On 6 July this year, a tragic incident happened at a construction site in Kyiv. According to one version of events, a tower crane operator a construction site in the northwest of the city - a young father who loved his profession - took his own life. Apparently, he jumped out of the crane cabin window 16 stories up after discovering his wife had cheated on him.

Commenting on those rumours, his manager said: “He worked for our company for eight years. A normal, reasonable man took his own life. I don’t know why people decide to do this. Whether he had some unpayable debt or something like that, I haven’t heard anything about that. We have a good company: no one had a problem with the man who died. The only thing I know is that the day he died, he rang his family and friends and asked them to forgive him, he said that he’d done irreversible on social media. It’s impossible to fall out of that kind of crane by accident.”

Ukraine’s crane operators trade union is sceptical of this interpretation. “Unscrupulous employers are often ready to deploy the most despicable tactics in order not to lose money. This is why we’re looking at different versions of how the crane operator died: we’re trying to separate the testimony of people who worked with the man who died from rumours and information they’ve heard from representatives of the owners and the subcontractor.”

For property developers in Ukraine, when an accident takes place on site, transferring responsibility to the workers is not an uncommon move. For example, after the death of crane operator Lida Hurina at a construction site on Kyiv’s left bank in 2014, her employer openly lied about her being “a bad worker” and “untidy”. Yet according to her colleagues at other companies, Hurina was a model employee.

Unfortunately, since 2014, the rate of workplace deaths in Ukraine has continued to deteriorate. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of workplace deaths in Ukraine rose by 13%.

According to the first voluntary national review of sustainable development goals in Ukraine, progress in guaranteeing reliable and safe working conditions is either absent or extremely weak. The main factors behind workplace accidents include: not following workplace safety instructions, management obligations not being met, and violation of transport safety and technical instructions.

To assume that workers who suffer accidents are “not sufficiently informed” about the risks to their health would be naive. Ukraine lacks a functioning institution that can respond to violations of labour rights. Almost all of Ukraine’s state supervisory bodies have been reorganised into the state labour inspectorate, whose powers are gradually being eroded under the pressure of the business lobby.

Instead of supervising and monitoring Ukrainian employers’ activities, the state labour inspectorate now spends its time consulting and explaining. At times, this can verge on the absurd. For example, an employee reports a labour rights violation, and in response the labour inspectorate calls up the employer and asks them to sort the situation out. After being notified, the employer can “sort out” the employee, rather than the violation. And meanwhile, the inspectorate recommends employees whose rights are being violated that they should “work legally”. Potentially up to 30% of Ukraine’s working population are involved in informal labour.

Since the start of quarantine in Ukraine, certain state services have succeeded in increasing their effectiveness online, but some work is impossible to do digitally. For instance, to sign on as unemployed has become easier. Prior to quarantine, official statistics suggested there were 100,000 jobs for 300,000 unemployed persons in Ukraine. After quarantine kicked in, 500,000 unemployed persons have had to compete for 60,000 jobs. Hence why the labour inspectorate’s advice (“Don’t work in the shadow economy”) has not been put into practice.

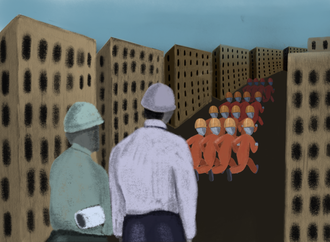

Kyiv, 2019: A construction worker hammers in nails without a safety harness over a 25-storey drop | (c) Aleksei Arunyan

Protecting labour rights at Ukraine’s construction sites has become more difficult. First, in March, Ukraine’s state architectural and construction inspectorate was closed down for good. At the time of writing, eight people currently work at its replacement, the state construction inspectorate. Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers has declared that this new inspectorate has started work, but it’s not true: in June 2020, you couldn’t write to the new inspectorate - all correspondence was returned to the sender. It seems in these five months, you can build what you want, how you want.

Second, for five months now Ukraine’s labour inspectorate (and the construction inspectorate in April) has been reacting to reports of labour rights violations with boilerplate answers, claiming site inspections are impossible due to the quarantine. This limits the space for defending labour rights legally. On the one hand, Ukrainian ministers, MPs and public officials have been visiting restaurants and cafes during the pandemic. And on the other, they have essentially forbidden inspections of these workplaces for undeclared work. For the fifth month in a row, the people who bring our public officials food, drive them around the city, deliver goods and offer other services have been unable to legally defend their workplace rights.

Covid-19 has intensified the abusive actions of bad faith employers, and made the fight for improving workplace conditions harder. Of course, Ukraine’s architecture and construction inspectorate was closed down before quarantine measures came in place, and the state labour inspectorate simply “forgot” to add a section on workplace accidents to its new website. The inspectorate no longer publishes daily statistics on workplace accidents, it now only issues them on request.

There have been no inspections these past five months - you can stop paying your employees, or you can find people who will, due to unemployment, work for empty promises of future payment.

On occasion, businessmen make remarks that left-wing and trade union activists “demonise” employers in Ukraine. “Yes, we do demonise businessmen sometimes,” said Antonio dos Santos, an ILO representative in Ukraine, during a recent online course. “But if we didn’t have to deal with these incidents from time to time, then there would be nothing to discuss.”

Under capitalism, paying for the funeral of one or two workers is just another line in a company’s budget. The dead are driven back to their families, and the businessmen’s bank accounts keep ticking over.

Translated English by openDemocracy