My lecture[1] discusses Ukrainian literary modernism from the perspective of various socialist visions of modernity and is aimed to combine different cases from entangled Ukrainian history of the interwar period through the figure of literary critic, politician and sociologist Mykyta Shapoval-Sriblians’kyi.

I propose to consider socialism, including the radical Bolshevik one, – as a distinct universalist framework for the development of the Ukrainian national project before and after the 1917 Revolution. I want to probe specifically the socialist projects of Ukrainian nation-building in their dialectical relationship with various undertakings of cultural and political modernization, which had already begun in the 19th century and continued in the early-Soviet period and in the Ukrainian emigration.

This approach allows us to recognize several distinct and competing models for the formation of a modern Ukrainian nation, where socialism, as an emancipatory ideology and practice, intertwined with various projects of national liberation. I will focus on two such models, analyzing them through two case studies of socialist projects of modernization.

The history of the literary magazine “Zaboi/Literary Donbas,” published in Bakhmut/Artemivs’k in 1923–1935 gives us a chance to investigate the early-Soviet project of national building. This model of modernity sought social and cultural modernization within the universalist framework of communist ideology; an ideology that promoted a transnational Soviet modernity, though it was in the end abandoned by the early 1930s.

The life and work of Mykyta Shapoval – a crucial figure for Ukrainian political and cultural history – allows us to articulate a different model of socialist Ukraine deeply rooted in Drahomanov’s ideas and which emerged in opposition to Marxism and later to the Bolshevik’s one. Shapoval’s project of a modern nation attended to the national specificities of Ukraine, including its large peasant population, calling for the intelligentsia to lead a gradual development of industry and the education of the peasantry in order to enact social transformation.

The interplay between universalism and particularism (or between socialism and nationalism) presents these two visions of modernity for the Ukrainian nation. In each case, literature played a special role as one of the most influential tools for cultural modernization and nation-building.

The starting point of my lecture – which I will develop as a non-chronological narrative – is the city of Bakhmut, situated in the Donetsk Region. Bakhmut was historically a renowned center of industrialization playing a key role in shaping the landscape of industrial growth in Ukraine during the tsarist and early Soviet periods. In the pre-revolutionary years the city was famous mostly for its salt mining. In the early-Soviet period, the machine industry began to develop.

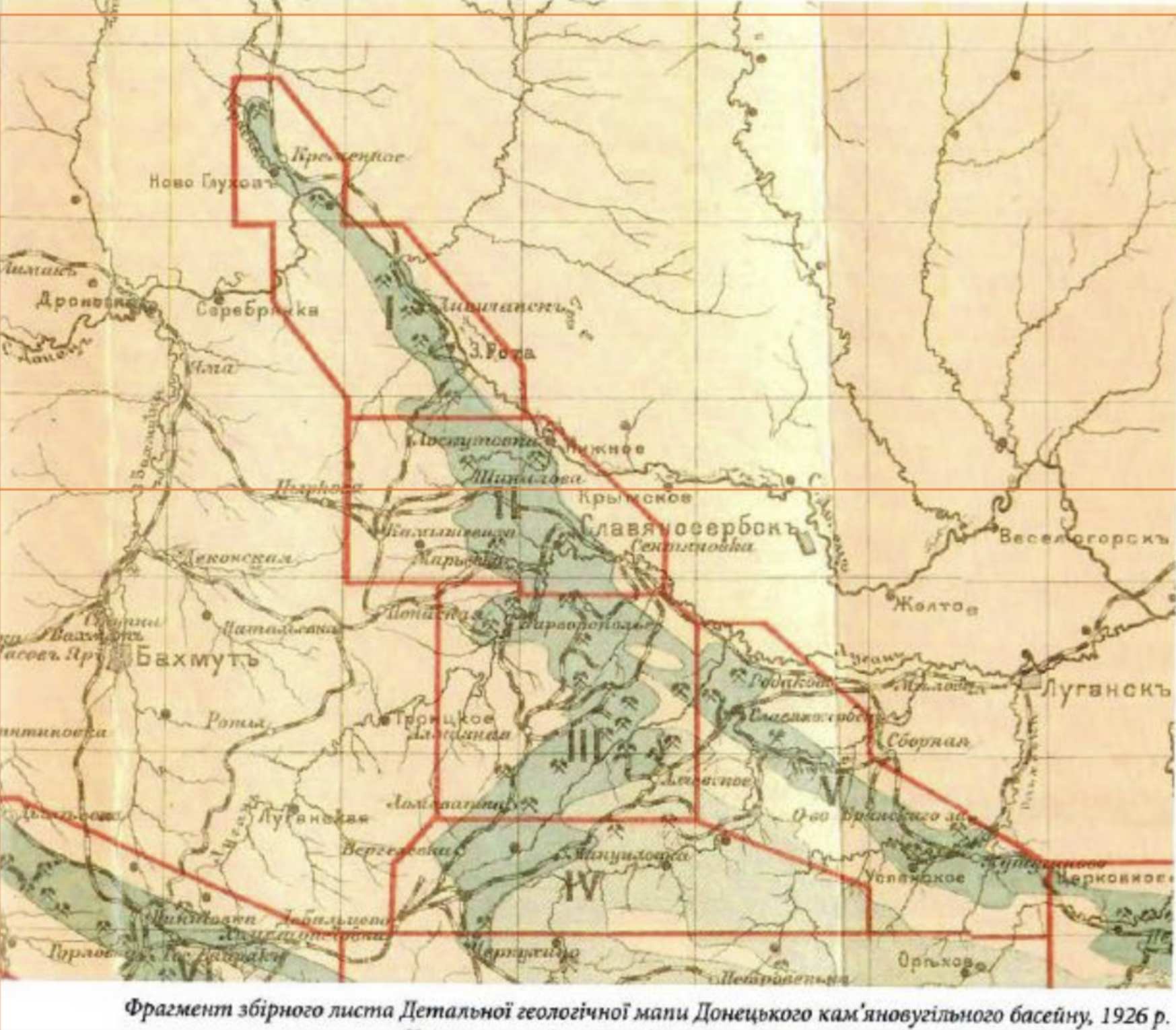

If you look on the map from 1926, you will see that Bakhmut is very close to such towns as Kreminna, Sribl’ianka, Lysychans’k, Popasna, Debal’tseve, and Horlivka, which formed the core of the Donetsk coal basin. Next map shows the boundaries of the so-called “Old Donbas” and the “Great Donbas,” developed during the 20th century.

Fragment of the Detailed geological map of the Donetsk Coal Basin, 1926

Bakhmut was one of the centers of industrialization and modernization of the Donbas region for several decades before the end of the 19th century. However, what often escapes attention is that Bakhmut made a significant yet less-explored contribution to the cultural modernization and nation-building processes, not only in Imperial and early Soviet Ukraine but also across state borders – in the interwar Ukrainian émigré community.

From the end of the 19th century onward, Donbas was perceived as a very special region with its coal-mining and heavy industry. The development of coal-mining and industrial infrastructure contributed to the settlement of many foreign specialists – from Great Britain, Belgium, and Germany but also from various parts of the Russian Empire. The urban diverse population and its large working class made it different from the neighboring Russian and Ukrainian regions.

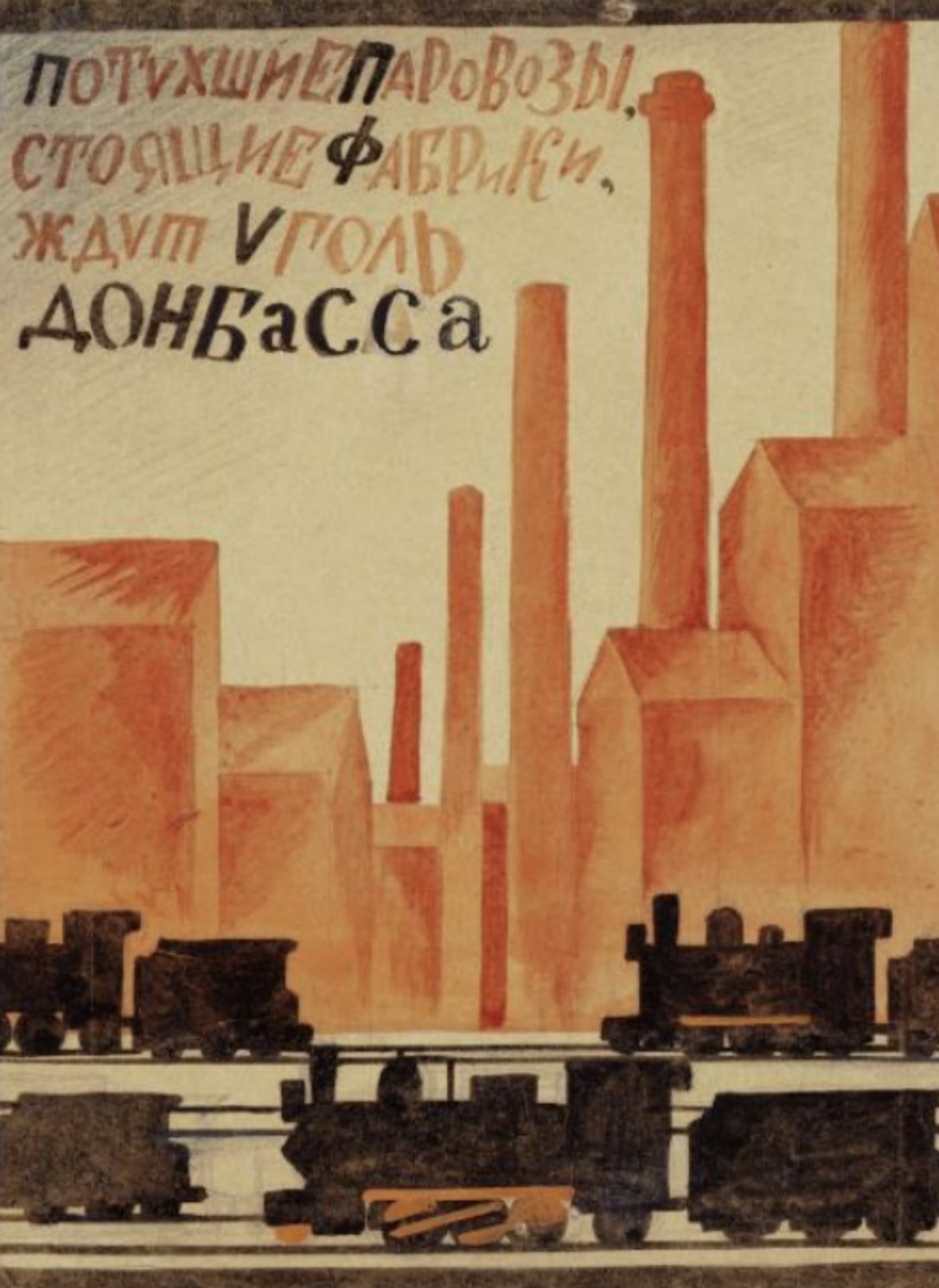

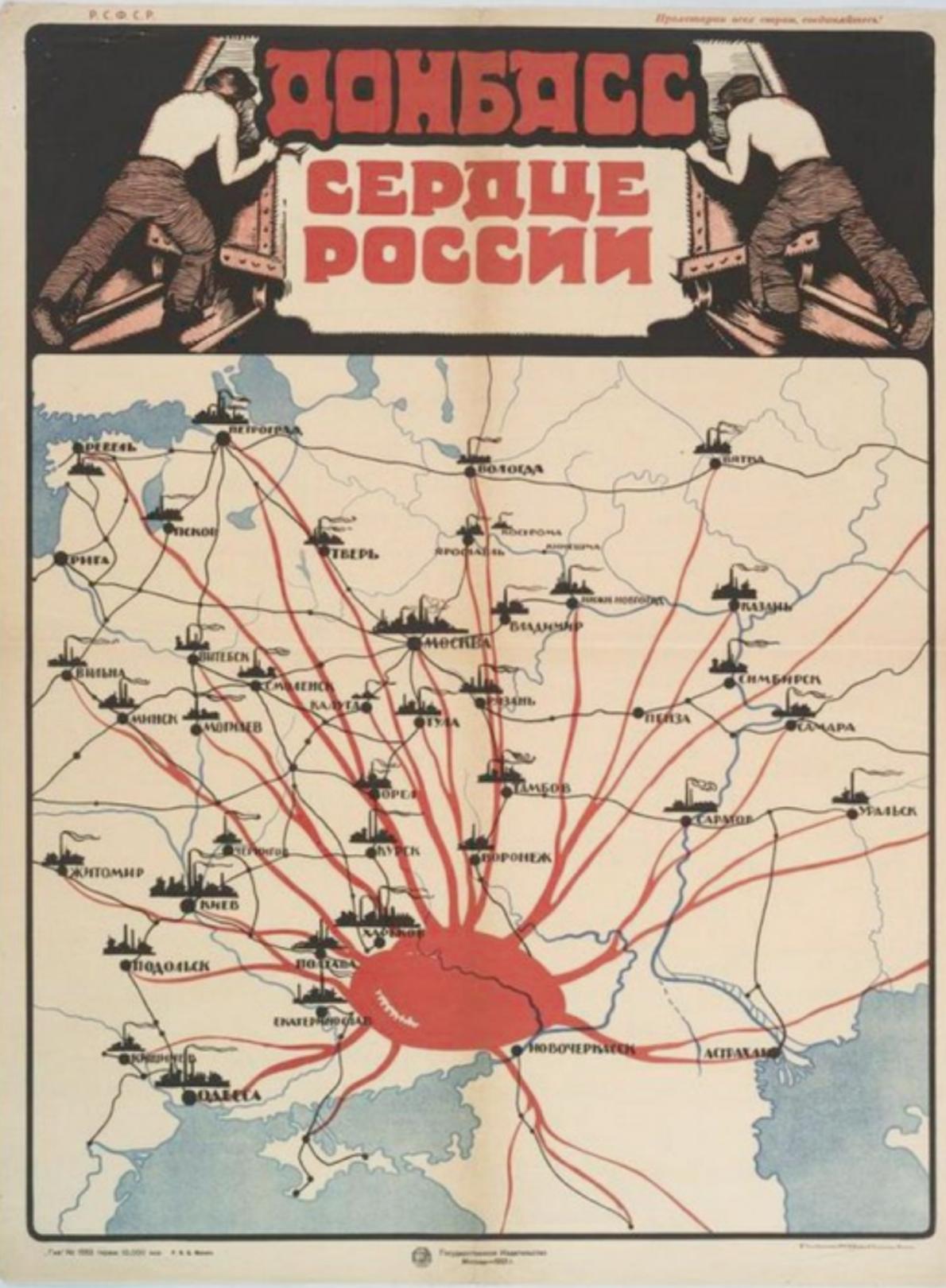

Donbas was crucial for the industry of the Russian Empire and of course, it was even more important for the new Soviet state. The propaganda poster designed by Kharkiv constructivist Vasyl’ Ermilov contained the call: “Extinct locomotives, idle factories await Donbas coal.” On the propaganda poster from 1921 the Donetsk region is depicted as a heart with blood vessels connecting it to other cities in the Soviet Union.

Vasyl’ Ermilov (1920) “Extinct locomotives, idle factories await Donbas coal.”

“Donbas [Donetsk Basin] – the heart of Russia” 1921, Unknown Artist

In 1922 Lenin wrote: “You know that Donbass is the centre, the real basis of our entire economy. It will be utterly impossible to restore large-scale industry in Russia, to really build socialism—for it can only be built on the basis of large-scale industry—unless we restore the Donets Basin…”[2]

Beginning from the late 1920s, Joseph Stalin began to implement the so-called “Lenin’s plan of peaceful socialist construction.”[3] This meant the development of heavy industry together with the collectivization of the agricultural sector and the “cultural revolution.”

Literature and the arts were considered as an effective tool of cultural revolution – and – therefore of promoting industrialization itself. In the 1920s Donbas became a dominant topic of this new type of literature, especially during the First five-year-plan (1928–1932).

The early Soviet approach to the project of cultural and political modernization could be illustrated by the literary and socio-political monthly magazine “Zaboi,” [The Mining Face] published in 1923–1935 in Bakhmut (the city from 1924 was renamed into Artemivs’k). The magazine was published by the Union of Donbas proletarian writers as a part of All-Russian association of proletarian writers. The magazine and the literary organization “Zaboi” were founded by the Soviet Russian writers Evgenii Shwartz, Mikhail Slonimsky and Boris Oleinikov. They came to Bakhmut to visit Shwartz’s father, who worked as a doctor at the salt mine at that time[4].

“Zaboi” claimed to be the only true literary representative of the Donbas proletariat, and it had numerous satellite branches in other regional towns. The magazine published stories, novels, poems, and reports that depicted the daily life of industrial Donbas, production problems at plants, factories, and mines, etc. It became a kind of Soviet “chronicle” of its time and laid the foundation for further developments in the poetics of Socialist realism.

Between 1923–1928, the journal published materials mostly in Russian, except for occasional poems by Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Franko. But starting in September 1929 it began publishing mostly in Ukrainian and was edited by the Ukrainian writers Ivan Le and Ivan Mykytenko. They came from Kyiv to promote the Ukrainization policy of the magazine and literary organization itself.

Among the Soviet Russian poets who contributed to the magazine were Nikolai Oleinikov, Demian Bednyi, Eduard Bagritsky, Sergei Esenin, and Mikhail Zoshchenko. Among local Donbas poets and writers let me name Volodymyr Sosiura, Boris Gorbatov and Pavel Besposhchadnyi, who later became renowned classics of Socialist realism. But alongside professional writers, the journal’s main contributors were workers from coal mines and iron mills. In addition to social issues, they addressed the new socialist aesthetics of coal-mining and industrial production.

To illustrate the aesthetics of production literature, let me draw your attention to a poem by V. Kramators’kyi (real name – Vasyl’ Ivaniv) in Ainsley Morse translation (published in the 8th issue for 1930)[5].

***

Гудуть машини й еленґи в огні,

Втілена в сталь задимлюється мрія,

То йде у гомоні на простори сумні

Важка, як сталь, велика індустрія.

І я стою, розхристаний вогнем,

Сплітаю сталь закурений i димний

А день співа розлунених поем,

Яких ще світ не складав у гімни.

Крани снують, заплутані в дроти,

Чавунний плав обвітрює обличчя,

Як механізм годинника пустив.

Снують трансмісії в заведеній величчі.

Огнева лють роз‘ятрила чавун,

Промчала день у посвисті сирени

I знов підвівсь гарячий в небо лунь,

Ковтнули знов i домни i мартени.

Oгневі дні сталеві i чудні

Повстали в яв, у втіленую мpiю.

I йде на степ задимлена, в огні

Важка, як сталь, велика індустрія.

В. Краматорський[6]

***

Loud drone of machines, ship-berths in flames,

Embodied in steel, the dream sits smoking,

So amidst clamor, toward mournful spaces

Heavy as steel moves the great industry.

And I stand, blown open by fire,

Weaving steel through smoke and soot,

And the day sings its echoing poems

That the world has yet to make into hymns.

Cranes are dashing, tangling with wires,

Iron smelt blasts wind against your face,

Like switching on a clockwork mechanism.

Transmissions dash in wound-up splendor.

Fiery fury enrages the cast iron,

Presses the day to siren’s whistle

And once again the hot moon rises in the sky,

Again gulp the blast-furnaces, Marten ovens.

These flaming days, steely and strange,

Rose up to be real, a dream embodied

And toward the steppe, smoking and aflame

Heavy as steel moves the great industry.

Translated by Ainsley Morse

This is an example of modernist coal-mining poetry, in which specific professional terms play a fundamental role in crafting the expressiveness and imagery of the text. Its language also employs neologisms, such as I знов підвівсь гарячий в небо лунь, where lun’ is a deformation of Russian [luna], meaning moon or the word розлунений [echoing], what indicates some of the avant-gardist strategies. The poem portrays a typical day at the iron mill, with its primary focus on celebrating the artistry of machine work. But in contrast to the later poetics of Socialist realism, it does not contain any ideological symbols related to socialist reality and the future. The language of the poem remains difficult and rich in metaphorical expression. All in all, we can claim that this poem stands as a noteworthy example of Constructivist poetry (primarily in terms of its content).

The history of “Zaboi” is intertwined with the implementation of the Korenizatsia policy. It was aimed, as Terry Martin observes, at preventing separatist nationalism from interfering with core Bolshevik objectives such as industrialization, collectivization, and the creation of a socialist society[7]. In the context of Donbas, this policy had a specific political objective. The Bolsheviks viewed the proletariat as their primary force in the region, but in reality, it was a smaller class when compared to the peasantry. As industrialization and subsequent urbanization took place, the cities became populated with former peasants who predominantly spoke Ukrainian. Andrii Movchan highlights that “Ukrainization aimed to facilitate the natural transition of these peasants into the proletariat while also fostering trust and political loyalty towards the Communist party.”[8]

In the June 1930 issue of “Zaboi,” an editorial article delves into this issue:

In Ukraine, as a legacy of the Tsarist regime, there is a rather unpleasant phenomenon – the bilingualism of the proletariat and the peasantry. The Ukrainian proletariat, over the course of ten years, became Russified, while the peasantry, economically and nationally oppressed, firmly retained all of its national characteristics, including its language. This aspect too often hinders understanding between the proletarian and the poor peasant. […] Aware of its task, the proletariat embarked on a campaign to understand the Ukrainian proletarian culture of today[9].

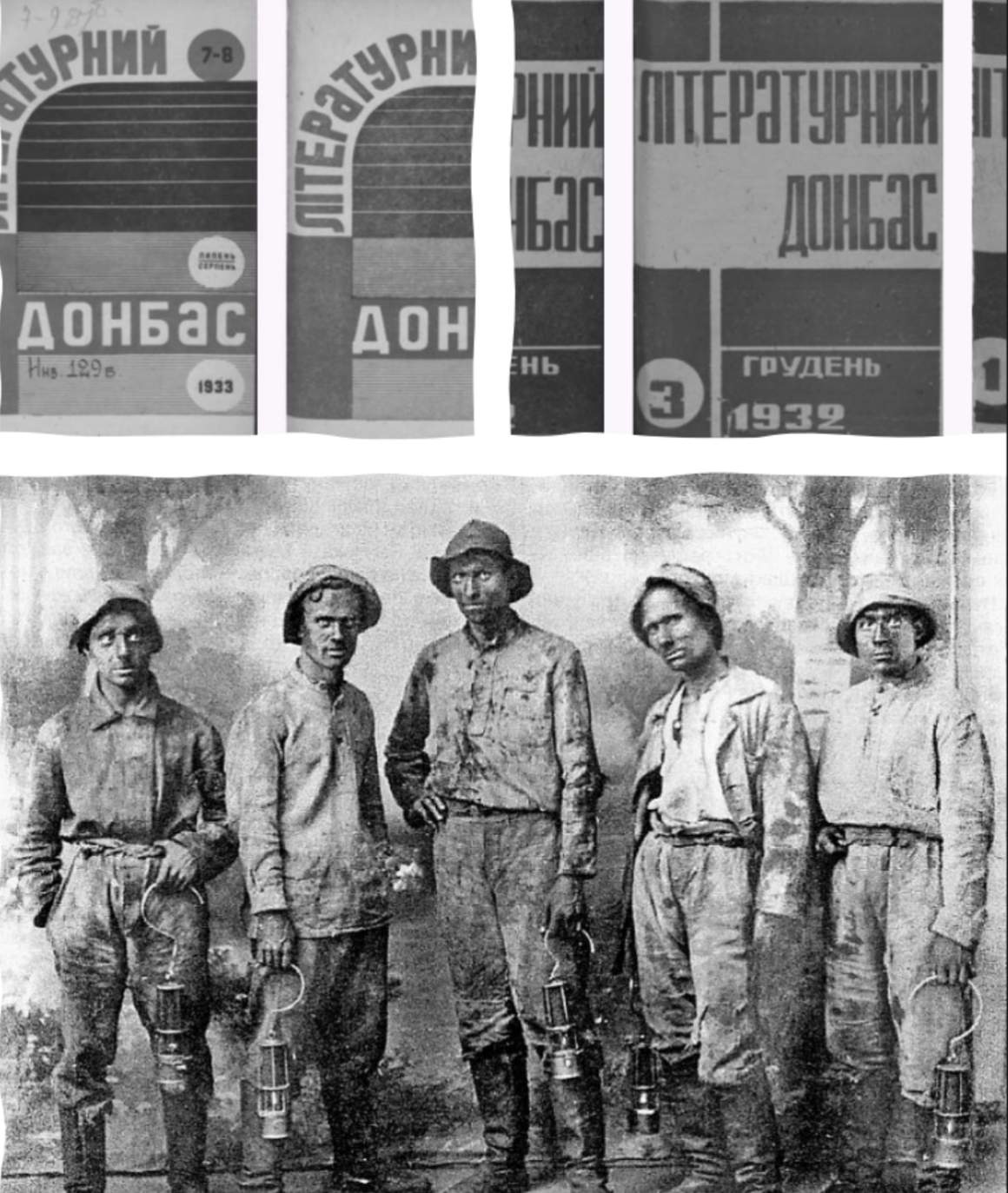

From October 1932 to September 1933 “Zaboi” was published under the title “Literary Donbas” (“Literaturnyi Donbas”), and all the materials of 8 issues in total were in Ukrainian. But at the same time, starting from the beginning of the 1930s it became clear that Stalin’s regime was preparing to suppress the Korenizatsiia policy. In 1933, “Zaboi’s” main editors, Hryhorii Barliuk and Vasyl’ Haivaronskyi were repressed. However, the magazine continued to exist in Russian until 1935.

“Literary Donbas”, 1932–1933

Therefore, “Zaboi” serves as an example of early Soviet efforts to promote nation-building in pursuit of the political objectives of forced socialist construction. The local historical narrative of Bakhmut and the role played by “Zaboi” demonstrate how these dynamics between national and socialist projects manifested in practice in the 1920s. From the 1930s, however, centralization of power led to the gradual phasing out or transformation of all political and cultural initiatives of the preceding decade.

My second case study illustrates that, historically, the emancipatory visions of socialism and nationalism were closely intertwined throughout the second half of the 19th century. In fact, Ukrainian cultural figures and political actors navigated these orientations long before the 1917 Revolution. One key figure among such thinkers was Mykyta Shapoval.

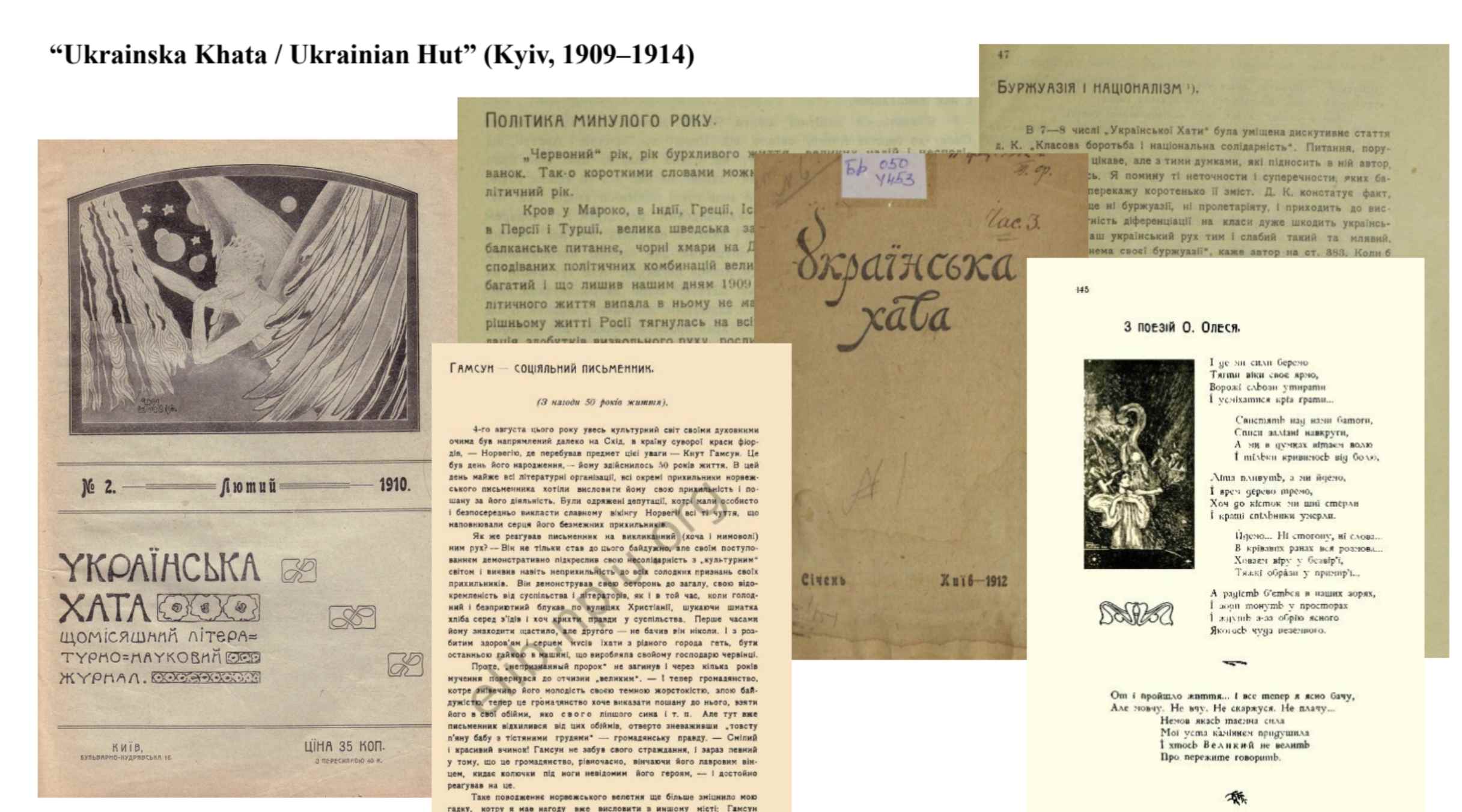

Within the historiography of Ukrainian literary modernism, Shapoval is widely recognized as Mykyta Sriblians’kyi – a poet and literary critic, one of the founders and editors of the journal “Ukrainska Khata.” This monthly publication, in circulation from March 1909 to August 1914 in Kyiv, was an important journal which encompassed literature, literary criticism, and addressed a social agenda. It is regarded as a central catalyst for the evolution of modernist influences within Ukrainian culture.

“Ukrainska Khata / Ukrainian Hut”, Kyiv, 1909–1914

Yet, for all his renown in the sphere of arts and letters, he is almost unknown as the political activist Mykyta Shapoval – a leader of the centrist faction of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries, a minister in the Ukrainian Central Council under Volodymyr Vynnychenko, and a founder of numerous emigré organizations in interwar Prague and Podebrady.

Mykyta Shapoval was born in 1882 in Sriblianka, which was part of the Ekaterinoslav gubernia at that time. The village was situated approximately 40 km from Bakhmut. He came from a poor family of ten children, and his father, Iuhym Shapoval, was a retired non-commissioned officer who had to make a living as a farm laborer (naimyt). This entailed frequent relocations for the family[10].

Mykyta Shapoval was a child of the era’s capitalist industrialization. Industrialization of the end of the 19th century brought a new type of primary education to the region which was unknown in the previous agrarian period of these lands. Children of the workers at the new mills and factories could receive secondary and technical education, primarily focused on mining engineering.

From the age of ten, Shapoval started working in the mines during his summer school breaks. Later he recollected this period in his Autobiography: In August [1892], I was already working in the mines: I worked ‘above’ near the coke ovens, children sorted coke, throwing away the completely decayed ones and keeping the heavy ones… From this work, my fingers bled a lot. I learned the whole process of coking, and by the color of the fire in the ovens, I could tell whether the coke was ready or not. I earned 20 kopecks a day there[11].

The installation of electric lighting in the mine left a profound impression on me. […] The electrician, Kluge (a German), who was responsible for the electrical wiring, appeared to be a demigod of science to me, and I aspired to become an electrician. However, I thought it was hopeless because the poor could not become electricians[12].

I quoted these two passages both to emphasize that Shapoval is conscious that he is a part of an exploited working class – and at the same time to show his admiration of industrial and technical progress. I also wanted to illustrate how the social and economic environment in which Shapoval grew up influenced the formation of his political views. In 1901 he joined RUP – the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party, the first underground political party in Central-Eastern Ukraine, founded in Kharkiv. In 1908, after almost a year of imprisonment in the Warsaw Citadel for his revolutionary activity, Shapoval moved to Kyiv.

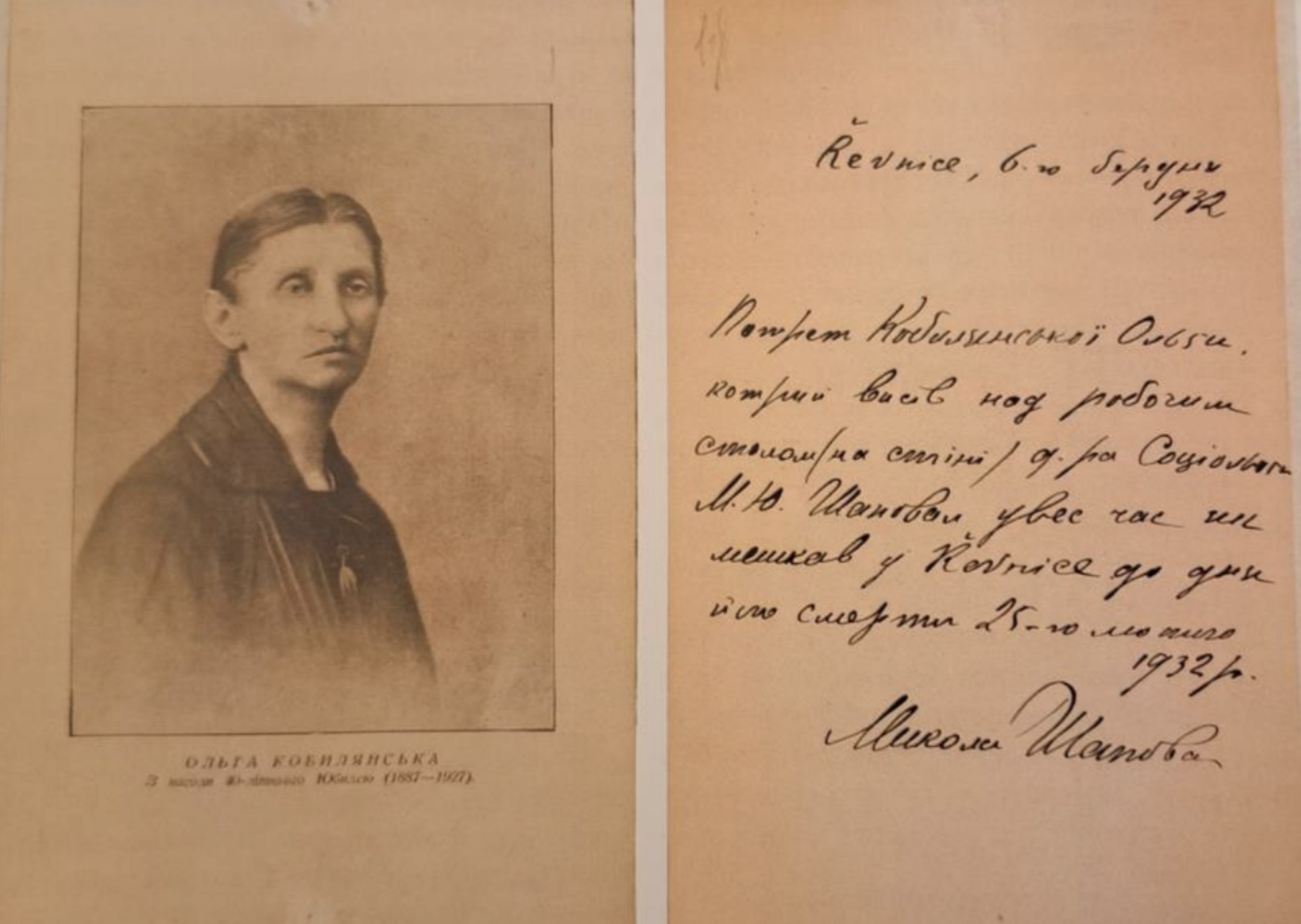

In Kyiv, together with his brother-in-arms, the literary critic Pavlo Bohats’kyi, Shapoval founded the literary-critical and socio-political monthly journal “Ukrainska Khata,” which laid the aesthetic and, one might add, ideological foundations for the further development of the Ukrainian movement for national liberation. The journal united, for example, such poets as Pavlo Tychyna, Maksym Ryl’s’kyi and Mykhail’ Semenko. Among prose writers, the most recognizable was a modernist feminist writer Olha Kobyl’anska who Shapoval named as one of the inspirations for “khat’anstvo” because she aesthetically prioritizes the individual over notions of class and social group.

A portrait of Olga Kobylyanska with a caption by Mykyta Shapoval

The general thesis about the role of “Ukrainska Khata” in Ukrainian literature is that the journal stood for “true beauty,” “Nietzscheanism,” and the national idea[13]. The main object of Khata’s criticism was “old-fashioned” populism; its credo was that Ukrainian national culture can and should be created by the intelligentsia. What often goes unnoticed, however, is that the journal's main theoreticians discussed the national project from both an aesthetic and emancipatory perspective, with an emphasis on social transformation, paving the way for future Revolution[14]. In other words, the goal of forging an independent Ukrainian nation was not considered separately from cultural modernization and social transformation.

In his 1926 memoir about the history of “Ukrains’ka Khata,” Shapoval states:

The term “Modernism” in Ukrainian criticism refers to the literary and social movement that emerged within “Ukrainska Khata.” To a certain extent, this is true, but it is only in a sense of newness, as “Khata” had nothing in common with literary decadence or religious modernism. Our Modernism entailed a re-evaluation of the Ukrainian movement and our relationship to Ukrainian history, a re-evaluation of our views on the contemporaries who contributed to the 1905 revolution, a re-evaluation of our liberation ideologies, and the search for a new ideology of liberation[15].

From this quote, it is evident that modernism, as Shapoval understood it, was a reimagining of familiar practices, both aesthetic and ideological, and it served as a tool in shaping the project of Ukraine's national and social liberation. Shapoval approached the national project through the universalist lens of social progress.

It is worth noting that Shapoval's primary political influence was Mykhailo Drahomanov, a Ukrainian socialist of the previous generation. On the other hand, Shapoval considered Drahomanov – a writer and political thinker – to be a crucial figure of the Ukrainian movement. Drahomanov regarded progressive cultural development and public education as key tools of political change and national liberation. It was Drahomanov to whom Shapoval appealed in many of his political essays written in exile. He also dedicated a separate 20-pages study to Drahomanov: “M. Drahomanov, an ideologist of New Ukraine” (Prague 1934).

During the Civil War from 1917 to 1921, Shapoval was politically active in various roles. However, after the fall of the Ukrainian People’s Republic in 1920, he appeared in exile in the First Czechoslovak Republic. For him, his exilic condition presented a singular opportunity to articulate a model of the modern Ukrainian nation that stood opposed to that of the Bolsheviks project.

The liberal government of interwar Czechoslovakia, led by President Tomáš Masaryk, created a supportive environment for cultural initiatives among émigrés from the former Russian Empire. In this context, Shapoval played a pivotal role within the Ukrainian émigré community. In 1921, he established the Ukrainian Civic Committee in Czechoslovakia (1921–5), which became the central organization which took over the development of scientific, educational, and humanitarian infrastructure in the Ukrainian emigration in Prague. Various Ukrainian educational institutions were established in Prague and Podebrady under the auspices of the Ukrainian Civic Committee. These included publishing houses and educational institutions, the Ukrainian Drahomanov Higher Pedagogical Institute in Prague, for example or the Ukrainian Economic Academy in Podebrady. In 1924, Shapoval was the driving force behind the creation of the Ukrainian Institute of Sociology, which published the magazine Suspil’stvo. He also took on the role of publisher and editor for the monthly publication Nova Ukraïna in Prague from 1922 to 1928.

Shapoval likewise led the anti-Soviet, revolutionary-socialist UPSR Foreign Committee (renamed the Foreign Organization in 1925) and strongly opposed the “bourgeois” (according to him) Ukrainian government-in-exile based in Paris.

All this is to say that Mykyta Shapoval's vision for modern Ukraine was distinct from both that of Simon Petliura and from that of Bolsheviks. His writings in exile demonstrate that he placed the defeat of the Ukrainian People’s Republic at the feet of the Ukrainian intelligentsia which had failed to align itself with the aspirations of the Ukrainian people. But he also emphasizes the constructive role that Ukrainian intellectuals—specifically those in emigration—might play in shaping a future independent Ukrainian socialist republic[16].

In his writings, Shapoval considered Ukraine as an independent actor within the revolutionary events and the broader historical narrative. In the interwar period his works helped to legitimize the Ukrainian People’s Republic and the 1917 Ukrainian Revolution in the international context of that time. His approach challenged the Bolshevik regime by emphasizing the necessity of socialist but not communist social change, which would enable the potential delegitimization of hierarchical political systems.

Shapoval’s 1926 work Challenges of the Ukrainian Emigration might be considered programmatic, in that it articulates a series of theses on the basis of his longstanding theoretical and practical views. Here his sociological theory (mainly sociography and cultural sociology of Ukraine) is linked to revolutionary practice.

The Ukrainian emigration, Shapoval argued, must work foremost “to establish Ukrainian statehood on united lands through the sovereign will of the Ukrainian people.”[17] To this end, the mission of the émigré intelligentsia was to prepare European consciousness for the inclusion of Ukraine in international law at a time when the united Ukrainian Socialist Republic could be established.

Shapoval saw the defeat of the Ukrainian Revolution in the inability of the Ukrainian intelligentsia to align itself with the aspirations of the Ukrainian people. He warned, however, that “it was folly to expect recognition and support from the European bourgeoisie. It was also folly to continue expecting this, because every Ukrainian revolution has been and can only be a social one. Why? Because the Ukrainian nation consists of 99% peasants, workers, and proletarian (social and economic) intelligentsia.”[18]

Shapoval believed that Ukrainian political propaganda in Europe ought to address itself to the working classes, within the left-wing, labor circles of Europe. He supposed that “from a Ukrainian perspective, the only viable policy can be a socialist policy in the realm of European labor.”[19]

His subsequent explications of his argument revolve around the three fundamental forms of organizing a nation to attain its objectives, encompassing the realms of politics, culture, and economics. Shapoval considered cultural work to be a crucial task for Ukrainian emigration and the very condition of being in emigration he regard as “a unique opportunity” (p. 13) to shape the future modern Ukraine.

In his argumentation Shapoval follows the iconic liberal Thomas Masaryk, asserting that “When someday two or three thousand truly cultured and scholarly individuals return from emigration, it will be like dynamite at home.”[20] Shapoval concludes by asserting that socialists must be organized to carry out this great challenge of emigration.

***

Having traveled from Bakhmut to Kyiv and then to Prague, I propose that we return to where we began; to Bakhmut. Bakhmut, and Donbas played a key role in shaping the formation of a modern Ukrainian nation, both rooted in aspirations toward societal and cultural modernization.

Shapoval claimed that only modernism as a new and progressive cultural phenomenon could lay a foundation for a modern Ukrainian nation; cultural work in accordance with modernist principles among Ukrainian émigrés could become a vital force in the further struggle for Ukraine’s social and national liberation. This is how he understood the dialectics between modernism, socialism and nationalism. Shapoval’s ideas were, otherwise, formulated against the background of the regional experience of the Donbas, articulated during the time of the Civil War and later – from a position of exile. In his exilic condition, he imagined that social reforms (and the Revolution itself) were to become the basis for the formation of an independent nation.

The Bakhmut literary magazine “Zaboi/Literaturnyi Donbas” illustrates another dynamic between modernism, socialism, and nationalism, where nationalism was galvanized (at least for a time) for the purpose of radical Soviet modernization and ended up generating novel, modern cultural forms. The Soviet regime used the Ukrainization policy to strengthen its power after the end of the Civil War, and as a result produced a new kind of Ukrainian culture, which navigated between the local and the universal. It shared something with the cultural formations of Soviet “national republics” and with some national movements in Europe and around the world. In this approach, nation-building was initially promoted as a tool for creating a transnational Soviet modernity. But as we know, this strategy—promoted from the “center”— was curtailed shortly thereafter and degraded to a mere Stalinist ornament of Soviet multi-nationality.

Footnotes

- ^ This lecture was presented at Harvard University in November 2023. FYI https://slavic.fas.harvard.edu/event/bakhmut-kyiv-prague-industrialization-literary-modernism-and-ukrainian-nation-building

- ^ V. I. Lenin, Eleventh Congress Of The R.C.P.(B.), March 27-April 2, 1922.

- ^ In spring 1918, Lenin authored the programmatic work The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Power, outlining the essential steps for constructing a socialist society. From a Marxist perspective on the transition from capitalism to socialism, Lenin underscored the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the abolition of private property, and the conversion of fundamental means of production into collective ownership. See also: Gladkov, I. (1958). Lenin’s Plan of Peaceful Socialist Construction. Problems in Economics, 1(6), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.2753/PET1061-199101066

- ^ Олег Шама, «Забой. Життя та смерть донбаського журналу українською, який знищили більшовики». The New Voice of Ukraine. 21 січня 2019: https://nv.ua/ukr/ukraine/events/rimi-ta-pristrasti-donbasu-istorija-donbaskoho-ukrajinomovnoho-literaturnoho-zhurnalu-rozhromlenoho-bilshovikami-2516183.html

- ^ Забой, № 8 (1930): 22.

- ^ Loud drone of machines, ship-berths in flames,Embodied in steel, the dream sits smoking,So amidst clamor, toward mournful spacesHeavy as steel moves the great industry.And I stand, blown open by fire,Weaving steel through smoke and soot,And the day sings its echoing poemsThat the world has yet to make into hymns.Cranes are dashing, tangling with wires,Iron smelt blasts wind against your face,Like switching on a clockwork mechanism.Transmissions dash in wound-up splendor.Fiery fury enrages the cast iron,Presses the day to siren’s whistleAnd once again the hot moon rises in the sky,Again gulp the blast-furnaces, Marten ovens.These flaming days, steely and strange,Rose up to be real, a dream embodiedAnd toward the steppe, smoking and aflameHeavy as steel moves the great industry.Translated by Ainsley Morse

- ^ Terry Martin. The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001. P. 31–76.

- ^ Андрій Мовчан, «Бахмутський журнал «Забой» — літопис соціалістичної українізації Донбасу». Спільне.Commons, 1 травня 2023

- ^ Національне культурне будівництво – на вищий щабель //Забой, 1930, № 10. С. 1–3.

- ^ Микита Шаповал. Схема життєпису. Біографія. Листи. Упоряд. та передм. А. М. Савченко. Харків, 2023.

- ^ Ibid., p. 26.

- ^ Ibid., p. 43.

- ^ See: Павличко Соломія. Теорія літератури. К.: Основи, 2009. С. 133–163; Oleh S. Ilnytzkyj, ‘Ukraïnska khata and the Paradoxes of Ukrainian Modernism,’ Journal of Ukrainian Studies 19, no. 2 (1994): 5–31.

- ^ The political and social dimension of early modernist tendencies in Ukrainian literature enabled G. Grabowicz to offer an elitist and Eurocentric critique of Ukrainian modernism, characterizing it, as represented by the “Young Muse” group and The Ukrainian Hut, as “considerably weaker than, say, Polish Modernism,” further diminished by the restricted initial discourse on modernism. See George G., Grabowicz, “Commentary: Exorcising Ukrainian Modernism,” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 15, no. 3/4 (1991): 281.

- ^ Микита Шаповал, «Доба хатянства», Українська хата, Київ, 1909–1914, Нью-Йорк: Українська громада ім. М. Шаповала, 1955. С. 35.

- ^ See his «Завдання української еміграції» (Прага, 1926).

- ^ Микита Шаповал. Завдання української еміграції. Прага, 1926. С. 4.

- ^ Ibid, 8.

- ^ Ibid, 9.

- ^ Ibid, 13.