Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine since February 2022, as well as both national and international policies to deal with the impact of the war, have surely influenced the spaces and networks of social reproduction, both in Ukraine and in refuge. The destruction and resulting displacement, neoliberal austerity, unprecedented border regulations, and refugee policies, have all led to a reconfiguration of social reproduction in Ukrainian society.

But to really understand what is happening, we need to look closer at the processes and relations of social reproduction in Ukraine over the recent years. How have the policies pursued since 2014 influenced the public infrastructure of social reproduction? What has the impact of war been, and how does social reproduction adapt to these new realities? What are informal networks doing to stitch together the gaps created by destruction and displacement, both before and after the full-scale invasion? And what processes are shaping the potential future of social reproduction in Ukraine?

It should be noted that in this article I predominantly analyse the dynamics in public care infrastructure, though private actors (both for-profit and nonprofit) also play their role. However, there is little data available on private actors and additional research is needed to evaluate developments in private care infrastructure. Besides, public care infrastructure is (and should be) the most universal structure to socialise care. Hence, the most attention in this article is paid to public education, healthcare and elderly care institutions. One can note that there are also other increasingly (in the context of war) important parts of public care infrastructure, for example, infrastructure for children and adults with disabilities. Developments in this segment require further research.

Social reproduction and its embeddedness

Within Marxist Feminism, social reproduction is defined as both the biological reproduction of human species (including its environment) and the reproduction of individual labour power as a commodity[1]. As Lise Vogel outlined, the reproduction of labour power in a class-based society encompasses both the reproduction of the human ability to work, and sustaining those from the working classes who are (yet or already) not able to work[2].

Within different theoretical frames, social reproduction may include biological reproduction, sexual and emotional or affective duties, reproduction of culture and ideology[3]. Here, we shall focus on that part of social reproduction which encompasses biological or labour power reproduction and in which housework and care labour play crucial role. Though it essentially depends on the sphere of production, it is also to various extent supported by charity, personal networks, the state, unwaged reproductive labour, subsistence agriculture etc[4].

Illustrative image

Social reproduction is embedded in various formal and informal networks as well as institutions, especially those performing a share of care labour. Care infrastructure is spatially fixed, heavily conditioned by state policies and external circumstances, and therefore dependent on interventions and sensitive to interruptions. At the same time, since social reproduction is largely about the reproduction of life itself (pushed by ‘the worker’s drives for self-preservation and propagation’[5]), and in varying degrees relies on informal networks, it is relatively ‘adaptive’. This embeddedness in infrastructure and networks is crucial to understanding social reproduction in the context of austerity policies and war.

The ‘optimisation’ of care infrastructure before 2014

Though neoliberal austerity policies of Ukrainian government were crystalized and consolidated after 2014 during Petro Poroshenko presidency and continued after Volodymyr Zelenskyy was elected in 2019[6], the ground for public infrastructure cuts was laid down during Viktor Yushchenko’s term and had been actively going on already during Viktor Yanukovych presidency (2010-2014). The cuts were developed under the logic of ‘optimisation’: in this logic, the economic argument of efficient expenditures is prioritised over access to care infrastructure as a social right. Hence, a public facility is considered useful enough only if it provides ‘services’ to a substantial number of people.

In the process of ‘optimisation’, between 2005 and 2013 the number of rural schools decreased by 11.7 percent[7]. During the same period, the number of places in pre-school educational institutions (nurseries and kindergartens) was in fact relatively stagnant and the proportion of children covered by this infrastructure even increased. Still, in 2013 only 41 percent of children aged 3-6 in rural areas were covered by pre-school educational institutions[8]. Moreover, there were almost no public care institutions for children before the age of two years, and a very limited number of places for children between the ages of two and three — in 2013 only around fifteen percent of children aged 0-2 were attending public care institutions.

Between 2005 and 2013, the number of hospitals in rural areas decreased by 70 percent[9]. There is less well-established data for elderly care institutions[10], but the overview suggests that there was no substantial decrease in this infrastructure during that period. However, the number of public elderly care facilities was extremely low anyway — for example, in 2010 there were only 50,000 places for adults in the boarding houses of various types (including those for elderly people)[11], while the estimated population aged 65+ was almost 7 million. It is important to keep in mind that a substantial part of the elderly care was performed by social workers of the social service centers in the form of visiting care. However, public visiting care covers different categories of people and there are no separate statistics on how many elderly people were covered by this public service before 2014. According to available data[12], the number of the general population, who received various kinds of social services and assistance from social services centres, increased from 1,51 million by roughly 90,000 (6%) between 2010 and 2013. At the same time, the number of “detected”[13] elderly people, who needed social services and assistance increased by almost 160,000 (11%) between 2011 and 2013, and in 2013 5.4 million elderly people needed visiting care.

Illustrative image

Though some additional measures were supposed to be taken for those who lose access to care when a facility (predominantly in rural areas) was closed — such as school or kindergarten buses — this often didn’t work as intended. For example, there could be periods when buses were out of operation either due to lack of fuel or snowy winters blocking the roads in rural areas; sometimes in winter, a rural school could be closed for several weeks because there was no money for heating.

The described ‘optimization’ of the public care infrastructure, justified by the motto of efficiency, decreased many families’ access to the various forms of care support, especially in rural areas. Consolidated around the idea of market logic, this track of ‘optimization’ continued in the following years.

Neoliberal austerity after 2014: an overview

Starting from 2014 — with Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the start of the war in Eastern Ukraine, political changes, economic crisis[14] and conditionalities imposed by creditors[15] — cuts in public care infrastructure continued under a new neoliberal frame. Partially following the logic of ‘optimization’ from the previous years, these measures were first justified by the neoliberal austerity in response to the financial crisis. However, soon they were consolidated, no longer presented as temporary or emergency changes but as holistic reforms of the sectors concerned — i.e. education, healthcare, and social services.

After 2014, the motto of the reforms in these sectors was ‘money following people’, meaning that it is not that public infrastructure should be financed by the authorities, but rather that authorities should buy ‘services’ from different providers to satisfy the population’s needs. The term ‘service’ (healthcare service, educational service, social service etc.) was not much widespread in Ukrainian public and political discourse before the launch of the mentioned reforms. Presented as a better frame to suit a ‘European’ society, it has come to signal the two principles at the core of the reform: market logic and departure from universalism[16]. Services can be provided by anybody who corresponds to some established standards, and authorities only play the role of buyers, promoting competition between providers. Services are not universal social rights: authorities may buy them or not, depending on the available budget and priorities of its distribution.

The counter-crisis austerity measures were presented as necessary, unavoidable, technical and apolitical measures, but later also as ‘reforms’, praised in mainstream discussions. But in terms of population’s access to care infrastructure they had relatively similar outcomes to those of the previous ‘optimisation’. 14 percent of schools, i.e. 2,498 in total were closed between 2014 and 2019[17]; 2,281 of these were rural schools, meaning that 19 percent of all rural schools were closed during this period. There was no such big reduction in pre-school facilities as their coverage of children aged 3-6 fluctuated between 71 percent in 2013 and 68 percent in 2019[18] (40-43 percent in rural areas). However, in the case of rural kindergartens, lack of funding from the local authorities could create the situation when a kindergarten operated only half of a working day or when a bus to a nearby kindergarten only went one way — making it hard for parents, who necessarily accompanied small children, to get back home. At the same time, pre-school facilities in big cities were often overcrowded: in some cases there were twice as many children in a group than regulations prescribed. Moreover, in 2019 coverage of children from the age group 0-2 by public care institutions stood at 16.5 percent – barely half the EU average.

Between 2014 and the end of 2016, 39 percent of hospitals and 21 percent of polyclinics were closed in villages[19]. The active reorganization of the healthcare sector makes it hard to compare later years — as some types of facilities were renamed, merged and reorganized. Taking this into account, it can be cautiously noted, that according to the information from the Ministry of Healthcare[20], there were only 20 hospitals left in rural areas in 2021, meaning the closure of 81 percent of facilities since 2014. The number of paramedics and midwives’ stations — one of the key healthcare institutions in smaller settlements — which were not actively closed in 2014-2016, was 8,708 in 2021, meaning a 34 percent fall since 2016. At the same time, there was a fivefold increase in the number of rural medical clinics between 2014 and 2021, which probably compensated for cuts in other facilities, taking on their functions[21].

Illustrative image. Artist: Gracia Lam

According to available data[22], the number of “detected”elderly people, who needed social services or assistance, decreased to almost 900,000, by almost half a million (33%) between 2014 and 2020. During the same period, the number of “detected” elderly who needed visiting care decreased by over 160,000 (34%), to 328,000 in 2020. At the same time, the number of the general population who received social services and assistance from social services centres decreased by over 400,000 (30%). It is important to keep in mind that after 2014 the Ukrainian government lost control over part of the territory, but this does not explain the dynamics fully. While most of the territorial losses of that period happened before 2016, the biggest relative decrease of people who received social services and assistance from social services centres happened in 2019-2020 – by almost 12%[23]. And the only available data on elderly people shows the decrease by almost 120,000 (13%) between 2019 and 2020. Hence, there clearly was a decrease in coverage of elderly population by social services.

As for residential elderly care, in 2020[24] there were approximately 43,000 places for adults in public boarding houses of various types (including those for elderly people), accommodating a little under 20,000 pension-age people, while there were already over 7.1 million people aged 65+. Conditions in the public boarding houses, where elderly are staying, sometimes attract public attention. They are reported by journalists and so-called human rights ‘monitors’ — a joint ‘National preventive mechanism’ created by authorities and civic activists, meant to be granted access to places of restricted freedom (including boarding houses). Various violations and bad conditions are reported almost ubiquitously, in some instances labelled ‘cases of cruel treatment, or humiliation that degrades human dignity’[25]. In such a situation, it is not surprising that according to the survey from 2014[26], only 3 percent of elderly people in Ukraine considered a boarding house to be the best option for a person if she cannot take care of herself anymore; 40 percent agreed that being placed in a boarding house is the worst thing that can happen to a person in her last years of life.

Multiplying crises: the impact of reforms, war and the COVID-19 pandemic

All these changes in public care infrastructure have not only influenced families’ access to care assistance, and through it the situation of women and gender inequality in Ukraine[27]. They have also influenced gender inequality in another way: leading to job cuts in these predominantly female public sectors of economy — though often low and extremely low paid, but relatively protected from informality and with legally adequate social packages. In the process of the reforms, their wages (often close to the minimum wage) as well as their working conditions hardly attracted attention of the authorities. For example, in 2020 the average wage of a person working in pre-school education system[28] was UAH 5,241 or approximately €170 (after taxes): 35 percent higher than the minimum wage[29], but just 57 percent of the average wage in Ukraine, lower than in any OECD country.

One of the most emblematic recent reforms took place in the social service sector. Based on the new legislation, introduced in 2020, the reform was intended to continue the shift from a more universal to increasingly targeted social security system and to create a market in social services. At the same time, the reform pushed their funding almost totally onto local budgets and paid no attention whatsoever to the working conditions and (extremely low) wages of the sector’s predominantly female workforce[30]. The government hoped that the market would be flooded by private actors (coming out of the shadow economy), as well as by charities and NGOs. This would make it possible to continue substantial cuts in public infrastructure; but this scenario didn’t come true. For example, in 2022 among the organizations in the open registry of social service providers, 14 percent were charitable organizations, and only 4 percent private ones[31]. Almost 80 percent of the registered providers were public.

Illustrative image. Artist: Chris Silas Neal

The cancellation of social payments and subsidies has been spreading since 2014[32], even before the reform of the social service system — as part of the ‘counter-crisis’ measures. Some payments, like the subsidy to a parent for the first three years of childcare, were cancelled. Others have been ongoing through redesign into increasingly targeted payments: more criteria were added for a person to be eligible to receive it, benchmarks were raised[33]. Subsidy for a single parent (the mother — in the vast majority of cases) is exemplary in this regard. Before the radical austerity turn, it was a universal social payment, where the fact of raising one’s child without a partner was enough to get this (small) support from the state. Turning this payment into an increasingly targeted one resulted in a drop in the number of people receiving it, from half a million in 2016 to less than 120,000 in 2021[34].

All these cuts in public care infrastructure and social payments were happening against the backdrop of the annexation of Crimea and the war in Eastern Ukraine resulting in the wave of internal displacement. At the end of 2021[35], there were almost 1.5 million registered internally displaced persons (IDPs), largely concentrated in the Ukrainian controlled territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, the Kyiv city and region, and the Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhya and Odesa regions[36]. This population shift meant higher demand for care infrastructure in those regions, with additional challenges in villages and the territories close to the frontline. Even during the relative stagnation of fighting and after the stabilisation of the frontline, the latter became a geographical obstacle. Together with neoliberal policies it created a phenomenon of ‘infrastructural vulnerability’[37] — the fragmentation and degradation of public infrastructure in local communities, which was not and could not be solved by humanitarian relief (due to its inability to substitute the state and due to the internal structural problems of this system’s architecture).

The COVID-19 pandemic and related crisis created additional challenges for social reproduction in Ukrainian society. For several months Ukrainian families were totally deprived of public childcare options — preschool facilities and schools were shut down and hardly any additional support (be it infrastructural or material) was proposed by authorities. Though workers from educational facilities were supposed to get most of their wage for the lockdown months, they were often forced to take part of their paid annual leave or unpaid vacations while the facilities were closed. And though different premiums were introduced by the government for key-sector workers (like healthcare and social work) for taking additional risks and workload, the payment of these bonuses was not always consistent, and for social workers the payment of these bonuses were dependent on the capacities of the local budget[38]. In the end, the general population and workers in care and key infrastructure often had to individually get by[39], often with scant material and time resources.

At the same time, the pandemic led to increasing politicization of the problems in the healthcare sector, due to the grassroots movement of nurses, which started in late 2019. Triggered by the ongoing healthcare reform and its inability to deliver higher wages and better working conditions, the movement developed around a social media platform, uniting several tens of thousands of healthcare workers (predominantly nurses) and materialized in numerous street protests during the pandemic[40]. By the end of 2021, the movement pushed the government to increase basic wages in healthcare: for example, starting from January 2022 wages were supposed to be doubled for nurses[41]. However, in February 2022 Russia started the full-scale invasion and this wage increase became only a ‘recommended’ step.

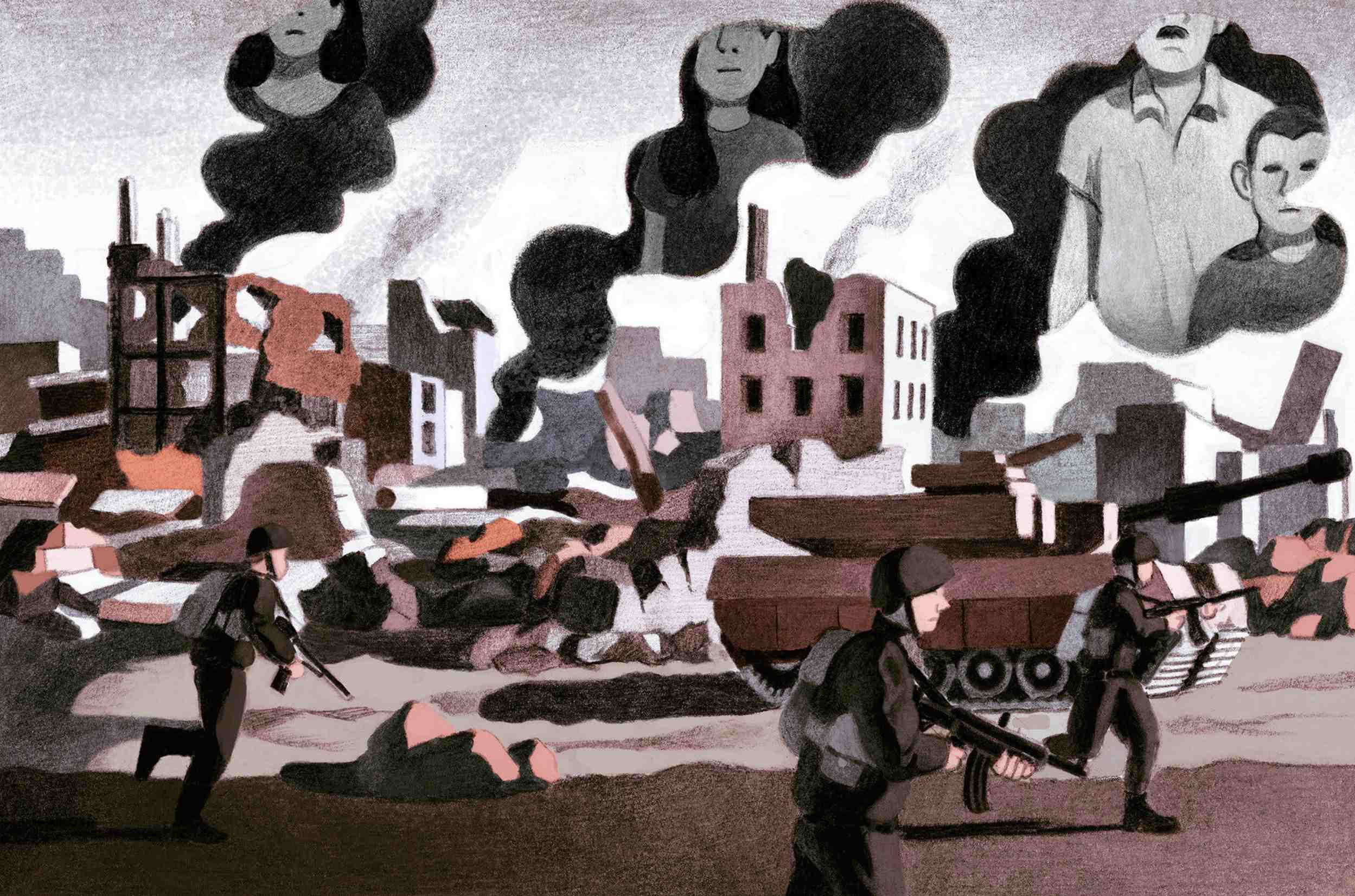

Destruction and institutional adaptation of care infrastructure after 24 February 2022

The infrastructure of social reproduction in Ukraine has suffered physical destruction since the beginning of war in 2014. This process has been extremely intensified following Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022. According to the official data, accumulated on the web portal ‘Education under threat’, 3,798 education institutions – schools, kindergartens, universities or orphanages – were bombed or shelled, 3,428 were damaged and 365 totally destroyed[42]. According to other official sources, 410 educational facilities were destroyed as of March 2023[43], including 116 pre-school facilities and 226 schools; every seventh school was damaged[44]. Though it is hard to establish a general number of educational institutions, i.e. in order to come up with the exact proportion destroyed, an approximate calculation[45] allows us to conclude that over 12 percent of educational infrastructure was either damaged or destroyed since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Illustrative image. Artist: Antoine Maillard

Not only direct hits stopped educational institutions from operating. Only those facilities, which had or could organize a shelter, which is usually just a basement, were allowed to continue their work — but in regions close to the frontline, even having a basement would not suffice (see the example of Kharkiv below). According to official data[46], in education year 2022-2023 only 56 percent of pre-school facilities operated offline (plus 15 percent in mixed format), while 29 percent worked remotely; only 34 percent of schools operated offline (plus 35 percent in mixed format), while 31 percent taught remotely. According to the Ministry of Education and Science, at the beginning of 2024 approximately 900,000 schoolchildren followed remote learning (either online or homeschooled)[47].

While it is obvious that pre-school educational facilities operating remotely will drastically diminish their role as care institutions, the case of schools is more complicated. As schools, especially primary and after-school programs, still play an important role in supporting childcare, the fact that they are working remotely also partially deprives families of care support. If an air alarm happens when a school or a kindergarten is supposed to open, a kindergarten won’t accept children until the alarm is over, while a school will resume its work after the alarm has ended, albeit sometimes in remote format (depending on local regulations). This makes it unpredictable each day whether and when a child will go into a facility.

The regulations on how educational institutions operate during the war are an example of institutional adaptation to wartime existence. They define which facilities can work, what the various scenarios are for their work in different conditions, and how this work should be organised. A separate example of these institutional adaptations comes from Kharkiv — a major regional centre just 30 kilometres from the border with Russia. This proximity sets the city within range of artillery (which almost cannot be intercepted) and under regular heavy attacks; for these reasons local authorities (as in many communities close to the frontline) did not allow schools to operate having only a basement as a shelter – rather, they had to have a proper shelter, which none of the local schools had. At the same time, Kharkiv is one of the few Ukrainian cities with an underground subway, which pushed the local authorities to make an unusual decision in September 2023, i.e. to open a school underground, in the technical rooms of the subway system. Over one thousand children get there by school buses from all over the city in approximately sixty classes (more than one-third of them are first graders), operating in two shifts. There is also information that one lyceum in Kharkiv has managed to build a proper shelter using funding from donors[48], and in spring 2024 local authorities opened the first underground school for approximately one thousand children (several more are planned). These are yet drops in the ocean and beyond the aforementioned options, local children can go to the now strongly growing number of private schools, which ignore regulations and operate without a proper shelter. The same is true of pre-school institutions in the city, although there are no public pre-school facilities underground.

As of November 2023, the Ministry of Healthcare reported[49] that 1,468 healthcare facilities were damaged and 193 totally destroyed. Hence, approximately 14 percent[50] of Ukrainian healthcare infrastructure was either destroyed or damaged after the beginning of the full-scale invasion. A peculiarity of healthcare facilities is their limited ability to operate remotely — which has a big negative influence on the actual care provided. At the same time, in many facilities it is close to impossible to move all the patients to a shelter when the air alarm starts. In this case, institutional adaptation has depended on particular territories and facility types. It has varied from evacuation of a facility to some safer location, the partial organisation of work in a shelter, and using sandbags and other precautions to minimize possible danger. To keep staff in territories close to the frontline, the Cabinet of Ministers introduced a bonus payment[51]. However, for junior medical staff this meant only 19-34 percent more than the extremely low minimum wage[52]. Moreover, considering that such bonuses were not fully paid during COVID-19 and other cases, it remains unclear whether they have been consistently delivered this time.

Illustrative image. Artist: Hanna Barczyk

Elderly care — visiting care by social workers, as well as public residential care — has also felt the consequences of war. At the beginning of the full-scale invasion people from boarding houses were not evacuated on time and some ended in occupation or under shelling; for many elderly people timely evacuation to a shelter was impossible; later evacuation imposed additional challenges on boarding houses in the receiving communities[53]. Multiple problems for elderly care were mentioned in the few thematic reports by international organisations[54]. Where families were separated — usually younger generations evacuated inside Ukraine or abroad, while some older people stayed behind — an additional workload was created for low-paid social workers providing visiting care close to the frontline, while their overall number declined. Given that most temporary shelters for IDPs were not accessible to some categories (people in wheelchairs, bedridden people), some families were also separated after evacuation, and elderly family members had to go to boarding houses. And while the topic of childcare and childcare infrastructure has been relatively actively discussed by authorities and media, problems of elderly care during (and before) the war are barely mentioned.

Stitching the gaps of care

That part of education and care which has fallen into the holes created by ‘optimisation’, cuts, neoliberal austerity, pandemic, war and occupation — as well as war-related institutional adaptation — has to be managed somehow, if social and individual reproduction are to be kept going. As elsewhere around the world, informal networks — nuclear and extended families, as well as personal networks beyond them — have been playing a crucial role in stitching the gaps of care in Ukraine, both before and after February 2022.

In Ukraine, as in many other societies, a disproportionate share of childcare within a nuclear family is performed by mothers, while women from the older generation of an extended family often take an active part in childcare, and women from the younger generation in elderly care. These are caused by the existing gender regime, which includes relatively traditional gender norms, as well as institutionalized and socio-economic inequalities. These care roles are manifested either to fully substitute often dysfunctional public and inaccessible private care facilities, or to cover time and functions, which are not covered by care infrastructure, or to ‘jump in’ when a force majeure happens. For example, according to a 2014 research[55], approximately 33 percent of women aged 60-64 regularly help with childcare and 43 percent do this from time to time[56].

The full-scale invasion in 2022 disturbed not only the functioning of public care infrastructure in Ukraine, but also led to mass population displacement, often breaking existing networks of care. In more specifically territorial-related cases, this applies to the situation of those under occupation, IDPs and refugees. But it also applies to the situation when a family member is killed or (a man, in the vast majority of cases) mobilised in the army.

The most large-scale break in the networks of care has befallen refugees, both due to their number (estimated as 6.4 million[57]) and the Ukrainian government’s unprecedented decision to restrict the cross-border mobility of men. The result is that 80 percent of adult Ukrainian refugees are women. Furthermore, according to research, 32 percent of Ukrainian refugee households consist of one adult — a woman in the vast majority of cases — with dependents, and 24 percent of two and more adults with dependents[58]. Hence, a situation of enforced single motherhood is widespread among Ukrainian refugees.

Illustrative image. Artist: Sally Deng

Ukrainian refugees with kids or other dependents are torn from their usual care infrastructure and networks. To continue managing care, they need not only integration into local care infrastructure but the informal connections they were deprived of due to displacement. Ukrainian labour migrants have often taken an active though unacknowledged role in supporting refugees’ social reproduction[59]. However, a close look reveals also other processes on the individual level. In order to get by, Ukrainian refugees with dependents use different strategies, depending on their personal circumstances[60]: they may flee together with parts of their previous networks (grandmothers, sisters etc.), or else to some place where a potential care support can be attained (from relatives, friends etc.), or they can reconstruct these networks from scratch — usually connecting with other female refugees from Ukraine.

Being deeply gendered and predominantly depoliticised, the newly emerging care networks of Ukrainian refugees play an important role in social reproduction. The inability to create such networks can, in some cases, even lead to refugees returning to Ukraine. Fear of losing such usual connections may equally play a role in one’s decision to flee from the war. Informal care networks or lack of them are also important for IDPs: lacking these networks or not being able to create them may be a major obstacle in women’ prospects of settlement, employment and even in obtaining humanitarian aid and support[61].

Beyond the depoliticizsd adaptation of social reproduction on the level of individual networks and small groups, a political process has been continuing on the level of movements. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, despite the very unfavourable circumstances, the abovementioned movement of nurses continues to operate. They have managed to register a trade union, organised several small-scale demonstrations (despite the wartime-related restrictions on protests), provided humanitarian support for healthcare workers, supported them in courts, and built connections with local, foreign and international organizations. Continuing to voice the problems and criticize the policies, the movement of nurses can potentially narrow the gaps of care and have a structural impact on social reproduction during and after the war.

Aggression, depletion and solidarity

While the reproduction of capitalist relations “is permanently vulnerable to the possibility of crises and catastrophe”[62], in the Ukrainian context it has been undergoing a number of crises which have been multiplying each other’s negative impact on society for some decades now. With neoliberal cuts and reforms, war in Eastern Ukraine, population displacement and the COVID-19 pandemic, the gaps in care infrastructure were widening and social reproduction was already jeopardized. This was especially true in spatially and structurally underprivileged settings — for rural populations, internally displaced persons, in communities near the frontline, and others.

Still, much changed on 24 February 2022. Currently Russian aggression is the main threat to social reproduction in Ukraine: it kills and injures, it destroys care infrastructure and networks, and enforces institutional adaptation which unavoidably further widens the gaps of care. Furthermore, governmental policies (or lack of them) create a reality where the costs of war and the war-related crises are predominantly shifted on the shoulders of households and communities[63]. Now, in Ukraine we can see the geographical and structural spaces where the radical depletion of social reproduction[64] occurs at the crossroads of military aggression, the related (sometimes catastrophic) environmental impact and economic crises, and declining social provision from the state.

At the same time, because of massive population displacement across the border, part of social reproduction is externalised, with European and other countries’ care infrastructure taking a huge share of the load. While this externalisation — something which can be provisionally called “infrastructural solidarity — has undeniable merits, in softening the shock of destruction on individual and general level, it also has its obvious potential to produce ambiguous changes in Ukrainian society’s social reproduction in future. This potential grows with time, with lack of socially-oriented governmental policies in Ukraine during the war and in the perspective of reconstruction, and is heavily conditioned by the outcome of the Russian aggression and its uncertainty: when, and how, the war will end.

Within Ukraine or beyond its borders, networks of solidarity play their role in reproduction of individuals, families, communities and society in general. While some — including informal networks of Ukrainian refugees — help to manage social reproduction on the day-by-day scale, others politicise it. The latter — in the form of trade unions, organisations and political initiatives on local, national and transnational levels — may best have a positive impact on the shape of care infrastructure and social reproduction in Ukraine.

Footnotes

- ^ Bakker, I., & Silvey, R. (2012). Introduction: Social reproduction and global transformations–from the everyday to the global. In Beyond States and Markets (pp. 1-15). Routledge;Katz, C. (2001). Vagabond capitalism and the necessity of social reproduction. Antipode, 33(4), 709-728;Mies, M. (2007). Patriarchy and accumulation on a world scale revisited.(Keynote lecture at the Green Economics Institute, Reading, 29 October 2005). International Journal of Green Economics, 1(3-4), 268-275.

- ^ Vogel L. Domestic Labor Revisited / L. Vogel // Science & Society. – 2000. – Vol. 64. – № 2. – P. 151-170.

- ^ Gimenez, M. E. (2005). Capitalism and the oppression of women: Marx revisited. Science & Society, 69(1: Special issue), 11-32;Mies, M. (2007). Patriarchy and accumulation on a world scale revisited.(Keynote lecture at the Green Economics Institute, Reading, 29 October 2005). International Journal of Green Economics, 1(3-4), 268-275;Federici, S., & Cox, N. (1975). Counter-planning from the kitchen: wages for housework, a perspective on capital and the left. Revolution at point zero: Housework, reproduction and feminist struggle, 28-40;Bakker, I., & Gill, S. (2003). Global political economy and social reproduction. In Power, production and social reproduction: Human in/security in the global political economy (pp. 3-16). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- ^ Gimenez, M. E. (2005). Capitalism and the oppression of women: Marx revisited. Science & Society, 69(1: Special issue), 11-32;Dutchak, O. (2018). Conditions and sources of labor reproduction in global supply chains: The case of Ukrainian garment sector. Bulletin of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv: Sociology, 9, 19-26.

- ^ P.718 in Marx, K. (1990). Capital: Vol. 1. Penguin Books.

- ^ Dutchak, O. (2018). Crisis, War and Austerity: Devaluation of Female Labor and Retreating of the State. Ukraine. Kyiv: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

- ^ Dutchak, O. (2018). Crisis, War and Austerity: Devaluation of Female Labor and Retreating of the State. Ukraine. Kyiv: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

- ^ Dutchak, O., Tkalich, A., & Strelnyk, O. (2020). Who cares? Kindergartens in the context of gender inequality. Center for Social and Labor Research.

- ^ Dutchak, O. (2018). Crisis, War and Austerity: Devaluation of Female Labor and Retreating of the State. Ukraine. Kyiv: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

- ^ There are very different types of those (like live-in and visiting care, boarding houses for elderly and people with disabilities, geriatric boarding houses etc.), some of them host both elderly people and other categories; facilities are financed within different Ministries, central and local authorities, and statistics on them is scattered through multiple sources.

- ^ Data from the report “Social protection of Ukrainian population”.

- ^ Data from the report “Social protection of Ukrainian population”.

- ^ These figures should be taken into account cautiously, as the number of people in need of social assistance, “detected” by the Ministry of Social Services, does not necessarily fully correspond to reality. This number fluctuates substantially during some years with no clear structural courses behind – see below.

- ^ Kravchuk, O. (2016). Changes in the Ukrainian economy after the Maidan. Spilne/Commons (https://commons.com.ua/en/zmini-v-ukrayinskij-ekonomitsi-pislya-majdanu/).

- ^ Kravchuk, O. (2015). The origins of Ukraine’s debt dependence. Spilne/Commons (https://commons.com.ua/en/formuvannya-zalezhnosti/).

- ^ Lomonosova, N. (2021). How they optimized care: philosophy and practice of the social services reform [In Ukrainian, Yak optymizuvaly turbotu: filosofia ta praktyka reform sotsialnykh posluh]. Spilne/Commons (https://commons.com.ua/uk/yak-optimizuvali-turbotu-filosofiya-ta-praktika-reformi-socialnih-poslug/).

- ^ Author’s calculation based on data from the State Statistics Service (Statistical bulletin ‘General educational institutions of Ukraine, 2016/2017 school year’ – https://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_u/publosvita_u.htm) and from the Ministry of Education and Science (Informational bulletin ‘Institutions of general secondary education of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, other Ministries and departments and private institutions, 2018/2019 and 2019/2020 school years’ https://iea.gov.ua/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Zakladi-zagalnoyi-serednoyi-osviti-Ministerstva-osviti-i-nauki-Ukrayini-inshih-ministerstv-i-vidomstv-ta-privatni-zakladi_2018-2019-2019_2020-n.r.pdf).

- ^ Dutchak, O., Tkalich, A., & Strelnyk, O. (2020). Who cares? Kindergartens in the context of gender inequality. Center for Social and Labor Research.

- ^ Dutchak, O. (2018). Crisis, War and Austerity: Devaluation of Female Labor and Retreating of the State. Ukraine. Kyiv: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

- ^ Author’s calculation, based on the data from the State Statistics Service (Statistical bulletin ‘Healthcare institutions and morbidity of the population in 2014’) and from the Ministry of Healthcare (‘Medical staff and network of healthcare institutions of Ukraine in 2020-2021’).

- ^ Evaluation of such a reorganization was mixed – usually it was praised by politicians, received mixed comments from NGOs, and criticized by healthcare workers.

- ^ Data from the report “Social protection of Ukrainian population”.

- ^ This sharp decrease was most likely related to social reform and decentralisation, where newly created communities had not managed yet to establish “providers” of services. While this means that some people lost access to social support, this dynamic may have changed in the following years – additional data is needed to evaluate it further.

- ^ Data from the report “Social protection of Ukrainian population”.

- ^ Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights. (2017). Monitoring of the places of restricted freedom: state of implementation of the national preventive mechanism, report for 2016 [In Ukrainian, Monitorynh mists nesvobody v Ukraini: stan realizatsii natsionalnoho preventyvnoho mekhanizmu: dopovid za 2016 rik].

- ^ Ukrainian National Academy of Science, Institute of Demographic and Social Reseach, he United Nations Population Fund. (2014). Population of Ukraine: Imperatives of demographic aging [In Ukrainian, Naselennia Ukrainy: imperatyvy demohrafichnoho starinnia].

- ^ Dutchak, O. (2020). Mission Impossible: Achieving Gender Equality within Neoliberal Austerity (example from Ukraine). Berlin, Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

- ^ Dutchak, O., Tkalich, A., & Strelnyk, O. (2020). Who cares? Kindergartens in the context of gender inequality. Center for Social and Labor Research.

- ^ In 2020 the legal minimum wage was UAH 3,873 after taxes, or approximately € 125/month.

- ^ Lomonosova, N. (2021). How they optimized care: philosophy and practice of the social services reform [In Ukrainian, Yak optymizuvaly turbotu: filosofia ta praktyka reform sotsialnykh posluh]. Spilne/Commons (https://commons.com.ua/uk/yak-optimizuvali-turbotu-filosofiya-ta-praktika-reformi-socialnih-poslug/).

- ^ Dutchak, O., Oksiutovych, A. (2023). Case-study: elderly care regime in Ukraine. Internal working-paper within the project ‘Researching the Transnational Organization of Senior Care, Labour and Mobility in Central and Eastern Europe’.

- ^ Dutchak, O. (2018). Crisis, War and Austerity: Devaluation of Female Labor and Retreating of the State. Ukraine. Kyiv: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

- ^ This was partially done through freezing of the legal subsistence minimum, on which calculations for most of the social payments are done.

- ^ Dutchak, O., Tkalich O. (2021). Single mothers in Ukraine. Poverty, rights violations and potential for protest. [In Ukrainian, Odynoki materi v Ukraini. Bidnist, porushennia prav ta potentsial do protestu]. Spilne/Commons (https://commons.com.ua/uk/odinoki-materi-v-ukrayini-bidnist-porushennya-prav-ta-potencial-do-protestu/).

- ^ Slovo i Dilo. (2021). Number of IDPs in Ukraine and which social assistance they have got in July [In Ukrainian, Skilky v Ukraini pereselentsiv i yaku dopomohu vony otrymaly v lypni]. (https://www.slovoidilo.ua/2021/08/26/infografika/suspilstvo/pereselenczi-ukrayini-skilky-yix-ta-yakyx-oblastyax-prozhyvayut).

- ^ As it often happens, most of the refugees or IDPs stay close to their home – in the bordering territories and regions.

- ^ Ryabchuk, A. (2023). War on the horizon: Infrastructural vulnerability in frontline communities of the Donbas. Focaal, 2023(96), 46-56.

- ^ Lomonosova, N. (2022). Social protection of the population during the pandemic: what are the problems of those who care about us [In Ukrainian, Sotsialnyi zakhyst naselennia na tli pandemii: z yakymy problemamy stykaiutsia ti, khto turbuietsia pro nas]. CEDOS (https://cedos.org.ua/soczialnyj-zahyst-naselennya-na-tli-pandemiyi-z-yakymy-problemamy-stykayutsya-ti-hto-turbuyetsya-pro-nas/).

- ^ Dutchak, O. (2021). ‘Manage somehow’: notes from Ukraine on care labor at a time of local and global crisis. TSS Platform (https://www.transnational-strike.info/2021/01/05/manage-somehow-notes-from-ukraine-on-care-labor-at-a-time-of-local-and-global-crisis/).

- ^ Tkalich, O. (2020). ‘Be like Nina’: how the movement of nurses evolved during the pandemic and healthcare reform [In Ukrainian, ‘Bud yak Nina’: yak pid chas pandemii ta medreformy zarodyvsia rukh medsester]. Spilne/Commons (https://commons.com.ua/uk/ruh-medsester-pid-chas-medreformy-i-pandemii/).

- ^ In 2022 the basic wage of a nurse was supposed to be UAH 13 500 (before taxes) or approximately 420 EUR.

- ^ According to official data from https://saveschools.in.ua/en/. Data accessed in September 2024, however the source itself does not indicate the exact period (hence, data may be outdated).

- ^ Institute of Education Analytics. Main Education Statistics, 2022-2023 (https://iea.gov.ua/naukovo-analitichna-diyalnist/analitika/osnovni-czyfry-osvity/). Data dated as March 2023.

- ^ https://life.pravda.com.ua/society/v-ukrajini-cherez-viynu-poshkodzheni-ponad-3-5-tisyachi-zakladiv-osviti-300221/.

- ^ According to calculation based on State Statistic Service data ‘Education’ (https://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/operativ/pro_stat/Prosto/Osvita/osvita.pdf) , the general number of education institutions in 2019-2020 was 31192.

- ^ Institute of Education Analytics. Main Education Statistics, 2022-2023 (https://iea.gov.ua/diyalnist/naukovo-analitichna-diyalnist/osnovni-czyfry-osvity/). Data dated as March 2023.

- ^ Shwarts, D. (2024). Every seventh school in Ukraine is damaged because of RF’s attacks – MON [In Ukrainian, Kozhna sioma shkola v Ukraini poshkodzhena cherez ataky RF – MON]. DW (https://www.dw.com/uk/kozna-soma-skola-v-ukraini-poskodzena-vnaslidok-atak-rf-minosviti/a-68073183).

- ^ Kharkiv Anticorruption Center. (2024). Rethinking education. What is wrong with school education in Kharkiv during the war and how this can be changed? [In Ukrainian, Pereosmyslyty osvity. Shcho ne tak zi shkilnym navchanniam u Kharkovi pid chas viyny ta yak tse zminyty?]. (https://anticor-kharkiv.org/our-work/pereosmyslyty-osvitu-shcho-ne-tak-zi-shkilnym-navchanniam-u-kharkovi-pid-chas-viyny-ta-iak-tse-zminyty/).

- ^ Ministry of Healthcare of Ukraine. (2023). After over twenty months of war the Russian Federation has already damaged 1,468 medical facilities and totally destroyed 193 [In Ukrainian, Za ponad 20 misiatsiv viyny rf vzhe poshkodyla 1468 obyektiv medzakladiv ta shche 193 zruynuvala vshchent]. (https://moz.gov.ua/article/news/za-ponad-20-misjaciv-vijni-rf-vzhe-poshkodila-1468-ob%e2%80%99ektiv-medzakladiv-ta-sche-193-zrujnuvala-vschent-).

- ^ Author’s calculation based on the Ministry of Healthcare report ‘Medical staff and network of healthcare institutions of Ukraine in 2019-2020’.

- ^ Governmental portal. (2023). The government has obliged to increase the salaries of medical workers in the front-line territories and in the zone of active hostilities [In Ukrainian, Uriad zobovyazav pidvyshchyty zarobitnu platu medykam na pryfrontovykh terytoriakh ta v zoni aktyvnykh boyovykh diy]. (https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/uriad-zoboviazav-pidvyshchyty-zarobitnu-platu-medykam-na-pryfrontovykh-terytoriiakh-ta-v-zoni-aktyvnykh-boiovykh-dii).

- ^ In 2023 the minimum wage was UAH 6700 before taxes – approximately €167/month.

- ^ Lomonosova, N., Babych, K. (2022). Social protection and war in Ukraine (24 February – 30 April) [In Ukrainian, Sotsialnyi zakhyst i viyna v Ukraini (24 liutoho – 30 kvitnia)]. CEDOS (https://cedos.org.ua/researches/soczialnyj-zahyst-i-vijna-v-ukrayini-24-lyutogo-30-kvitnya-2022/).

- ^ Amnesty International. (2023). ‘They live in the dark’. Older people’s isolation and inadequate access to housing amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- ^ Ukrainian National Academy of Science, Institute of Demographic and Social Reseach, he United Nations Population Fund. (2014). Population of Ukraine: Imperatives of demographic aging [In Ukrainian, Naselennia Ukrainy: imperatyvy demohrafichnoho starinnia].

- ^ For men of the same age group the proportion is not that much different – 27 and 41 percent respectively. But we should note that in 2021 there were 27 percent fewer men than women in this age group in Ukraine. Participation of both elderly men and women in childcare further decreases with age due to health issues.

- ^ UNHCR. (2023). Ukraine Refugee Situation. UNHCR Operational Data Portal (last updated 31 December 2023).

- ^ UNHCR. (2023). Regional protection profiling and monitoring: protection risks and needs of refugees from Ukraine, publish date: 15 December 2023.

- ^ Krivonos, D. (2022). Who stands with Ukraine in the long term? On the invisible labour of Ukrainian migrant communities. LeftEast (https://lefteast.org/who-stands-with-ukraine/).

- ^ Dutchak, O. (2023). Together we stand: enforced single motherhood and Ukrainian refugees' care networks. Spilne/Commons (https://commons.com.ua/en/u-yednosti-sila-vimushene-samotnye-materinstvo-ta-merezhi-doglyadovoyi-pidtrimki-ukrayinskih-bizhenok/).

- ^ Buts, O., Gu, O. (2023). Every day is a rainy day: what impoverished motherhood in Ukraine is like. Spilne/Commons (https://commons.com.ua/en/problemi-materiv/).

- ^ Caffentzis, G. (1999). On the notion of a crisis of social reproduction. Women, development, and labor of reproduction: Struggles and movements, 153.

- ^ Lyubchenko, O. (2022). On the frontier of whiteness? Expropriation, war, and social reproduction in Ukraine. LeftEast.

- ^ Chilmeran, Y., & Pratt, N. (2019). The geopolitics of social reproduction and depletion: the case of Iraq and Palestine. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 26(4), 586-607.