Leila Al-Shami is a British-Syrian author and activist. She worked in the field of human rights protection in Syria, participates in international solidarity movements and co-authored the book "Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War" with Robin Yassin-Kassab. She also became known for her criticism of the "idiot anti-imperialism" of the Western left.

For the vast majority of Ukrainians, Syria before 2011 was probably just another Arab country, but after the war began, it came to symbolize the course that we would not want to see repeated in Ukraine. What distinguished the Assad regime from similar regimes in North Africa?

Throughout its history, the Assad regime’s response to any kind of dissent has always been violent repression. In the 1970s, there was a movement against the regime of Hafez Al Assad (the current president’s father). What originally started as a diverse movement, ended up being concentrated in the city of Hama and led by the Muslim Brotherhood. The regime’s response was to send in the air force and completely destroy the city. Between 20,000 & 40,000 civilians were killed and thousands more disappeared into regime prisons.

When the revolution erupted against the regime in 2011, many Syrians were optimistic and thought that Bashar Al Assad would bring in reforms. He had been in power for a decade, and many believed he was fundamentally different from his father; that he was a more outward-looking modernizer. When he came to power he spoke a lot about the need for reform, although mainly focusing on economic rather than political reforms. In the end, he responded to the people’s demands in the only way this regime knows – through terrorizing them into submission.

Having worked in human rights in Syria – with political prisoners, during Bashar’s first decade in power, I expected that the response to the revolution that started in 2011 would be repression. Although I didn’t expect the extent of the horror which unfolded, neither was I optimistic that Assad would quickly step down, as we saw dictators do in Tunisia and Egypt.

In Egypt, the military regime was in power, and its face was Mubarak. So it was easy for them to sacrifice Mubarak and keep the military in power. In Tunisia it was similar and they could sacrifice Ben Ali – there was a transition to democracy, but the old ruling class was waiting to come back. In Syria it is a bit different. In Syria, the head of the regime is the regime. Power is very much concentrated in the hands of the Assad family. In addition, the regime played the sectarian card – it’s from the minority Alawite sect – so managed to keep the support of many minorities against the predominantly Sunni opposition who it was prepared to enact genocidal violence against. Plus, the regime had the support of Russia and Iran who intervened to protect it.

Russian and Syrian Presidents Vladimir Putin and Bashar al-Assad during talks in the Kremlin on September 13, 2021. Image: Michael Klimentyev / AFP

Did Russian support play a significant role in helping Assad at the most difficult time for him?

Both Russia and Iran intervened to support the regime at moments when it was close to collapse and it looked like the revolution may succeed. Iran has given Syria massive financial and economic support and sent many militias to fight in Syria – which gave the conflict a sectarian dimension, as Iranian backed Shia militia were fighting the Syrian Sunni majority. And Iran directly intervened in 2013, allowing the regime to make significant advances against the opposition.

Russia provided planes and bombs and provides political support for the regime in international forums. And Russia directly intervened militarily in 2015 and has bombed many parts of the country.

If Russia and Iran had not intervened, Assad would have been forced out a long time ago. It is foreign support and foreign bombs which keep the regime in power, against the wishes of the vast majority of the Syrian population.

When I was reading your book Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, I just couldn't believe that such a tragedy could happen on such a scale. Seeing the horrors unfolding in Ukraine, the atrocities faced by Syrians become more tangible for us thus I really empathize for the people of Syria.

Yes, it’s devastating. It’s even more difficult because this horror started from a position of great hope and belief in the revolution. The revolution had so many successes. We saw, throughout the country, people self-organising to manage their daily affairs, setting up independent Local Councils and electing their members- their first experience of democracy in decades. People ran schools, water and sanitation facilities, hospitals. They set up independent newspapers and radio stations. Many women’s centers were established to encourage women to play an active role in the revolution and community life. None of this was possible under Assad’s totalitarianism where all civil society was curtailed. This was always the greatest threat to the regime – because it showed that a democratic alternative was possible – and this is why it was so savagely repressed.

Could you tell a little bit about the international policy of Syria's regime before 2011? What were the relationships with the USSR during the Cold War? How did this affect the regime?

Syria had a close relationship with the USSR during the Cold War, even though the Syrian regime brutally repressed communists. The USSR sponsored Hafez Al Assad, as it built relations to expand its sphere of influence in opposition to the Western powers. It provided weapons, training and intelligence to the Syrian army. Many Syrians travelled to the USSR to study during this period.

The USSR used this kind of cultural exchange as a tactic to indoctrinate citizens of allied countries with its ideology. Recently, I spoke with activists from West Africa, and they shared similar stories of the USSR supporting Africans to study there. Some from this generation of Africans now support Putin’s interventions in Africa, seeing it as a bulwark against western/French imperialism, so this tactic worked.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Hafez Al Assad was very quick to pivot towards the Gulf States and began implementing neo-liberal reforms to open up the country to Gulf investors. But relationships with Russia were maintained and when Putin came to power, he wanted to revive relationships with the Middle East, seeing it as helpful in Russia’s geo-political struggle against the west.

I don’t think Russia sees any ideological affinity with the Syrian regime and it doesn't perceive it to be an important partner. I think Russia's support for Assad has been used as a way to counter western influence and in the case of Syria, Russia is now more influential than the western powers.

Mother and child return to the shelter they found in the damaged school. They were unable to get a tent in a nearby IDP camp, Binish, April 2020. Image: Mohannad Zayat

I was also wondering about Russia using educational opportunities for the Global South to propagate its ideas. One of my doctors here in Vienna is Syrian, and he accepts Ukrainian patients in particular because he speaks Russian. We had a political conversation, and he told me that he was from Syria, so we exchanged our solidarities. But the first thing that was interesting — he went to study in Russia where he learned Russian. And his country then experiences Russian intervention and bombardments. Therefore, I'm wondering, how do Syrian people see Russia now?

The answer to this question depends on which Syrians you ask. Because Syrians who are affiliated to the regime will see Russia as an ally, although even within that camp there's concern over the external influence now, whether that's from Russia or Iran.

But for the rest of us, the majority, Russia is an imperialist power. It has intervened to support a fascist dictatorship to carry out a genocide against the Syrian people. Russian aerial bombardment has destroyed large parts of the country and specifically targeted civilian infrastructure, such as hospitals, in opposition-controlled areas. Russia has been rewarded for its support with lucrative contracts for oil and gas. The Russian company Stroytransgaz, owned by a Kremlin-linked oligarch, has been granted 70 percent of all revenues from phosphate production for the next fifty years. Syria has one of the world’s largest reserves of phosphates. Russian military bases have been established, and Russian national holidays are now ‘celebrated’ in Syria.

It's not only military support that Russia gives the regime, but also political. For example, on the international stage, Russia plays the role in Syria that the U.S. plays for Israel. Any motions that get brought before the Security Council or before the U.N. bodies are always vetoed by Russia. Russia gives that political protection to stop any means for international accountability or to go forward with a peace deal that is not on the regime's terms. Russia has been very active in trying to secure ‘peace agreements’, but they're not really peace agreements. They're trying to force capitulation of Syrians to the regime's terms.

You have mentioned that there are different Syrians and people of different opinions. And Syria is today largely associated with jihadism and sectarian struggle of all against all. But the Syrian revolution started as a mass democratic protest that actually united citizens of different ethnic backgrounds and confessions.

So how much of the current fragmentation and sectarianism of the struggle is due to the regime's ‘divide and rule’ policies, to the jihadists, and to the democratic opposition's inability to actually transcend prejudice and petty ambitions for broader solidarity?

Just to be clear about the structure of the regime: the Assad family comes from the Alawi sect, which is a minority within Syria. The majority of the population is Sunni Muslim, but there are also Shia, Christians, Druze and others. When the uprising started, it was a very diverse movement. It included men and women from all social backgrounds, all different religious and ethnic groups. There were a lot of attempts to not fall into sectarianism. At protests people were calling for unity among all Syrians, holding signs and banners that were making appeals to minority communities, etc.

On March 15, 2011, protesters in Deraa, Damascus, and Aleppo began demanding democratic reforms and the release of political prisoners. Brutal persecution and repression by the government followed. Image: Ali Haj Suleiman / Al Jazeera

Of course, a strong democratic, non-sectarian movement was the biggest threat to the Assad regime because it could gain support internationally. So the Assad regime had to sectarianize and Islamize the conflict. And it did this very deliberately — a sectarian engineering as it were. For example, in 2011-2012 at the time when the regime was rounding up all these peaceful pro-democracy protesters and detaining them, it released many Islamist extremists from prison. And many of those released went on to head some of the most hardline brigades that existed. For example, Hassan Aboud, one of the founders of Ahrar al-Sham, was released, and Zahran Alloush, the former leader of Jaysh al-Islam, as well as people who became big figures in Jabhat al-Nusra, which was the Al-Qaeda affiliate, and also in ISIS.

The reason the regime did this was to send a message to both an external and an internal audience. Externally, it wanted to say: look, this is part of the War on Terror, we're fighting Islamist extremists, you might not like me, but these guys with beards are ten times worse. Internally, it was sending a message to minority groups, to the Alawi community, to Christian groups: again saying, you might not like me, but the alternative is worse, and if these Islamist extremists come to power, minorities are not going to be safe.

So it was a tactic that worked both internally and on the international level. The regime also manufactured sectarian conflict by sending armed gangs from Alawi groups known as Shabiha into Sunni communities to carry out massacres. The idea was to provoke a response and to get Sunni communities to go into Alawi communities and Shia communities and also commit massacres. And occasionally that worked, there was a retaliation.

But exactly as you say — it's a ‘divide and rule’ policy. And sadly, today there are many minority groups that wouldn't necessarily support the regime, but feel safer to be on the side of the regime than with the opposition. And over time, especially due to Iran’s intervention, the conflict has become increasingly sectarian.

How did militarization affect the revolution? Were there alternatives?

First, I think it’s important to recognize that militarization was inevitable. The regime used mass violence against those who opposed it and people had to defend themselves and their communities. It became a struggle for survival. Peaceful methods of struggle are inadequate when a regime is prepared to use tactics of extermination against a civilian population.

A Free Syrian Army fighter runs for cover as a Syrian Army tank shell hits a building across the street during clashes in the Salaheddine neighborhood of central Aleppo on August 17, 2012. Image: Goran Tomasevic / Reuters

But militarization brings with it a whole host of problems. It sidelines civil activists, those working in their communities, who are the backbone of the revolution. It empowers war lords and authoritarian groups and it enables foreign powers (who provide weapons) to influence the movement – always in a way that serves their interests, not the interests of revolutionaries.

There was always an alternative – that was to provide support to the democratic opposition – those who were building alternatives to the regime in their communities, even under savage bombardment. Had these people received the solidarity they deserved, the military aspect would not have become so dominant and the civil resistance would have had more strength.

What is the role of the left in the Syrian revolution? I know there are many prominent voices such as Yassin al-Haj Saleh, Riyad al-Turk, Omar Aziz. What can you say about the left?

There wasn’t a large, independent, organized left within Syria for two reasons. Firstly, the Assad regime repressed any independent leftists, they ended up in prison or fled the country. The regime then co-opted a large section of the traditional left, the Syrian Communist Party, that later joined the government in the National Progressive Front. This is a coalition of different parties, however by and large it is just an image with no real participation in it — everything is controlled by the Ba'ath Party and the president. Secondly, the structure of the Syrian economy was a factor in the absence of unions and the formation of a working-class culture and politics as most work places are small family run businesses.

So there wasn't really a strong independent, organized left base to start from – apart from Riad Al-Turk’s party which split from the Syrian Communist Party and some other smaller and Kurdish parties which were persecuted. When the revolution happened many young leftists who were part of the Syrian Communist Party quit and joined the revolution. They were very outspoken that their alleged leftist comrades (both in Syria and internationally) betrayed Syrians and the people’s struggle. There are a number of smaller independent groups and then influential individuals such as the writer and intellectual Yassin Al Haj Saleh and Omar Aziz, who was the ideologue behind the idea of the Local Councils which were established to self-govern opposition held territory. Omar Aziz ended up being arrested and died in prison, and Yassin Al Haj Saleh fled the country and now lives in exile.

Do you think this situation with the unorganized left in Syria could be the reason for the lack of solidarity and support for the Syrian revolution on the part of the American and European left?

It could be a factor. But plain ignorance is also a factor. For example, a few years ago trade unionists and ‘leftists’ from around the world travelled on a solidarity mission to Syria in support of the regime. They seem to be completely unaware that independent leftists are repressed and independent trade unions are non-existent!

The western left as a whole has failed to support Syrians in their struggle for freedom. Part of this is because of the problem of ‘campism’ which has become dominant in leftist thought. These so-called ‘anti-imperialists’ believe that the only imperialist powers are the US and the west, they fail to see that other imperialisms actually exist, such as Russia and Iran. They have therefore supported the regime, seeing it, incorrectly, as a bulwark against western imperialism. They failed to listen to Syrian voices on the ground and spread all sorts of misinformation about what was happening, even denying chemical massacres were carried out by the regime and absolving it of any accountability.

Displaced Syrian residents wait to receive food aid distributed by the UN Relief and Works Agency at the besieged al-Yarmouk camp, south of Damascus, Syria, on January 31, 2014. Image: UNRWA / Reuters

Sounds very familiar in Ukrainian context.

Supporters of the Syrian revolution also usually express solidarity with Palestinians and you also signed a letter in support of Gaza. What is the relationship between supporters of a democratic Syria and Palestinians, and especially considering that some of the Palestinian left are engaged in campism?

Since October the 7th, we've seen so many attempts by Syrians to reach out to Palestinians and show solidarity. Not only statements, but at the regular Friday demonstrations against the regime, people carry Palestinian flags and have decorated walls with murals in support of Palestine. In Idlib city, they've renamed a central square Gaza Square and decorated it with the Palestinian flag.

Syrians feel a lot of affinity with people in Palestine. We are connected, historically, as people from Palestine, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon were all united in Bilad al Sham, our culture is very similar. In addition, the occupation of Palestine is a central issue for Arabs and Muslims, because of the extent of the injustice there and because our regimes have used the Palestinian cause as a way to bolster their support among their own populations.

Palestinians have also stood in solidarity with Syrians since the outbreak of the revolution – I saw this myself, especially among people in Gaza when I was there. However, there are also many Palestinians that have fallen into campist politics. Many prominent voices on Palestine, especially among people in the west, have slandered and discredited the Syrian revolution, essentially supporting the regime. At the protests for Palestine now happening on US campuses we see people holding the flag of the Iranian backed Lebanese militia Hezbollah seeing it as part of the resistance to Israel. Hezbollah has actively participated in the genocide against Syrians – it implemented starvation sieges on opposition communities similar to what Israel is doing now in Gaza. These are not allies for liberation.

Our solidarity must be based on common principles not on which states are participating in a conflict. It must be based on people’s struggles for freedom and social justice otherwise it is meaningless. As the statement you referred to earlier from revolutionary Syrians in support of Palestine said; ‘mutual and intersectional solidarity is essential, our struggles are one, our freedom each depends on the freedom of the other.’

Girls break their fast amid damaged buildings during a Ramadan iftar organized by an NGO, Douma, 20 June 2017. Image: Bassam Khabieh

Could you tell a bit more about the Arab left-wing camp?

Traditionally there are three main political currents in the Arab world; Islamism, Arabism/nationalism and leftists. Many growing up who didn’t feel represented by Islamism or the Arabism of the nationalist regimes (such as minority groups in Syria) became leftists.

There is a similar divide as to what you see on the global left. The traditional Arab left fell into a similar campist politics where US imperialism and Israel are the ultimate enemy. Many of these supported the dictatorship of Assad – seeing it as part of the ‘axis of resistance’. Of course, there were always exceptions, those who were anti-authoritarian leftists, such as those in the Communist Party of Riad Al-Turk who we previously mentioned and who fought for democracy and civil liberties. Yet there is also a new generation which has grown out of the revolutions and has a much more sophisticated analysis that corresponds with the reality of the world we are living in – one of competing imperialisms and who stand against all oppressors and stand with all struggles for dignity. I have a lot of hope in this new generation even though we have lived through a violent counter-revolution and are currently defeated, unorganised and traumatised.

How has the Russo-Ukrainian war affected Syria?

There has been so much solidarity and support from Syrians to Ukrainians, and the other way around, it’s been beautiful to see. I think we very much identify with each other’s struggles for a number of reasons. We both have a common enemy in the Russian state, we have both gone through popular uprisings, before entering a conflict situation and we have both had to deal with some of the campist politics we’ve been talking about – where our struggles have been discredited and our enemies supported. This, and our collective trauma, has brought us together. Many Syrians have travelled to Ukraine on solidarity missions, and at the beginning of the conflict, reached out to give practical advice – such as on how to protect themselves from ‘double-tap’ strikes which is a favourite tactic Russia uses to kill as many civilians as possible (after a bombing, Russia again bombs the area once rescue workers have moved in). And I’ve got to know many Ukrainians through their solidarity with Syria. Syrians celebrate when they see Russian generals, who were previously involved in war crimes in Syria, being killed in Ukraine – it’s a small taste of justice for us. We hope that Ukraine will one day be free from Russian imperialism as we hope Syria will also be free.

But on the broader level the Russo-Ukrainian war did not affect Syria so much. Russia did have to withdraw some troops from Syria to move them to Ukraine but it didn’t make much difference given the timing, when most of the big battles were already over.

Russian military in Syria. Photo: TASS

We try to prove in the global discourse why it is important to defeat Russia, notably because Ukraine is not the first one attacked by it. Before there was Syria, Georgia, Chechnya. So one could circumscribe an invasion pattern. Thus we could build solidarity around the anti-imperialist argument that defending and aiding Ukraine entails defending and aiding Syria and vice-versa. Do you see this happening?

We definitely need to push this forward — there's such an absence of understanding of Russia as an imperialist power, not just today but historically. There's a complete lack of knowledge amongst westerners of Russia's historical role; you only need to look at the map at the size of Russia to know that this is a state that was created on colonial conquest. Unless we challenge people’s world view – where the western world is at the centre of everything- we will be unable to respond to some of the challenges we currently face globally.

From the outside, it looks like the Syrian revolution is a lost cause, but in August last year, there was a new wave of protests in southern Syria. How do you assess the current situation and the hopes that Assad can finally be overthrown?

In parts of the country which are not under the control of the Assad regime, such as the province of Idlib and parts of northern Syria, weekly protests against the regime have continued since 2011 until today. This shows that people still have not given up on the values and demands of the revolution.

Since August, there has been an uprising in the southern province of Sweida. This is interesting because Sweida is a majority Druze population, and its people adopted a position of neutrality when the revolution began. They didn’t join the revolution, but neither did they stand with the regime. However, the living conditions deteriorated so much over the past few years as the economy has collapsed and this made people go to the streets in protest. And now they are clearly calling for the fall of the regime, and identify with other areas of Syria which are struggling for freedom – we hear chants in solidarity with Idlib and vice versa – and there have been many assaults on offices of the ruling Baath Party and regime positions. As they are a minority group, the regime did not respond with the mass violence and arrests we saw elsewhere in Sunni majority areas – for the reasons we spoke about before – that the regime wants to portray itself as a ‘defender of minorities’ – so the protests have continued until today.

Also in northern Syria in recent months there is an uprising against Hayat Tahrir Al Sham, which was formally Jabhat Al Nusra. This is an authoritarian Islamist militia which has a lot of power and governs parts of the north-west of the country. It is very clear that Syrians reject all forms of authoritarianism – whether it is the regime, or any other group. The struggle is still one for freedom and democracy.

Members of al-Qaeda's Jabhat al-Nusra gesture as they drive in a convoy touring villages, which they said they have seized control of from Syrian rebel factions, in the southern countryside of Idlib. Image: REUTERS / Khalil Ashawi

You were writing for so many years about the Syrian revolution, which looked more and more hopeless.

I was heartbroken when I read your book because it seems like there is nothing that can be done, and also Syrians don't have as much support on the international arena as Palestine, for example, or Ukraine. How do you personally survive all these years without despairing? I think for Ukrainians, we need insights of this kind.

The past few years have been so traumatic for Syrians. Our country has been destroyed, and our loved ones detained, killed or displaced. Those in exile face hostility, violence and even the threat of forcible return to Syria. And now the world is normalising with the tyrant who created our misery. It’s hard at times to have the strength to keep struggling, but what can we do? The situation continues and so must we.

Syrians on the ground haven’t abandoned their struggle. So those of us on the outside must continue to support them, to raise awareness of what’s happening in Syria. We have the luxury of distance and space to breathe. And most importantly, we are able to organise, to build connections with people in struggle elsewhere – as we are trying to do with this conversation.

Over the past decade and a half, I’ve made connections with people from all over the world. Many of whom feel excluded from the dominant left discourse for many of the reasons we have spoken about. This gives me a lot of energy, to connect with others, to work in community with like-minded people, to try and build a new vision for internationalism, amongst those from the peripheries, one that is focused on people, not states and is against all authoritarians and all imperialisms. Hopefully, in the future we can build a new movement together.

Talked to Leila: Maria Shinkarenko

Spanish translation: entendiendoucrania.com

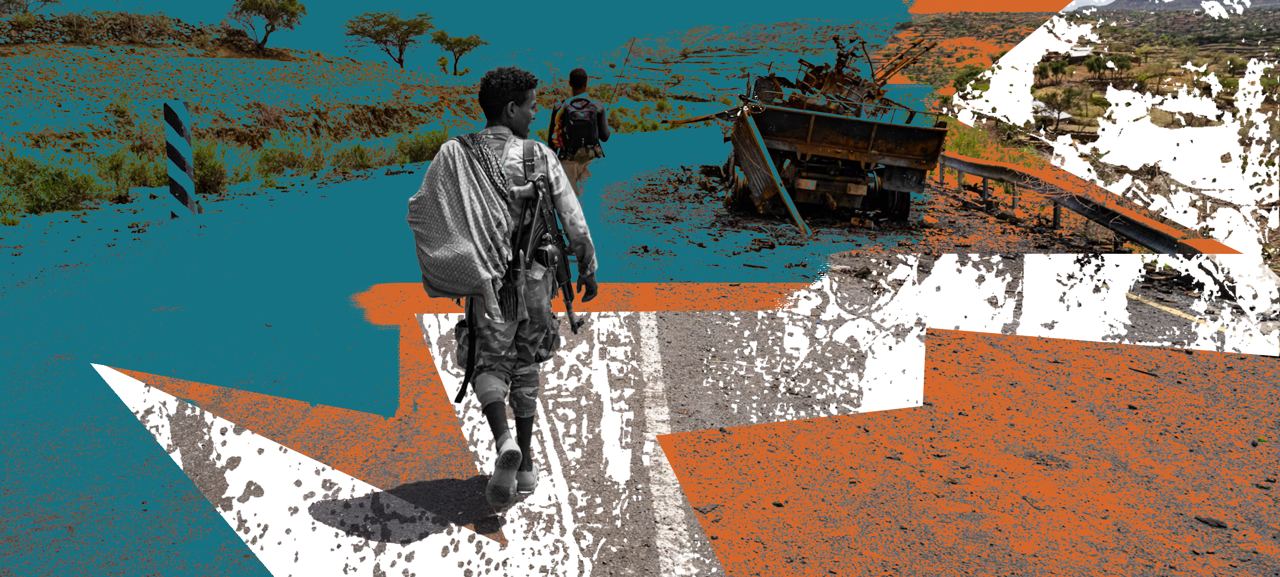

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva