Mariupol Memory Park is a project of the Freefilmers collective, one of the many artistic and research communities of Mariupol that united people who lived and worked in the city. The project functions as a website that absorbs the reflections and creative output of Mariupol residents, their accounts of the struggle to assert the right to the city as well as attempts to examine the space of the city before, during and after the urbicide[1] it underwent. The project presents a vision of Mariupol’s cultural landscape that in all probability would not have been deemed worthy of preservation by major cultural institutions and the dominant culture itself.

I have never been to Mariupol. It seemed too far from my hometown: 14 hours on the train to Mariupol always seemed too much. Now, it takes me twice as long to get home from the place where I live. I only know Mariupol through the memories and impressions – often conflicting – of my acquaintances and colleagues: some talk of their love for its landscape and people, others of pollution and acid dust in the air made it impossible to breathe. Such contradictions are probably familiar to many residents of post-Soviet Ukrainian cities, places that we love and hate at once, places that are hard to imagine without their ghosts and concrete ruins.

A work from the photo series Mariupol, Summer 2022 by photographer IF69 (Pictures for the Last Trolleybus to the Livoberezhnyi District section of the website)

“Our experience continues to exist, and we can interpret it, keep it alive and nurture it”

The team behind the Mariupol Memory Park website started working on it in May 2022, when project participants realised that Mariupol’s cultural, social and economic context was destroyed. However, everyone agreed that they wanted to talk about their experiences through creative means: not just to publish the surviving photo albums or family archives in order to preserve them, but to reflect, to create something new while working on their parts of the project. “We understood that the city had been destroyed, but people remained, and they could take an active part in creating the archive”, says director Sashko Protiah, a member of the Freefilmers community. “It felt important to do some actual work instead of simply collecting information”.

Since the beginning of the war, in the face of destruction wrought on museums, cinemas, libraries and other cultural hubs by Russian bombs, Ukrainians have been creating databases and online archives. It’s a dynamic process that to a large extent relies on grassroots efforts. Seen against the backdrop of attempts to destroy one of the few physical Ukrainian archives – the Dovzhenko Centre[2] – it feels even more noteworthy. Before the start of the war, I had worked on creating an archive of Ukrainian Soviet cinemas. The project aimed to make what was being destroyed visible in a situation where all other means of stopping the destruction were of no use. All these projects, as if seized by archive fever[3], are united by a practical vision of the archive as an established database of relatively objective knowledge where classification becomes a tool to save (or at least draw attention to) objects that are being systematically destroyed.

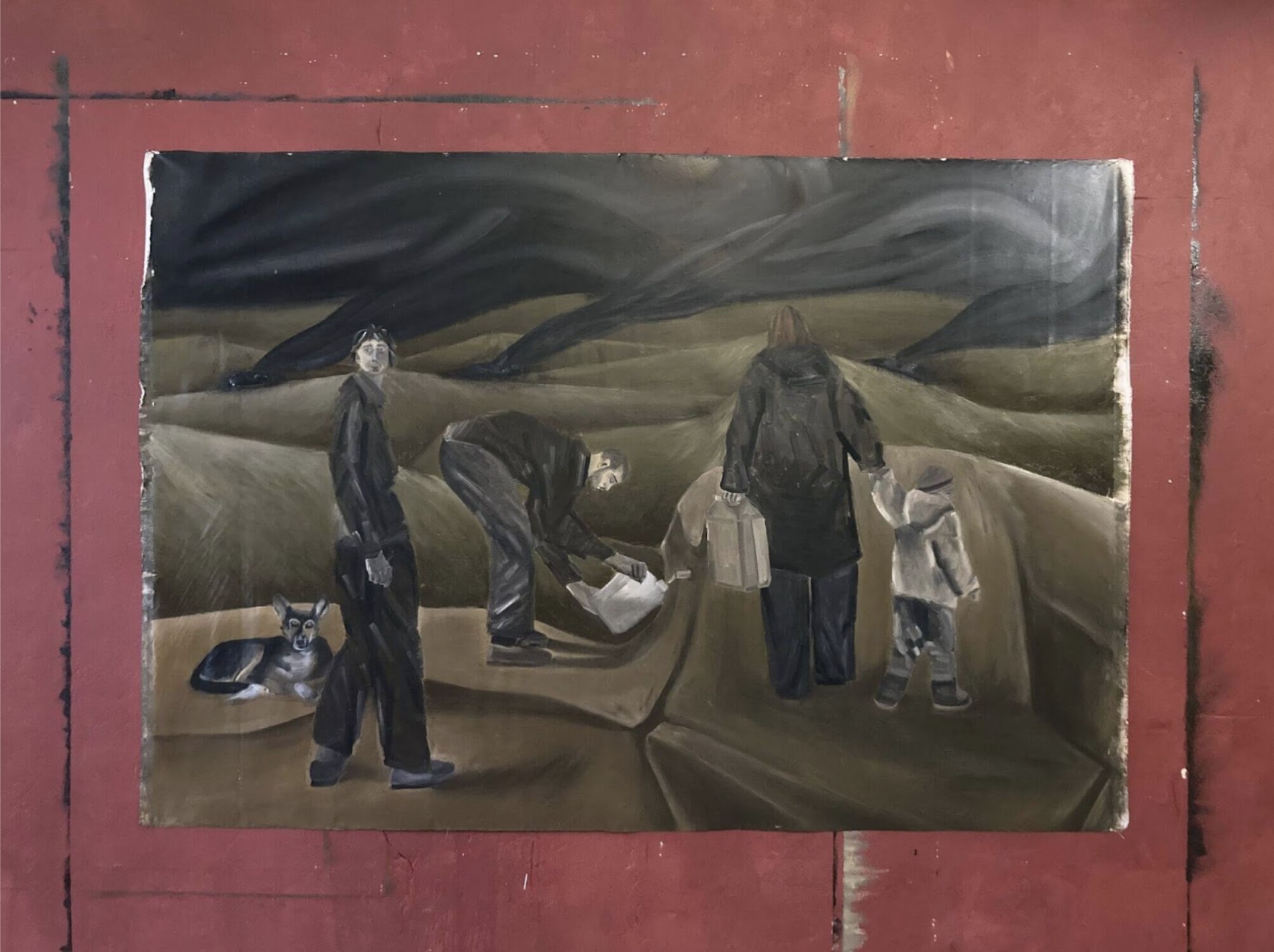

A work from the series War by artist and director Vasyl Liakh, (Pictures for the Last Trolleybus to the Livoberezhnyi District section of the website)

A work from the photo series Forever Gray by Bohdan Ugly (Pictures for the Last Trolleybus to the Livoberezhnyi District section of the website)

That’s not the aim of Mariupol Memory Park; the project does not attempt to return to a lost home or to prove a crime committed against the city and the people who lived there. The site is a safe space for reflection and preserving the memories of things that would never end up in the classic archives of big institutions. The project team provides a space for elusive experiences as opposed to generic symbols that, the team believes, risk oversimplifying the way we remember cultural landscapes, creating an immovable and narrow vision of historical events[4]. “Mariupol Memory Park is about things – however strange and ambiguous they are – that constitute important details within the emerging corpus of memories”, says Sashko Protiah.

Autonomous anarchive

As the project reverses the classical archiving paradigm and opposes the hegemonic discourse, the members of the team call it anarchive. Positioned somewhere at the intersection between Jacques Derrida’s critique of the “archive fever” (mal d’archive) and Michel Foucault’s concept of archaeology, the concept has taken root in media theory, where it refers to practices that undermine the colonial past of archives, propose a more anarchic vision of the archive, evolve with the emergence of digital archives and involve intuitive research, artistic and activist approaches (2). While traditional archives are fixated on artifacts, anarchives work with collective memory and discourse, thus turning archiving into a never-ending creative process.

Mariupol Memory Park seeks to reproduce Mariupol’s democratic cultural landscape that, according to the project team, was really inclusive. In Mariupol, project participants emphasize, they felt like they could be together regardless of social boundaries and status: it did not matter whether you worked at a factory or regularly travelled abroad to present your work there. They also describe local environment as “a mishmash of artists and activists”. Nychka Lishchynska, the editor of the website and the author of the text “I Don’t Feel Sorry, I Feel Tenderness” from the A Displaced Library section of Mariupol Memory Park, notes the importance of the unintentionality as a method behind the project. Unintentionality, Nychka feels, permeated her life in Mariupol; thus, she wanted to imbue her work within the project with the same spirit.

Talking about classification practices and how they pervade and define society, Susan Leigh Star and Geoffrey C. Bowker point out that classification – as a spatial, temporal or spatio-temporal segmentation of the world – is manifested in archives. Therefore, each classification system, in their opinion, is just a set of boxes (metaphorical or literal) into which things can be put to then do some kind of work, bureaucratic or knowledge production (3). Mariupol Memory Park does not seek to classify photos of Mariupol and testimonies of life in the city or systematize and recreate books from its lost libraries.

Another concept that resonates with the anarchive is that of the “autonomous archive”. According to researcher Lawrence Liang, the autonomous archive realises the potential of the archive as virtuality and opposes conservative approaches to archiving characterized by paradoxical “blackmail of memory and amnesia” (4). Autonomous archives, like Mariupol Memory Park, focus on co-creation instead of representation. They do not make objective generalisations; rather, they explore details, their attention dispersed among a number of things under consideration, and take a stance. “The production of a concept is a provocation, a refusal to answer to the call of the known, and an opportunity to intensify our experiences… The naming of something as an [autonomous – K. R.] archive is not the end, but the beginning of a debate” (4).

The search for new practices of creating archives does not re-appropriate state archives or deny them a right to exist. It is aimed at reinventing the concept of the archive. Henri Langlois, a pioneer of film archiving and a co-founder of the Cinémathèque Française, formulated an important idea regarding the artifacts that anarchives work with. Explaining his approach, he said that “films are like Persian carpets, they have to be walked on” (4). This phrase contributed to an alternative vision of archives, and not just those focused on film preservation. Mariupol Memory Park, one of such alternative archives, combines different media. It doesn’t set out to collect all possible memories or artifacts as objective evidence of the city’s history. By archiving, the project preserves different visions of Mariupol, and, more importantly, gives them an opportunity to continue living and generating new ideas.

The components of the project

The website includes three main parts, some of which will be gradually expanded after the launch of the project: A Displaced Library, Three Stories About Bings, which you can listen to to as audio tracks, the online exhibition Pictures for the Last Trolleybus to the Livoberezhnyi District. Soon, the site will also feature Two Films for the Pobieda Cinema. All of these sections immerse site visitors into Mariupol landscape. Importantly, though, they refuse to imitate its space or blindly follow its outline; instead, they create their own narratives.

Masha’s and Denys’s tattoos: A Dry Bouquet from the Premises of a Plant in Mariupol and Vagina, Ptichka the cat and Contour of the Map of Mariupol (Pictures for the Last Trolleybus to the Livoberezhnyi District section of the website)

The non-narrative approach is manifested in one aspect only: the visual solution found for the website by its designer Nastia Teor. Her design binds the elements of the Park together but does not romanticize the resulting space, revealing faultlines in the construction of the space of Mariupol itself. The green colour refers to a kind of greenwashing inherent to the idea of Mariupol as a garden city. The project team believes that this city planning concept was used as a façade where real solutions to the problem of pollution (of air, sea and surrounding area) by local enterprises were needed. That’s why the colour you see on the website is not bright green: it looks faded, as if covered with the dust that wind blows into the city from the slag heap on the territory of the Azovstal plant.

Mariupol Memory Park texts, audio stories and visual works examine various elements of Mariupol’s cultural and spatial cityscape. The authors establish a connection to its key landmarks (the slag heap, also known as Shlakova Hora; the Pishchanka beach; the sea; the tram route) and explore the cultural or everyday phenomena that matter to them (communities, events, ruins, the tram schedule).

A work from the photo series By the Sea by director Zoia Laktionova (Pictures for the Last Trolleybus to the Livoberezhnyi District section of the website)

“Strictly speaking, there are no bings in Mariupol”. However, the slag heap on the shore of the Sea of Azov is one of the defining features of the city’s spatial arrangement, and it is often mistaken for a bing. This element unites three stories – by Masha Pronina, Sashko Protiah and Alisa Oleva – about bings in Donetsk, Toretsk and Mariupol. Bings tower over the landscape of many industrial Ukrainian cities and subtly yet persistently remind local residents they are there to stay with particles of poisonous dust. “It’s the reverse side of the modern extractivist economy, an embodiment of absolute waste, a place where you just wander without making any connections”, says Sashko Protiah. “By default, you are expected to be a consumer, but once you find yourself in this landscape made of nothing but slag, you slip through the net of the capitalist system”. By telling us about a dangerous pastime – walking through these toxic elements of landscape – the three stories reveal the role of bings in the space of industrial cities and how strongly they are connected with the lives of local people.

Pentagon District by photographer Bohdan Ivaniuk, from the series The Air of Forgotten Dreams (Pictures for the Last Trolleybus to Livoberezhnyi District section of the website)

These audio stories have also found a spatial dimension beyond the website. Thanks to the team’s Scottish colleagues, Diana Vonnak and Victoria Donovan from the University of St. Andrews, they became part of the soundtrack to a walk across a similar landscape in West Lothian, where heavy industry has also created industrial waste piles. Locals call them bings, and this actually determined how the Ukrainian word terykon was translated into English on the website of the Mariupol Memory Park.

Language plays an important role in shaping the narrative of the site as a whole and establishes connections between different elements of the cultural landscape that are often not immediately clear. The texts play with words, which, according to the project team, was an important trait of everyday life in Mariupol. Thus, hybrid words appear in titles: for instance, the Ukrainian name of the library section, Biblioteka Pereselenky (A Displaced Library), reminds readers of the Korolenko Library, the central Mariupol library that suffered extensive damage when the war escalated. The site itself is available in two languages: Ukrainian and English. Its Ukrainian-language version, however, contains texts in Russian as well as those in surzhyk, a mixture of Ukrainian and Russian. In such a way, the project reappropriates these language forms rather than rejecting and victimizing them; after all, they are part of the experience of living in the city and naming it.

***

Mariupol Memory Park is a set of practices that do not stigmatize the post-colonial and post-socialist experiences of Ukrainian cities and reveal the devastating consequences of Russian imperialism as well as the crises Ukrainian cities faced when they encountered another type of colonialism, the Western one.

As I reflected on these grassroots archival and memory practices, I thought of Aleida Assmann’s article “The Crisis of the Future and the Reinvention of the Past” written for the 2017 Guidebook of the Kyiv International. Today, I no longer read it as a warning about the consequences of instrumentalizing the past and history. In the article, Assmann once again refers to the works of Reinhart Koselleck and talks about his differentiation between the concepts of “present past” and “pure past”. “The present past is saturated with personal memories and collective emotions through which the living are still involved in and bound up with the past” (1). These strategies are a way of mastering the past, and only after their disappearance does the past become the domain of historians as the side of the unbiased and cold (1). While in some places archiving practices try to create objective archives and even speak of “recording and preserving history thoroughly”[5] right here and now, Mariupol Memory Park is aware that this past is still the present past. Therefore, the project leaves space for a future where history is no longer an instrument of imperialism and violence.

*“The ruins have taught me something about myself” – a quote from Nychka Lishchynska’s text “I Don't Feel Sorry, I Feel Tenderness” on the Mariupol Memory Park website, in the section A Displaced Library.

Bibliography

1. Assmann, Aleida (2017), The Crisis of the Future and the Reinvention of the Past. Guidebook of the Kyiv International. Kyiv, Meduza. pp. 25–44.

2. Dekker, Annet (2019). Between Light and Dark Archiving. in: Hoth, J. and Wandl-Vogt, E. (ed.) Digital Art through the Looking Glass. p. 74.

3. Bowker, Geoffrey C., Susan Leigh Star (2000). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 10.

4. Liang, Lawrence (2016). The Dominant, the residual and the emergent in archival imagination. in: Artikişler Collective (Özge Çelikaslan, Alper Şen, Pelin Tan) (ed.) Autonomous Archiving. pp. 97–115.

Footnotes

- ^ The concept of urbicide became widely used during the Bosnian War of 1992–1995 to describe the large-scale deliberate destruction of cities as a special form of violence. Of course, the phenomenon of urbicide predates the introduction of the term; in particular, urbicide accompanied the Allied counteroffensive during World War II.

- ^ The Dovzhenko Centre (Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre) is a Ukrainian state institution that preserves film, paper archives and museum collections, conducts research and organises exhibitions about Ukrainian film heritage. The Dovzhenko Centre is the largest Ukrainian film archive, which, however, does not have the official legal status of an archive. Ukrainian government is using this issue and making other manipulative claims to sabotage the work of the Dovzhenko Centre and dissolve this institution. You can find more information about the situation here.

- ^ Archive fever (Mal d'archiv) is a work by Jacques Derrida where the author points out that “fever” and disease are embedded in the very nature of the archive. In societal life, this is manifested in the desire to own the archive, not just use it. On this, see also Carolyn Steedman's “Something She Called a Fever: Michelet, Derrida, and Dust”.

- ^ Here and in the rest of the text, I use information from interviews with the team of the project.

- ^ A phrase taken from the title of the presentation of the “War Archive” project by NGO Docudays (“War Archive. Recording and Preserving History Thoroughly”).

Author: Ksenia Rybak

Translated from Ukrainian by Olesya Kamyshnikova

Title photo: Kateryna Gritseva, Selasata. The Goddess of the Abandoned Fish-Canning Shop (Pictures for the Last Trolleybus to the Livoberezhnyi District section of the website)