Teklehaymanot (Tekle) Weldemichael grew up in central Tigray. He received his Bachelor's in Ethiopia before spending several years between Ethiopia and Norway, where he continued his studies in Human Geography. A month before the war in Tigray began, Tekle submitted the final draft of his dissertation and was preparing to take a break and finalize his studies. However, as violence between local and foreign forces and the Ethiopian government had erupted in his home region, he shifted his focus from academic research in geography to public exposure in Europe of the war in Tigray. Tekle writes and comments on the war, its origins, chronology, the peace agreement, and the lack of visible improvements in the region.

We sat down with Tekle to discuss the historical context of the war, Ethiopia's colonial legacy, the challenges of life in the diaspora, and the challenges in balancing an academic career with advocacy for issues close to home.

Could you tell us more about your academic journey and the project you are currently working on?

I'm an associate professor of human geography at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. I grew up in central Tigray in Northern Ethiopia and there I graduated with a bachelor’s degree so I then moved to Norway for my MPhil and PhD studies with a short stay between them back in Ethiopia. During my PhD, I focussed on how conservation policies in the countries of the greater Serengeti ecosystem affect people who live close to national parks and on the ways authorities legitimize violence in that context. I looked into how capitalist conservation plays out in the context of countries that have been through colonial rule and have experience with post-colonial practices.

I submitted my thesis on October 2, 2020, preparing to take a break before the defense. However, the war broke up a month later, shifting my concern from scholarly debates to the crisis in Tigray. For the past three and a half years, despite holding a post-doc position on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in urban Norway, I concentrated on Tigray due to the urgency of the situation.

When you have to fight fire all the time, you see a lot of propaganda and a lot of violence taking place, and as an academic you are supposed to make sense of this. My writing shifted from long analytical articles to shorter communications addressing the ongoing crisis, covering topics like famine, border violence, and the environmental impacts of the war. I also have an upcoming article on the use of medicine as a technology for genocide and violence.

Map of Ethiopia showing Tigray Region at the northern country's border

This situation is quite familiar. In 2022, many Ukrainian scholars relocated to other countries, primarily within the EU. They are now working in paid academic positions while also engaging in non-academic publications and advocacy efforts.

Now, could you tell us about Tigray and Ethiopia? In Ukraine, both academic and non-academic research mainly focus on Western Europe, the USA, and Russia, with little coverage of events outside these regions. Could you describe life and the country's political landscape before the war, and also tell us about the main extant social issues?

First, I must say that I sympathize deeply with Ukrainians and others facing similar horrors, such as in Gaza. For many, these events are plain facts lurking in the newsfeed, but for me, they have been my reality for almost four years. This cycle of violence has persisted for decades, thus I truly sympathize with people like you experiencing similar situations.

I’ll start answering your question by describing my personal background. I was born and raised in a small village in central Tigray, near Aksum, an ancient city with many historical monuments. My village was close to the site where Ethiopia defended itself against Italian occupation in the 19th century, contributing to Ethiopia's status as a country never formally colonized during European colonial rule.

My parents were small-scale farmers, growing crops primarily for our consumption but also to earn extra money for schooling. We also had a beautiful garden with fruit trees, rather a rare sight amidst dry landscape. I am the middle kid of seven siblings, all of whom are educated, despite our parents not having an education. Most of us have at least a bachelor's degree, and I am the only one who pursued a PhD. My siblings have all moved out, and only my parents remained on the farm when the war started.

Before the war, life in Tigray was relatively stable. The region wasn't wealthy, but the institutions were functioning there. The health and school systems worked well enough for children of farmers like myself being able to attend school and university for free. This system emerged from struggles in the 1970s and 80s, with Ethiopia remaining independent of European colonialism.

Before the war, Tigray was best-known for its rock-hewn churches, dating back to the 4th and 5th century. Here, a priest leaves the Daniel Korkor Church in the Gheralta Mountains. Image: Oscar Espinosa / Shuttertstock

It is safe to say that although Ethiopia is often presented as a republic, it is essentially an empire that survived European colonial expansion. In the 19th century, while European powers, Britain, France, and Italy, were dividing Africa, Ethiopia was at the same time expanding its territory and competing with those empires. This expansion was not peaceful and involved significant violence against indigenous populations beyond the northern highlands. Although previously these territories kept their own sort of autonomous governance, during the expansion Ethiopia was centralizing power and diminishing local self-rule. This led to numerous struggles, particularly in the latter half of the 20th century.

We have had a lot of ups and downs at that time. In 1974, the last Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie[1] was deposed amidst growing dissent, particularly amidst the educated youths who were unhappy with being forced to assimilate into a singular Ethiopian identity under imperial rule. Now, he’s kind of worshipped in the Black community. For example, Jamaicans sing about him, and many in the Caribbean see him as a Messiah. This reverence stems from Ethiopia's history as a Black nation, symbolizing independence, at once also playing a role in suppressing the population within the country itself.

After the overthrow of Haile Selassie I, the situation was not getting much better. The military took power, leading to 17 years of severe violence[2]. This period also saw the rise of many liberation movements, including the Eritreans, Tigrayans, and Oromos.

The Tigrayans managed to organize effectively and overthrow the government in 1991, leading to a new constitution in 1995. This constitution transformed Ethiopia into a federation, theoretically allowing regions some autonomy and even the right to secede. However, in practice, implementing this was difficult. The central elite, mainly urban and ethnic Amhara, opposed the federation, preferring a unified Ethiopia.

Therefore the centralization of power continued, leading to significant disparities, with Addis Ababa holding most of the country's infrastructure and capital. In a city with around 5% of the state population around 60% of the country's infrastructure and capital was concentrated. This centralization caused widespread protests between 2014 and 2018, resulting in the resignation of the then-prime minister and the rise of Abiy Ahmed Ali.

When Abiy Ahmed Ali[3] came to power, there was initial excitement and hope for democratic reform. Many Western actors hailed him as a reformist who would transform the country into a democratic state and unify it. However, the concept of unity varied across the country. For Tigrayans, unity meant recognizing their diversity and granting them recognition and acceptance. For others, unity meant returning to the imperial model, requiring people to drop their identities and assimilate into a singular Ethiopian state.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali poses after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, December 10, 2019, in Oslo, Norway. Image: Erik Valestrand

Initially, he got support from all groups and appeared committed to upholding constitutional rights. However, within a few months, his rhetoric began to favor a more urban identity, moving away from pro-poor economic planning towards liberal capitalist policies. This shift disrupted the infrastructure that had enabled people like me to access education and opportunities, leading to significant tensions.

He began dismantling regional authorities, even though regions were entitled to have their own councils and elected governors. Within his first year in office, he sent the army to depose regional governors and override regional councils' mandates, affecting all regions except Tigray, where resistance had persisted until the war started in November 2020. This complex history explains the situation before the war and how we ended up in the war.

We know the war in Tigray officially ended with a peace agreement in 2022, yet many problems and unresolved issues persist. Could you highlight the war’s key events and explain the current situation in Tigray? What are the various opinion camps on the consequences of the conflict and how people have reacted? Is there any unity around one understanding of the war?

It is, of course, still a very complicated story to talk about. The rise of Abiy Ahmed as prime minister in 2018 marked a significant shift, resembling the pre-1991 imperial period. His rhetoric and state propaganda reflected this shift, presenting voices not agreeing with new policies as betrayers of the country. This was evident in the media and public discourse over the past six years.

What led to the final trigger causing the war was the elections held every five years in Ethiopia since 1995. The sixth election was scheduled for May 2020, where regions would elect members of parliament at the federal level and regional councils.

However, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear that the federal government was reluctant to proceed with the elections. There were extensive discussions and back-and-forth about whether the election would take place. When the pandemic struck, the government used it as a justification to postpone the election indefinitely.

The Tigray regional authorities decided to hold their own election on September 9, 2020, even though the federal government and the National Election Board, closely aligned with the federal authorities, did not permit them. In response, the federal government declared that it no longer recognized the regional authorities, citing the unauthorized election. They also halted federal subsidies and restricted road and air transportation to the region, effectively blockading Tigray. This escalation significantly exacerbated tensions, contributing to the outbreak of war.

Voter registration for upcoming elections in the Tigray Region, August 2020. Image: Mulugeta Atsbeha

On the night of the American election, which was held from November 3rd to 4th 2020, I was chatting with friends in a Twitter group, including some based in Tigray. One friend in Mekelle mentioned firing sounds wafting from the suburbs of the city. Just 20 minutes into the conversation, she stopped responding. That was the outbreak of the war.

I went to bed around midnight but couldn't sleep due to the gunshots and rising tension. At 2 am, I woke up sweating and frightened. When I checked my phone, I saw that the Prime Minister had declared war on Tigray, stating that he had ordered the army to take "law enforcement" measures in the region.

The Prime Minister claimed that the war started because the TPLF[4] or Tigray regional authorities had attacked army bases in the region. For several weeks, we were in a state of war. During this time, I had no idea where my family was or whether their village and the towns where my siblings lived were occupied by foreign forces.

This continued until November 28th, when the Prime Minister announced that they had defeated the Tigray authorities and captured Mekelle, declaring the war over. However, we knew from the beginning that it wasn't just the Ethiopian army involved. The entire national army of Eritrea[5] had invaded Tigray from the north, penetrating cities in the middle of the region. Ethnic militias from the Amhara region were also invading western Tigray, carrying out massacres and severe violence.

We heard about the war's atrocities from the refugees fleeing to Sudan, who were talking about the violence they witnessed. After the declaration of victory, limited access was granted to foreign media and UN agencies, allowing some information to pop up. Videos and stories from aid workers revealed the extent of the violence. The region had been intentionally cut off from all communication, which is why my friend disappeared from our conversation. When the Ethiopian army arrived, the Tigrayan authorities had evacuated Mekelle to avoid fighting in the city. However, the shelling continued even without active resistance. For the next eight months, fighting occurred across villages and districts in Tigray.

Captive Ethiopian soldiers in Mekele, the capital of Ethiopia's Tigray region, July 2, 2021. Image: YASUYOSHI CHIBA / AFP

In late June 2021, the Ethiopian army suffered a major defeat, with about 10,000 soldiers captured, forcing the government to withdraw its troops and declare a unilateral ceasefire. The Prime Minister claimed this was to allow farmers to cultivate their land, but it was clear the ceasefire was due to military setbacks. The region was then effectively besieged, with no access to banking, telecommunications, or power, and minimal humanitarian aid.

In November 2022, a formal ceasefire agreement was signed in Pretoria[6], mediated by the African Union, the U.S., and other actors, officially ending the war and resuming some dialogue between the federal government and regional authorities. However, the siege was not fully lifted, and significant challenges remain.

Eighteen months after the agreement, over a million internally displaced people still live in dire conditions across Tigray, and around 70,000 Tigrayans are stuck in refugee camps in Sudan, which is itself in crisis. The ceasefire has not led to the hoped-for improvements, leaving many people in desperate situations.

The war has not only displaced people, leaving many families homeless across the country, but it has also severely affected farming, which is a crucial economic sector for the region. How has the conflict impacted ecology, agriculture, sustainable development, and the environment in Tigray?

I’ve seen what has been happening in Ukraine and Gaza, and that is horrifying. All these images exhibit the enormous scale of the damage. In contrast, it has been difficult to see the same in Tigray, obviously because of the communication blackout, but also due to the lack of access to sharing platforms where they could share what they have seen. However, the satellite images don't lie.

Villages in western Tigray, which used to flourish before, have been torched, having visible scars on the ground. Tigray is an ecologically fragile, tropical mountainous region prone to erosion. The war has forced a third of the population from fertile southern and western Tigray into the more fragile highlands. Without access to electricity, people rely on local resources, leading to significant deforestation. Trees that were carefully managed and recovered over decades have been cut down, accelerating soil erosion.

The conflict has also caused a near-total collapse of an agricultural sector. Soldiers have been systematically dismantling agricultural infrastructure, including equipment and farm supplies, destroying fruit orchards. The siege has prevented access to necessary replacements for equipment, fertilizers, and seeds, drastically reducing agricultural productivity. This devastation means that the agricultural sector will take a long time to recover, significantly affecting food security and economic stability in the region. The war has not only displaced people and destroyed homes but also crippled the region's core economic and ecological systems, making recovery an essential challenge.

Farmer Kiros Tadros plows his land in the southeastern region of Tigray after Eritrean soldiers took the food, livestock, and seeds from his village. Image: National Geographic

Being at once a scholar and someone with a deep concern about your home region, how do you handle the need to present your stance clearly when writing about it? I imagine Western academia often doesn't perceive this well, and you might have been accused of lacking objectivity or being biased. How do you deal with such situations, especially regarding the war in Tigray?

Yes, this is a significant challenge. Before the war, I wrote about Kenya and Tanzania, and my work was recognized as credible. However, when I write about Tigray, where I have extensive knowledge, my work is often treated as a private opinion. Editors frequently ask for citations from "credible sources," which usually means Western journalists. It's painful to be considered less credible than someone with limited knowledge or experience.

This issue is compounded by the lack of scholars writing on Tigray compared to Ukraine, for instance. In Tigray, very few academics are covering the topic, making it even harder to get accurate information recognized. Established academics often avoid writing about Tigray, claiming it's too complicated, which is ironic because our job is to explain complex issues.

Despite not being a highly established scholar, I see my role as giving a voice to those who can't articulate their experiences. Many survivors in Tigray struggle to express what they've been through. Our job is to provide them with the language to relate their stories to others — such as those from Ukraine — and to make their experiences understandable.

This situation has pushed me to write more opinion pieces and short communications, as my perspective is often seen as a biased opinion rather than an expert analysis. Nonetheless, I find motivation in the need to share these stories and provide insight into the reality of the situation in Tigray.

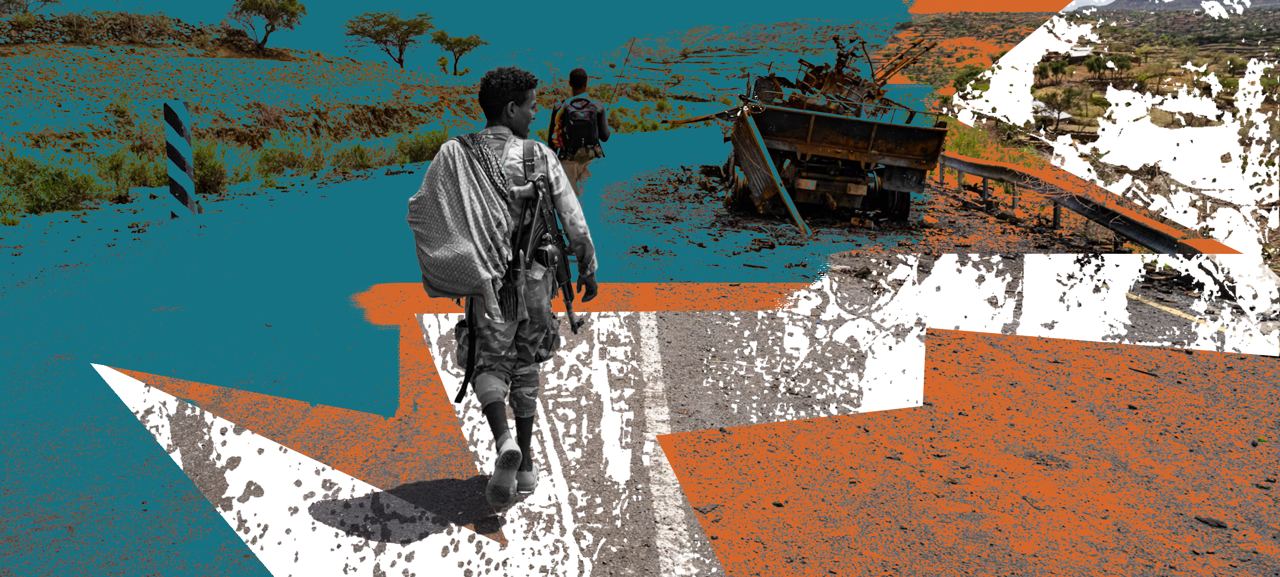

Tigrayan soldiers pass wreckage from the war as they travel by foot on a road east of Abiy Adi. Image: National Geographic

In Ukraine, scholars living abroad often face hostility from academia. They're perceived as disconnected from the experience and either not being immersed enough into the context or lacking the right to comment because they're not in Ukraine i.e. speaking from a privileged position. As a result, they experience hostility from those still in Ukraine, coupled with survivor's guilt. Do you face similar issues with your compatriots?

I can relate to the survivor syndrome part. Before the ceasefire agreement in 2022, I felt a responsibility to write about Tigray because there was no one else able to report it. When the agreement was signed and communication was restored, we hoped people in Tigray would share their experiences. However, there's a significant difference in the language used by diaspora Tigrayans and those still in Tigray. Locals often struggle to express what they've witnessed, while those of us abroad have developed a way to communicate these stories more effectively.

This situation puts me in a difficult position. I feel torn between writing about current events and allowing people on the ground to speak for themselves, knowing that many still find it challenging to communicate. We are making efforts to help them share their stories more.

In terms of hostility, I haven't experienced the same as you describe. Instead, I've received respect from people back home, who appreciate that I did what I could when they couldn't. This has been humbling and has made me feel a greater sense of responsibility. The difference in our experiences might be due to the varying levels of access to communication. Tigrayans had very limited access during the war, unlike Ukrainians, who, despite the terrible situation, had more opportunities to get across to the outside world.

Tigrayans stand in line to receive food donated by local residents at a reception center for the internally displaced in Mekele, in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, on May 9, 2021. Image: AP

Since 2022, decolonization has gained significant attention in Ukraine, contrasting with the restrained discourse of the 90s post-Soviet Union. With new waves of decolonial studies, we’re reexamining how countries could decolonize and address Russian imperial politics.

Historically, decolonial studies viewed Russia as an alternative to Western empires. Now, Ukrainians see it as an imperial force and want to share this perspective internationally, reflected in governmental speeches and academic discussions. They emphasize that the West overlooked Russian imperialism and that Ukrainians can teach how to deal with it.

However, Ukrainians face counter-discourses, especially from international organizations like the African Union, which argue that Eastern Europe is appropriating the colonial discourse, traditionally tied to race. How do you see this debate? Should there be another term, like "post-socialist development," for the Soviet Union experience? Or can colonialism and decolonization apply to Eastern Europe as well?

Yes, that's a relevant question. There's a similarity between the Soviet and Russian empires and their imperialisms. While Ukraine and former Soviet republics gained independence in the 90s, Ethiopia remains an empire that has resisted dissolution. At a conference in London last year, someone from the Caribbean noted that Ethiopia symbolizes freedom and Pan-Africanism, which has concealed its imperial nature. Similarly, Russia is often seen by the African Union and Pan-African movements as an alternative to Western imperialism.

Framing the discussion about colonialism requires a different approach when considering Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. This differs from the traditional Western colonialism narrative. I am looking for this approach through my personal experience. During the war, I struggled emotionally, because I knew my family suffered, but I couldn't communicate with them. My department suggested seeing a psychologist, but I found it unhelpful as the Norwegian psychologist became more depressed by my stories. One way I coped was by reading about other struggles. The Ukrainian Holodomor and Frantz Fanon's work on Algeria were particularly relevant. Fanon, for example, discussed how, as a psychiatrist, he couldn't address his patients' struggles through simple psychiatric help alone. He realized the deeper issue was the imperial occupation of Algeria by France. This applied to much of the African continent at the time. Similarly, my suffering couldn't be solved by therapy alone but needed a broader fight against the underlying causes.

This understanding helped frame how I view the struggles faced by Tigrayans, Ethiopians, and Ukrainians in their current conflicts.

Abeba Girmay (at center) and Fetlework Amaha (at left) sit on the concrete grave of nine family members and neighbors at the Abune Aregawi church in Abiy Adi. Image: LYNSEY ADDARIO

Yeah. So, I'm curious about the Tigrayan diaspora in Norway and Europe. Are there any specific campaigns or public events advocating for the Tigray cause and raising awareness about the war and its consequences? Additionally, did you experience irritation with people who knew nothing about the war, didn’t react, or offered simple comments like "take care"? How do you handle this irritation, especially with those around you who aren't interested in your problem?

Yes, we have a small but vocal Tigrayan diaspora here in Norway and across Europe. This small number is often framed in a way that highlights violence against Tigrayans, suggesting that a small group can be sacrificed for the greater good of the country. Despite our numbers, we are active, trying to raise awareness and advocate for our people.

In Norway, and especially in Oslo, we organize demonstrations, online discussions, and public events to keep the issue visible. The larger networks in the US, UK, and other parts of Europe also contribute significantly. The most helpful aspect for me has been the support from people close to me, those living in the same city. They truly understand the scale of the pain and burden we’re going through, especially those who have lost family members.

Regarding irritation, absolutely. Being in a global department, I often felt like a killjoy when discussing the situation in Tigray. Casual conversations by the coffee machine would end awkwardly, with people offering superficial comments like, as you said, "Take care" because they didn't know what else to say. This avoidance is understandable but frustrating.

There's a saying in Tigrinya, “When you eat a fig, you don't open it”. You don't want to see what's inside. You just eat the fig as it is. This reflects how people often don't want to know what's going on in the rest of the world. They prefer not to dig deeper into difficult situations, preferring to remain unaware of the harsh realities others face.

However, over time, I realized I couldn't expect everyone to engage deeply with my story. It’s a coping mechanism for many, a way to avoid the harsh realities others face. Now, I don’t mind if people don’t want to talk about it. I’ve come to accept that not everyone will understand or want to engage with the complexities of such crises.

Tigrayan protesters, seen here outside the United States Embassy in South Africa in January 2022, insist that Ethiopia is carrying out a genocide against the people of Tigray. Image: EPA-EFE / Kim Ludbrook

Yeah, I understand. At the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I wanted everyone around me to be aware, listen, and ask people from the region about what was happening, instead of relying on external experts. But over time, I got used to it, and it's better for my mental health now.

So, let's move to the concluding question. What do you think the international community, including neighboring countries, international organizations, and people from other regions who aren't directly related, could have done better in this situation? How can they still help to effectively resolve or at least improve the situation in Tigray compared to how it is now?

The international reaction, or lack thereof, to the Tigray crisis has been incredibly disappointing. As a human geographer, I study the international system and have always believed that something as horrific as what happened in Tigray would require an urgent response from the UN system. Unfortunately, that didn't happen.

The coverage of this crisis has been inadequate, and the scale of the tragedy—about a million people killed, entire districts emptied—has not received the attention it deserves. The international system seemed ill-equipped to respond, partly because the conflict was framed as a domestic law enforcement operation, which limited the international community's ability to intervene effectively. This situation calls for broader discussions on how the international community should respond to such crises. In one of my opinion pieces, I mentioned that Tigray has been a testing ground for future conflicts, with unprecedented use of weapons and violations of international laws and norms. The two-year blockade of a region with 5-6 million people without an adequate international response is unprecedented.

We need to rethink how we approach these situations. The UN system, as it stands, seems unable to handle modern conflicts characterized by drones, unmanned vehicles, and nomadic warfare. International laws and norms need to adapt to these new realities. It's time for researchers, academics, and politicians to sit down and discuss how to respond to crises like those in Tigray and Gaza. The current system is outdated and incapable of addressing these emerging types of conflicts effectively.

Villagers return from a market to Yechila town in south-central Tigray walking past burned vehicles, in Tigray. Image: Giulia Paravicini / Reuters

I remember studying the post-colonial foreign policy of Belgium towards its former colonies, like the DRC, Rwanda, and Burundi, and the atrocities that occurred there in the latter half of the 20th century. Recently, I read a memoir by Jane Goodall, the founder of the Jane Goodall[7] Institute, who studied chimpanzees in Tanzania. In her book, she briefly mentioned the violence happening across the lake in Rwanda and the DRC, noting that she felt safe in Tanzania despite the brutality nearby. She acknowledged the violence but reacted very calmly, almost detached. This reaction, especially from someone who spent years in the region, highlights a certain disconnection in the Western perspective towards such events. It’s telling about how distant and unengaged the Western response can be to significant crises unfolding nearby.

Considering this, what do you think could have been done differently by the international community, neighboring countries, and international organizations to better address and resolve the situation in Tigray? What actions can still be taken to improve the current situation?

That's a good point. I've had foreign friends visit Addis during the height of the genocide in Tigray. Even though Addis, the capital, had hundreds of thousands of Tigrayan residents, many of whom disappeared or were sent to concentration camps, a foreigner visiting the city might not have noticed anything amiss. They might hear rumors or brief mentions, like "some Tigrayans have been arrested," but the full scale of the violence is often minimized or overlooked.

This detachment is evident in various reports that briefly mention the situation in Tigray in passing, without fully acknowledging the severity. It's telling about how the subjects of violence are perceived and how their suffering is often downplayed or ignored. This kind of reporting is very disappointing and reflects a broader issue in how such crises are communicated to the international community.

Footnotes

- ^ Haile Selassie I (1892-1975), Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974, was a key figure in modernizing Ethiopia, founding the African Union, and inspiring the Rastafarian movement, despite being overthrown in a coup and dying under mysterious circumstances. Revered by many for his contributions to Ethiopia and African unity, his legacy remains controversial due to his autocratic rule and the unfulfilled promises of his reforms.

- ^ After Haile Selassie was deposed in 1974, the military junta known as the Derg, took control of Ethiopia, implementing Marxist-Leninist policies and brutally repressing political opposition during the notorious "Red Terror." The Derg's rule, characterized by radical land reforms, widespread violence, and economic hardship, ended in 1991 when they were overthrown by a coalition of rebel groups.

- ^ Abiy Ahmed Ali is the current (2024) Prime Minister of Ethiopia, having taken office in April 2018. He is known for initiating significant political and economic reforms in Ethiopia, winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for his efforts to resolve the long-standing conflict with neighboring Eritrea. However, his tenure has also been marked by internal conflict, most notably the ongoing war in the Tigray region.

- ^ The Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) is a political party and former guerrilla movement in Ethiopia. It played a key role in overthrowing the Derg regime in 1991 and was a dominant force in Ethiopian politics for nearly three decades. The TPLF was the leading party in the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) coalition, which ruled Ethiopia until 2018. The TPLF has been at the center of the conflict in the Tigray region, fighting against the federal government led by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

- ^ Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993 after a 30-year war. Relations deteriorated into a brutal border war with the TPLF-led Ethiopian government from 1998 to 2000, resulting in a stalemate and prolonged tensions. A significant thaw occurred in 2018 when Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed initiated a peace process, leading to the normalization of diplomatic relations. However, Eritrean iinvolvement in the Tigray region has complicated the relationship again.

- ^ A peace deal between the Ethiopian Government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) signed on November 2nd in South Africa.

- ^ The book in question is "Seeds of Hope" by Jane Goodall, published in Ukrainian by Borodaty Tamarin Publishing and translated by Tetiana Kidruk in 2024.

Talked to Tekle: Oleksandra Terentyeva

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva