Among the many Western Marxists who have attempted to understand and politically define the Soviet Union, Hillel Ticktin is perhaps the most interesting. Unlike many other theorists, whose reflections on the subject were often deductive speculation based on fragmentary data, Ticktin set out to thoroughly analyze the political economy of "real socialism" based on what could be read between the lines of the Soviet press. His conclusion was that the Soviet economy was efficient only as long as there were resources for extensive growth. For the intensive model, it lacked a system of motivation of economic agents: having discarded the capitalist motivation of profit, the USSR never built a socialist system. The planned economy of "real socialism" was a hybrid, programmed to be inefficient.

Ticktin lived a fascinating life as a political activist. Born into a family of Eastern European immigrants in South Africa, he became a Trotskyist activist and was forced to emigrate from the country because of his political activities. After spending several years in the Soviet Union, Ticktin settled in Britain, where most of his intellectual and political career took place. Until 2002, he carried out Marxist Studies at the University of Glasgow. In 1973 Ticktin founded the academic journal Critique, which aimed to study Stalinism. Today the journal is the center of important Marxist debates on broader themes. In an interview with us, he shared episodes that have hitherto passed unnoticed by historians.

How did you grow interested in Marxist politics?

My father was on the Left. By coincidence, when he came from Poland in 1930, he came with a fellow passenger called Burlak. Burlak had been politically active in Estonia. He was a Marxist, almost certainly a member of the Communist party, and he left – obviously, Estonia at that time was in reaction, very right-wing. But he had been active in the previous period, during the civil war. I don’t know whether he had an influence on my father at that point, or my father was already left-wing – but the trip from Europe to Cape Town takes several weeks, they obviously got to know each other. And they remained close associates and friends until Burlak’s death in 1976. In other words, when my father came to South Africa, he was either a Marxist, or on the way becoming a Marxist.

He was very closely associated with Burlak, who then founded a Trotskyist group called Unity Movement. It took part in the riots that took place in 1932. Burlak remained its effective theoretician and crucial leader until his death, although the official leader, acting openly, was someone else. He met Burlak every Friday evening. This person died in 1979. The group was very secret. They went underground in 1939. In other words, my father was an underground left-winger – so much so that he took a view that he shouldn’t indoctrinate his own children. I passed because I was his first child; he often responded spontaneously to my questions, and thus he brought me up left-wing, without intending so or realising fully what he was doing. When he did, he stopped it, and my brothers and sister are not left-wing.

Cape Town, early 1930s

My father even became a president of a synagogue. And when I asked him what on earth he was doing, he said: ‘You don’t know what we are discussing on Saturday afternoons!’ – implying that they discussed revolution. I could not fully believe it, but I guess what he meant was that they were not so right-wing.

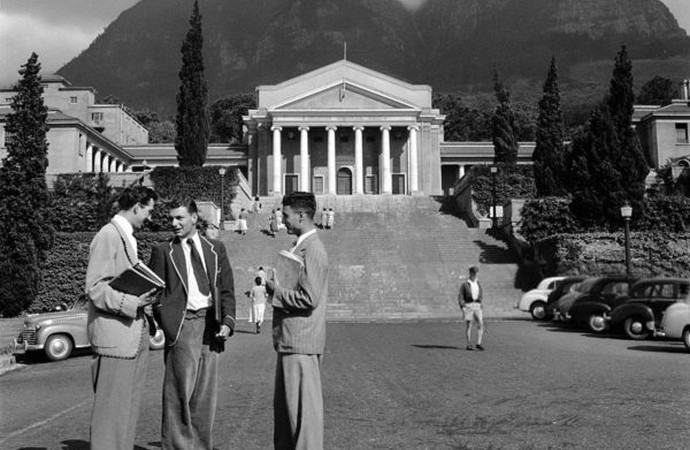

Unity Movement was the biggest Trotskyist group in South Africa, with a substantial following in Cape Town. When I came to Cape Town University, the friends I made there among the so-called coloured students were to a very considerable degree affiliated to this group. One of them eventually became a minister in the first government after 1994, when restrictions on Black people were removed. This was the background in which I was formed.

How influential was Marxism in the university in South Africa back then?

The staff of the university was either right-wing or liberal, there were very few who were left-wing. As it happened, I took courses from Jack Simons, who actually lived not far away from my parents. He was a leader of the Stalinist, Communist Party. He was not an idiot, he did not simply believe the Stalinism that was there, but he preferred to accept it rather than become a Trotskyist. Besides giving university courses, he conducted a study group that I attended. The secret police was of course aware of that – in fact, on one occasion, when I drove away from Jack Simons’ house, I was followed. When I realised it, I went around a roundabout, and the guy followed me; I went around the roundabout ten times before the secret police took off because they were getting giddy.

I also met other people around him, critical of the Communist Party – including one person who was influential in the Communist Party branch in Eastern Cape province. As a result, that branch was much farther on the left.

University of Cape Town, 1955

Jack Simons was the most influential person in the party until 1950, when communist parties were banned. South Africa was unique in passing a law that specifically stated that Trotskyism was banned as much as was Stalinism. The Communist Party then reformed itself, there was an effective coup by the right, and Jack Simons was effectively in the opposition. The Communist Party line, which developed after it had been banned in 1950, was a more right-wing line, listing a number of stages that you need to pass before you could get to socialism. According to the new line, on the first stage you would overthrow apartheid, and the second stage would be socialism. From their point of view, they were overthrowing apartheid and they still were fighting for socialism, except that it was not very clear where the socialism is. The Communist Party was so Stalinist that they even supported the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. The theoretical level of the members was very low.

That was not true of Jack Simons, of course. In the university, he was teaching a course about the nature of unemployment in South Africa, called ‘Native law and administration’. He had a considerable influence, being one of the few people on the left there. Quite a few people I knew took his courses simply because they were more critical of the system.

Have you ever met Harold Wolpe? He was also a member of the Communist Party at that time.

I interacted with Harold Wolpe more than once. The one where I talked or argued with him was in the Bulgarian holiday coast at the International Sociology Conference in 1974. He clearly was a member of the South African Communist Party. I think he had a post at Essex University at the time. In the 1990s we crossed paths at mass meetings in a university context in Cape Town. I spoke at one or perhaps two of the sessions of the lectures given by an organisation set up by his will, in particular in 2004-5. I am not at all clear where he was coming from, other than some kind of utopian version of a Stalinist party.

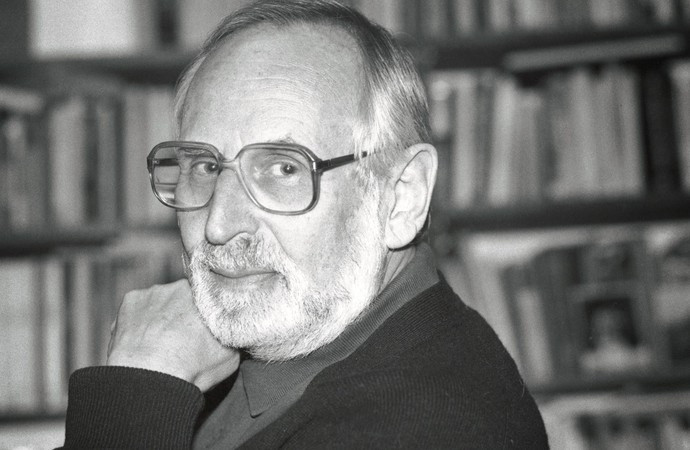

Harold Wolpe

From South Africa, you move to study in the Soviet Union. Why did you decide to do it, and was it easy to get a scholarship in a Soviet university?

The secret police made it very clear that they would do what they could to penalise me. In 1960, I went hanging out left-wing leaflets in a black neighbourhood, which was not allowed. They did not arrest me at the time, but they made it clear that they knew I was there. My father had a deal with them that I would leave the country. Doing it seemed to me better than going to jail. So I left the country. At that time, ANC, which was controlled by the Communist Party, had developed a United Front, and I associated myself with it in London, despite being critical towards the party. There were a number of scholarships given by the Soviet Union at that point, and they recommended me for one.

How would you describe your student life in the Soviet Union? Were you isolated from the wider society, did you have a chance to communicate with people outside the university?

When I came to Moscow, they informed me that they were sending me to Kyiv. This was 1961, Khrushchev was in power. He tried to open up the Soviet Union, and I suppose the invitation to foreign students to come and study was a part of that strategy. It would have had two purposes: one was to forge alliances with the ruling classes of the countries from which the students came, and second, to try and influence the students themselves. But by the time I came, universities in Moscow were full, and people like me were sent to Kyiv – and probably to other places as well.

The students were all put in hostel and given a full-time course in Russian, which lasted from January until September. They put us in contact with local students: each room in the hostel had four people, and they made sure that at least one of them would be Russian as our immediate contact. There was no restriction in meeting anybody. In fact, I met my future wife there. Practically all foreign students found friends, girlfriends.

It was not difficult to talk about politics; being a Trotskyist, I talked fairly clearly with my future wife. Her father had a very responsible post within the Communist Party, she knew quite a lot – and she was very cynical. And I found this was true for everybody whom I could penetrate as to what they were actually thinking. My impression today is that the majority of the population was highly critical of the system, but they knew it was an offence to say so. And they did not know what the alternative was – or were not convinced that the alternatives would be any better. In any case, they knew that if you speak out you can be reported to the secret police. If there were three people talking, there was a chance that one of them would report you or would belong to the secret police himself. I did not know that detail before I came – even though I was critical of the system.

Did you have any contacts with dissident Marxists in the Soviet Union?

I didn’t find any genuine Marxist there. They may have been repeating the official lines without believing in them. But I have not met any Marxist in the Soviet Union. There were some people more or less openly critical and still tolerated to the extent that they were not jailed – they were anarchists. And that was the case when the Soviet Union came to an end: if you look at the voting in the Moscow city council, you will find anarchists among the opposition. But Marxists – I don’t believe it.

In Kyiv, I studied Russian, and then I went to write my thesis comparing the racial discrimination in South Africa and in the South of the United States. I was put in the Moscow University’s department of political economy. In other words, the main Marxist theoretical department of the Soviet Union. They knew very well that they were not teaching Marxism really, but they realised they could not go beyond where they were. The department had tried to move the theory somewhat, but it was a specific way to interpret Marxism so that it justifies the Soviet Union.

So, you only studied language in Kyiv, and your actual academic studies took place in Moscow?

I had a supervisor who did not actually supervise me. He warned me that if I wrote anything critical of the Soviet Union, past or present, he would ignore me. And he ignored me. When I did write the thesis, they refused to accept it, because it was critical of the Soviet Union.

Was there anyone among your Soviet teachers or colleagues who did influence you in some way?

If you leave out the question of Marxism, you could be impressed by the way in which they were trying to adapt. They were not idiots, they knew very well that the system was not Marxist, was not internationalist – to a large degree it was Russian nationalist. My supervisor, Dragilev, had been in fact removed from his post in the 1930s and had to work as a barber. He was very lucky he survived. He happened to be Jewish, and I don’t know maybe they assigned him to me because I was Jewish, too.

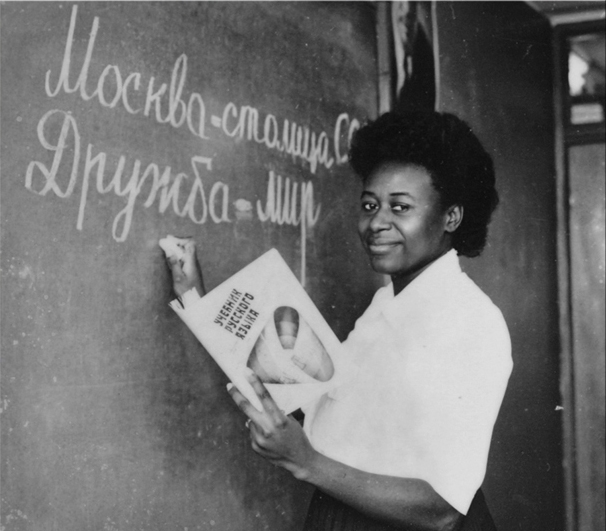

When you were studying the language in Kyiv, you took part in an anti-racist street demonstration by Black students. This event is absent from the post-Soviet historiography. The private diary of the head of Ukrainian Communist Party for 1961 mentions the main events: the major landslide that took many lives, the launch of man into outer space, the staged protest against the US policies regarding Cuba, but nothing about that protest. Can you explain its background?

Black students in Kyiv came from Africa – Ghana, the French-speaking African countries, Egypt, Nigeria – but also from Cuba. They had formed some kind of interaction among themselves. Generally, the Ghanaian students took the lead. The Cuban students took to themselves. The main issue that led to the protest had to do with Black students going out with Ukrainian women.

One night, a student from the French Africa was jailed and then let out at 4 o’clock in the morning. It transpired that there had been a fight in the centre of Kyiv, and it was about the girlfriend that he had asked out. Her boyfriend, or previous boyfriend, or someone whom she knew, took offence that she was going out with a Black person. When they came out, he stopped the student, and a fight took place. A crowd gathered around them, the police came, arrested him and jailed him. When the police reached out to the dean of the university, they realised this might lead to a trouble and let him out.

Students had been talking of the tendency towards racism in Kyiv even before that incident. Subsequently, it was made pretty clear that there was indeed a degree of racism. It was endemic and probably existed within the Central Committee itself. Given that the Soviet Union itself had nothing to do with socialism, there was nothing surprising about it. The chap who stopped the student was a straightforward racist. These students, who felt this attitude, were political. They called for a meeting to discuss this question. The dean accorded a meeting, there were state representatives there. But they were unable to step forward and say: “Yes, we have racism, and we don’t like it. We have to stop it, and we apologise”. They could not say that, and the students got more and more angry. They called various meetings to discuss it, and eventually called for a demonstration very soon, on the next day or the day after.

There was quite a lot of students at that demonstration – maybe all foreign students apart from Cubans. We all met in the centre of Kyiv and marched to the government building, or the Central Committee building. We were all admitted inside, and they asked for representatives. One of the organisers picked six representatives, including me. So I went up with the other five. We took a lift to the floor where we met the secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, and the second person was either the chairman or the vice chairman of the Ukrainian government. Both of these people later became very important: the secretary of the Ukrainian party later became one of the main officials in the whole Soviet Union. The person from the government took the chair and asked the students to speak. The representative of the university was also present, he said: I listened to both sides, and one might think that both are right, but on the whole I agree with students. It was a deliberate attempt to play the whole thing down.

I did not speak, because it was absolutely obvious that if I spoke and said what I have said just now, they would think that I played a crucial role in it, or organised it. So when the secretary of the party asked me to say something, I just indicated that I supported the other students. My future wife spoke to me after that: her father, who was high up in the party, told her that the dean of the faculty said I was a very cunning fellow! In other words, they did think I played a central role in the demonstration, which was not true: if I had not been there, it would have still taken place.

After that, all students were sent to a camp – not a punishment camp, but a resort – where there were lots of girls. And basically that was it. I don’t think anyone was punished for it.

While you were in the Soviet Union, the other Trotskyist born in South Africa, Ted Grant, was active in the UK. His tendency, Militant, was later quite present in labour politics in the Soviet Union and in independent Ukraine. On the other hand, SWP remains probably the largest non-Stalinist political organisation in the Anglophone radical left politics. Between these post-Trotskyist groups and the social-democratic tendencies embodied by the likes of Jeremy Corbyn, where would you position yourself on the map of today’s Anglo-American left?

I actually belonged to SWP between 1970 and 1971. And I could not stand it. Obviously, I am a form of Trotskyist. I don’t think that everything Trotsky did was correct, and I think that in his last period he ought to have gone further. I am critical of people who take Trotsky’s every word as being of itself correct, but in general I am a Trotskyist.

The first group you mention, Militant, is a reformist grouping. At all times I argued with them. I don’t think they realised the nature of the Soviet Union at all. Or what a society today, which went that way, would be like. They just haven’t got a clue.

Ted Grant

The problem with SWP is that they are undemocratic. They are afraid that if they allow a free discussion between the factions they will break up. Which they probably would. The SWP is really a dictatorial organisation over its own members.

I think it is very unfortunate that we have been unable to form a genuine left-wing grouping which can tolerate different views and be genuinely democratic. It may be very difficult to do it, and maybe it is true that the secret police would do its best to make sure it breaks up. But given time, I am sure that a genuine Trotskyist organisation will come into being.

Do you consider yourself close to the Marxist humanist tendency?

No. I haven’t had any discussion with them for many years. I don’t think much of the argument of their founder, Raya Dunayevskaya. Take the example of the falling rate of profit. From the third volume of Capital, it does not follow that it is crucially operative at all times. People who simply base themselves on the falling rate of profit are dogmatists, not theorists. I don’t argue it doesn’t exist, but it’s not always crucial.

It is just a very unfortunate stage, and we ought to analyse it: why at the present time, since the Revolution of 1917, there is no strong Marxist group? Existing analysis of where we are is of itself limited. The groups are repeating what was said in the 1920s, not analysing what has happened subsequently or what was likely to happen. It is taking a very long time for the setback, which the Soviet Union was itself, to be understood, and for people to recover from that. In the countries dominated by Stalinism, the proportion of people supporting Marxism is very limited, as it is likely to be. Clearly, we need a movement able to incorporate that into the understanding of what could happen under current circumstances – while continuing to demand for a genuine socialism.

Many of the existing groups are actually appalling. There are still many Stalinist groups, especially in the UK. A number of Trotskyist groups are so dogmatic that one can only be ashamed of them.

You have famously described the Soviet economy as producing waste and inefficiencies. Today, there are many works criticising capitalism along the same rhetorical lines: highlighting its wastefulness, irrationality and inefficiency. What are the differences and similarities between the two irrationalities?

It depends on one’s definition of waste. Capitalism produces a lot of items that it needs to maintain itself. This production is wasteful and probably harmful for humanity. In the Soviet Union, the real level of production was so low that the question of waste is somewhat different. One part of that is the enormous amount spent on armaments – but this is also true of the capitalist US. Nonetheless, the overproduction of producer goods was another part of what was waste in the Soviet Union. It required considerably more man-hours and resources than it would under capitalism and than it should be required in the socialist society. When people don’t like what they are doing, they will do as little as they possibly can. Especially if you don’t have an incentive system – in the Soviet Union it hardly existed for the direct producers. Hence, they worked as little as possible and as badly as possible within the rules. As a consequence, you needed more people controlling and watching them – a complex structure that itself became costly.

Russia today is an inheritor of this: its productivity is among the lowest in the world. South Africa and Russia. Without a genuine incentive system you can’t build a new society. But you can’t have an incentive system unless the population supports the mode of production itself. If people are not getting what they want out of it, and have no hope of getting it, the system cannot work and it will come to an end, as the Soviet Union effectively did. The idea that it could have gone on is a joke: it had to reform and become something entirely different.

You cannot work as a socialist society until you have preconditions for it. The Soviet Union was trapped in this problem at a very early period and did not survive.

So, in your opinion, the inefficiency of capitalism and its incompatibility with the environment is of different nature?

I agree that capitalism is inefficient. But it is inefficient in a different way. It has an ability to incentivise a different result. Whether it would succeed depends on what you regard as success.

Capitalism can’t do what a socialist society could do: incentivising the population and getting scientists to work out the best way out of the climate problem and following it. Because socialism doesn’t have a profit motive, and it would accept massive economic losses in order to diminish the growth of global temperatures so that people can survive. The problem is the inefficiency of capitalism itself and the profit motive, too. In any case, the way to get to the desired point would be subsidising on a massive scale – how can they do it? I think they will be forced to do it, but it will mean considerable sacrifices for large parts of the population, and even worse than that. I would expect the world to survive, but parts of it will be scorched unless people shift into the socialist direction.

Do you accept any of the currently existing definitions of the Soviet system? Trotskyists would speak of a degenerated workers’ state or of bureaucratic collectivism, whereas most academics simply call it state socialism.

It was obviously not socialist in any sense – so obviously I reject state socialism, bureaucratic socialism or any of those terms. I actually don’t have a term for it. It is certainly bureaucratic, but it does not explain everything. A failed transitional form, if you want?

Is it a replicable historical experience at all?

If we are not re-running the conditions that existed in the past, that is if we are not going back in time, the answer is no. The world is very different today from what it was a hundred years ago. The economy of the 1900s is very different from the economy today. Society is much more socially run, even if it is still in the hands of the ruling class. There is no choice for the capitalist class but to have various social forms. It is no accident that the Prime Minister of Britain is undoing the actions of previous conservative governments and believes in increasing state action.

The society has changed, and it is going along the lines that you might expect, if you are standing in 1917 and wondering what will happen. Then you could work out that there would be a transition period during which the society itself changes. China is entirely different now. It is true that much of the progress there took place in the last twenty years, but if the preceding period had not come into existence, they would not have built what they have today. However critical we are of China – it’s undemocratic, it has the problems of inefficiency that go with the so-called Stalinist-type systems. Consequently, we see that, as it were, in spite of humanity, the society is developing. It’s clear that total production in the world is much greater, the productivity has gone up, and even though many people have a very low standard of living, the proportion of the starving is different from what it was 50 or 100 years ago. We are talking about a movement that has to happen unless the society has to die.

I think the present form, installed by the ruling classes in 1980, has come to an end. It’s clear that Thatcher-Reagan period has failed. The ruling class has to face the question, where do we go now? They are not likely to simply give up and jump into the ocean – they will try to maintain themselves, and the society will continue to develop. The capitalist form, which was already in considerable trouble, hasn’t been able to develop into a new form. And the Left has to recoup itself, try and form an entity which is able to appeal to the majority of the population, instead of appearing always hopeless or incapable. Because the ruling class has no alternative now.

It will start making concessions, and I think this is what is already happening in the US, with the opposition from other factions of the ruling class. And over a comparatively small time, although I probably won’t be alive by then, we will begin to see the formation of genuine workers’ socialist parties.

Do you think the adjective “Stalinist” or “post-Stalinist” is still fitting to the description of the so-called post-socialist economies?

I presume you are talking about China. It clearly isn’t socialist. The form its economy has taken is towards private capital. 60-80% of its industry is private. We can only describe it as some form of capitalism. But it is not wholly that, because the Communist Party still has a measure of rule. What that means exactly, I don’t know. The party leadership takes a more critical stance towards private capital, while at the same time maintaining it and expanding over the world.

Some people would argue that rulers of China have some socialist intent, but it’s very hard to see that. If we follow their description of the world and description of themselves, it is largely Stalinist. I don’t know where the rulers of China are actually going or whether they know what they are doing. But they are very much part of the capitalist economy now. On the other hand, there is no doubt of the importance of the Communist Party within the economy and of the banks being controlled by the state, playing itself a crucial role. I think it is some kind of intermediate form.

The world today is generally in a transitional period, but not the one where there is a force driving society towards socialism. Instead, it is a transitional period going through different crises, while at the same time trying to deal with a pull towards socialism.

In your previous articles, you wrote that there has been no transition towards a capitalist economy in the post-Soviet countries. Describing Russia, you called its political economy a mixture of Stalinism and market economy. How do you see the post-Soviet development today?

The former Soviet Union sank further than I expected. Russia’s primary production is oil, it lost all of its industry. One can’t even talk about it in transition terms. It would have to rebuild before it can have any transition to anything. Of course, it remains transitional in the sense that it is not a successful capitalist power. If it did not hold the atomic bombs that it does, its power would be much less. It is not growing, it is going absolutely nowhere; if it’s going anywhere, it is going backwards. I’m not certain that it can remain as it is for too long. If the demand for oil falls, and the production stops, Russia is going to be in tremendous trouble, and this is where the world is going. I read that 84% of the population want to go back to the Soviet Union – that’s not surprising, but it says something about what exists. It is a limited market form, but it is a backward form that is clearly not going anywhere. It is going to be irrelevant in the development of the world now, maybe play a minor role in certain respects.

In the meantime, Russian elites have certain strong claims concerning their share in the global economy and their military and political influence. Would you say that Russia failed to become a successful capitalist country but is becoming a successful competitor within the framework of military inter-imperialist struggle?

That’s true: the capitalist class in Russia is attempting to maintain itself in the terms that you mention. But in the years 2000-2001, the West made it absolutely clear that it would not admit Russia onto the global market, and they haven’t. If they allowed Russian capital to develop in the way American capital has expanded internationally, that would be different, but it is completely cut off. Now these states want to act in the same way towards China, and we’ll see what happens.

The crucial question is what happens in the United States. If Biden’s demands for a series of trillion-dollar-scale expenditures are met, the US will have developed into a social-democratic direction, which will change the form in which it is actually developing, and open new possibilities. But this development can be fully or partially blocked. In that case, there is a possibility that the far right will take power in America, which will alter the direction of the world.