions.

By the way, in 2022, the European Union began buying gas from Azerbaijan. It was an unprecedented event when President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen came to Azerbaijan and signed a gas contract to increase gas supplies. And the most interesting thing is that she did this without any preconditions: for example, an ultimatum to stop military aggression or to abandon the policy of repression and imprisonment. Russia still receives money for the gas, because Azerbaijan has lately experienced a lack of natural gas for its own consumption and began to buy it from Russia. This is how Europe has “got rid” of dependence on Russian gas.

Armenian soldiers on the contact line in the Lachin corridor, February 2, 2023. Photo: Gilles Bader / Le Pictorium Agency / ZUMA Press / Scanpix / LETA

It turns out that the European Union openly sponsors wars, repression, and human rights violations in Azerbaijan. Because, on the one hand, Azerbaijan is in allied relations with Russia, and on the other, it supplies gas to the European Union and generally has carte blanche to do whatever it wants. Europe didn’t stop Russia’s aggression in time, and we see what it led to. In 2014, Russia was allowed to seize Crimea, and at the same time launched the Nord Stream and gas pipelines. Both Putin and Aliyev perceive the West’s reluctance to escalate as weakness.

In the twenty-first century, an entire nation of 120,000 people was deliberately kept under a humanitarian blockade and starved to death — and Azerbaijan didn’t face any consequences for this. Regular statements were made, there were two decisions from the International Court of Justice and the ECHR — Azerbaijan didn’t care. Just last year, Aliyev openly said at an event in Shusha that signatures and treaties are worthless. All that matters is force — a position that he shares with Putin. Military aggression is also beneficial because Azerbaijan forces Armenia to agree to terms favorable to Azerbaijan. They perceive the Armenian side as the vanquished, deprived of the right to vote or to put forward their own demands. And secondly, again, for Aliyev, the war is an opportunity to divert public attention from domestic problems.

From left to right: Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev (in profile), President of the European Council Charles Michel, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and French President Emmanuel Macron during a five-party meeting in Moldova, June 1, 2023. Photo: Press Service of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia / EPA / Scanpix / LETA

Given that Armenia has decided to freeze its participation in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and has stated that it doesn’t support Russia in its aggression against Ukraine, what action will Russia take this time?

Such steps on the part of Armenia are another potential reason why Azerbaijan could again resort to aggression. I think Russia will “ask” Azerbaijan to attack Armenia again to “punish” it, as it happened in September 2023: the whole operation around Nagorno-Karabakh strangely “coincided” with a sharp deterioration in relations between Moscow and Yerevan. Armenia quite rightly accused Russia of failing to meet its obligations, as the CSTO demonstrated that it was not going to stand up for Armenia. Europe, on the other hand, has only now begun to take an interest in Armenia, in the context of Russia’s expulsion from the region.

Putin may perceive Armenia’s withdrawal from the CSTO and rapprochement with the West as a betrayal. Russia could react by imposing an economic blockade, because Armenia is very dependent on Russia: Russia supplies gas to Armenia, Russia also controls its railways, and Russia makes 90% of the investments in the Armenian economy. For the past three years, Russian propaganda media have been broadcasting only the pro-Azerbaijani side and Azerbaijani narratives. If any media outlets in Azerbaijan broadcast pro-Armenian narratives, they would be immediately closed, and their employees would be arrested. Of course, Russia will use any opportunity to make a coup in Yerevan. They will try to push their candidates in the elections. If Russia imposes economic sanctions on Armenia, it will seriously affect the people of the country.

How do you envision the future in Artsakh? Is there any hope that its Armenian population will return home?

It’s hard to say what will happen in the future. Now Azerbaijanis, refugees who lost their homes during the First Karabakh War, are being settled there. As far as I know, they are given apartments, but not houses with land plots, because land usually belongs to large landowners. Citizens are not allowed to invest, because only the right people with connections to the inner circle of power, the Aliyev family, are allowed to invest. In Karabakh, there is unprecedented embezzlement of public money, because it is a region with no oversight. You can’t come to Karabakh without a permit. The Armenian cultural heritage is being destroyed, and no one is watching.

I can’t see any scenarios in which the Armenian population would be able to return home. Of course, if one day Azerbaijan becomes a democratic state under the rule of law and gets rid of xenophobia, then Armenians will be able to return home. But I don’t believe that Azerbaijan will become a democratic state any time soon. It is an authoritarian, militaristic, aggressive state in which Armenian-phobia is part of the state policy and the basis of the state ideology. Now Armenians must preserve their lives and freedom, values, and history. Unfortunately, the international community has allowed all this to happen. And the most important thing that the Armenian side must do now is prevent a possible new aggression.