Ukraine is one of the top ten countries with the most massive outflow of capital abroad. As the Tax Justice Network estimated, in 1991-2012 only, this sum was $167 billion, which is comparable to the annual GDP of Ukraine [Вєдров, 2013]. Globally, offshores contain sums that are equivalent to 30-45 percent of the global GDP.

Below we will try to investigate the historical origins of the “offshore” model of the Ukrainian economy. We will trace the dynamics of the reorientation of Ukrainian producers to global markets and the proliferation of the country’s financial-industrial groups based on this model; we will also outline the scope of the total losses of Ukrainian economy due to the use of such “optimization” schemes.

We will start with a brief review of terminology. In the most general sense, offshores are the financial centers that are located in the territories that offer preferential treatment to foreign companies. According to the OECD guidelines [Harmful tax cooperation], these centers are characterized by:

- zero or minimal corporate tax rate;

- inefficient exchange of information about contractors with other states (for example, between tax authorities);

- opaque legislative, legal and administrative procedures;

- lack of requirements to actually carry out economic activities (allows to avoid doing anything but the operations related to the management of the offshored capital).

Depending on the extent to which these financial centers have the above characteristics, they are placed at a certain point in the range from classic offshores with zero tax rates and maximum secrecy in information handling (such as the British Virgin Islands or Seychelles), to “countries with favorable taxation” (such as the contemporary Cyprus or Ireland).

Another method of tax minimization, which is less discussed in the media, is the use of onshores, which, in turn, are closely linked with offshores. Onshore countries include “high-tax” countries that offer preferential treatment only for some activities (such as asset management) and are useful for constructing agent schemes or registering holding structures. They even include such large and respectable partners of Ukraine as the UK, Switzerland and the Netherlands (every fifth dollar of foreign investment came to Ukraine from these countries). Such activities are less profitable in terms of saving on taxes, but they are more reliable if you need to prove the “respectability” of the owners or to legalize your capital, which was sent out of your home country and accumulated in offshore havens. Indeed, you can rarely hear complaints about capital brought out to or from Switzerland (in contrast to Cyprus), although the origins of such assets are often also dubious. Anyway, such complaints would be hopeless, since Switzerland is the world leader in the financial secrecy index [Financial Secrecy Index, 2015].

Historically speaking, offshores emerged in response to the desire to escape the regulations of the authorities of specific countries, to reduce the fraction of the added value that gets redistributed through national budgets through taxation, and thus to maximize the profits which remained in the hands of the owners. The problem existed even in the Ancient World, when Romans in the Mediterranean area competed for trade routes through their islands by minimizing taxes on those islands [Гамбаров, 2013]. However, offshores really started to flourish in the international economy in the second half of the 20th century. In this period, financial capital, thanks to the accelerated development of communication technologies, acquired the ability to travel between different parts of the world very quickly in search for profitability. The revolution in information technology allowed offshore centers to manage assets and function at a distance. However, let us focus on Ukrainian realities.

The beginning of offshore proliferation and the establishment of Financial-Industrial groups

The restoration of the market economy brought about the revival of the market logic in economic activities. That is why the real offshores came to Ukraine after 1991 as a response to the desire of the new market players to minimize their expenses within the country. But the first legal basis for offshore schemes was laid in the last years of the USSR. For example, the Double Taxation Treaty with Cyprus was signed back in 1982. At that time, it was necessary to sign this treaty to begin foreign trade between the Socialist Bloc and the West; but quite soon, after Ukraine declared independence, Cyprus became one of the central channels for moving money out of the country.

The negotiations about changing the Soviet treaty, promoted as part of the fight against capital outflow, started in 1997, but the new Convention about Avoiding Double Taxation with Cyprus was only signed in 2012 and implemented in 2014. The delay can only be explained by the mutual benefits that the highest authorities of both sides received from these relations. It must be noted that the conditions for offshore transactions with Cyprus have now become worse for post-Soviet entrepreneurs: the increase of the profit tax rate and the harmonization of tax administration were among the conditions for Cyprus to join the EU.

Since the early 1990s, many companies have emerged in Ukraine to provide the services of registering and accompanying capital in tax havens, such as offshore Cyprus. The mechanism has not changed in any significant way in the twenty years that have passed, and the price of such services is relatively low, within the range of a couple of thousand dollars per year, including service. So even a middle-sized company owner can afford to keep their money in offshore zones, saving much greater amounts thanks to undertaxation.

The establishment of schemes for moving capital out of the country is closely linked to the change of the economic system, the transition from state planning to market methods and privatization, which created the material preconditions for the new system. In 1991, Ukraine had the highest centralization and concentration of industrial production, the major part of which produced products which were competitive in the global market [Падалка, 2012]. For example, many machine and instrument making factories in Ukraine in the 1990s disproved the claim that they were “backward” by exporting more than a third of their produce to neighboring and other countries (the Kramatorsk Heavy Machine Building Factory, the Odesa Radial Drilling Machine Factory, the Poltava Artificial Diamond Factory, etc.).

Ukraine also inherited a powerful space potential, which is among the few sectors that still preserve some of the knowledge-intensive production. 140 facilities in this sector employed 200,000 workers who produced a third of the output of the whole space sector of the Soviet Union. A total of 40,000 mid-sized and 6,000 large state-run facilities in Ukraine were estimated to be worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Their de-socialization marked the beginning of the emergence of Ukrainian economic model and the establishment of schemes for moving capitals created in Ukraine out of the country.

The special characteristics of capital accumulation during the 1990s privatization

In 1992, a number of laws were passed that launched the so-called “small privatization,” that is, the privatization of small companies (with up to 100 employees, small sales and not enough capital to create stock companies). At the beginning, there were some attempts by worker collectives to privatize the enterprises that were rented before, especially the “closed joint-stock companies.” However, at the following stages of privatization, these attempts were supplanted by other schemes, which we can now call fraudulent. In 1993, the process of de-socializing industrial giants and strategic facilities began. At the same time, the Decree “On liberalization of external economic activities” was issued, which allowed the creation of incentives for exporting Ukrainian products and tried to control foreign trade and bring it out of the shadow.

The stalling process of privatization and the danger to lose any control over chaotic economic processes forced the government to pause privatization with a moratorium from July 1994 until March 3, 1995. On that day, “The list of companies not subject to privatization” was approved (including energy and fuel, shipbuilding, petroleum processing and other facilities), and so another round of “mass privatization” started. Ukrainians remember this period by privatization certificates [Завершальний етап приватизації в Україні]; this option aimed to legitimize the process, since, in theory, every citizen became an owner of the same number of certificates that provided him with the right to own a fraction of public property. However, in fact, due to the lack of experience with markets and mass poverty, their price was artificially devalued and then sold by financial speculators on the black market. As a result, by the turn of the millennium, 30 million of citizens had lost their property rights, and the new actual owners were now former directors of public companies, speculators, and bureaucratic elites, who concentrated 47 percent of big and middle-sized companies just by buying those certificates. In 1999, the last stage begins, called “the big privatization,” that is, the selling of major public companies, but this time at auctions involving “strategic investors” with certain social and investment guarantees.

The attempts to privatize the agrarian sector were confronted by mass social resistance. As a result, a moratorium on free sales of land resources was introduced, and it is still valid today. In the 1990s, collective farms still existed, but in 1996 they were gradually divided into land plots for the members of their collectives. However, at the time when whole plant and animal farming complexes were ruined, and alternative capital investment was missing, this led to major adverse consequences for the economy and to further degradation of rural areas, up to the replacement of monetary relations by barter and natural exchange of the products of one’s labor in order to survive. In 2000, the situation starts to improve after mass contracting was allowed for agricultural companies producing industrial crops (sunflower, corn, rapeseed, soya). It attracted domestic and foreign investment into agriculture and laid the basis for the agricultural recovery in the 2000s. However, the recovery was not unambiguous, because it led to the degradation of agricultural product market (and the influx of imported goods), to irrational use of land resources. The newly established agricultural corporations soon also joined the offshore trade schemes and, moreover, they manage to pay very few taxes to the government budget [Кравчук О., Одосій О. 2015].

It must be noted that this accelerated market transformation was a response to a direct demand from western creditors, detailed in the numerous memorandums signed with the IMF and other organizations that started to provide loans to the Ukrainian government in that period [Кравчук, 2015]. Even the infrastructure for privatization was funded by international organizations (USAID funded and supported the privatization bills, created networks of privatization auctions in every region). This indicates that western “partners” were interested and involved in the emergence of the contemporary peripheral economic model in Ukraine. It is telling that today, in 2015, the USAID sponsors the technical side of the sales of energy companies that are still publicly owned [USAID, 2015].

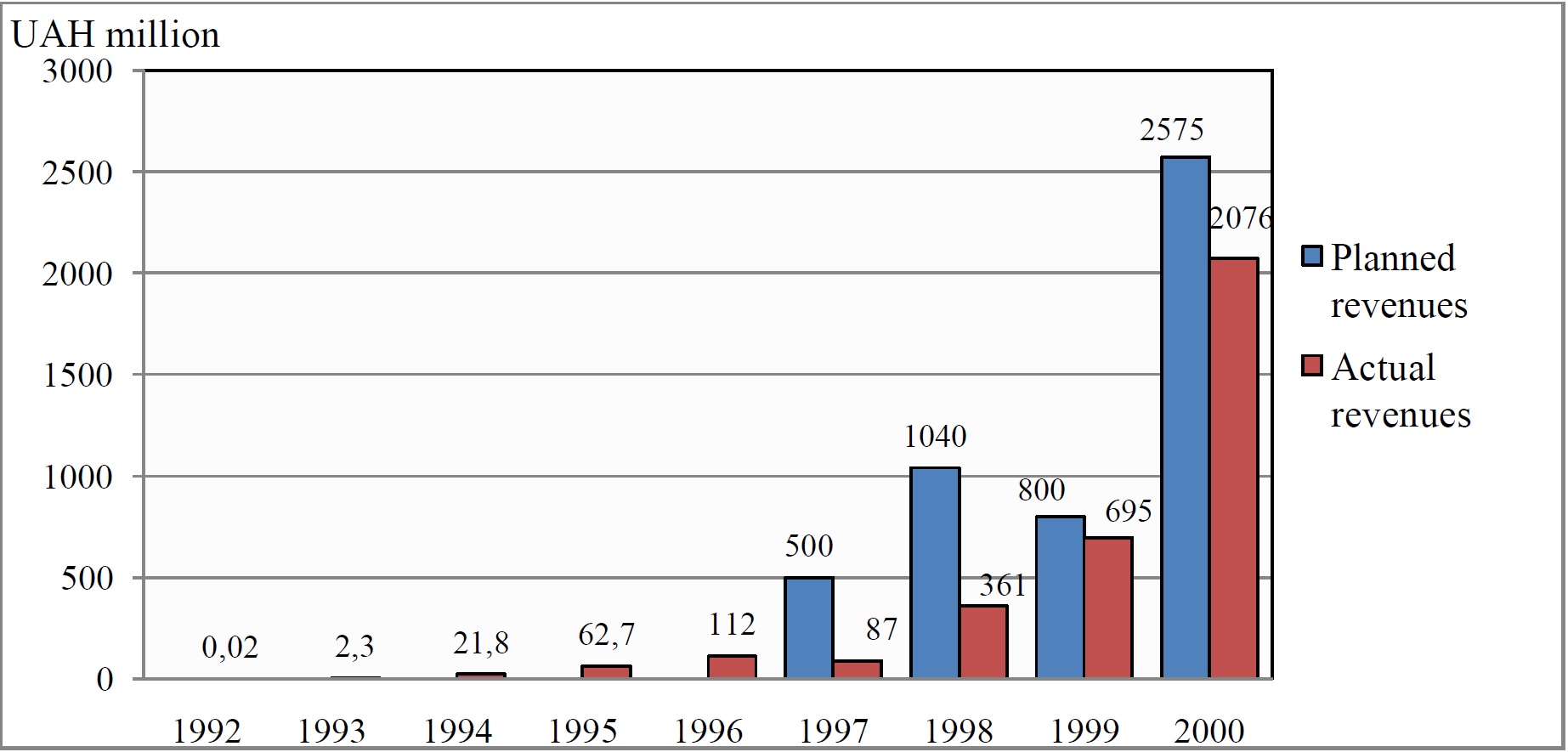

In contrast to, say, the neighboring Poland, where privatization processes were based on international market assessments of property and transparency of procedures (although their efficiency after privatization is questionable), assets in Ukraine were sold at minimum prices and hardly provided anything for the country’s budget (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The planned and the actual amounts of revenues received by the Ukrainian budget from the privatization of public assets in 1992-2000 [based on the data by the Public Property Fund of Ukraine].

Therefore, by the late 1990s, the economic transformation created large financial and industrial groups (FIGs) that acquired control over the most profitable industries: electricity production, metallurgy, chemical industry, etc.

The Ukrainian situation was characterized by the prevalence of financial/banking capital, which formed earlier than industrial capital. Private banks claimed and often obtained the right to privatize industrial giants (that was what happened to Aton, the Energy Systems of Ukraine). Later, these financial-industrial groups would start to fight for power in the government and distribute government bodies among themselves using resources in favor of various FIGs.

The issue of privatization of the rest of the strategic companies (Odesa Port Factory, energy generating and distributing facilities, Kryvorizhstal, Azovstal) will become one of the key reasons of a number of political crises in the country. There is even a special law “On financial and industrial groups,” aimed to lobby their interests, but also involving greater control over them. However, it was cancelled in 2005 (only one financial and industrial group called Titan was registered, although a couple of financial and industrial groups de facto controlled and still control whole economic sectors).

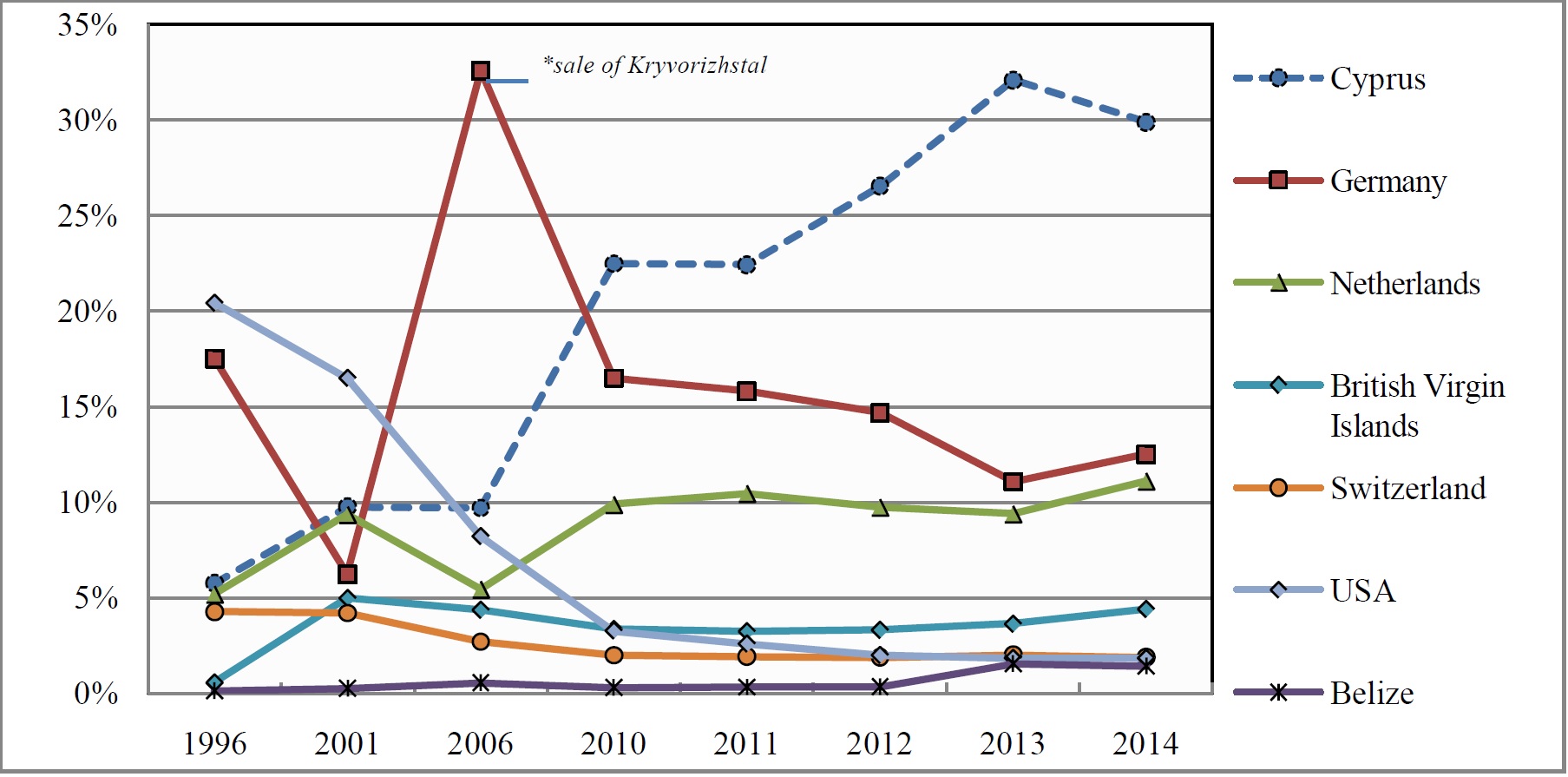

However, despite the explosive emergence of the new class of owners on the ruins of the old industry, the processes of offshorization had not yet reached alarming proportions by the end of the 1990s. It is proven by the data on investment into offshore zones (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The dynamics of foreign direct investment from various countries into Ukraine in 1996-2014, cumulative total [based on the data by the State Statistics Service].

As the figure demonstrates, offshores (primarily Cyprus) started to rapidly become more important after 2006. In the case of the key offshore partner of Ukraine, Cyprus, the fraction of investment there increased to 22 percent in 2006-10, in the years when Ukrainian companies increased their exports.

But, of course, oligarchic business, which grew up closely related to and protected by the state, looked for other ways. How could they hide their superprofits from exploiting the assets they bought for garbage prices, and the workers that were forced to work for miniscule compensation? The ways to do that were soon discovered.

Free economic zones as an alternative means for hiding profits

In 1998, free economic zones (FEZs) and priority development areas (PDAs) started to become widespread in Ukraine. In the same year, a number of laws were passed to provide broad tax preferences. Companies located in these zones were relieved of duty fees for their imports, and were relieved of or had preferences in paying income taxes and the VAT, could choose not to sell their foreign currency revenues from exports, excise fees, land fees, and so on.

These zones were created on the national level and were justified by higher goals of attracting investment into depressed regions, developing the productive forces of the country and introducing high-tech manufacturing. In the end, 12 free economic zones and 464 priority development areas were created. These zones covered more than 20 percent of the country’s territory (10.5 percent under the FEZs, and 10.3 percent under the PDAs). Most investments into these zones was imported into Ukraine from offshores. For example, 41 percent of investment into Donetsk FEZ and PDA were drawn from Cyprus, and another 6.4 percent from offshore Virgin Islands [Національний інститут стратегічних досліджень, 2007].

This meant that the Ukrainian capitals previously sent out to offshores were brought back without any import duties or taxes, which is one of the ways to minimize taxation. Even though some of these projects actually aimed to create new jobs and modernize industries (the construction of the petroleum processing plant in Mariupol funded by investment from Cyprus, the modernization of metal processing complex Isteel funded by investment from Virgin Islands, etc.), this kind of investment in the situation when any balanced government policy was lacking usually happened in low-tech processing industries.

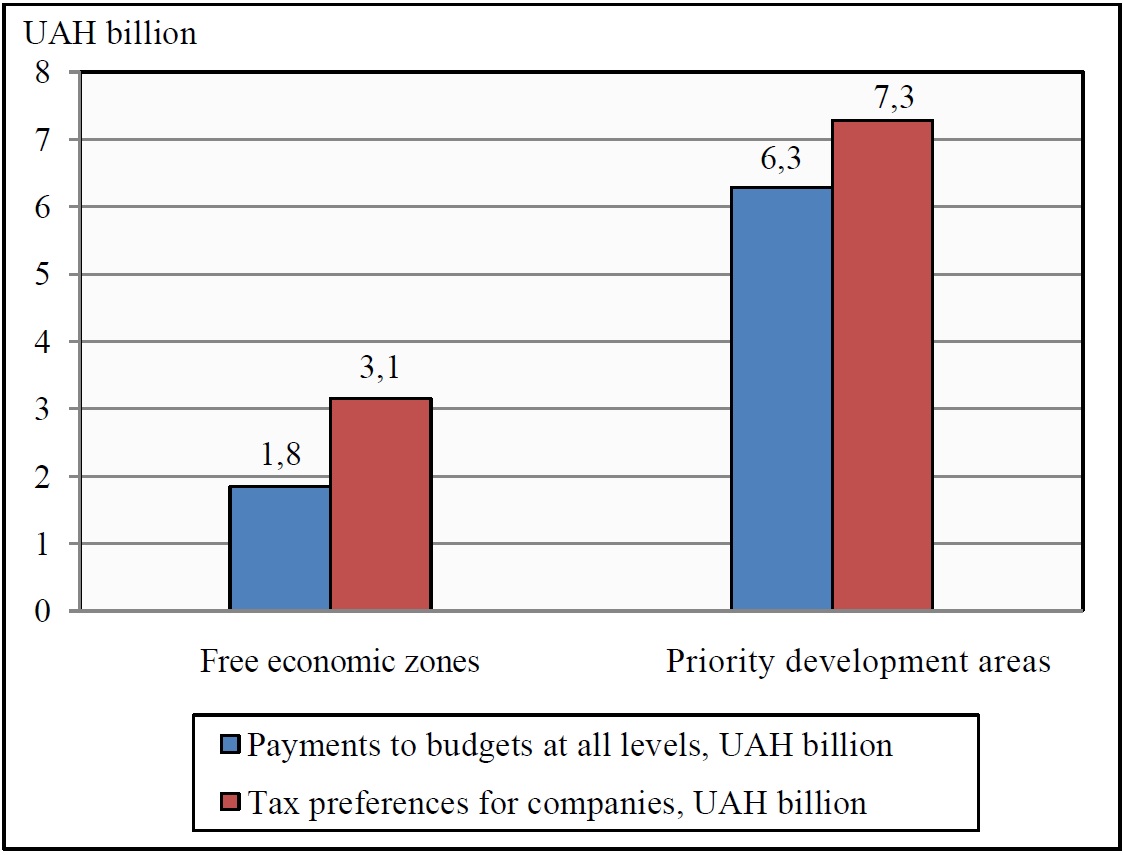

As a result, the Ukrainian economy was fixed in the position of an exporter of raw materials, while other options for social development and social security lacked funding. Therefore, in practice, these companies served as “tax-free openings” and allowed to abuse Ukrainian resources for profit. The data of our analysis also prove this (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The relation of tax preferences provided to FEZs and PDAs in Ukraine to tax revenues, as of 2007 [based on the data from NISR].

The figure demonstrates that free economic zones and priority development areas received a total of UAH 10.43 billion from tax preferences, and provided only UAH 8.14 billion to the government budget. The index of budget efficiency for FEZs was UAH 0.59 per one hryvnia of benefits; PDAs fared a little better, UAH 0.86 per one hryvnia; together, they provided UAH 0.78 per each hryvnia of tax benefits. For example, one hryvnia of tax benefits for the Donetsk FEZ brought the government only 0.06 of a hryvnia in tax revenue. The growth rate of the output of these zones and areas was only slightly higher than the average growth rate in their regions in 2000-6 (145.5 percent vs. 131.3 percent). Major violations of the procedures of quality testing and the national standards have been found in these zones. The fraction of investment into free economic zones, despite the expectations, was only 10 percent of all foreign investment into the country.

Many companies limited their activities to the duty free trade of imported goods, which means that they existed only to avoid payments to the government budget. That is why in 2005 the conditions of operation of FEZs and PDAs were radically changed, and benefits and preferences for such companies were limited.

In 2005, tax evasion via offshore zones started to gather momentum. Offshore zones are just another type of free economic zones, but they are located in other countries.

The entrenchment of the offshore model of big business in Ukraine

As Table 1 demonstrates, since 2007, major capital investments by Ukrainian companies have been recorded in Cyprus, which has accumulated more than 90% of the total investment from Ukraine.

Table 3.1

[according to the State Statistics Service]

If we go back to Figure 2, we will see that in the same period the capital that flowed out to Cyprus was partially brought back to Ukraine. The fifth line in Table 1 demonstrates that investment from Cyprus was more than two times higher than the recorded capital transferred from Ukraine to that country. The probable reasons are that offshore flows are redistributed between many zones, and that some money was sent out of Ukraine not as investment but as exports for lowered prices and as imported fictitious services (royalties, dividends, etc.), which are some of the most popular schemes for pumping resources out of the country. We will discuss the analysis of these phenomena in the next sections of this book.

The table also demonstrates a downward trend in foreign investment from Ukraine: $6.2 billion of assets by the end of September 2015, which is 10 percent less than the sum in 2012. The trend of foreign investment into Ukraine is even more typical; it has turned into a true capital flight. Thus, by the end of the 3rd quarter of 2015, foreign direct investment into Ukraine shrunk to $43.95 billion, which is a quarter less than the $58.16 billion invested into Ukrainian companies in 2013 [Держкомстат]. Of course, what else we can expect in an unstable economic situation and during a military conflict.

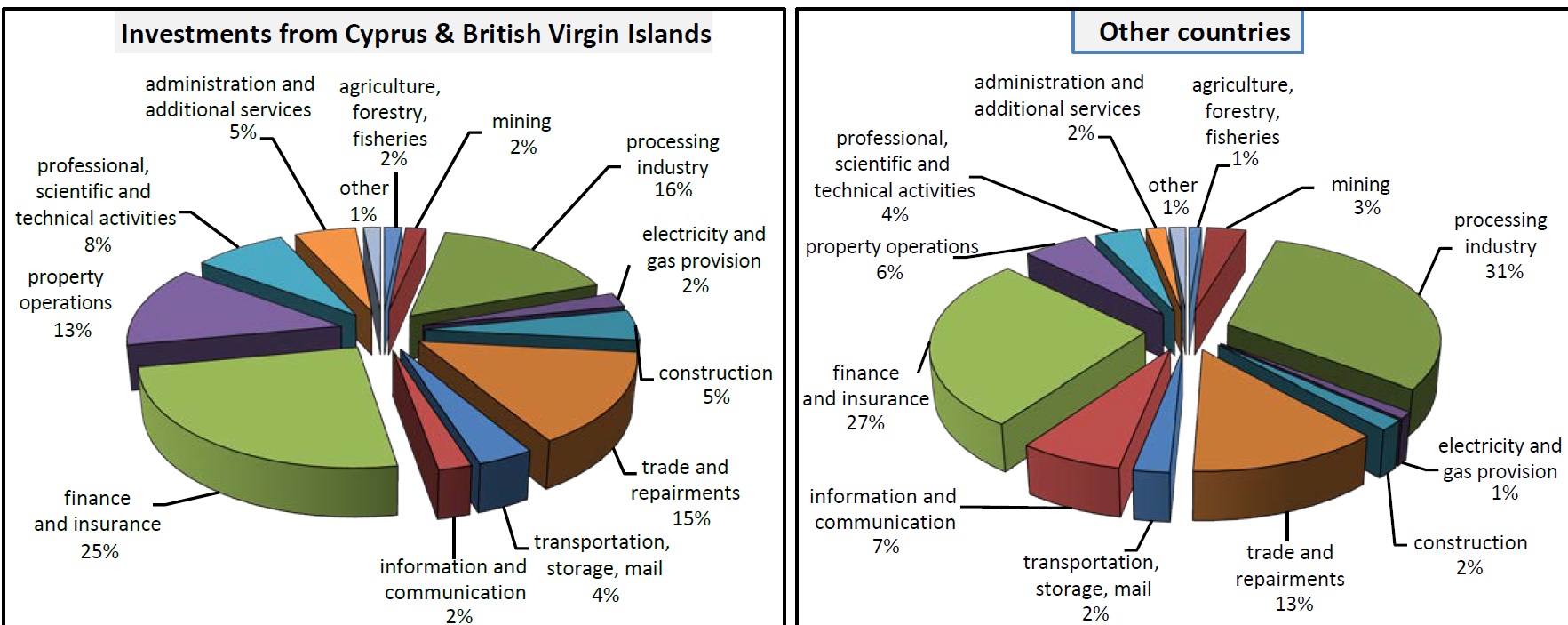

It is reasonable to analyse the structure of investment into Ukrainian economy and compare it to the offshores (Cyprus and the British Virgin Islands, which invested $14 billion, 32 percent of all foreign investment into Ukraine) and other countries (Fig. 3.4-3.5).

The analysis demonstrates considerable differences in investment:

- Offshores invest three times less into the processing industry, and even two times less into the mining industry, than the average for the rest of investor countries.

- The fraction of investment into professional, technical and scientific activities ($1.1 billion) from offshores is twice as big as from other countries, which can indicate abuse of fictitious services.

- Construction in Ukraine is mostly funded by offshore investment (the fraction of this kind of investment is almost three times higher.

- Interestingly, almost a half, 48 percent, of investment from the Virgin Islands ($883 billion) is an investment into trade and repairments.

Figures 4, 5. Foreign direct investment into Ukraine by industry, as of September 30, 2015, cumulative total [based on the data from State Statistics Service].

Ukraine’s trade, which we do not cover in this book for the reasons of space, has been going through offshore centers and countries with favorable tax treatment, at least until recently. It is also confirmed by the State Fiscal Service. According to the Service, about 52 percent of exports from Ukraine went through intermediaries and 13.8 percent of those through offshore zones. This means that a major part of surplus value produced by Ukrainian companies flows out of Ukraine, that is, escapes its tax authorities, and then is re-sold to the countries that actually consume these products [Собуцький, 2012]. For example, in metal processing industry, more than 75 percent (UAH 64.7 billion) of operations are carried out through intermediaries. The situation in the grain market is even more threatening: according to the tax authorities, more than 98 percent of exports in this sphere use intermediary companies which are often connected to each other (see the analysis for specific industries below in Sections 3.2 and 3.3).

Contemporary use of offshores by Ukrainian companies

Since 2014, Ukrainian exports and imports have been actively diverting from traditional offshores. For example, the total value of all goods exported to Cyprus in this period is less than $50 million, which is five times less than in the same period of 2014; the trade through Belize and British Virgin Islands has practically come to a halt (while as recently as in 2013, $175 and $385 million worth of goods, respectively, were exported to these countries). The trend in the service sector is similar, albeit less abrupt; for the first 9 months of 2015, the exports of services to Cyprus and the British Virgin Islands fell by 43 percent, and the imports from these countries fell by 36.4 percent. All of this happens as the volumes of Ukrainian foreign trade are shrinking rapidly. By the end of the 3rd quarter of 2015, the total export of goods from Ukraine fell by 32.7 percent (to $28.1 billion), and the total import by 33.6 percent (to $26.4 billion). The export and import of services fell by 20 percent in the first nine months of 2015. Even though this is not the key factor of reduced offshore trade, it undoubtedly impacted the use of offshore zones as intermediaries. In any case, without a systematic solution, the problem of capital outflow will remain a threat to the country’s further development.

Ukrainian government plans to fill its budget by denouncing the Treaty with Cyprus [УНІАН, 2014] (actually, this is one of the IMF demands); however, after the adoption of the new Convention, which is more strict about tax minimization, and after the recent bank crisis in this country, Ukrainian capital is looking for safer and more profitable tax havens anyway. This logically entails the question, Are offshores an invincible evil, and can the struggle against them be effective?

Fighting offshores: international and Ukrainian experience

First of all, we must mention that we believe that the problem of capital hiding is impossible to solve without replacing the whole system of commodity and money economy with a more progressive method of distributing resources. However, even today, even within the contemporary market system, the problem can be considerably reduced, if not eradicated.

At the turn of the 1980s and the 1990s, when the process of unchecked capital accumulation was rampant in Ukraine, developed countries started to fight against offshores. In 1989, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) was created, which focuses on capital outflow to offshore havens. This organization, which operates on the international level, successfully demanded that Ukraine signed a law on implementing the famous 40 recommendations to fight money laundering [Financial Action Task Force, Закон України «Про запобігання та протидію легалізації доходів»].

In 1998, the abovementioned Report by the most developed OECD countries was published; the Report brought the fight against offshores to a new level. Today, much attention is paid to implementing international agreements about tax information exchange. In 2010, the USA signed the unilateral Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act [FATCA], which introduced financial sanctions for banks that refuse to reveal information about the accounts of US residents. In 2014, OECD countries agreed to a similar exchange of tax information since 2017, which is promoted as an opportunity to fight illegal capital outflow from these countries [OECD, 2014]. It should be noted that less developed countries have to comply with fewer demands of this kind.

The reason might be that the key offshore centers are created on the territories directly or indirectly controlled by these countries, and, in addition to loans, they are one of the instruments of global resource redistribution. As a result, offshores contain 17-20 percent of capital from developed countries, which is two times less than from developing countries (about 40 percent).

As for Ukraine, it has also passed some legislation since 2000 that introduced serious responsibility and control over foreign trade. In particular, currency control was strengthened, the right of offshore companies to privatize Ukrainian companies was limited, the rules for fighting unfair pricing of imported goods were detailed, and fines for capital repatriation into offshores were introduced, etc. [Гаркуша В.]. However, since stopping these flows of capital would endanger a whole class of beneficiaries who directly influence political processes, these attempts were negated, or other, more elegant methods of surpassing the law were invented. Even the story of Cyprus, which was included into and excluded from the list of offshore zones a couple of times, proves this point. In 2015, Ukrainian government expanded the list of countries (territories) under control to include 75 items [Розпорядження КМУ від 14 травня 2015].

There were attempts to implement the Law on Transfer Pricing, which is strongly resisted by major importers and exporters and has not started to work properly.

Thus, as we can see, the issue of capital outflow from the Ukrainian economy is one of the most urgent issues to resolve in order to provide the country with growth opportunities. This topic has to be investigated in detail, and the appropriate mechanisms of fighting the resource outflow should be implemented.