The Russian onslaught against Ukraine has dragged on for over six weeks, costing untold lives and throwing the entire region into chaos. In recent days, the horrific images emerging from Bucha and other areas under Russian occupation have raised further questions about what Putin’s war aims really are and how much suffering he is willing to inflict to achieve them.

As sanctions mount and negotiations drag on with no agreement in sight, how can the killing be brought to a halt? Oksana Dutchak of the Center for Social and Labour Research in Kyiv, who recently fled the country, spoke with the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Fabian Wizotsky about the situation in Ukraine and the increasingly dim prospects for peace.

Oksana, you left Ukraine a few days ago. How was the situation when you left and what kind of information are you getting from relatives and comrades who are still there?

It’s already been two weeks since I left, so my information about the situation on the ground comes from news, relatives, and friends. In general it has become simultaneously more predictable and more disastrous.

The Russian army retreated from Kyiv and Chernihiv regions in the north of the country. That’s where the horrific images of destroyed buildings and infrastructure, massacres of civilians, torture, rape, and kidnappings are coming from. People I know and trust have visited these sites and taken testimony from locals who survived — I say that in case anyone reading this has doubts about what happened there being “Western propaganda”.

Residents of the suburb of Kyiv are evacuated with the help of the military on the destroyed bridge across the Irpin' river

In the south we have the territories occupied from the very beginning of the war. There has been less destruction, but numerous reports of kidnapping, torture, killings, and rape. Local authorities, activists, volunteers, journalists, teachers, and many others are under threat. There is also a growing danger of a Russian offensive there, which could mean a territorial extension of the occupation and, hence, of more brutal repression and violence.

The worst situation will probably escalate now on the eastern front, where the main offensive will take place. We can’t even imagine how many civilians have been killed there and how many went through unspeakable violence. On 8 of April the railway station in Kramatorsk — the main hub to evacuate people to Western Ukraine — was shelled with cluster bombs. Dozens were killed.

Russia will do its best to hold these territories while capturing more, concealing the casualties and destroying evidence of its crimes against humanity. On top of all this are the constant airstrikes behind the frontlines, which target critical and military infrastructure even as far as towns and villages in Western Ukraine.

Nowhere is safe now. Of course, the level of “personal” safety varies depending on where one is located. But after Russian officials openly declared their genocidal intentions recently, we have come to understand that the existence of Ukrainian society as a whole is under threat. It appears that they think basically any crime, destruction, repression, or level of violence is justified now. At this point, only a change in the material conditions can stop them.

What do you mean by “material conditions”? And what does the Ukrainian Left want from their comrades abroad, but also from Ukraine’s Western partners?

What I mean is that only material conditions will change Russia’s behaviour— and by that I also mean forcing them into meaningful negotiations. Roughly speaking, the material conditions can be classified as military and economic.

The military dimension, of course, is about the battlefield. This dictates directly how much Ukrainian territory will be under Russian occupation in the immediate future, and hence defines the scope of violence and destruction in the short term. The economic dimension is about sanctions, which will determine, in the middle and long term, what kind of resources Russia has to supply the war.

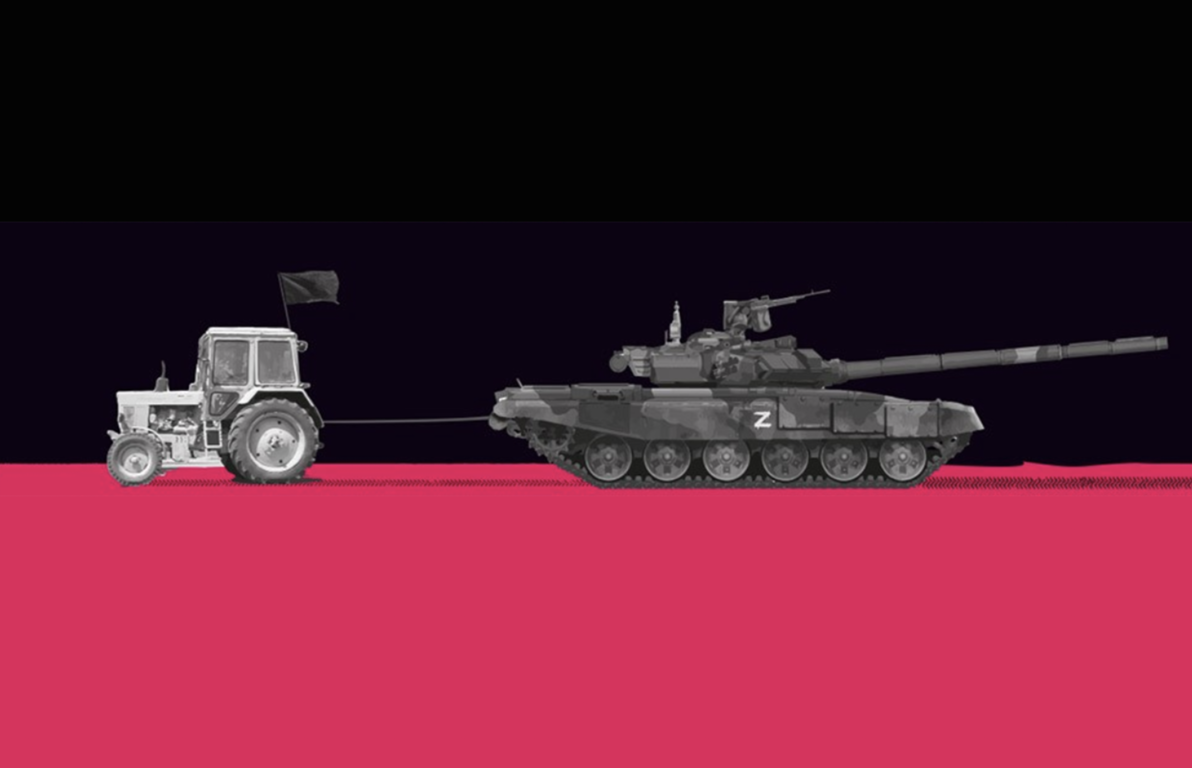

These are the two demands voiced by Ukrainian Left with which I can identify: supply weapons and enforce sanctions. There is no other way. I know there are arguments against both of these demands, and while I still try to find the words to convince people who are opposed to one of them, usually weapons, I have little to say to those who are against both dimensions of applying pressure. Being against both is tantamount to washing your hands of the conflict.

Destroyed Russian military machinery on the highway between Kyiv and Zhytomyr / Maxym Marusenko / NurPhoto / REX / Shutterstock

What do you expect would be the effect of sanctions? Many leftists in Germany argue that full-scale economic sanctions targeting groups beyond the Russian elite would push the population to rally around the flag and generate even more support for Putin and his war. Earlier you said in an interview that you do not expect a protest movement in Russia strong enough to stop Putin, but you saw a chance for an elite rebellion against Putin. With regard to that perspective, what kind of sanctions would be useful to stop the war in Ukraine?

The prospects for a grassroots uprising against the war were very low from the beginning. The repression of any opposition and free media has been going in Russia for years, and the war only made things worse. The longer the conflict drags on, the less I believe in massive anti-war protests.

I also agree that there is a strong possibility that sanctions, combined with Russia’s massive propaganda machine, could lead to increasing support for the war inside Russia. But if there was no chance of a mass anti-war movement from the very beginning, should this factor be considered when debating sanctions? Instead of asking whether sanctions can diminish the almost non-existing anti-war movement in Russia, shouldn’t one ask what (if anything) could trigger the development of that movement?

In other words, in my eyes it seems like sanctions are not part of this equation anyway. I’m also not sure it’s worth discussing the chances of elite rebellion at the moment. I don’t believe that sanctions are the main factor here, either. They’ve definitely led to some “dissident” sentiments among Russian elites, but whether these sentiments will lead to something depends on many other extra-economic factors which are outside of our control.

I suspect that in German debates the argument against sanctions is that it could have a more disastrous impact on the population in general, rather than on Russian elites, who have more resources and can hide their assets abroad. This argument is valid, of course. But it is valid only so far as you consider sanctions as a kind of punishment. I don’t support the idea that sanctions are intended to punish. That should be left to an international tribunal — for the war criminals, the propagandists, for those who ordered, concealed, and executed crimes against humanity in Ukraine.

The main logic of sanctions, as I see it, is to cut into the material resources needed to wage the war. The war economy must be stopped. Unfortunately, social reproduction in capitalism fully depends on the economy, and there is no way to stop the war economy without disturbing the social reproduction of people living in Russian society. Moreover, however, without stopping the war economy there is no way to stop the destruction of the social reproduction of Ukrainian society, and, literally, to stop the escalation of violence and save lives.

This is the point where one has to make choices. This choice may be hard for German leftists. As far as I know, it is not a hard choice for anti-war leftists in Russia. And it is definitely not a hard choice for Ukrainian leftists. This is not because we’ve become nationalists. We are materialists, and this choice is strictly conditioned by the material reality of the brutal Russian invasion.

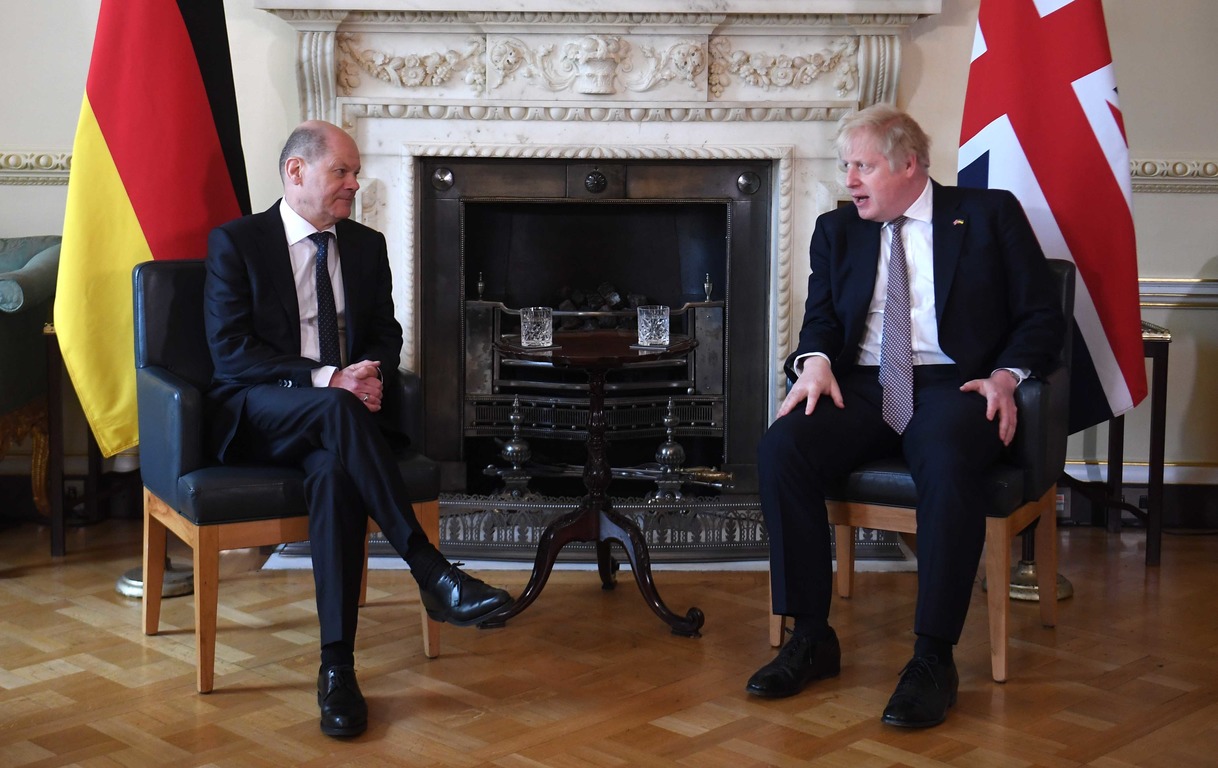

Boris Johnson, U.K. prime minister, and Olaf Scholz, Germany’s chancellor, during their bilateral meeting inside in London are discussing steps to contain Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Friday, April 8, 2022 / EPA / POOL

At the moment, the Ukrainian and Russian governments are negotiating a ceasefire and a diplomatic solution of the conflict. What do you expect from these peace talks?

I don’t think that the war will end soon. The delusions of the Russian government, which became obvious with its blitzkrieg plan at the beginning of the war, helped Ukrainian society mount a spirited defence to some extent. But they are also very dangerous in terms of the negotiations. I also view the current developments, not to mention the rhetoric coming from the Russian government and official propaganda, as signs of further escalation.

Because it won’t end soon, it is very hard to predict what these negotiations, which could drag on for months if not for years, will ultimately yield. The negotiations have several components — provisionally we can call them ideological, territorial, and geopolitical. The ideological component consists of the deluded Russian goals of “de-nazification” and “de-Ukrainization” — I don’t see any point in discussing them now, especially after they were used in the genocidal narratives of Russian propagandists.

The territorial component relates to the control of territories and international recognition of this control. This part will depend heavily on the battlefield and the material — military and economic — conditions of the war. Here I want to stress the danger of a position, shared by some leftists, according to which Ukraine should concede some or all of the newly captured territories. After all the stories of violence and repression in the occupied territories, ceding these territories to Russia would mean ceding the population to the disaster of Russian rule.

Finally, there is a geopolitical dimension — Ukraine’s neutral status, security guarantees, etc. This was pushed to the extreme by Russia, as by attacking Ukraine it has massively bolstered support for joining NATO in Ukrainian society, and triggered shifts in public and official opinion in some other non-NATO countries bordering Russia. Nothing else could be expected when people see the brutality of the Russian invasion: NATO status is perceived as the only way to guarantee the Russian military won’t attack.

The security dimension plays a crucial role now. I don’t know how these security guarantees for Ukraine may look in the end and how effective they will be. Especially taking into account that their effectiveness will much depend on Russia’s internal trajectory — as Russia is the main threat to our security. The stronger Russia and its aggressive militarism will be, the lesser the chance that any guarantees will be effective.

On a personal level, I came to the realization during our long trip to personal safety that, even after the war ends, I won’t feel secure in Kyiv unless some dramatic change happens in Russia. Something like defascistization and demilitarization. Without these changes, even when some kind of peace is negotiated, there is a big chance that one morning — maybe in months, maybe in years — I will wake up to bombing again.

Your question was about expectations for the peace negotiations, but I want to add another expectation, which is extremely important for the needed change in Russia after the war. This expectation is that there will be an international tribunal addressing the crimes against humanity conducted by the occupying Russian army. Otherwise, no long-term security and peace is imaginable for the people of Ukraine and other countries in the region.