On 10 March this year, students of the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture (NAOMA) went on a picket to demand that repairs to their dormitory be started and that communal services prices be reduced. The protest was the culmination of events that began in November last year, when, in the midst of the first cold weather, residents who had neither water nor heating running in their radiators received monthly housing bills of around UAH 1300. Activists of the Independent Student Union Direct Action (Priama Diia) paid attention to these problems and joined the fight for decent living conditions.

It is not the first time in the modern history of the academy that NAOMA students have fought against the bureaucracy of their university. The latter does not hide its paternalistic, conservative attitude towards students and does not hesitate to use various instruments of pressure to maintain the status quo. Since at least 2016, the Academy of Fine Arts has been not only a place where knowledge was literally produced, but also a space of vivid social conflict, which in higher education is masked by the depoliticisation and alienation of universities. And this conflict is worth chronicling and analysing as an example of inconsistent public policy, as well as a source of experience that allows us to draw conclusions and move on, opening up new areas where decommercialisation and the introduction of libertarian pedagogy in higher education will be on the agenda.

The history of the student struggle at the NAOMA, local bureaucracy, stupid state policy in the field of education and lessons to be learnt will be described further in the text.

Supporting changes, opposing censorship, supporting elections, supporting warmth: student protests at the Academy in 2016-2023

To begin with, we need to talk about the Academy of Fine Arts in general. The Academy is a small Kyiv-based university controlled by the Ministry of Culture and Strategic Communications. As of November 2024, it had about 1,200 students, the vast majority of whom were women. The academy is located in the old building of a former theological seminary, a building that is a national monument. During Soviet times, an additional building was built. Most of the facilities at NAOMA are used for workshops, where the training takes place. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, the educational process here remained mostly offline, with only non-specialised and theoretical subjects being taught remotely. Students are assessed on the basis of their final projects, which they present at the end of the semester during reviews. At that time, open days are held: the walls of the NAOMA, its hallways and rooms are covered with works; master classes are held.

In other words, the National Academy of Fine Arts is a network of workshops where students (mostly on their own) produce original works that, in the eyes of lecturers and collectors, turn into commodities and gain exchange value. However, due to the specifics of art academies, this process of alienation and commodification is constantly met with resistance from students. Here, the distinction between physical and intellectual labour is blurred, as students literally produce works with their own hands; moreover, students often purchase the necessary materials and tools at their own expense, which also affects their involvement in production. As students work on their projects at a university, both their working conditions and the quality of their education determine the quality of the final product, in which they invest a lot of time and emotion. Indeed, this is true to some extent for all higher education institutions. However, it is here that the precarity of student labour and the crisis of the university take on a concrete, material and spatial form.

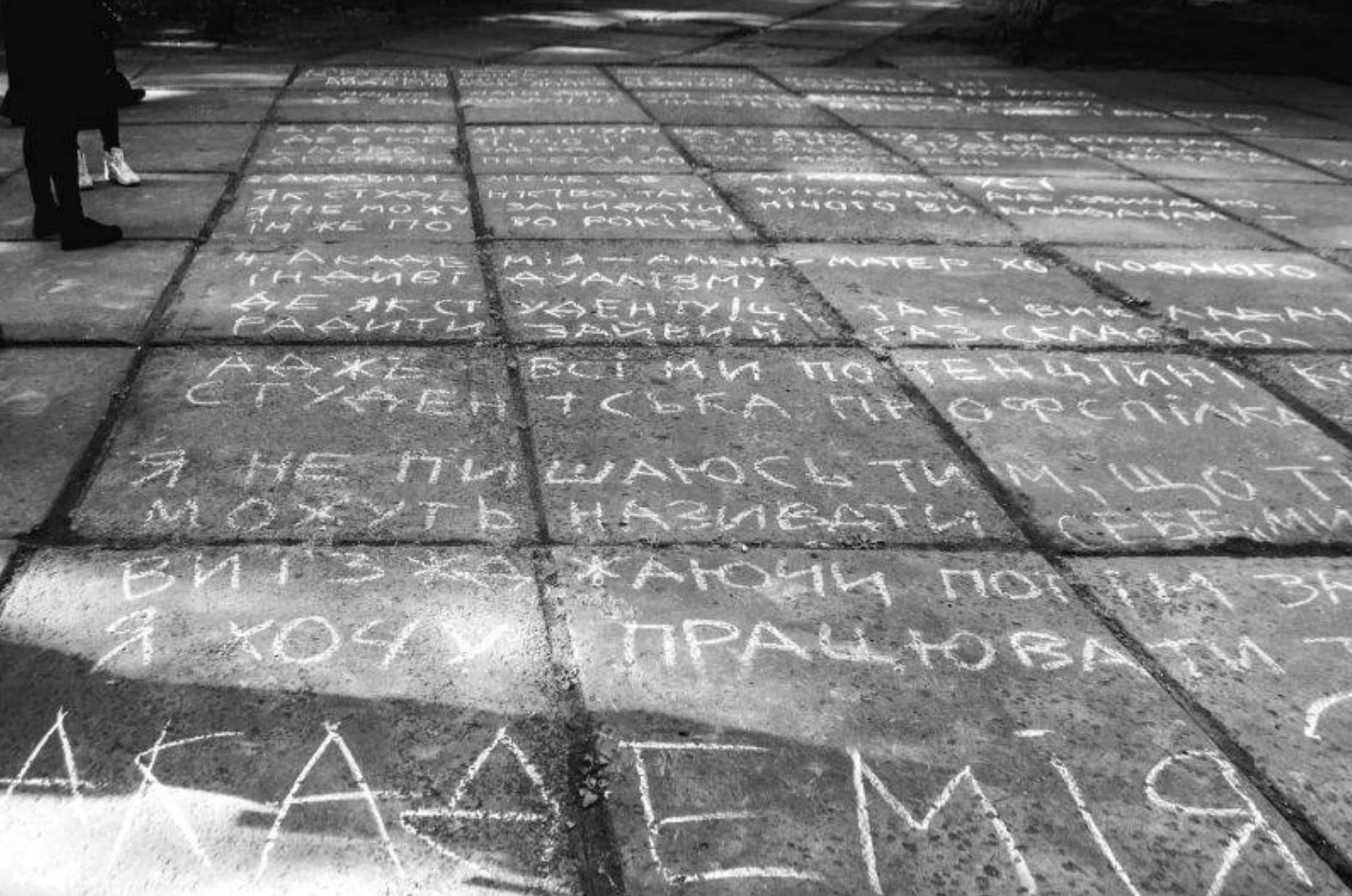

The National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture has a vivid protest history. In 2016, fourth-year student Aliona Mamai organised a performance called Action at the Door in front of the main entrance of the Academy. She wrote a manifesto on the road plates and handed out brochures that addressed a number of problems regarding the academic process: non-public viewings and evaluation of works without the students' participation; a minimum number of classes, which are often unattended by the lecturers; and education that does not prepare students for the realities of the art market. At that time the administration reacted negatively: security guards tried to interfere with Mamai and called the police; the then rector, commenting on the situation, accused that there was some group of people who were ‘undermining the powerful school.’ There is little information about these events in the public domain, but there are mentions that after the protest, students and lecturers established a department of contemporary art and launched the self-publishing house Vono dedicated to the life of the academy.

“Action at the Door” by Aliona Mamai. Photo: Sofia Berginer

In year 2019, Spartak Khachanov, a student of the National Academy of Fine Arts (he has a controversial reputation among students: in particular, while studying at the National Academy of Fine Arts, he created a conceptual embroidery made of salo, which he later threw into the trash. Added on 27.03.2025) created an anti-war installation of small tanks, military figures and phallic missiles, which was nicknamed the ‘parade of dicks’ in the media. The exhibition provoked the outrage of one of the lecturers, who eventually destroyed the installation. Later on, Khachanov was put under pressure: he was summoned to the Academic Council, where he was threatened with dismissal, and after this conversation, the artist was met on the street by far-right activists from the C14 organisation. The situation received media coverage, and students organised two protests in support of Khachanov with the slogans ‘No to censorship in NAOMA’ and ‘Totalitarianism is a way of thinking’, during which they collected signatures against his dismissal. Eventually, the administration decided to leave the author of the installation alone.

Action in support of Spartak Khachanov. Photo: Evgeniy Maloletka

In December 2020, NAOMA was due to hold rectorial elections in accordance with the new educational legislation, however, at the last minute, the Ministry of Culture postponed them indefinitely and appointed one of the candidates, Ostap Kovalchuk, as an acting head of the Academy. In response, the students organised several protests demanding the resumption of the election process and created a monitoring NGO, Pro NAOMA. This action was also supported by the academy's faculty, and the Academic Council expressed a vote of no confidence in Kovalchuk. Eventually, elections were held, and Oleksandr Tsuhorka became the rector.

The students of the Academy had raised housing issues before this year's events as well. In 2021, the NAOMA was at the centre of a public scandal after the administration banned life drawing classes, explaining that it was cold in the classrooms. In November 2023, when there was no heating in the NAOMA buildings, students went on a picket. Then the rector solemnly turned on the faucet, and the heat came on.

In addition, in December 2023, the residents of the dormitory collectively appealed to the administration to cancel the additional fee for communal services, which in November exceeded UAH 1,200 per month. In their statement, they noted that such an additional charge, along with the bed fee of UAH 800, was illegal: according to the government regulations and orders, the dormitory fee already includes the utility costs. Moreover, the maximum amount of payment for accommodation in dormitories of educational institutions for students cannot exceed 40% of the academic scholarship. The collective statement was sent to the administration, and the next day the vice-rector for household services came to the dormitory. According to the students, he pressured the signatories: he gathered the dormitory supervisors and threatened that if such initiatives were repeated, the administration would transfer the cost of the utility bill as an additional fee for the use of electrical appliances, and they would have to pay even more. However, the students' resistance paid off and the utility bills for November were allowed to be waived.

Neither Vono nor Pro NAOMA are functioning anymore. The NAOMA never formed a permanent organisation that would accumulate and pass on the experience of student struggle. There are few public records of these events, and alumni rarely shared their memories, which is why the achievements and successes of previous generations remained unknown to new students.

However, while in other universities local student unions and student councils usually play the role of a ‘junior partner’ of the administration, providing support to its authorities, at NAOMA they are militant independent organisations that bring together people ready for open conflict. A similar situation, at least seemingly, can be observed in another creative higher education institution, the Kyiv National Karpenko-Kary Theatre, Film and Television University. There, during the scandal surrounding Andriy Bilous, the local student council supported the victims and initiated a meeting at which, after a lengthy discussion, the administration agreed to suspend the lecturer. As a result, a joint working group with students was set up to address the problems at the university.

Participants of the action in front of the Molodyy Theater. Photo: Dasha Hryshyna

Paternalism and patriarchy at NAOMA: how Direct Action (Priama Diia) went to the negotiations

Student activism at NAOMA is based not only on the specifics of studying at the Academy, but also on the antagonism with which the administration meets student initiatives. The administration does not see students as equal subjects and uses paternalistic and patriarchal practices in managing the university. If David Graeber's famous statement is relevant to any academy, then it's about NAOMA:

“In fact, the modern university system is about the only institution – other than the British monarchy and Catholic Church – to have survived more or less intact from the High Middle Ages. What would it actually mean to act like an anarchist in an environment full of deans and provosts and people wearing funny robes, conference hopping in luxurious hotels […]. At the very least it would mean challenging the university structure in some way.”

I would like to provide a few examples that clearly demonstrate the dominant discourse in this institution. On December 13, 2024, Mykhailo, another Direct Action (Priama Diia) activist, and I, along with the dormitory residents, came to the rector's office in order to find out where the office of Volodymyr Bondarchuk, the acting vice-rector for educational, production, financial and administrative activities, was located. Tamara Kasyanenko, the acting first vice-rector, immediately took us to her office, called Bondarchuk, who started explaining why the dormitory had cold radiators and high utility prices. During the conversation, Bondarchuk repeated himself about ten times: ‘You are our children, we will take care of you’. Kasyanenko, on the other hand, said that we must realise that there is a war in the country, so students must be united and suffer a little. In addition, the administration accused the students of excessive use of electrical appliances, which, according to them, caused a lack of electricity in the dormitory.

Windows in the NAOMA dormitory

We then agreed to have another meeting on Monday, to which we were to bring a list of dorm rooms with problematic windows and radiators. On December 16, I went to the acting vice-rector with five other dormitory residents. When we handed over the above list, Kasyanenko refused to answer the question about the timing of the repairs. After that, one of the students was outraged and began to complain that these problems had been going on for years, and the administration did nothing but promise. The first vice-rector, in the best traditions of the dominant monolingual discourse, rebuked the student: ‘Why are you speaking the language of the occupier during the war? Do you realise how disrespectful this is to the soldiers?’ When the same complaints were made again, this time in the official language, Kasyanenko began to make excuses that she had only been in office for six months and the academy had little money. In the end, we agreed verbally that we would be given a response to the appeal and the timing of the repairs by around the 20th of December. The 20th passed, but there was no response.

On December 30, other members of the Direct Action (Priama Diia) union and I, along with one of the dormitory residents, came to find out about the administration's response. It was a very conflicting day: they didn't want to let us in, the local acting dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts and Restoration, Ihor Melnychuk, checked our documents and threatened to call my university. We were convinced that the Academy was closed for the holidays and no one was there, although there was an announcement of an open exhibition on the official resources of the National Academy of Fine Arts. In the end, we were allowed to enter the rectorate, where we were met by an angry Kasyanenko with a piece of paper in her hand. She said that ‘only Remizovskyi’ would be acquainted with the response, since the application was made on my behalf. So I went with her. I was led into some cramped office, the acting dean, the acting vice-rector and the dormitory superintendent sat comfortably in armchairs, while I was given a wooden chair.

“Please, have a seat,” Melnychuk said.

“Thank you, I'll stand,” I replied, as I didn't plan to stay long, especially since I was brought in as if to simply get an answer.

“No, no, have a seat.”

“No, thank you very much, I feel more comfortable this way.”

“If you want to talk,” the dean's voice became very cold, "have a seat."

I took a seat. The administration's undisguised desire to make me feel like a “bad student” in the school principal's office seemed so absurd that I had the urge to laugh right there. For about 40 minutes, Kasyanenko read aloud to me a memo in which the administration claimed that all the problems had already been solved, and accused me of all kinds of things – from “building a career as a student leader” to allegedly “personal interest” in female students. For some reason, the bureaucrats decided that I was the main person in this process and tried to put pressure on me to get consent to relocate students living in unsatisfactory conditions. I replied that such issues should be resolved directly with the residents, and then suggested organizing a meeting in the dormitory. The first vice-rector responded sharply: “Don't you dare put conditions on us.” Finally, the conversation ended in nothing, and we went out into the corridor.

Mold in the NAOMA dormitory

In February, when the students returned from vacation to a cold dormitory, administration, aware of the students' discontent, organized a meeting. We were not allowed to attend, although the students insisted on the presence of representatives of our union. Melnychuk responded to their arguments with a stern fatherly tone: "We have our own lawyers. They will advise you. Don't you trust the administration of the academy?" It should be noted that he received a unanimous negative response. But the main thing in this story is that the dean raised such a question at all, and he did it in such a way as if distrust of the academy's administration was some kind of crime.

This resembles Sigmund Bauman's discussion of specialized bureaucracy, where objects (in our case, students) remain under the control of a specific bureaucratic structure whose influence cannot be avoided. The bureaucracy does its best to give its “target audience” the impression that “any appeals to centers of power outside the bureaucracy in charge are vain or ineffective.” Sometimes, bureaucrats define such attempts as violations of informal rules that they themselves have established, and begin to “punish” by abusing their powers[1]. This creates an atmosphere of fear designed to make students think that it is easier to obey bureaucratic rules than to fight for their rights.

Such an administrative paternalism is rather a tradition for the NAOMA. Andrii Chebykin, Tsygorka's predecessor, who led the academy for… thirty-two years in a row, used similar rhetoric. Here, the administration considers the Academy as an extension of its own “body,” which is constantly threatened from the outside and which it has “grown” on its own. In the eyes of the administration, students are not workers who work alongside the administration in the workshops, but rather chickens that they raise in incubators. At the same time, they can also be charged for various services, the demand for which is arbitrarily and artificially created by the administration.

So, until February 2022, the dormitory had a free laundry service as the residents purchased washing machines themselves and let everyone use them. However, it was in February 2022 that the administration banned the use of personal washing machines and forced them to be removed, leaving the only ones available for rent from the company Postiraika. In September of the same year, an additional fee for utilities was introduced, with residents paying for electricity according to the industrial tariff, which is 1.5 times higher than the standard tariff for consumers. In October 2022, the gas boiler room connected to the central supply was dismantled and replaced with a less powerful electric boiler, which made the building less efficiently heated forcing residents to heat with their own appliances. The thirst for maximizing profits has also resulted in the canteen ceasing to function at the university in the second semester of 2024, in part because the rector doubled the rent for the contractor. And in 2025, students saw a draft of additional services, according to which they were going to be charged for using refrigerators, which they had, in most cases, purchased themselves.

In this context, the National Academy is a vivid example of how control and commercialization go hand in hand, with the university, using a command-and-control model of management, becoming a miniature state capitalism. If the administration were really interested in replacing, say, the old wooden windows in the dormitory, which it says cannot be quickly updated due to lack of funding and bureaucratic obstacles, it could at least lower the price per bed, so that the price would cover only the necessary costs of dormitory staff. This would allow the residents to invest the savings in repairs. The Academy's management could also publicly appeal to the Ministry of Culture and, together with the students, seek to increase funding and simplify bureaucratic procedures. However, such steps would jeopardize the profits that the administration makes from its legal and infrastructural monopoly. This also undermines the validity of its claim to absolute power in the university: is there a reason for it to exist if students themselves solve the problems of the Academy? Playing with Althusser: the need to think and justify their position of power is what gives rise to rhetoric from the administration such as: “You are our children”, “The enemies want to destroy the school”.

Fallen plaster in the NAOMA dormitory

And what about the state? Same as always: “No authority.”

Local commercialization in universities would not be so widespread if it were not for the general policy of the government. The paradox of state funding of higher education resides in the fact that although the state has set a limit on the price of dormitory accommodation for students, it does not guarantee any compensation in terms of market prices, leaving the responsibility for finding funds to the “bottom”. Many universities, such as the Lviv National Academy of Arts, pay for utilities from a special fund, i.e. using tuition fees or other fee-based services. However, in some cases, universities lack funding, which leads to debts. A striking example is the Kyiv Aviation University (formerly the National Aviation University), where, due to large debts, the administration decided to conduct a large-scale relocation of students for the winter and closed half of the dormitories because they could not afford to maintain them. However, it is worth adding that charging students an additional fee for utilities with an increased tariff is a unique approach applied specifically to the National Academy. Other universities, although facing difficulties, comply with the law and find money for repairs.

Although the ministries retain significant control functions under the law, when it comes to intervening in situations of violations of students' rights, they avoid doing so referring to “university autonomy”. For example, when students of the Forestry University appealed to the Ministry of Education and Science (MES) to conduct an inspection and take action because of unsatisfactory conditions in their dormitory, the MES simply forwarded their complaint “as appropriate” to the University administration. At the same time, when it comes to reorganizing higher education institutions in order to receive a tranche from the World Bank, the government suddenly ceases to care about “university autonomy” and the legality of its own decisions. This is particularly evident in the case of the Odesa Law Academy, where the reorganization has been partially suspended by the court.

Proclaiming themselves relieved of the responsibility to monitor the protection of students' rights at universities, government officials have not provided them with any tools to protect themselves. When representatives of student self-government complained to Deputy Minister of Education Mykhailo Vynnytsky at a meeting that the administration was not providing them with the funding guaranteed by law, he responded:

“You can either increase confrontation, which will hardly help you achieve the goal, or you may strengthen cooperation, achieve the goal (of allocating funds), while strengthening your own university community. If funds are not allocated, there are reasons for that, so you should analyze those reasons. The Ministry has no means of forcing universities to allocate these funds.”

This raises the question: how to ensure the implementation of the progressive provisions of the Law of Ukraine “On Higher Education”? In my opinion, if the right to student strikes is not guaranteed, student self-government bodies and unions can only defend their rights in underfunded courts, where cases drag on for years. The reason for this is partly due to the fact that protests on university grounds frighten the administration, especially during classes: bureaucrats feel that they do not control the students, that their authority is not recognized. The fear that students will generally stop attending classes and block their studies at the university can significantly change the balance of power and actually contribute to the “student subjectivity” that the deputy minister likes to talk about.

NAOMA students demand to repair the dormitory. Photo: Vlad Kholodov

Conclusion. Practical Lessons from Student Struggle

The struggle at the Academy is far from over, but I, as an activist, have already learned a number of important lessons that I would like to share.

1. Not all student councils and official unions are “yellow”. At NAOMA, we met some very combative and courageous self-government representatives who are not indifferent to the problems of their Academy and need allies. Do not hesitate to get in touch with representatives of student councils; at the very least, it will give you a better understanding of the situation at the university.

2. The more people participate in discussions with the administration, which is not willing to work, the more people realize that negotiations do not yield results and it is necessary to move on to action. Our meetings with the administration in December were not numerous, and when we met with the residents of the dormitory in February, most of them wanted “one more round”. In the end, after the following meeting, the question “ Do we protest?” became “When do we protest?”

3. If there are problems at your university, do not hesitate to look for allies outside of the university and do not remain silent. If Direct Action (Priama Diia) had known about what the dorm students were planning in 2023, the situation would have been positively resolved much earlier. Very often, due to the local nature of our universities, we don't even think that someone else can help us, and this plays into the hands of bureaucrats.

4. Record your victories. The administration often pretends that the actions of students do not affect anything, that all changes occur on their initiative. In reality, however, it is student activism that makes them move. It is crucial that this is understood not only by the direct participants of the movement, but also by external observers. It is necessary to accumulate and share the experience of victories in order to break the stereotype among students that pickets do not lead to something good.

Finally, no matter how much the local leaders pretend to be landed aristocrats, their capital is based on the labor of students, faculty, and technical staff. These groups are the basis of industrial relations at the university, although the administration tries to create a different impression by controlling the educational process, infrastructure, and imposing its bureaucratic regime. If the students question this power, it begins to react hysterically by making calls and threats, however, it eventually collapses so that the bureaucracy has to retreat.

The struggle of the NAOMA students for the right to equal participation in the management of the university continues. But the same struggle continues in other universities, even where it seems at first glance to be completely depoliticized. Greetings to the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

Author: Artem Remizovskyi

Translation from Ukrainian: Anna-Maria Kotlyarova

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva