At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, socialist views were more the norm than the exception among the younger generation of Ukrainian cultural and political figures. Many Ukrainian activists of the first half of the 20th century gained their first experiences in political participation, journalistic writing, and encounters with police repression within the socialist movement. However, not all of them remained lifelong socialists; some eventually gravitated toward the opposite end of the political spectrum. One example is Dmytro Dontsov, who began his long political journey as a member of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Workers’ Party and ended it as a Christian traditionalist and ultra-conservative conspiracy theorist.

Over a hundred years ago, in 1922, Dr. Dmytro Dontsov did the same thing as the author of these lines: he wrote and published a text for the anniversary of Lesya Ukrainka, an essay titled The Poet of the Ukrainian Risorgimento. By that time, he had already abandoned Marxist views and was gradually formulating the idea of “active nationalism,” which was based on the rejection and condemnation of socialism, rationalism, materialism, and democracy — in other words, a complete break with the ideas he himself had once embraced. He had, however, retained a respect for the works of Lesya Ukrainka and Taras Shevchenko since his youth. Yet this respect was rather peculiar, as he positioned these authors in opposition to the entire preceding tradition of Ukrainian social and political thought, which he disdainfully referred to as “Provencalism.”

Lesya Ukrainka

In Dontsov’s imaginary, Lesya Ukrainka appears as a “typical figure of the Middle Ages” — a fanatic, a voluntarist, a proponent of militant nationalism, for whom the very idea of internationalism was “infinitely alien” (Донцов 1922: 4, 17).

The interesting point is not that Dontsov projected his own worldview onto Lesya — debating a long-deceased ultraright ideologue is not the purpose of this text. Rather, what stands out is that the “final boss” in his struggle against “Provencalism” was Mykhailo Drahomanov, whom he saw as embodying all the views he despised: socialism, secularism, rationalism, universalism, federalism, and faith in social progress. In reality, however, Mykhailo Drahomanov was not just Lesya Ukrainka’s uncle; she was so attached to him that she kept a handful of soil from his grave as a relic (Одарченко 1954: 39). He played a significant and positive role in shaping her worldview, and in many ways, she was his ideological ally. While her uncle was the publisher of the first Ukrainian-language socialist journal Hromada, Lesya became a co-founder of the first Ukrainian social-democratic organization in the Russian Empire. Thus, attempts to pit Drahomanov against perhaps his most famous follower are, at the very least, misplaced.

Although Lesya Ukrainka was Drahomanov’s student, she was not bound to remain within the confines of his ideology for life. The goal of this article is to trace the evolution of Lesya Ukrainka’s political views based on her non-fiction writings — her correspondence and journalism.

Between Two Empires and Two Socialist Traditions

Lesya Ukrainka began taking a serious interest in socio-political issues at the turn of the 1880s and 1890s — a difficult period. The Ukrainian movement had been weakened by the 1876 Ems Decree, the exile of some activists, and the forced emigration of others, including Mykhailo Drahomanov. This was compounded by the stabilization of autocracy under the rule of Alexander III (1881–1894), which was accompanied by the suppression of both real and potential revolutionary forces.

Those Ukrainian activists who did not go into exile or flee abroad focused on apolitical cultural activities, carefully avoiding statements or actions that could provoke government repression. To young, politically engaged Ukrainians, such apolitical cultural activism seemed overly cautious and timid. Moreover, as Ivan Lysiak-Rudnytsky rightly pointed out, this approach represented a clear step backward compared to the activism of the previous decade (Лисяк-Рудницький 1994: 183).

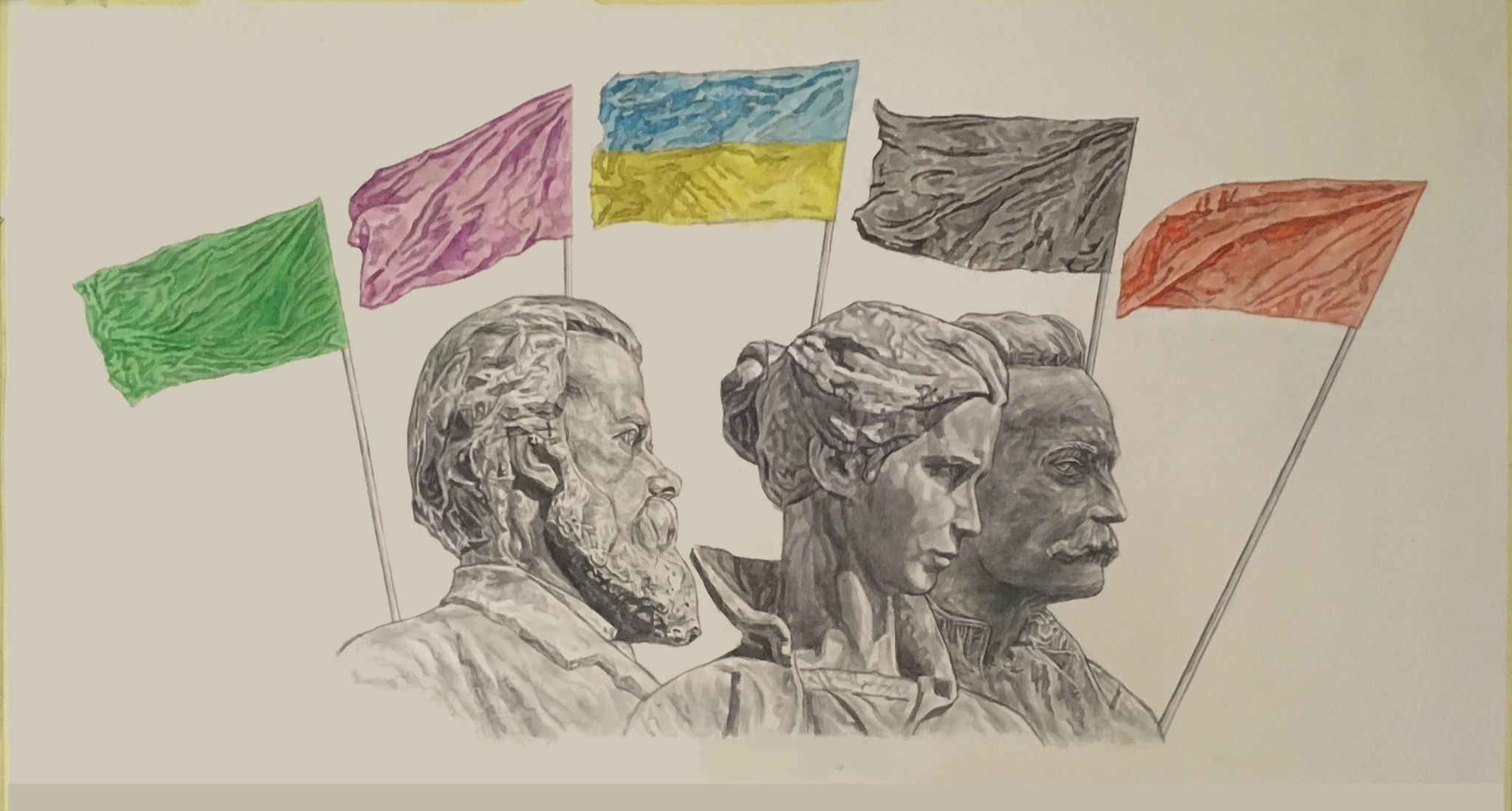

Mykhailo Drahomanov

Mykhailo Drahomanov was the main inspirer and ideologist behind the politicization of the Ukrainian movement at that time. After emigrating, he did not abandon political activism and published the journal Hromada in Geneva, while also maintaining close ties with senior members of the Kyiv Hromada. However, Drahomanov’s politicized appeals, expressed in socialist rhetoric, seemed too harsh and reckless to the cultural activists, known as “kulturnyky,” who feared potential government retaliation. As a result, by the mid-1880s, ties between Drahomanov and the Kyiv Hromada were severed, and the Hromada ceased its already unstable financial support for his publishing projects (Федченко 1991: 253–256). Drahomanov continued to maintain friendly relations with individual “kulturnyky” from Dnieper Ukraine who had not cut ties with him, but he no longer placed hope in the older generation of Hromada members and instead relied more on the youth.

Under the influence of literature from Geneva, circles of Drahomanov supporters began to emerge among educated Ukrainian youth. Consequently, the youth split into “kulturnyky,” who remained aligned with the Old Hromada community, and “politicians.” The key figure in creating and supporting the “politicians’” circles was Mykola Vasylovych Kovalevskyi — a compatriot, like-minded associate, and friend of Mykhailo Drahomanov since their high school years. Together, they had stood at the origins of the Kyiv Hromada in the 1860s. During the subsequent conflict, Kovalevskyi broke with the Old Hromada and began raising funds across Ukraine to support his emigrant comrade (Яковлєв 2013: 162). Hanna Kovalevska, Mykola Vasylovych’s daughter and a close friend of Lesya Ukrainka, also played a significant role in spreading Drahomanov’s ideas among the youth.

Cover of the Hromada journal, 1881

The organizational successes of the Galician radicals had a profound impact on Kyiv’s “politicians.” Influenced by Drahomanov and led by his students Ivan Franko and Mykhailo Pavlyk, they launched the journal Narod in 1890 and founded the Ruthenian-Ukrainian Radical Party. Drahomanov’s supporters in the Russian Empire looked with hope toward the struggles of their Galician counterparts, believing that the Galician radical movement would eventually spread to Ukrainian lands under Russian rule. Mykola Kovalevskyi regularly raised funds to support Narod, where young Dnieper Ukrainian supporters of Drahomanov began to publish their works (Тучапский 1923: 30–34; Грінченко 1925: 124; Яковлєв 2013: 163).

Participants in the Drahomanov circles primarily engaged in self-education, but they increasingly sought to move toward practical action. However, their vision of how to achieve this remained vague. Drahomanov’s ideas about organizing local councils and mobilizing the peasantry seemed unrealistic in the context of the repressive police state that Russia had already become. Meanwhile, Marxism was making its way into the Russian Empire, shifting the focus from the peasantry to the working class, which was much easier to agitate and organize. Among Kyiv’s educated youth, Marxism first spread within the Polish student community, which had better access to relevant literature. Among non-Polish students, Bohdan Kistiakovsky was the first to promote Marxism, having been introduced to it by Polish students at the University of Dorpat, where he had enrolled after being expelled from Kyiv University for illegal activities associated with the Drahomanov movement (Білоус 2017: 54).

At this time, many Ukrainian students with leftist views, frustrated by the passivity of Drahomanov’s circles, joined the broader Russian socialist movement. Later historians often tended to oversimplify the interaction between Ukrainian and Russian socialists, claiming that “the younger generation did not continue the path initiated by Drahomanov, but instead adopted ready-made formulas of international socialism from Russian sources.” Even the thoughtful and balanced historian Ivan Lysiak-Rudnytsky was not entirely free from such simplifications (Лисяк-Рудницький 1994: 188). In my opinion, the case of Lesya Ukrainka, along with that of many of her contemporaries, suggests that this conclusion is not entirely accurate. Drahomanov’s ideas were neither rejected nor forgotten, and not all young socialists of the Ukrainian fin de siècle were bound to Russian interpretations of socialism. Moreover, this applies not only to activists within Ukrainian socialist organizations but also to those Ukrainians who eventually joined all-Russian leftist parties — figures who are now often dismissed from the Ukrainian national movement, if not from Ukrainian national identity altogether.

The Niece of Her Uncle

The significant influence of Mykhailo Drahomanov on the philosophical and political views of Lesya Ukrainka is recognized by the overwhelming majority of researchers and commentators on her life and work, with the possible exception of followers of Dmytro Dontsov. Lesya Ukrainka’s correspondence with Drahomanov began in June 1888, and for a long time, their acquaintance remained primarily epistolary due to Mykhailo Petrovych’s emigration and his inability to return to the Russian Empire. Apart from the Kosach family’s meeting with Drahomanov in Kyiv before his emigration in February 1876, Lesya first met her uncle in person in Sofia in the summer of 1894, about a year before his death (Косач-Кривинюк 1970: 28, 69).

The Drahomanovs and the Kosachs, 1890s

However, even through her correspondence with her uncle, Lesya Ukrainka had much to learn. Drahomanov had considerable experience in communicating with his younger followers, and this experience was varied. He saw great potential in his niece and did everything he could to help her avoid the mistakes made by other Drahomanov supporters. Already in the first letter from Drahomanov to Lesya that has survived, dated December 5, 1890, he urged her to “critically look at ‘homegrown wisdom’” (Драгоманов 1924: 189).

The “homegrown wisdom” of Ukrainian circles, which remained isolated within their own ideas and operated within the Russian context, contrasted sharply with the ideas of Europeanism: “We have no other tasks, except those which exist in Europe; there are no other methods. The only difference is in quantity, not quality… It is the same science, and the same goal. Well, take up science, and then follow its example” (Драгоманов 1924: 195). A concise definition of Drahomanov’s principle of Europeanism was later provided by Mykhailo Drai-Khmara, who identified two dimensions of this concept: “joining oneself in a broad sense to European culture” and viewing national affairs within the pan-European context (Драй-Хмара 1924: 28).

Lesya Ukrainka and Ariadna Drahomanova, 1895

Drahomanov’s negative attitude toward “narrow nationalism” is also reflected in his idea of cosmopolitanism. He did not share the view of national nihilism; therefore, his understanding of cosmopolitanism differs from the conventional one and is closer to the concept of universalism — the belief in certain truths and principles common to all humanity.

For Drahomanov, such principles existed and had a supranational character, rather than being non-national or anti-national. This is why his idea of cosmopolitanism involves the equal interaction of different nations without the suppression of one nation’s development for the benefit of others. He did not reject the importance of developing national cultures; at the same time, he opposed national autarky, self-sufficiency, and isolationism. Instead, he proposed grounding national movements in universal human principles — hence the origin of his slogan: “cosmopolitanism in ideas and goals, nationality in the ground and form of cultural work” (Драгоманов 1894: 68).

Meanwhile, Drahomanov discussed issues of socialism with Lesya. In his letters to his niece, the ideologue of the Hromada socialist movement expressed his views on social democracy: “Social democracy is not in final ideals, but in the organization of workers, raising issues such as an eight-hour workday, and in opposition to militarism, especially in Germany” (Драгоманов 1924: 195–196). This thought clearly echoes the famous maxim of Eduard Bernstein — that the ultimate goal is nothing and the movement is everything — particularly given that Bernstein and Drahomanov briefly met in Switzerland (Бернштайн 1922: 160).

Lesya Ukrainka, 1896

Lesya’s letters show that she was already familiar with social democracy; in particular, she mentioned the Erfurt Program of German Social Democracy (letter to Drahomanov, July 5, 1893). It is worth noting that the first Russian translation of the Erfurt Program was produced by Kyiv Marxists under the leadership of Bohdan Kistiakovsky and published in Kolomyia by Mykhailo Pavlyk in 1894 (Білоус 2017: 54).

But we should not forget that, unlike social democracy, Drahomanov considered the peasantry to be the main pillar of the socialist movement in the Ukrainian lands. In his letters to Lesya, he praised the political agency of the peasantry, especially in contrast to the passivity of other strata of society: “…at least five hard and industrious souls, until the minds of peasants who, contrary to all examples of history, have more light in their minds than those of Galician academics and professors, will be enlightened. Pavlyk sometimes sent me letters from peasants — Meliton Buchynsky is far behind compared to them” (Драгоманов 1924: 194).

Volodymyr Vasylenko’s illustration for the poem Predawn Lights by Lesya Ukrainka

From her conversations with her uncle, Lesya Ukrainka developed a critical attitude toward the Ukrainian reality of the time, both in the Russian Empire and in Galicia. Moreover, Lesya’s peers tended to idealize the Galician order and were dazzled by the successes of others, particularly the “new era” — the policy of Polish-Ukrainian compromise in the early 1890s.

On her way to Vienna for treatment in 1891, Lesya Ukrainka visited Galicia and witnessed firsthand Galician political life, including preparations for elections and related activities. She was impressed by what she observed and developed a distrust of conservative approaches to political struggle: “The old ‘politics,’ ‘loyalty,’ crooked roads leading to a high ideal, ‘respect for national festivals,’ ‘moderate liberalism,’ ‘national religiosity,’ etc., etc., have already tired us, young Ukrainians, so much that we would be glad to escape that ‘quiet swamp’ for somewhere clean” (letter to Drahomanov, March 17, 1891). In her 1895 article, the Ukrainian poet summarized the “opportunistic and rational” politics of the Galician Narodniks, which she disapproved of, as follows: “…do not fight the sun with a hoe, do not rush, but slowly establish relations with the government and stronger parties” (Українка 2021: 394).

She was also dissatisfied with the atmosphere of the “political” circles in Dnieper Ukraine. First and foremost, the poet was disheartened by the dispersion of these circles and their enforced secrecy, which rendered the results of their work invisible not only to outside observers and the various “pharaohs,” but even to members of other circles: “We do everything in hermetically sealed boxes — you hear some noise, but you don’t know what it is about, and whoever gets into such a box will not feel very good there, because it is still crowded and stuffy, although the box may be good, and the people in it are not worse” (letter to M. Drahomanov, June 25, 1893). In addition, the atmosphere of the circles painfully resembled that of small political sects of our own time, with their intense peer pressure and tendency to loudly “unsubscribe” from the movement over the slightest deviation from the general line. This applied both to the “kulturnyky” circles gathered around Oleksandr Konysky and to the circles of “politicians” (letter to M. Drahomanov, April 5, 1894). Even when the circles later developed into parties, sectarian strife persisted — as did Lesya Ukrainka’s dislike for it (letter to O. Kosach and M. Kryvynyuk, December 6, 1905).

However, Lesya Ukrainka maintained close ties with the members of the “politicians’” circles and with Mykola Kovalevsky, who oversaw them. One speech by Kyiv’s most senior supporter of Drahomanov’s ideas particularly stayed with Lesya Ukrainka: “…he told us that we should start working among the Ukrainian people as soon as possible and persistently, to support and awaken their national self-awareness before it completely fades, because it is already barely flickering. This work had to be legal and illegal, through the means of the printed or spoken word, with the help of all measures, except for deceitful or terrorist ones” (Українка 2021: 416). It was thanks to Kovalevsky, the Galician radical Mykhailo Pavlyk, and her uncle that she joined the movement of supporters of Drahomanov’s socialism, which operated on both sides of the Zbruch River. However, neither Kovalevsky nor Pavlyk could match Drahomanov in terms of their influence on Lesya Ukrainka’s ideology.

Memorial plaque in honor of Mykhailo Drahomanov in Sofia, Bulgaria

Lesya Ukrainka’s political views were most significantly shaped by her year in Bulgaria, from June 1894 to July 1895. There she finally got to know her uncle and his family personally, had unrestricted access to Drahomanov’s huge library, and could freely discuss all topics of interest with Mykhailo Petrovych. The year that Lesya spent with the Drahomanovs in a foreign yet familiar home was compared, with good reason, by a diaspora researcher of Lesya Ukrainka’s work, Petro Odarchenko, to Taras Shevchenko’s “three years” in terms of its impact on the life, work, and views of the writer (Одарченко 1954: 41). She was the sole witness to Mykhailo Drahomanov’s sudden death on June 8, 1895, and even, according to Odarchenko, personally closed her deceased uncle’s eyes. However, the sad end of her stay in Sofia did not diminish the influence of this period on Lesya Ukrainka’s ideas; rather, it emotionally intensified it in some ways and manifested in her devotion to the memory of her relative.

Among the literary works of Lesya Ukrainka’s early period, the most Drahomanian was the poem Robert the Bruce, King of Scots, written in 1893 with a dedication to Mykhailo Drahomanov. This poem serves as a concentrated and most transparent allegorical expression of Lesya’s uncle’s ideas: the betrayal of the national aristocracy (“we have no knighthood, we have no lords”), the attainment of freedom through a peasant rebellion, and delegates from the common people freely threatening the king with disobedience should he deviate from the agreement with them — and he raises no objection. Moreover, the very theme of this poem, and the image of a spider tirelessly spinning its thread after several setbacks and inspiring Robert the Bruce to continue the struggle, were suggested to Lesya Ukrainka by Mykhailo Drahomanov himself (letter to M. Drahomanov, March 15, 1892).

Robert the Bruce, King of Scots. Woodcut by Volodymyr Vasylenko

Mykhailo Drai-Khmara noted that it was Olena Pchilka, the poet’s mother, and Mykhailo Drahomanov who were the decisive influences in shaping Lesya’s personality: “While her mother employed all means to make her a Ukrainian writer, her uncle made sure she became a human being and a fighter” (Драй-Хмара 1924: 34).

However, nothing could be more misguided than reducing Lesya Ukrainka to a mere conduit for her great uncle’s ideas. First, such a notion smacks of sexism. Second, it is simply untrue. Mykola Zerov, a Neoclassicist like Drai-Khmara, rightly distinguished two broad types of Ukrainian followers of Drahomanov and placed Lesya Ukrainka in the second category: “Some, like Pavlyk, remained entirely captive to his [Drahomanov’s — M.L.] vivid individuality, never forging their own paths. If they differed from one another, it was only in temperament and in the extent of their devotion to the Drahomanov cult. Others, like Franko, absorbed only the essence of his doctrine but cultivated it in their own way, shaped by other influences, and ultimately bore fruit that was distinctly their own, entering history with a unique and sometimes sharply defined identity” (Зеров 1990: 363). This assessment may be unfair to Pavlyk, but it is entirely accurate when it comes to Lesya Ukrainka, whose reverence for her distinguished relative never constrained her own intellectual evolution — indeed, Drahomanov himself would have been dismayed had it been otherwise.

Thanks to Drahomanov’s influence, Lesya Ukrainka strengthened her critical attitude toward conservative and narrowly nationalist politics without rejecting national identity. It was not without her efforts that her Ukrainian literary circle abandoned the label of “Ukrainophiles” and began calling themselves simply Ukrainians. At the same time, Lesya was deeply drawn to the ethical dimension of Hromada socialism, with its rejection of the same “cunning and terrorist methods” and all forms of opportunism — true to Drahomanov’s conviction that “a pure cause requires clean hands.” His heterodox brand of socialism provided fertile ground for exploring and assimilating new socio-political ideas, and Marxism was inevitably part of that equation.

National Social Democracy

Lesya Ukrainka’s relationship with Social Democracy and Marxism is a subject rich in myth-making potential. It is well known that, together with Ivan Steshenko, she was a founder and ideological driving force behind the so-called “USD group,” the first Ukrainian Social Democratic association within the Russian Empire. She identified herself as a Social Democrat, as attested by her friend Liudmyla Starytska-Cherniakhivska in a conversation with Mykhailo Drai-Khmara (Драй-Хмара 1924: 35).

There is also a widely held belief in leftist circles that Lesya Ukrainka was the author of the first Ukrainian translation of The Communist Manifesto, published anonymously in Lviv in 1902. In a letter to Ivan Franko dated September 7, 1901, Lesya expressed her interest in the publication of several socialist texts in Galicia, including The Manifesto and her translation of Szymon Dikstein’s brochure Who Lives Off What (letter to Ivan Franko, September 7, 1901).

“Conscious of their class, workers must stand together unanimously, because they all have the same enemy — the class of the rich, capitalists who profit from labor.” From Lesya Ukrainka’s afterword to her translation of Szymon Dikstein’s brochure Who Lives Off What. Photo: Brian Oswald

The Ukrainian translation of The Manifesto appeared in Lviv in 1902 under the imprint of the “Publication of the Ukrainian Socialist Party” — a label that the USD group never used. Moreover, the translation itself is rather careless, full of Russicisms and Polonisms; for instance, the translator refers to the week as “nedilia,” a usage Lesya herself never employed, as she was extremely meticulous about language in her own writings. Meanwhile, between 1900 and 1904, a small Ukrainian Socialist Party (USP) led by Bohdan Yaroshevsky existed in Dnieper Ukraine, primarily on the Right Bank. This provides grounds to suggest that the author of the 1902 translation of The Manifesto was, in fact, Bohdan Yaroshevsky (Жук 1957: 228).

The preface to this translation was published only once — in a Russian edition of Lesya Ukrainka’s works in 1957 — and not from an autograph manuscript. None of this rules out the possibility that Lesya may have translated The Manifesto and made efforts to have it published, but the version that appeared in Lviv in 1902 was not hers. Until we have the manuscript of her translation in hand, there is no reason to assume otherwise.

Cover of the 1902 Ukrainian edition of The Communist Manifesto

By the late 1890s, Lesya Ukrainka had become deeply interested in social democracy and its theories. In 1897, she studied Capital but was disappointed with it, noting that she did not find the “strict system” she had been told so much about (letter to O. Kosach, September 11, 1897). However, this does not undermine her commitment to social democracy — many socialists struggled with Capital, and no one was expelled from the movement on that account. She also studied the materialist conception of history in Marx’s interpretation and its application to Ukrainian material, arriving at conclusions about the importance of class antagonism in Ukrainian history: “[I] can express my view of the history of Ukraine under Moscow’s rule with the following Marxian periphrasis: ‘We perished not only because of class antagonism, but also due to the lack thereof’” (letter to M. Kryvynyuk, November 26, 1902).

In her letters to the staunch Drahomanovite Mykhailo Pavlyk, Lesya emphasized that social democracy was “too universal a movement for the Ukrainian nation to do without” (letter to M. Pavlyk, June 7, 1899). She also saw nothing wrong with the fact that a social democratic faction had left the ranks of the radical party and formed its own party; on the contrary, she welcomed it, although she had many complaints about the Galician social democrats (letter to M. Pavlyk, March 2, 1899).

It is worth noting that shortly before this, in 1896–1897, a revealing debate took place between Lesya Ukrainka and Ivan Franko. In his article “With the End of the Year,” which initiated the controversy, Kamenyar (Franko’s pen name, meaning “mason” in Ukrainian) adopted a condescending tone toward the Drahomanovites from Dnieper Ukraine (whom he referred to as “Ukrainian” in his terminology) and dismissed their experience of struggle — an attitude Lesya Ukrainka challenged in her response. Franko complained that Ukrainian radicals were afraid of engaging in illegal activities and acted “only with the permission of the authorities.” He held up Galician radicals as a counterexample, praising their willingness to defy the “stepmother constitution” and work directly with the peasantry — something he claimed their counterparts in Dnieper Ukraine lacked the resolve to do. Ultimately, Franko disparaged the activities of the Ukrainian leftist intelligentsia as “a kind of tincture of radical ideas, not real radicalism.”

Postcard sent by Lesya Ukrainka from Câmpulung to Ivan Franko on May 29 [O.S. June 11], 1901

Ultimately, what outraged her most was the accusation that Ukrainian radicals were allegedly doing nothing and were afraid of engaging in illegal activities. In 1896–1897, “some of those comrades ended up in ‘free accommodations’ — with the permission of the authorities.” She was referring to Mykhailo Kryvynyuk and Ivan Steshenko, who were imprisoned during that period for their participation in the student movement. Nevertheless, this controversy did not significantly affect her personal relationship with Ivan Franko: Lesya Ukrainka was able to distinguish between the personal and the political, between “friends of my friends” and “friends of my ideas,” as she herself put it (letter to Ivan Franko, August 14, 1903).

These events took place in the early years of the Ukrainian Social Democracy group mentioned above. The group operated in secret and was never exposed during its existence, so little evidence remains about the size of its membership. Its core members definitely included Ivan Steshenko, Lesya Ukrainka, Mykhailo Kryvynyuk, and Lesya’s sister, Olha Kosach, but the participation of other individuals often listed as members remains highly doubtful (Лавріненко 1971).

The exact date of the emergence of the USD group remains unknown. Researchers and contemporaries have proposed different years — ranging from 1893 to 1897 (Феденко 1959: 19; Тулуб 1929: 98). Most likely, the group was established sometime in 1896, with the initiative coming from Ivan Steshenko — who would later become a member of the General Secretariat of the Central Rada and was, at the time, a student at the Faculty of History and Philology at Kyiv University. It was Steshenko whom Oleksandr Morhun recalled as the leader of the “radical group” within the Ukrainian student community in Kyiv in the mid-1890s: “The radical group, led by Steshenko, began to challenge the community’s apolitical stance and its indifference to social issues, seeking to give the community a more defined character in this regard” (Моргун 1963: 427–428). Steshenko was opposed by the group led by Mykola Mikhnovsky, who believed that such issues should not be raised. Therefore, the claim about the influence of the Taras Brotherhood’s ideas on the USD group (Головченко 1996: 12) appears rather questionable.

Ivan Trush, Portrait of Lesya Ukrainka, 1900

By 1896, two other social-democratic groups already existed in Kyiv, known in underground circles at the time as the “Polish S.D. group” and the “Russian S.D. group.” However, the core of the first group consisted of Lithuanian students at Kyiv University, while the second had been founded by Bohdan Kistiakovsky and included active participation from Jewish and Ukrainian students of the same university, including former “Drahomanovite” Pavlo Tuchapskyi. These two groups, along with another that had previously been affiliated with the Polish Socialist Party, joined forces in 1897 to form the Kyiv “Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class,” which, in 1898, contributed to the establishment of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; Білоус 2017: 53). Among those involved in preparing the party’s First Congress was a member of the Union, the Belarusian Marxist Serhiy Merzhynskyi, with whom Lesya Ukrainka maintained a close relationship.

Given this context, it seems reasonable to assume that the USD group represented an attempt to establish a third Kyiv-based social-democratic organization and to prevent the outflow of Ukrainian youth into all-Russian movements. Unlike the other groups, the USD did not join the “Union of Struggle” or the RSDLP. Its members continued to operate independently and focused more on other Ukrainian socialist parties — such as the Galician USDP (Ukrainian Social Democratic Party), the aforementioned Ukrainian Socialist Party (USP), which consisted of Ukrainians of Polish culture, and the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP), among whose four co-founders were two sons of prominent “kulturnyky” (cultural activists) of the Old Hromada: Dmytro Antonovych and Mykhailo Rusov.

Lesya Ukrainka. Sanremo, 1902

Lesya Ukrainka wrote a critique of the “Outline of the Program of the Ukrainian Socialist Party,” and her letters to Mykhailo Kryvynyuk show that she closely followed the evolution and internal struggles within the RUP. She specifically criticized the RUP newspaper Haslo for adopting, as its slogan, the aforementioned phrase by Eduard Bernstein: “The ultimate goal is nothing; the movement is everything.” This suggests her position within the broader contemporary debate in the international socialist movement between the reformist wing, represented by Bernstein, and the revolutionary wing. Lesya Ukrainka noted that “the editorial board completely misunderstood Bernstein’s anti-revolutionary stance,” and later added that she “liked the article in Volia [the official paper of the Galician USDP — Ed.] against the Bernsteinianism of Haslo” (letters to M. Kryvynyuk, March 14, 1902, and April 22, 1902). However, as will become clear later, her views also diverged significantly from those of many leftist critics of Bernstein.

Lesya Ukrainka’s letters also shed light on how the USD group came to an end. In December 1905, she wrote to her sister Olha and Mykhailo Kryvynyuk about the USD’s negotiations with the RUP. The latter was renamed the Ukrainian Social Democratic Labor Party (USDRP) at its congress and formally adopted social-democratic and federalist positions. However, since the USDRP did not allow autonomous groups within its structure, the USD did not join the party as a collective entity. Only a few members of the USD — Lesya Ukrainka among them — agreed to participate independently in the publication of the new social-democratic newspaper Pratsia (letter to O. Kosach and M. Kryvynyuk, December 6, 1905).

Unfortunately, for various reasons, the newspaper was never published. One of these was the arrest of Petro Dyatlov, who had been designated as its editor. It was a quote from his obituary for Lesya Ukrainka — later inscribed on her tombstone — that recently sparked outrage among the “patriotic public.”

“Lesya Ukrainka, standing close to the liberation movement in general and the proletarian movement in particular, gave all her energies to it, sowing the sensible, the good, and the eternal.” Inscription on Lesya Ukrainka’s tombstone. Photo: Sarapulov, Wikimedia Commons

Revolutionary Ethics and the Spirit of Socialism

Ideologically, the USD group emerged at the intersection of Marxist influence and Drahomanov’s brand of socialism. Its early publications already reflected both a critical stance toward Drahomanov and a search for alternatives. One of the group’s first publications was the anonymous pamphlet Mykhailo Petrovych Drahomanov (Ukrainian Emigrant), published in 1897. It acknowledged Drahomanov’s significant contributions to the Ukrainian movement — particularly his call for the creation of independent Ukrainian socialist organizations. At the same time, it also offered a Marxist critique of his socio-political views.

The author of the pamphlet — whoever it was — points to the peasant character of Drahomanov’s socialism and argues that, with the advance of capitalism, the peasantry is gradually losing its social homogeneity — if it ever possessed any at all. The pamphlet contends that framing the issue in terms of “the peasantry in general” is vague and unproductive: “…to grieve for the fate of the peasantry in general means not to say anything clear; the modern class principle of sociology demands that one precisely indicate the interests of which class of farmers the patriot wishes to defend, because only under such conditions can his sympathy for the farmers have any real significance” (quoted in Феденко 1959: 19).

Lesya Ukrainka also recognized the need for different approaches in different circumstances. While in the countryside the assimilation of Ukrainians progressed slowly and the Social Democrats could focus on strictly socialist propaganda, among urban workers it was also necessary to promote national consciousness — “so that they do not become strangers in their native land and set against their own brothers.” In other words, to prevent a widening of the cultural gap between city and countryside in Ukraine (Українка 2021: 504). In the afterword to the brochure Who Lives Off What, Lesya conveys the ideas of class struggle, internationalism, and workers’ self-organization in the most accessible way possible. She presents an ideal of grassroots workers’ self-organization — from the local to the international level — that closely resembles Drahomanov’s vision of a “free union.” Similarly, she acknowledged different methods of struggle for workers’ rights: “whether by request, or by threat (more by threat than by request), or by conspiracy, or by weapon” (Українка 2021: 432–433).

Davyd Chychkan. Hryvnia of an Alternative Ukraine

Above all, the influence of Drahomanov’s socialism endured in Lesya Ukrainka’s ideas about the ethics of political struggle. This is especially evident in her response to the article “Politics and Ethics” by Mykola Hankevych, leader of the Galician USDP. Lesya rejected the dualistic view of “either opportunism or fanaticism,” insisting that no party or individual thinker can claim absolute truth. She sought to transcend this binary, and it was Drahomanov’s ideas that guided her: “Fortunately, there is still the road of firm belief based on criticism and a burning, voracious thirst for further truth” (Українка 2021: 456). At the same time, she continued to uphold her uncle’s principle that “a pure cause requires clean hands,” and did not view politics as inherently dirty. For her, it was not politics that corrupted people, but people who corrupted politics.

Lesya Ukrainka’s aversion to fanaticism and claims to absolute truth led to her disapproval of terror. She regarded revolution with equanimity and believed that mass movements could serve both progressive and reactionary causes — citing, for example, the French Revolution and the Vendée insurrection. While she did not equate the two, she considered the suppression of the French Revolution worse than the suppression of the Vendée revolt, and acknowledged that human progress unfolds unevenly and does not preclude intense periods of revolution (Українка 2021: 480). However, she believed that terror was fetishized by its supporters — both revolutionaries and reactionaries — from the “crimson-fingered Sanson”[1] to Muravyov the Hangman[2]. “And when it comes to judging the ethics of an executioner, it’s his executions that should be judged, not his monarchism, republicanism, aristocracism, bourgeoisness, etc.” (Українка 2021: 483). Lesya Ukrainka would not have aligned with Lev Trotsky and his Terrorism and Communism, just as she would have rejected Dontsov’s immoralism.

Cover of a standalone edition of Lesya Ukrainka’s 1901 translation of the brochure Who Lives Off What? (1881) by Szymon Dikstein

She described terror as a degenerate form of revolution and opposed it on universalist ethical grounds. At the same time, Lesya Ukrainka was neither a pacifist nor a supporter of nonviolent resistance. In an unfinished draft of her essay on the state system, she justifies the use of force to defend freedom against aggressors and does not consider such defense a violation of anyone’s freedom (Українка 2021: 427). The moral equivalence of victim and executioner, of aggressor and the attacked, was entirely foreign to her.

Cosmopolitan in Ideas, National in Roots

Speaking of Drahomanov’s federalism and the question of independence, Lesya Ukrainka’s views on the relationship between Ukrainian and Russian socialists differed sharply from the stereotypical image of the Ukrainian left as Russophilic — an image that, unfortunately, some still readily embrace. First and foremost, she, like all committed socialists, held a fiercely negative view of Russian Tsarist autocracy and its repressive policies. This attitude is vividly expressed in her poem The Voice of a Russian Prisoner: “Yes, Russia is huge — hunger, illiteracy, criminality, hypocrisy, endless tyranny, and all these great misfortunes are huge, colossal, grandiose” (Українка 2021: 402). That is why she might not have approved, but certainly understood the motivation of Ukrainian revolutionaries who joined all-Russian organizations to fight the Tsarist autocracy. They were driven both by a desire to resist imperialism and by frustration with the lack of active resistance within the Ukrainian movement.

Lesya Ukrainka among Ukrainian writers gathered in Poltava for the unveiling of a monument to Ivan Kotliarevsky, 1903

In the afterword to Dikstein’s brochure, Lesya Ukrainka used the slogan “Workers of the world, unite!” However, she refined it: “Unite, as the free with the free, as the equal with the equal!” She also added, in another part of the brochure, the following words: “…without transforming into a foreign system, and without being hostile to the workers of other nations” (Українка 2021: 433–434). The national question in social democracy interested Lesya perhaps most of all, and in one of her letters to Pavlyk, she even expressed a desire to write a detailed essay on the subject, in which she would pay particular attention to the relationships between Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, and other social democratic organizations (letter to M. Pavlyk, June 7, 1899). In her assessment of the “Outline of the UPS Program,” she pointed to the potential format of such relations, which envisioned a federal principle for organizing a nationwide party: “It seems to us that such a union would hardly help our cause, and we would rather naturally desire some separation, that is, a division into factions, more corresponding to the national divisions of the Russian state” (Українка 2021: 500).

Lesya Ukrainka emphasized the distinctiveness of the Ukrainian organization from the Russian one and all others, insisting that the alliance of social democrats in the struggle to overthrow autocracy must be strictly equal, without the dominance of one faction over the others. Commenting on the initiative of the Galician newspaper Zoria to reconcile the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks, she wrote: “It is time to adopt the standpoint that ‘brotherly nations’ are simply neighbors, bound, indeed, by the same yoke, but in essence, they do not have identical interests. Therefore, it is better for them to act at least side by side, but each on their own, without interfering in the internal politics of their neighbor” (letter to M. Kryvynyuk, March 3, 1903). Moreover, Lesya rejected the idea of unconditional cooperation with the Russian revolutionary movement. She believed that for such cooperation to be possible, Russian revolutionaries had to recognize the national and cultural distinctiveness of Ukrainians and take it into account. Until that happened, she considered it beneath her dignity to ingratiate herself with the Russians as a comrade. At the same time, when representatives of the Russian revolutionary émigré community asked for her help with translations, she agreed — but only on the condition that she remain an independent translator (same letter).

Lesya Ukrainka with her relatives, Zelenyi Hai, summer 1906

To conclude the topic of nationality, Lesya Ukrainka was well aware of the idea of independence but did not consider it an end in itself. In the near term, she deemed it most appropriate to support a federalist program, at least during the ongoing struggle against the Tsarist autocracy, which, in her view, should take place within the framework of the entire empire in cooperation with socialists from other nations. However, if the "brotherly union" were to prove itself not so brotherly — that is, if the right of the Ukrainian people to free development were not upheld within the new federation — Lesya Ukrainka did not oppose full state separation (Українка 2021: 502).

***

Lesya Ukrainka’s political views were shaped under the strong influence of her uncle, Mykhailo Drahomanov, from whom she learned, above all, a critical perspective on Ukrainian reality, an understanding of the importance of political activity, and the ability to find a balance between national and universal (“cosmopolitan”) values. Concepts such as attention to the ethical component of political struggle, which was at the core of Drahomanov’s socialism, a worldview rooted in Europeanism, and disdain for national isolationism remained central to Lesya Ukrainka’s literary and political endeavors throughout her life.

Yet even during her uncle’s lifetime, Lesya Ukrainka immersed herself in various currents of socio-political thought, among which Marxism held a prominent place. While calling her a thoroughgoing Marxist would be an overstatement, she undoubtedly absorbed the significance of the class-based approach to understanding societal phenomena from Marxism and applied it to the Ukrainian context — from analyses of contemporary politics to questions of history and literature. Her Marxism, however, was neither dogmatic nor purely reformist; she approached revolution with calm discernment, free from fanaticism or fear.

Olena Kulchytska. Lesya Ukrainka. Poster, 1920

Of course, the influences shaping Lesya Ukrainka’s worldview extended beyond Drahomanov and Marx alone. In her article “Utopia in Fiction,” traces of Friedrich Nietzsche and Georges Sorel’s concept of the revolutionary myth are distinctly evident. Yet this only underscores Lesya’s intellectual integrity, her comprehensive development, and her critical acumen, as both Marxism and Drahomanov’s ideas, in their essence, champion such qualities over uncritical adulation or dogmatism.

At its core, Lesya Ukrainka’s political philosophy was rooted in Drahomanov’s ideals, yet it harmoniously blended Marxism with Hromada socialism and Ukrainian national aspirations. Her perspective demonstrates, first, that Marxism and Drahomanov’s thought could coexist, and second, that Ukrainian social democracy in the early 20th century was neither a mere offshoot of Russian models nor incapable of meaningfully addressing the national question.

Today, some authors downplay the Ukrainian intelligentsia’s enthusiasm for socialism during that era, portraying it as a fleeting trend, a phase of youthful rebellion, or a sign of the supposed naivety and inexperience of both these figures and the Ukrainian movement as a whole. For Lesya Ukrainka, however, socialist ideals were a cornerstone of world culture — a framework through which Ukrainian realities could be understood and transformed for the better. Unlike many modern commentators, she did not pit national identity against socialism — whether Drahomanov’s version or the broader social-democratic tradition. To oppose these two ideals so dear to Lesya, and to promote one while silencing the other, is to turn away from the predawn lights lit by Lesya Ukrainka and her like-minded contemporaries, who aspired to both social and national liberation.

Footnotes

- ^ Charles-Henri Sanson was a Parisian executioner under King Louis XVI and the French Revolution who carried out nearly 3,000 executions (including by guillotine); he is called “crimson-fingered” in the dialogue between a montagnard and a girondist in Lesya Ukrainka’s Three Minutes. — Ed.

- ^ Mikhail Muravyov-Vilensky, the “Hangman,” was a Russian governor general responsible for the brutal putting down of the 1863–1864 uprisings in Poland, Belarus, Lithuania, and Volhynia. — Ed.