On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. However, this was only a new stage, as the conflict dates back to 2014, when Russia seized Crimea and the armed conflict in Donbas began. Russia's role therein had been debated until 2022, once the invasion revealed that it was a Russian operation against the Ukrainian government, rather than a local uprising against Kyiv's policies. To understand how the war between Russia and Ukraine began and what role Donbas residents and elites played in it, we spoke to Serhiy Kudelia.

Serhiy Kudelia is a political scientist at Baylor University in the United States. His research interests include armed conflict, political regimes and institutions, and institutional design. His publications mainly focus on post-Soviet Ukraine, and since 2014, he has been writing about the war in Donbas for various academic and analytical publications.

This year, Oxford University Press published his book Seize the City, Undo the State: The Inception of Russia’s War on Ukraine. This book was the result of many interviews and field research conducted by Serhiy Kudelia in Donbas in 2014–2020.

Iaroslav Kovalchuk: The subtitle of your book is “The Inception of Russia’s War on Ukraine,” which immediately suggests the central role of Russia in the events in Donbas in the spring of 2014. However, in your analytical text, which you published shortly after those events, you focused on the internal sources of the conflict. Does this subtitle mean that your analysis has changed since then? What role did Russia play then?

Serhiy Kudelia: When we analyze the beginning of the Russian Federation’s armed aggression against Ukraine, we see that both the annexation of Crimea and the armed campaign in Donbas that began in March 2014 are elements of a broader plan to take over Ukraine, which has taken on a different scale in 2022. During my field research in the region, I reconsidered much of what I had written in 2014. This is a normal research process because I developed my initial ideas about how the armed conflict in Donbas unfolded by observing the events in Donbas from my office in Texas.

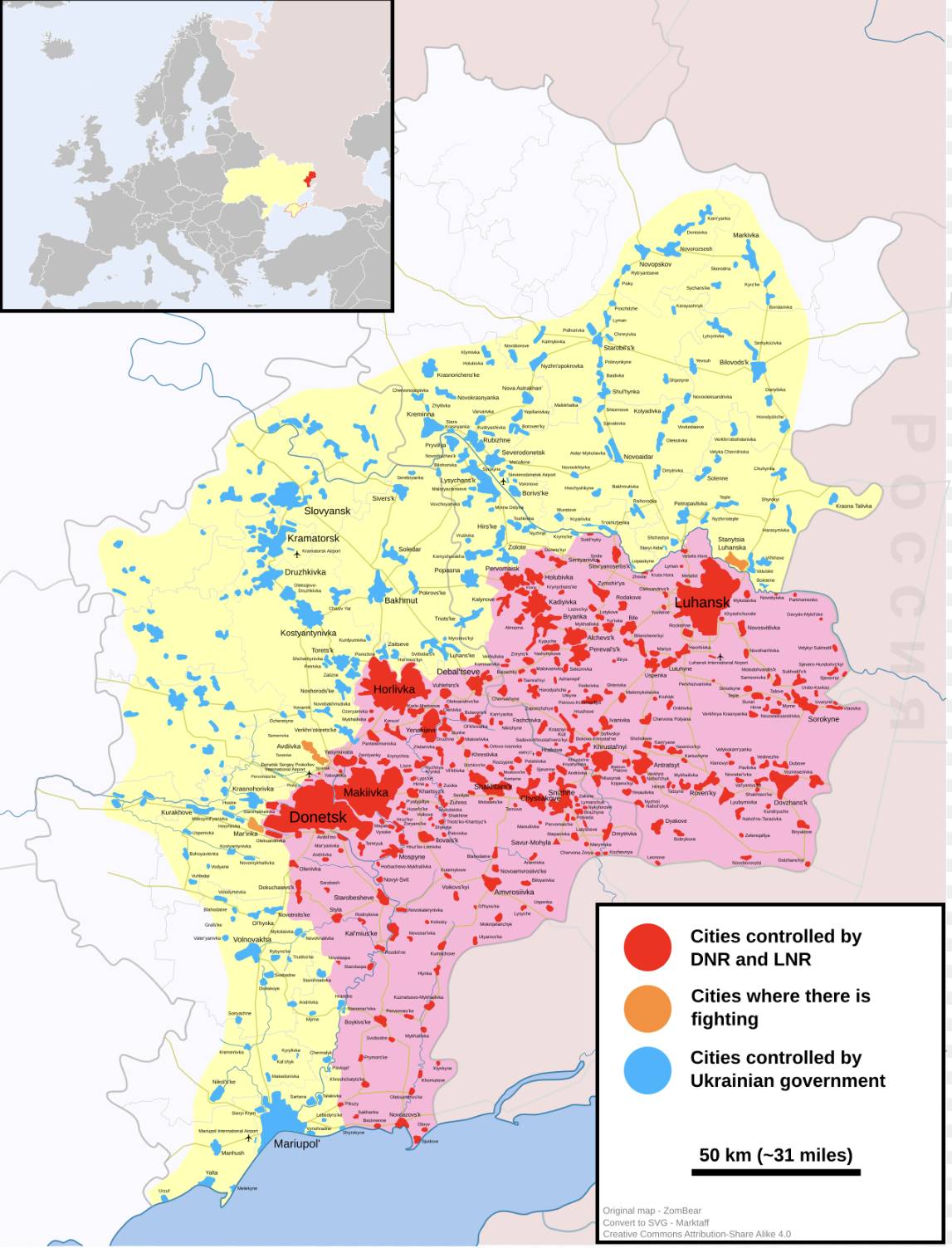

It was a far from complete analysis with many gaps. To fill those gaps, I developed my research plan, which began in 2015 with a large-scale survey trip to 8 cities in Donetsk and Luhansk regions. I talked to ordinary civilians who were observing these events. My first task was to understand how these people viewed the armed men who appeared for the first time in their cities and said that they were now the authorities. During this first research trip in 2015, I realized that our perception of the seizure of the region in 2014 was completely wrong. It wasn’t just my perception, but also that of most Ukrainian citizens who observed these events from the outside. This is due to how the official authorities presented information about the seizure of the region. At the time, the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) maps showed fully-colored areas allegedly controlled by the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR). And then we saw the territories that were being liberated by Ukrainian troops. Gradually, during May–August 2014, the territory controlled by the separatists was decreasing, while the territory liberated by Ukrainian troops was increasing. This is how Ukraine’s military progress in liberating the territory was visualized.

Map of the conflict as of February 22, 2022. The territory controlled by the Russian Federation, DPR, and LPR is marked in red, and the territory controlled by the Ukrainian army is marked in yellow

When I arrived and started conducting surveys in different cities in 2015, I realized that a significant part of the cities was not controlled by the separatists at all. That is, no one controlled some of these cities. There was no Ukrainian government there, but neither was there direct forcible control by the militants. This was my first research discovery. It further pushed me to try to understand what exactly could explain this variation in power and administrative control in different parts of the region. First, it was necessary to establish who controlled what in different cities of the region. Then I had to understand how this could be explained. This was the first step.

Then, in 2018–2019, when I started doing field research in different urban agglomerations of Donbas, I saw how important the role of Russian agents was: Girkin, Bezler, and others who followed them or acted separately. I have devoted a separate chapter to analyzing the role of these Russian agents in the armed conflict and showing how critical they were to its outbreak. On the other hand, many of my hypotheses related to the role of internal factors were confirmed. In particular, the emotional reaction of local residents to the way power was transferred in Kyiv or to the collapse of the state’s security apparatus in these territories, which created favorable conditions for their capture.

In my book, I try to explain the mechanism of the region’s seizure more clearly and emphasize Russia's role at the initial stage, namely the agents who represented Russia. On the other hand, I explain that without the collaboration of local elites and residents of Donbas, its complete capture would not have happened. While the number of people who represented Russian agents in Donbas at that time was only enough to organize people ready to participate in the armed conflict on the ground, they were not enough to completely seize such a large region as Donbas.

As you note in your introduction, the politicization of the war in Donbas, as well as the limited access of researchers to the perspectives of both sides of the conflict, often hinder the study of the conflict. What impresses me about your work is the diversity of sources and the ability to disassociate yourself from value judgments to describe the dynamic relationship between different participants in the separatist movement. This picture is far from the stereotypes of a bunch of “Kremlin puppets” without a real social base.

It seems to me that one of the key obstacles from the very beginning of the analysis of the events in Donbas was the perception of a certain part of the research community that the analysis of the causes of this conflict and its course had to fit into the logic of the information war against Russia. So, it was expected that researchers of this conflict would a priori accept the assumptions made by the Ukrainian authorities. Any research judgments that contradicted these assumptions or tried to show other sides of the conflict that the Ukrainian authorities refused to talk about or ignored were perceived as an attempt to play along with the opposing side, i.e. Russia. This made researchers who tried to analyze the conflict from different perspectives targets for accusations of collaboration with Russia or playing along with Russian narratives.

Unfortunately, this way of conducting the debate started from the very beginning of 2014. It created major obstacles to research and denied the possibility of independent academic research expertise. It was also accompanied by a distortion of the opinions, judgments, and conclusions of a significant number of researchers who also tried to point out the internal causes of the conflict and were stigmatized for this in the research community.

Now, after 10 years of research on those events and after we have already realized how different the events of 2014 are from the events of 2022, it seems that the nature of the discussion has changed. Maybe we can be more open to understanding that in 2014 there was no black and white conflict between Russia and Ukraine, but there were many different nuances that are detailed in my book. So, I hope my book will open the discussion to different perspectives.

At the end of March 2014, the wave of rallies in response to Yanukovych’s ouster began to subside. Explaining the reasons for the resumption of the separatist movement in mid-April, after the launch of the ATO, you write in your book: “Just like the brutal beatings of students by riot police triggered mass mobilization and launched the Revolution of Dignity in Kyiv, the scenes of wounded and killed civilians in altercations with Ukrainian military reignited mobilization behind the separatist cause in Donbas.” This is an opportunity for you to analyze the role of emotions in politics. You distinguish between fear, which often has a demobilizing effect, and indignation, which motivates people to correct injustice. Can we say that this is where the tragic similarity between the Maidan and separatism manifested itself from the perspective of oppressed social groups? After all, in both cases, the involvement of many people in resistance was driven by a sense of injustice caused by the government’s deafness to societal demands and the disproportionate, indiscriminate violence in response to the protest.

The parallels here are obvious and are related to the reaction of defenseless civilians who, on the one hand, see the arbitrary violence of the security forces against the Euromaidan protesters. On the other, they see violence committed by the Ukrainian state in the form of the military, volunteer battalions, or irregular organizations against people who are advocating other causes. It should be emphasized here that in the spring of 2014, people who protested in various cities of Donetsk and Luhansk regions were already aware of the precedent set by the Maidan. The precedent was that protests should be perceived as a legitimate way of expressing one’s own judgments and opinions. And if they encounter opposition from the authorities, this demonstrates the illegitimacy of the authorities themselves. People were aware of this precedent set by the Maidan. On the one hand, the Maidan was right in the way it reacted to the arbitrary violence of the Berkut riot police towards peaceful protesters. On the other, the knowledge of how the Maidan reacted, namely by mobilizing and creating self-defense units and then using force, significantly accelerated the process of armed self-organization in Donbas.

Berkut police on the Maidan. Photo: from open sources

The model used on the Maidan was then appropriated by protesters who came out in Kramatorsk, Lysychansk, and Siverskodonetsk. And the emotional content of their reaction was certainly very similar. But in the case of Donbas, it was already reinforced by what they saw happening on the Maidan and by the realization of certain double standards that the new leaders of the Ukrainian state, that is, the leaders of the Maidan, applied on the one hand to peaceful protesters in Kyiv, and on the other hand to protesters in Donbas.

How did the post-Maidan Ukrainian government lose legitimacy among a certain part of the Donbas population? Was it a gradual process following Yanukovych’s escape and the events that followed? Or was there a specific breaking point and a point of no return, such as the announcement of the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO)?

The new Ukrainian government that came to power in Kyiv after the victory of the Maidan could not lose legitimacy in Donbas because it did not have it, which was the key problem. All the polls conducted in March and April 2014 showed that a significant number of citizens in Donbas, considerably more than in other regions of southeastern Ukraine, denied this government legitimacy. That is, they questioned the legitimacy of these people’s coming to power and their right to govern. Legitimacy is not only the legality of the government, but also the general recognition by citizens of the government’s right to govern. For these citizens, the victory of the Euromaidan was an illegal way for its leaders to come to power, as it was achieved through violence on the one hand and with the assistance of the West, namely the United States and the European Union, on the other. And the combination of these two factors—violence and direct support of the Maidan by Western powers—was the reason why a large part of the Donbas population rejected the new government’s legitimacy.

The key question was whether this legitimacy crisis could be resolved in any way. It could have been overcome through political measures that were not related to the military response to the events in Donbas but rather aimed at convincing a significant portion of citizens that their rights would be respected and upheld as they had been in previous years. For various reasons, this did not happen. The institutional mechanism that could have addressed this legitimacy crisis—namely, the presidential elections held at the end of May—was destroyed by the armed takeover of most of Donetsk and Luhansk regions. This mechanism could not be used.

But the key obstacle to overcoming the legitimacy crisis was undoubtedly the launch of the ATO. And the way the ATO was launched. The essence of the problem was that the new government, which had not yet gained legitimacy in Donbas, was already sending troops to Donbas to suppress protests and stop armed militants, whom many in Donbas perceived as their defenders. This decision has undoubtedly exacerbated the crisis instead of resolving it.

Why did the city become a convenient environment for Russian militants to quickly establish control, as suggested by the title of your book Seize the City, Undo the State? How did this happen? Often, when we think of successful uprisings, we imagine insurgents in remote villages, but in this case, we are dealing with militants operating in cities.

Yes, not only in villages but often in the mountains. Ukraine has quite a good experience of guerrilla warfare in the mountains. I write that many civil war scholars have emphasized for decades certain advantages that rural areas or areas remote from the capital in mountainous areas offer to insurgents in asymmetric warfare.

The idea that insurgents can use cities in armed conflict as a kind of shield has emerged in the last 15 years. The term “Urban Insurgency Campaigns” has emerged, which refers to cases of successful insurgencies or armed conflicts when cities become centers of insurgent activity. The main advantages that insurgents gain by staying in cities are related to the difficulty of liberating them, as such liberation will involve a significant number of civilian casualties.

The Ukrainian military command quickly realized this when they surrounded the Sloviansk–Kramatorsk conurbation. For a very long time, they could not enter the city proper, because entering the city implied a likely large number of civilian casualties, because then any civilian could be perceived as a potential threat. And this is the second feature of a military campaign in an urban environment—the ease with which insurgents either take on the appearance of or transform into civilians, thereby disappearing into the civilian population and complicating the process of identifying and eliminating individual pockets of armed resistance.

The choice of Sloviansk as the center of the armed uprising was extremely sound and logical from a strategic perspective. The foundation of the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics (DPR and LPR) was laid by the seizure of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) building in Luhansk and the regional state administration in Donetsk, followed by the swift proclamation of “people’s republics” by those who had taken over these buildings. The problem for the separatists, however, was that their so-called republics initially controlled nothing beyond these two buildings. They lacked actual territorial control over administrative units within Donetsk and Luhansk regions. The Ukrainian authorities quickly recognized this weakness. Only with the arrival of Igor Girkin (Strelkov) and his capture of Sloviansk did the separatists begin to establish broader territorial control.

Barricades around the Donetsk Regional State Administration and banners with anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western slogans, April 15, 2014. Photo: Andriy Butko

Importantly, this seizure did not begin with cities close to the Russian border in Donetsk and Luhansk regions, but rather with one of the most distant cities from the Russian border. On the one hand, it was easy for pro-Russian forces to establish control near the Russian border even without Girkin’s presence. On the other, if the uprisings had been limited to border areas, the Ukrainian authorities could have swiftly restored control over a significant part of Donbas. When we saw that Sloviansk, which is very close to Kharkiv region, was captured, it became clear that the entire part of Donetsk region beyond Sloviansk was de facto falling under separatist control. To get to Donetsk, you first have to go through the Sloviansk–Kramatorsk conurbation. That is, with this step they cut off a significant part of Donetsk and then Luhansk regions because they simultaneously began to seize the Lysychansk–Siverskodonetsk conurbation, cutting off a significant part of Donbas from the access of the Ukrainian authorities. That is, it was a very good tactical and strategic move because it allowed the militants to expand their territorial control over the rest of Donbas.

When Girkin arrived in Sloviansk, he was met by pro-Russian activists and self-defense units created earlier. What kind of relationship developed between Girkin and these activists and self-defense members? Do they seamlessly join Girkin’s unit, or does he push them into the background?

This relationship can be described as primarily a relationship between a patron and his clients. The patron was undoubtedly Girkin himself. The clients were those individuals from the local population who initially expressed support for him, starting with Girkin’s appointment of the self-proclaimed people’s mayor of Sloviansk, Vyacheslav Ponomarev, and many other local civilians who supported the Russian agents who came and seized the Sloviansk–Kramatorsk conurbation. These relationships were based on the realization of the benefits that these local civilians provided to the Russian military.

Pro-Russia supporters in Sloviansk greet a group of militants from Russia led by Igor Strelkov (Girkin) — in front of the already captured city police department, April 12, 2014. Photo: Gleb Garanich / Reuters.

What was this benefit? It was that they created the impression of internal support and that these were not just guys from Crimea or from Russia, but it was actually a combination of local and foreign rebels. And giving people like Ponomarev or Gennady Kim in Kramatorsk some administrative powers gave the impression that power was in the hands of the locals. This idea was communicated both to the locals and to the outside world in Ukraine and beyond. Ponomarev gave press conferences and spoke to international journalists, presenting himself as the self-proclaimed mayor of Sloviansk.

They were absolutely controlled administrators because, in fact, the power was in the hands of the so-called city commandants. And these city commandants, for example, in Horlivka, Kramatorsk, and Sloviansk, were connected to the Russian special services. Most of them were retired, that is, inactive officers of the special services, but they undoubtedly had a direct connection with Moscow. And then, as events unfolded, as I show in the book, some of the locals who were politically involved with the beginning of the separatist movement, such as representatives of the Communist Party of Ukraine, were gradually removed from decision-making.

The key event that led to the decline in the value of local cadres was the referendum on May 11, 2014. The process of organizing the referendum required a significant amount of technical and administrative knowledge, which only local elites and activists could provide. I demonstrate that in most cities, the referendum was organized either by city council deputies or by the heads of city council executive committees, who had access to ballot boxes, voter lists, and knew how to conduct elections. After the referendum, the importance of these individuals gradually began to diminish, and in effect, almost all power shifted entirely to the military.

At the same time, the administrators remain important in the sense that the very process of administering these cities, namely maintaining access to city funding, funding for public transportation, paying salaries and pensions, all required support and connections with Kyiv.

An election billboard about the referendum in Donetsk, May 8, 2014. Photo: Andriy Butko

After reading your book, it seems that the Donbas branches of the Communist Party of Ukraine almost unanimously supported the separatist movement, unlike the Party of Regions, where there was a split. Why did the Donbas Communists[1], as a single political force, decide to support the separatist movement?

The answer lies both in the ideological plane and in certain political features of the Communist Party and the Party of Regions. The Communist Party, especially its local cadres in different cities of Donbas, was formed primarily by ideologically motivated activists who had little material interest in politics. The Communist Party’s ideological beliefs were linked to the notion that the Soviet Union should be resurrected in some form. And Ukraine's affiliation with Russia should not be questioned but reinforced. So, when the pro-Russian protests began, it was perceived by many ideological activists as the beginning of restoring the former unity of brotherly nations.

The Party of Regions, in contrast, was not monolithic. It did not have the clear ideological guidelines that the Communists had. And a significant number of local deputies, leaders and activists of this party joined it primarily out of opportunistic calculations related to certain material and career benefits that membership in this party entailed. So, when the armed uprising began, which created risks for many of these people, they had no desire to sacrifice or take risks for the sake of certain political ideals.

Although there were some cases, particularly among businessmen, who provided financial support to the separatists—as seen in Donetsk, for example—these instances were not as widespread as they were within the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU). They often depended on specific individuals—their calculations and perceptions of their future. This is because the Party of Regions functioned as a broad umbrella organization that included a large number of people with completely different political views—or, in some cases, no political views at all. For this reason, the ideas of “Russian Spring” did not resonate with them ideologically.

Local elites, namely city mayors and deputies, always reacted to the actions of pro-Russian activists or Russian agents but never acted proactively. Moreover, they did not even coordinate their actions. For example, you note that although Lysychansk and Siverskodonetsk were located nearby, the mayors of both cities did not communicate with each other in any way. Why did this happen? Why did the connections within the Party of Regions, to which almost the entire local elite belonged, fail to help develop a coordinated strategy in the spring of 2014?

Mostly it has to do with the way this bureaucratic elite functioned over the previous decade, since 2004, when this power vertical of the Party of Regions was formed. As it was explained to me on several occasions, there were meetings in Donetsk or Luhansk with the regional leadership that represented the interests of the Kyiv leadership. This regional leadership of the Party of Regions gave clear instructions and explained what the various mayors had to do and how they had to act. They received these instructions from the Party of Regions headquarters in Kyiv. Moreover, there were personal patronage relationships that were established between individual heads of the Party of Regions in the cities and certain business or political patrons of the Party of Regions. For example, in Rubizhne, Siverskodonetsk and Lysychansk, Yuriy Boyko was particularly influential due to his business assets there. Another part of Luhansk region—for instance, Starobilsk—was under the control of Oleksandr Yefremov. In Donetsk region, Rinat Akhmetov was extremely influential.

This patronage structure thus consisted of two parts. On the one hand, there was a formal administrative system of instructions that went from top to bottom through the Party of Regions hierarchy. On the other hand, there was a system of control through informal relationships between individual patronage figures and their clientele in individual cities. First, the events on the Maidan and then Yanukovych’s escape broke both systems of control. The Party of Regions ceased to exist from the end of February 2014 and split into three or four different subgroups that were primarily interested in maintaining their own security and their own fortunes. They were not interested in what was happening in Donetsk and Luhansk regions, especially in small towns. However, informal relations continued to exist. For example, Akhmetov maintained control over the members of the city council in Mariupol. And Yefremov had some influence on the events in Starobilsk. However, given the unpredictability of the events that were unfolding rapidly in these areas, it was difficult to give any clear instructions without understanding where the process was headed.

It is easy to trace the uncertainty and confusion these patronage figures felt through the example of Rinat Akhmetov in Mariupol. There were several moments when, on the one hand, figures associated with Akhmetov—the directors of the largest enterprises, Azovstal and Illich Steel and Iron Works—directly interacted with separatist militants in Mariupol and signed various declarations with them. This happened at a time when Akhmetov felt weak and sensed that the situation was developing in Russia’s favor, especially after the clashes on May 9 in Mariupol. On the other hand, when it became clear that the separatists in Mariupol did not have broad support or significant military potential, Akhmetov radically changed his position. He began doing everything possible to eliminate the separatist movement—both from within Mariupol, through the directors of his enterprises, and from outside, with the help of the Azov battalion and other volunteer battalions.

Rinat Akhmetov. Photo: Bernd von Jutrczenka / dpa

We can see that the fluctuations of these patronage figures and their uncertainty did not allow them to control their representatives in different cities with the same confidence and as clearly. This unbalanced the coordinated system and created a sense of chaos among the leaders of these cities themselves. Many of these cities in Donetsk and Luhansk regions were run by people who had been in office for a very long time. That is, many of these cities turned into personal fiefdoms of these leaders. For example, the city of Bakhmut had been run by Oleksiy Reva since the early 1990s. Although they were embedded in these patronage-client relations within the Party of Regions, they built their own system of control over these cities, where they were the actual patrons. So, at the moment of the collapse of external control, these people were primarily concerned with preserving their own wealth in these cities and their own control over the clientele that they had developed in these cities. So, there was no direct interaction or coordination, because each of them had their own interests that they were pursuing at that moment.

You identify several strategies for city mayors when separatists proclaimed their authority and often used force to assert it: collaboration, refusal to take a clear position, sabotage, flight, or resistance. You also show that these strategies could change depending on the circumstances. Could you explain what influenced the choice of a particular strategy? Was it their own beliefs? Or were there other considerations? And why did the strategy change depending on the circumstances?

During the protest days in February 2014, a large part of these local elites contributed to the formation of self-defense units, which later became the basis for the formation of the so-called militia in Donbas. They did so in response to instructions from above, but they nevertheless contributed to the formation of these self-defense units. When they realized that the new government in Kyiv had stabilized despite the annexation of Crimea—and that destabilization following the example of Crimea could create additional threats to them personally and to their government, as some local activists demanded that the local leadership be replaced as well—they changed their behavior.

In March, they started using the rhetoric of reconciliation with Kyiv and emphasizing the need to avoid further escalation. I tracked this by analyzing articles in local newspapers and using official videos of speeches at meetings of executive committees, city councils, and press conferences of the leaders of these cities, which I found in open sources. So, it is well documented in my book. For me, this change in rhetoric indicated that a significant number of local leaders were ready to accept the new government and act in the new political realities. This choice also indicated to me that a large part of the local leaders did not have any strong pro-Russian ideological beliefs.

So, when the armed escalation began in April, their actions were primarily driven not by their political or ideological beliefs, but by their sense of how much these armed groups posed a threat to them personally. In cases where cities, such as Kramatorsk or Lyman, were captured or had a significant presence of armed militants, local elites were quick to collaborate or were ready for some form of cooperation. In Kramatorsk, there was no collaboration, but there was a willingness to cooperate partially, which I call in English hedging, that is, betting on both sides. There was direct collaboration in other cities, such as in Lyman or Toretsk.

Why was there a different reaction? It’s hard for me to say exactly why in some cases we saw collaboration and in others just hedging or some form of cooperation. I don’t answer this question in my book, but perhaps the answer lies in how close the militants themselves were to the leadership of these cities. In the case of Druzhkivka, the mayor, Valeriy Hnatenko, had his clientele among the militants who were operating in the city at the time. These were his old friends and business partners. And when you realize as a leader that people who have weapons are to some extent accountable to you, it is much easier for you to take more radical steps in cooperation with the separatists. In Kramatorsk, when Mayor Kostyukov had no connection to the armed people in the city, he agreed to certain forms of cooperation with them, for instance, in organizing a referendum. However, Kostyukov did not go for open collaboration, in contrast to the mayor of Druzhkivka, who provided direct ideological and political support to the newly formed separatist groups.

Speaking about the failures of the separatists to establish their control, you point to the importance of the use or threat of violence by pro-Ukrainian activists. Does it mean that only firm resistance could have preserved Ukrainian control over the entire Donbas? Could a harsher response from Kyiv have led to greater mobilization of anti-Ukrainian sentiment and even a faster direct intervention by Russia? Or is this more about resistance at the regional and municipal levels rather than from Kyiv?

Resistance to establishing separatist control over cities was successful when there was a combination of two factors. First, when there was a certain proximity of the Armed Forces of Ukraine or volunteer battalions. They were not directly present in these cities and thus did not contribute to antagonism with the local population. In the case of Pokrovsk, the volunteer battalions were stationed outside the city. However, their implicit presence strengthened and convinced those pro-Ukrainian activists that they had military support if threatened.

Secondly, the ability to coordinate pro-Ukrainian activists, either by local elites or by representatives of administrative elites from other regions, was important. In the case of Svatove, which is a case of successful resistance to the seizure of the city, the key role was played by the mayor Yevhen Rybalko and part of the local business elite, primarily large landowners. On the other hand, in the case of Dobropillia, we see that a crucial role in coordinating local Ukrainian activists and creating a local pro-Ukrainian self-defense unit was played by Dnipro elites, Valeriy Kolomoisky and Hennadii Korban, who provided sustained support.

In many cities that were more distant from Sloviansk and to which neither Girkin nor Bezler had easy access, the number of separatists and militants was quite small, and pro-Ukrainian activists could quickly organize themselves and use force against the separatists. When I talk about force, I am not talking about killing them but about forceful influence. There were cases when these pro-Russian activists were captured, interrogated, intimidated, and then released. And a significant number of these people who went through this process simply left the city for other cities. These simple steps helped to neutralize the threat of spreading support for separatism in the city itself.

Former leader of the separatists in the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic, Igor Strelkov (Girkin), with his guards near the Donetsk city administration building, July 10, 2014. Photo: from open sources

The main mistake was to create external pressure. For example, there were attempts to change the situation in the Sloviansk–Kramatorsk conurbation by using force from outside and mobilizing people from other regions of Ukraine, instead of creating resistance within these cities among the supporters of Ukraine, whose numbers were sufficient. From my research, it became clear that enough people in the region were ready to support Ukraine, but they did not feel safe since April 2014. So, a significant part of them had to either leave these cities or stop being active. If there had been attempts to support these people and create centers of resistance with their participation, perhaps the situation would have developed in a completely different scenario.

You conducted your field research in 2018–2019, a time when there was still hope for a peaceful resolution of the conflict in Donbas and differing perspectives on the events of spring 2014 in Ukraine. When you spoke with local residents, how did they respond to your questions? What emotions or biases did they express? What do you recall most vividly from those conversations?

Both among those who were pro-Ukrainian activists, i.e., in favor of the unity of the state, or members of opposition parties (for example, the Batkivshchyna party was highly visible in these cities), and among those who supported the pro-Russian protests in these cities, there was a sense of disappointment. The disappointment among pro-Ukrainian activists was that they felt that the Poroshenko government, and I did most of my research before Zelensky became president, had pissed them off and did not use those 3–4 years to punish and purge the local authorities. They believed that even at that time, in 2018–2019, most of the people who supported the creation of D/LPR among the local authorities remained in their positions. The most frequent accusation against Poroshenko that I heard from pro-Ukrainian activists at the time was that all the law enforcement agencies, the SBU, the Prosecutor General’s Office, to whom they provided information about these collaborators, ignored this information. If it was used, it was to blackmail local officials and ensure their loyalty to Petro Poroshenko personally. And I felt deja vu when I moved from one city to another and talked to pro-Ukrainian activists, because the set of claims against Poroshenko’s government was very similar. And people spoke emotionally. This was also a revelation to me, because it was always believed that Poroshenko, who was already running for a second term under the slogans of patriotic revival and the fundamental establishment of Ukrainianness, was perceived as a person who was trying to forcefully establish Ukrainian power. And here we see a completely different reaction from people who live in Donbas and say that he is actually rewarding former collaborators.

As for those people who supported the D/LPR, many of them felt similarly disappointed. Many were already outside of Ukraine, and I interviewed them via Zoom. They felt disappointed with the way Putin had acted in the Minsk process. They felt that Putin had betrayed them and the D/LPR by not taking more radical steps. Firstly, he did not annex the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, and secondly, he did not establish Russian control over the entire territory of Donbas. It seems to me that one of the reasons why they told me the details of their activities, the decisions they had made at that time, and their reasons and motives was because they felt that no changes would happen. They felt that they would not see a more radical reaction from Putin. The region’s gradual decline would persist, and the Minsk process would continue indefinitely.

These were two mirror worlds. Some were disappointed with the new Ukrainian government, while others were disappointed with the old Russian president. Four or five years after the conflict started, we managed to reflect on what had happened and realize that this process had reached a dead end. So, when you asked about peace initiatives or attempts, most people were convinced that peace would be impossible to achieve and that the conflict would smolder and remain the same.

The full-scale invasion of 2022 was an opportunity to rethink 2014. How can we talk about 2014 from the perspective of 2025? What narratives and ways of talking about 2014 seem appropriate to you? Why should we talk about 2014 today?

I believe that in 2025, even those who experienced 2014 as adults may find many of the reactions, perceptions, assumptions, and judgments expressed in 2014 to feel entirely foreign and incomprehensible today. This is because, over the past three years, Ukraine has gone through an emotional and political transformation that other countries typically experience over many decades. In this sense, 2014 may seem like something that happened a hundred years ago. However, this carries certain risks and threats. We may misinterpret what happened in 2014 because we will be looking at those events with the knowledge of 2022. As a result, we might forget the driving forces behind the process that led to the formation of the two unrecognized republics, which later became the foundation for a new wave of Russian aggression. That is why my book deliberately includes many direct quotes from participants on both sides, excerpts from speeches at rallies by those who supported the pro-Russian protests, as well as statements and interviews from local leaders and political elites. By reconstructing these perspectives in my book, I aim to ensure that we do not forget how multidimensional this process was and how differently political events were perceived in various parts of Ukraine—and even within Donbas itself.

Over the past three years, we—and especially many Western researchers—have had the impression that we in Ukraine are united in how we perceive Russia and the West and how we see our future. And especially Western researchers who are just starting to study Ukraine or have studied it only for the last 5 years may mistakenly project this sense of unity onto the period of 2004–2014. I experienced that period firsthand—as a student, a doctoral candidate, and later as a young researcher and citizen of Ukraine. I personally observed and participated in the historical events leading up to 2014. The main goal of this book is to record and preserve the complexity of the processes that took place in Ukraine, challenging one-sided interpretations.

Footnotes

- ^ The Communist Party of Ukraine leadership expelled those members who supported the separatist uprising. Local communists formed the Communist Party of Donetsk People's Republic, but the DPR authorities banned them from participating in the elections.

Talked to Serhiy: Iaroslav Kovalchuk

Translation from Ukrainian: Pavlo Shopin

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva