Mykhailo Amosov

For almost 30 years, the question of land reform has occupied Ukrainians. Currently, this stalemate seems irreversible. This article considers what has been happening with regards to the ‘land question’ over the past 30 years, where we stand today, and what to expect in the future.

Land during Soviet times

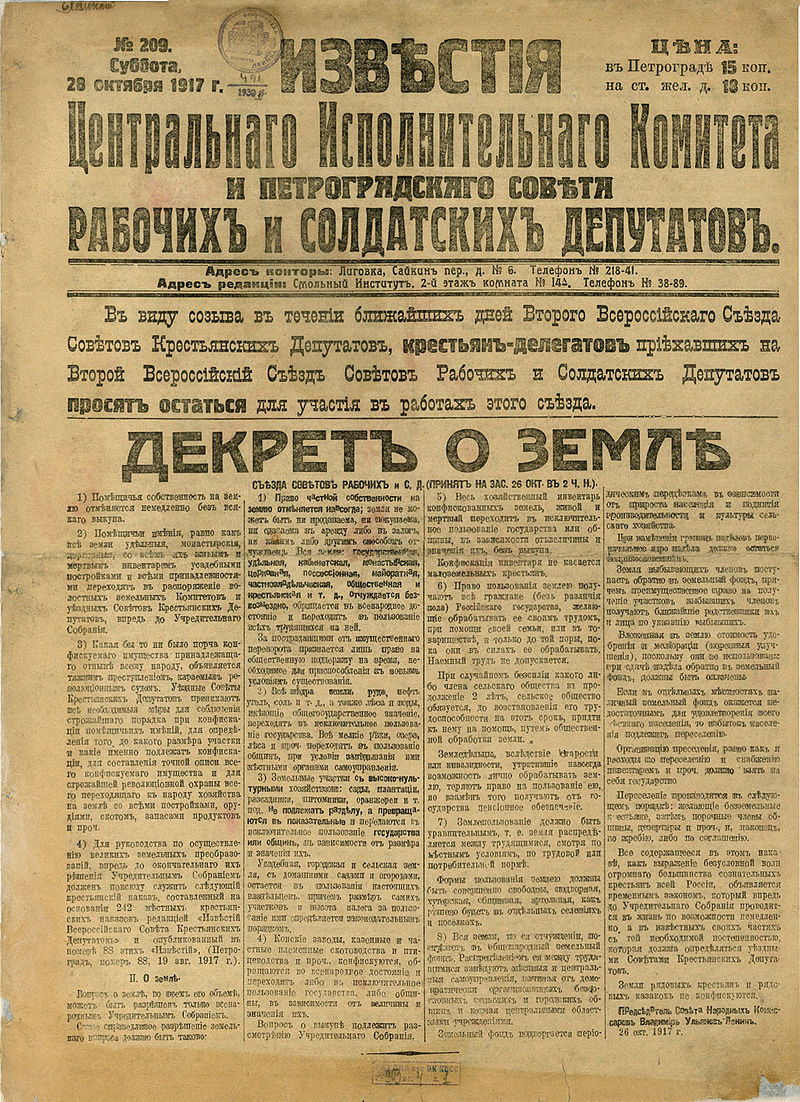

From 1921 until 1991, Ukraine was part of the world’s largest country, the Soviet Union. Right from its assumption of power in 1917, the Bolsheviks issued a Decree on land. Substantially, the Decree provided for the socialization of land and its widespread use by working people with land passing into the hands of peasants. Expropriation of land from landlords took place without any compensation. The Decree further prohibited any type of land market transaction.

With this decision, the Bolsheviks attained popular support in Ukraine since land issues have always been pre-eminent in society. This allowed the state to accumulate decision-making power over land allocation and use. New land and farming structures emerged, including (since 1930) state farms (Sovkhoz) – entirely state-owned enterprises – and collective farms (kolkhoz) – nominally voluntary associations of citizens with collective property, including land.

Decree on Land

Gaining independence and launching the reform

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine gained independence in 1991. This marked the beginning of the tranistion during the 1990s towards a market economy and a series of neoliberal economic reforms. This included, as one of the principal reforms, the strenghtenenig of rules and regulations around private property. Land became a key target since the country’s land structure, formed during Soviet times, allowed only for forms of state property.

A pro-market land reform programme was launched with the issuing of the Land Code in 1992. Its approval by the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian parliament) enabled the partition and privatization of land within the agro-based enterprises.The initial stage of reforming land relations invovled the privatisation of the former state-owned farms (sovgosp). A second step included transfering land to the collective ownership of the agricultural enterprises. The land was delivered on condition that it might be divided on the demand of the enterprise shareholders and, if necessary, allocated as private property.

Foto: Majda Smalova

This led to the emergence of so-called collective agricultural enterprises (CAEs) which became key actors in the privatisation process. Land transferred to the collective ownership of non-state agricultural enterprises ought to be shared, with members of the enterprises obtainaining state certificates guaranteeing their right to a particular plot of land. The certificate holders achieved the right to withdraw from the enterprise and receive their private land shares. In some parts of the country, there was prior experience of such proof-of-ownership documents (for example, in Sumy and Zhytomyr regions).By the end of 1999, the initial stage of the land reform was largely complete. More than 6 million rural people had received certificates confirming their right to obtain private land shares.

A new stage of the land reform began at the end of 1999 with the openening up of the previously established CAEs. While the CAEs were in essence a form of agrarian entrepreneurship, liberal minded reformers believed them to be still too similar to former Communist structures, hindering the development of a free land market. International financial institutions such as the IMF actively monitored and advised the Ukrainian government on privatization processes during this time. As a result, further privatisation measures were introduced and accelerated. Shareholders started receiving their land shares from the reformed CAEs and legal formalization of the state certificates on land ownership was actively undertaken. Parcellation – the division of land into discrete private land plots – was carried out until the end of the 2000s. Registration of land shares in the State Land Cadastre is still ongoing.

The moratorium comes into force

The adoption of the new edition of Ukraine’s Land Code (LCU) in October 2001 gave a new impetus to the reform of land relations.

It has consolidated the key principles of the land reform:

-

the expansion of private ownership of land;

-

state's guarantee of land rights to legal entities and citizens;

-

division of state and communal lands;

-

increasing the economic potential of the land in human settlements;

-

introduction of state management of land resources and land use on the basis of economic evaluations

-

improvement of the calculation of the rental rate

-

the development of lease relations.

Foto: Niels Ackerman

Critically, this Land Code introduced a number of restrictions on operation of the land market. One such restriction was a moratorium on the sale of agricultural land.

The moratorium includes a ban on the sale of land for farming and other agricultural commodity production, including through the transfer of land shares allocated to citizens during the land reform process. It is forbidden to sell land, change the intended purpose, transfer land to the assets of any business enterprises, or to transfer it as a pledge. The only convenient and legal land transfer options include lease agreements and forms of inheritance.

Government representatives claimed that the moratorium was established as an interim measure, with follow up legislation aimed at developing a land market with "adequate" prices to be adopted at a later date. Amongst certain political and societal actors, fears existed that full-scale land privatisation would open the door for the accumulation of land by large private interests, to the detriment of the majority of Ukraine’s farming and rural population. For example, an MP from the People's Movement of Ukraine, Valeriy Asadchev, argued against full privatisation, commenting that, “We cannot allow a dozen latifundists to be formed in Ukraine, and for the entire nation to become farm servants”. It was agreed that the moratorium would be repealed on January 1, 2005 giving everyone time to prepare for the launch of the land market.

However, it is now 2019 and the moratorum still stands, having been prolonged ten times. The moratorium has been extended under a number of reasons or pretexts. Before it could be repealed a state land cadaste needed to be first established then digitized, a state land bank needed to be created, and a law on the turnover of land needed to be drafted, approved, and passed into law. Each of these processes has taken longer than expected while no new draft law has been presented.

Based on information from the State Service of Ukraine for Geodesy (Surveyance), Cartography, and Cadastre (StateGeoCadastre) (2017), 41 million hectares of agricultural land are subject to a moratorium, of which 27.7 million hectares (68%) consist of citizens’ private plots of land. There are 10.5 million hectares of state and communal land that are subject to the moratorium.

A land lease loophole

Even though the moratorium was intended to prevent land concentration, the reality has turned out quite different. In fact, although the formal sale of land has been prohibited, the period since the introduction of the moratorium has seen some of the most dramatic increases in the concentration of effective control of agricultural land in the country’s history. How has this happened?

After the moratorium was introduced, land lease has become the main (although not the only) way to control land in Ukraine. Immediately after the privatization of land, a huge land market has been formed which, due to the huge offer of land plots, cost very little to rent. Millions of owners were ready to rent their land for trifling sum as a lack of capital and spatial inaccessibility (the plot is often located 5-10 km from the house) impede many farmers from cultivating their plot of land by themselves. In 2016, the average cost of renting 1 hectare is about €40 in Ukraine, compared to €151 in Hungary, €226 in Bulgaria, reacing up to €791 in the Netherlands. As a result, companies have found legal means to circumvent the prohibition on land sales. Gradually, hundreds of small plots (on average 4 hectares) have concentrated under their control through lease agreements. The state is also actively involved in the leasing of agricultral land by conducting public land auctions.

Foto: Niels Ackerman

The use of these lease agreements was made even more attractive through the successful lobbying of business to amend Ukraine’s Civil Code in 2007. This amendment provided lease holders with a much wider range of opportunities, such as the use of especially long-term lease arragements known as emphyteusis.This particular type of contract was created more than two thousand years ago in ancient Rome during the times of slavery. It involves the right to full benefit and use of agricultural land for a long period of time and in many aspects, resembles full ownership even if technially speaking still a leasehold.

Emphyteusis constucts did not become immediately popular among investors but as the moratorium was prolonged, companies began offering peasants and other landowners long-term lease contracts for a maximum term of 49 years (with even an opportunity to launch an indefinite emphyteusis). In this way, emphyteusis became a sort of agroholdings’ panacea for the moratorium. Between the third quarter of 2015 and the second quarter of 2017, about 28,000 such contracts were concluded, comprising about 80,000 hectares of land in Ukraine.

Does the moratorium help or hurt the rural population?

The number of emphyteusis contracts is increasing and the Ukrainian NGO EcoAction considers it necessary to raise awareness about the advantages, disadvantages, and risks of such lease agreements amongst Ukraine’s rural communities.

Some of the risks are inherent to the nature of such an exceptional contract type as eumphyteusis which are open to potential abuse. For instance, reselling the right to use without the owners’ consent, inheritance issues, and the impossibility of annulling of such a contract.

Photo: Niels Ackerman

Beyond these procedural points, there are other risks related to the future of farming livelihoods and the development of healthy agrarian structures in Ukraine, particularly in the context of highly unequal power relations. As land leases have become the main way of conducting business in the countryside, lease agreements are subject to significant competitive pressures, for example through agroholdings (large-scale farming enterprises with at least ten thousand hectares of land under management) who compete with small independent farmers on the rental market. Agroholdings can afford higher rental rates which, in a growing rental market with rising prices, gives them significant advantage. As a result, farmers may lose part or all of their land, forcing them to give up farming and seek alternative employment elsewhere. Corporate competition can also be fierce, as larger firms vie to acquire a weaker company or take a part of its land.

Often agroholdings and other powerful investors are able to take advantage of close political connections and easier access to financing to gain access to and control over land. They have secured the support of cheap loans from international financial institutions such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB), the World Bank, and the Ukrainian government. Thanks to approvals from the Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine, companies with stable financial support have started to buy up agricultural enterprises with leased land and other assets. A larger area of controlled land has become a symbol of success in the agrarian sector – often based on the assertion that enterprises with tens of thousands of hectares of land under their control are more profitable than small enterprises, and that (outside) investors prefer large-scale companies.

These discussions often overlook how powerful actors can tip the balance in their favour. It is difficult, for example, not to notice the impact of agroholdings on Ukraine's national agrarian policy. They successfully lobby for their interests through "their own" MPs in the Verkhovna Rada and through committees that make the necessary amendments to the budget (for example on VAT refunds to exporters of agricultural products and on subsidies to chicken companies). At the local level, elected community leaders are often former agroholding employees, or actively support them as "the only local investor". Since the introduction of the moratorium, dozens of agroholdings and other agricultural companies with large land banks (of dozens and hundreds of thousands of leased hectares) and a strong influence on politics have gradually appeared. This raises concerns about the prospects for democratic land control, especially within the context of the ongoing global land rush.

Photo: Niels Ackerman

Positioning around the land moratorium

Different actos are staking out different positions with respect to the lifting or prolongation of the moratorium while some parties seek to avoid expressing their particular opinon. For example, some agroholdings avoid being clear and direct so as not to frighten their tens of thousands of smallhoders who may worry that the agroholdings would the come out to sweepingly buy up their lands.

Фото: Niels Ackerman

Here are some of the key parties in the debate:

- Agroholdings: Some support the full introduction of a land sales market, some not, and some have not yet expressed their position publicly;

- International and national financial institutions, including investment funds, and development banks. As a rule these actors see great potential in introducing a land market. They are ready to make investments, and are already preparing possible financing options for acquiring agricultural land;

- Political parties. These often speculate and manipulate their electorate, who are sensitive to the land issue, but in practice they mainly support the interests of large-scale agricultural enterprises;

- Public organizations, including non-governmental organisations. Often influenced by agribusinesses or MPs these actors rarely take an independent position on the moratorium;

- The authorities (current government and regulators). The current authorities aim to be diplomatic with all of the above-mentioned parties. In fact, the authorities seem to stand in practice with those agroholdings who want to slow down the lifting of the moratorium, while nonetheless depending on international financial institutions.

The most recent strong public statement by a significant stakeholders’ group on the moratorium was the Memorandum issued in 2018 between a number of NGOs, business associations, and investment funds. They argue that the moratorium is an impediment to the country's agricultural investments and a reason for a significant rural decline – although the latest deal between SALIC (Saudi Agricultural and Livestock Investment Company) and the agroholding Mriya, amongst others, shows that investment is in fact taking place.

Strikingly, for 18 years, smallholders and other individual land owners have not united under the umbrella of a similar memorandum. Why? After talking with dozens of people in Ivano-Frankivsk region, Vinnytsia region, and Cherkasy region, the author has made the surprising discovery that the locals are not even aware of the moratorium on the sale of agricultural land. The community members interviewed were convinced that sales are in fact taking place, through emphyteusis or gift contracts.

Beyond the moratorium: on the way to democratic land relations

While the future of the moratorium remains contested, it is likely that it will be repealed in the future. It has not fulfilled its role in preventing land concentration as initially expected and it may have even enabled further concentration as companies do not need to officially own land to gain control over it The European Court of Human Rights has also found that the moratorium violates private property rights.

Lifting the moratorium in the near future might lead to a new redistribution of resources or, conversely, to strengthening the existing alignment of forces of Ukraine’s agribusiness. For this reason, one should think carefully about future land regulations, especially for protecting peasants’ rights and preventing further land concentration. The necessary law on agricultural land sales should become a versatile tool for regulating land sales and harmonizing land relations. It must ensure democratic access to land, especially for marginalized groups, like today’s peasants and smallholder farmers.

As a point of departure, international best practices in land tenure such as the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (hereinafter VGGT) should be taken into consideration.

Currently, we cannot say how effectively Ukraine’s Ministry of Agrarian Policy uses the VGGT during the drafting of a bill on the land market in order to prevent human rights violations, land speculation, etc. Previous experience of implementing the VGGT in some Ukrainian legislative acts reflects the fact that they are underemphasized.

As Ukraine moves forward to consider its future land policy, the debate should not simply be restricted to the lifting or extension of the moratorium. It would be advisable for the government, in drafting the new policy, to examine the conditions which led to the concentration of control under the current regime. In particular, the land policy should take steps to address the constraints which have kept people from cultivating their own land, the pressures which them to sell long-term leases on their land, and what strategies and policies could be put in place to allow people to develop sustainable livelihoods on their land, from seed funding for young farmers, to infrastructural development to allow small-scale producers better access to markets.

Agricultural land use must prioritise food production above other forms of land use, such as construction of (bio)energy complexes. Finally, given the devastating impact on the environment of the model and scale of production employed by many agroholdings – including the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, monocultures GMOs and heavy machinery which have led to soil degradation, loss of fertility, erosion, and a reduction in biodiversity – land regulations must be complemented by environmental laws that protect the environment from irresponsible agricultural production.

The form of cancellation of the moratorium and any future land policy depends on the political will of the future government, formed as a result of the new electoral cycle in 2019. It will also depend on the degree of public involvement in the drafting of a land market bill. We have witnessed the ineffectiveness of the ban on land sales. That is why the approach to regulating land transactions in the future must be more responsible. Land is a vital resource and part of the ecosystem which seriously affects the development of society, especially in rural areas where people are still inextricably linked to the land and its multiple values.