On February 24, 2022, when Russia yet again invaded Ukraine, it was already one of the poorest and most indebted countries in Europe, at war since 2014. Its needs and losses have grown exponentially – dislocation of the labour force, infrastructure destruction, ecological damage, etc. This article argues a case for large-scale multi-faceted international assistance, debt cancellation, and “fiscal activism” as preconditions to (re)building a resilient and sustainable economy; to making a Ukraine that millions are fighting, many died and suffer for a reality.

Intro: state of affairs, role of context

On February 24, 2022, when Russia yet again invaded Ukraine, the latter was already one of the poorest and most indebted countries in Europe, weathered by “transition to market” and associated “unintended consequences”, numerous economic crises, and nearly 8 years of war with Russia and its proxies in Donbas and Crimea. Budgetary expenditure on arms, humanitarian needs, and medical needs (of the wounded) have grown exponentially. The scale of GDP contraction in April 2022 already was projected by the World Bank at 45%[1] while poverty rate projection for 2023 was at 58% year on year increase – and by now those actual figures will be higher despite recent optimistic figure updates. Money is needed to reconstruct Ukraine’s homes and infrastructure; clean up, de-mine, and decontaminate cities and countryside. Ukraine is losing industrial and agricultural capacity, imports/exports are disrupted, and industries are leaking cadre due to displacement, refugee flows, impairments (physical and mental traumas), and death. Russian Federation will have to pay for the ruination; proposals and actions are being discussed yet the destiny of frozen assets, setting up repossessing/reparations mechanisms and more will not likely happen until Ukraine’s victory. So, for now I want to focus on the losses Ukraine sustained to date set against the backdrop of constraints and opportunities set out in the post-war reconstruction plan presented in Lugano on 4-5 July 2022.

Volodymyr Zelenskyi made a speech at the Conference on Restoration of Ukraine held in Lugano. Photo: Alessandro Della Valle/Keystone/dpa/picture alliance

Social losses and economic de-development: war damage and (pre)war reforms

The full scale of losses will only be known upon full withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine’s constitutional borders. The deep essence of concepts of “value” and “price” take on their most visceral forms when one stares in the face of a genocidal war carried out by a death cult regime. Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Ukraine “estimated US$46 billion and still rising—includes direct war damage to air, forests, soil and water; remnants and pollution from the use of weapons and military equipment; and contamination from the shelling of thousands of facilities holding toxic and hazardous materials”, The long term impact of losses to and of the ecosystems is impossible to quantify especially since Ukraine “contains habitats that are home to 35% of Europe's biodiversity, including 70,000 plant and animal species, many of them rare, relict, and endemic”.

Ukraine needs external aid of roughly $4 billion per month to support the war effort and sustain essential public services while the need for budgetary support for 2023 is at $38 billion. The damage is so severe that even the usual advocates of market solutions to market and nonmarket problems e.g. Eichengreen and Rashkovan, call for grants and debt relief. By the end of 2022, the total amount of documented damage to Ukraine’s infrastructure was estimated at $137.8 billion (at replacement cost). Since autumn 2022, all thermal and hydropower stations have been damaged, by February about a third of all power generation and distribution capacity is lost; “at least twice during these attacks, Ukrainian nuclear power plants lost connection to the grid, posing nuclear safety risks”. Being a major global grain exporter, the loss of 40% of production in 2022 is and will be felt in Ukraine and abroad, especially in low-income countries. Reduction in rural household food production of 25-38% (depending on proximity to frontlines) normally responsible for 25% of total country output is too felt in supply reduction and in price inflation[2]. In the early days of the invasion in 2022 “Russia must pay” project was launched to document war damages upon Ukrainian economy; the results and analysis are published on damaged.in.ua website and are updated regularly[3].

Table 1. Total damages, monetary terms (Dec ‘22-Jan ‘23 at replacement cost), $bn

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

Source: KSE (2023)

Ukraine in and postwar rebuilding tasks sit against the challenges of financial, demographic, and institutional capacity being uncertain. Further complications arise when we assess the “externalities” of the war alongside the “unintended consequences” of the market reform Ukraine went through since 1991 (corruption and oligarchs as part and parcel but not the only ill of it), is implementing now and plans more of after the war (see Lugano plan and labour reform below). In the process of “transition to market” since 1991 Ukraine has suffered large scale de-development i.e., its foundational economy, its public services and infrastructure have deteriorated and suffered from systemic and chronic underfunding. This resulted, among other, into socialisation and individualisation of costs of meeting the needs previously catered by those state funded services and/or those services altogether lacking or being of reduced supply with notable regional variegation. Discursive normalisation of those changes and responsibilisation of the populace for this combination of state and market failures became an additional ideological stumbling bloc in the way of increasingly agitated civil society’s efforts to address the symptomatic results of those failures e.g. demands for full private healthcare provision instead of fully deployed and state funded system. While these problems often get blamed on mismanagement, corruption and embezzlement, they have more to do with a combination of the “costs” of the EU rapprochement reform, budgetary constraints, IMF Structural Adjustment Loans conditionality, and similar limitations on fiscal policy choices that straightjacket even the most well-meaning state administrators as is evidenced by similar experiences of numerous other countries.

It is hard to be precise about the social losses and damages too, not unlike economic albeit for different reasons yet it is the individual struggles that are most revealing of the gaps in state and market provision like, tell us where the rebuilding effort will be most needed. The compound and complex effects of the 9 year-long war especially for IDPs and refugees reveal pre-existing capitalist and patriarchal reproductive inequalities which have been exacerbated by displacement with variegated effects and severity. Access to adequate resources (inc. cash) and (child)care, suitable & stable housing are acute issues for IDPs (and also those who stayed at home). Real estate and particularly rental markets are poorly regulated, rental prices in cities considered relatively safe have magnified overnight while availability is low. This leads to three forms of displacement: “displacement caused by the dangers of war, displacement caused by destruction of homes, and displacement caused by the rent market itself”. A comprehensive state funded housing programme is needed which may be tricky if the role and function of the state in the Recovery Plan is not reimagined. Most Ukrainians can’t afford inflated mortgage and rental market properties, nor to upgrade the old Soviet stock that was depleted by 3 decades of poor municipal investment and recently the wars.

Refugees at the Lviv railway station, March 9, 2022. Photo: Darya Bedernichek

Schools and kindergartens being bombed, education and care for children provision are extremely challenging which is made worse by pre-existing problems in those sectors – from chronic underfunding and understaffing to low wages of the employees and parents struggling financially, especially in single parent (mainly mother) households.

The situation with employment and income amidst displacement, shelling, and inflation is too highly challenging. Accurate data is lacking but what is clear is that things are getting worse. Djankov, S. and O. Blinov (17 Nov 2022) use wage payments data from one of Ukraine’s largest commercial banks to get a picture:

“Since the start of the war, nominal wages have managed modest growth, amounting to 3% by end-October. However, wages dropped 11% in real terms over the January to October period and their decline has accelerated to 18% in the past month”. Moreover, “13% of hired employees have lost their job since the start of the war and there is evidence of increasing job losses.”

This is amidst YOY inflation in 2022 alone going to 26.6% from 10% end of 2021; in pre-pandemic 2019 it was 4%. To top it all, instead of protecting the rights of people in wartime, antilabour laws in mid-2022 stripped some 70% of workers of labour code protection. According to labour lawyer and the leader of the Sotsialnyi Rukh organisation Vitaliy Dudin, the changes “affect workplaces with hundreds of workers, including public sector jobs at risk of austerity policies, such as hospitals, railway depots, post offices and infrastructure maintenance”.

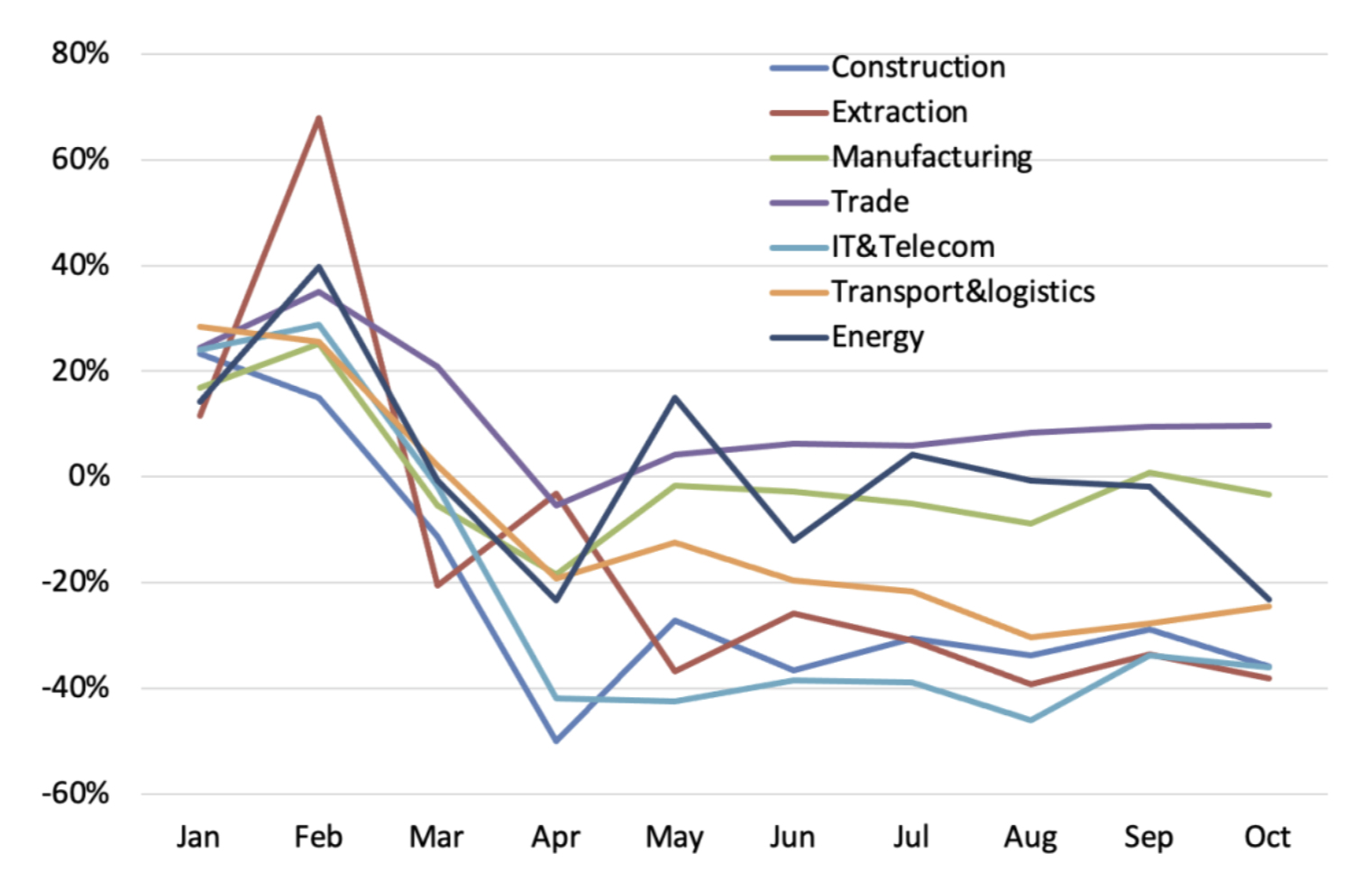

Figure 1: Productive economy average nominal wage, year-on-year change in 2022

Source: Djankov, S. and O. Blinov (17 Nov 2022)

Jobs are being lost, savings are depleted, credit cards maxed out; many struggle to service their debts, and even more will struggle having access to credit finance now and in the future, due to access criteria/costs and availability alike. This, never minds the unfairness of household debt accumulation, is why this debt must be written off as part of the (post)war recovery approach – an economy cannot run on a mix of good will of increasingly poorer friends/relatives and sporadic local and foreign donations to food, meds, and clothes collections. A set of comprehensive policies must be developed, a complete overhaul of the problems that existed before the 2014 and 2022 invasions which exacerbated those problems but did not create them.

Debt politics amidst socio-economic upheaval and erosion of sovereignty

Chaotic borrowing and debt explosion in Ukraine over the years was partly a result of oligarchic state capture and kleptocracy. IFI loans were issued under conditions of social spending cuts, economising on vital needs. The country’s debt demand context was characterised by the loss of a real economic base at a rate disproportionate to the growth required to maintain the health of the economy or honour debts, state or private. Debt increased up to 5 times denominated in UAH mostly due to dollarisation, Euroization, and high value-added goods import dependency. Until the summer 2022 Ukraine adhered to its debt obligations. Between February 24 to October 2, 2022, “the amount of funds paid by the government for the repayment of domestic debt instruments by UAH 54,093.9 million exceeds the amount of funds raised in the state budget at auctions for the sale of government domestic loan bonds”. Clearly an alternative form of financing is needed – more grants, not more loans concealed as aid.

A temporary suspension of debt servicing has been agreed between Ukraine, The Paris Club and G7 on July 20, 2022, and signed on Sept 14, 2022, for 1 year as of Aug 1, 2022, with a possible extension for one more year (decision affecting about 75% of all foreign debt) – not least due to multipartite international civil society campaigning. Yet this is insufficient; not least since IMF debt conditionality is firmly in place and debt surcharges are still to be paid.

Volodymyr Zelenskyi addressed the G7 leaders, December 2022. Photo: Office of the President

In Ukraine’s case, historically conditioned relationship with EU/western partners and Russia (mainly), economic and geopolitical, add extra dimensions of simultaneous complexity and fragility, via debt, trade arrears, and import/export dependencies. Debt as an instrument of external control and expropriation of national wealth, combined with the modern system of taxation and trade regimes is a powerful diluter of the decision-making autonomy fundamental for any meaningful exercise of political sovereignty. Debt leads to “alienation of the state,” that is, the national state ceases to be an autonomous agent of authority and representation of its people’s will. Ukraine had to engage in war bonds sale and utilise numerous rapid financing mechanisms available internationally to fund the war effort where aid was insufficient, each coming with its conditions and more constraints.

Reconstruction plan and EU prospects – what can make it a success?

In Lugano, Switzerland on July 4-5, 2022, the Ukraine Recovery Conference URC2022 outlined dimensions for Ukraine’s revival which sounds promising yet the means don’t match the aims i.e. the state will struggle to finance or attract enough private investment/direct it where it is most needed – the whole of $750 billion of it so far. Discussions revolve around it being modelled on the Marshall Plan which was a success due to cash grants and loans and recipient discretion in spending. The European countries often used this money to buy essential goods like wheat and oil and to reconstruct factories and housing. A like plan for Ukraine would need to be (re)designed and executed in alignment with the best practice and standards of EU labour right, public services and environmental protection; for that to happen a number of changes I outline below need to occur.

Prime Minister of Ukraine Denys Shmyhal (center) at the Conference on Restoration of Ukraine held in Lugano. Photo: Denis Shmyhal/Twitter

Ukraine’s extraordinary situation presents a case for large-scale multi-faceted international assistance, state and household debt cancellation, and conditionality of new loans rewriting to facilitate “fiscal activism” i.e., measures aimed at stabilising business cycles via discretionary use of fiscal policy. Austerity is uneconomical and unecological even at peacetime, let alone at war. What is needed is full state-funded (re)development of public services and care economy – with a radical internalisation of positive externalities into assessment of state investment returns – which must become mainstream political discourse in Ukraine and among its international partners. The state in Ukraine is not bloated, unlike its stereotypical perception,but on the contrary – "the share of national income distributed through taxation and budgetary allocation in Ukraine is much smaller than in advanced economies of the EU”. State was the key agent in rebuilding much of Europe, Japan and South Korea after World War II – the "developmental state" was elaborated as a concept, and now is the time to return to it as “free” markets fail especially at wartime. Principles of the European Green Deal and beyond with the state at the centre of recovery is what is needed.

IMF and other creditors are needed as sources of financing. But it is state institutions that carry out the recovery and should have “the ownership of the reconstruction process”. Moreover, the key role of civil society (NGOs and trade unions, the latter being often left out) delivering where state and markets alike failed since 2014 must be acknowledged, scaffolded, and financed by the state instead of international crowd-funders – such polycentric form of the governance (Ostrom) and the state as institutional network can deliver the rebuilding Ukrainians envisage; it can also allow the principles of deep sustainability reflected in the Lugano Recovery Plan become a reality by treating economy as a socio-ecological system rather than a sum of economic fragments. Local enterprises should have priority over the foreign. The economic policy consensus has shifted globally to favour (post)Keynesian vision of state-led investment in own economies to boost confidence and kick-start the multiplier effect, while SAPs have been criticised by IMF own research as limiting on macroeconomic growth, the de facto relationships with the Fund’s borrowers have not changed, they since were renamed “conditionality” but in essence have not become less rigid, increased in fact; those debts and their conditionalities must be cancelled.

Volodymyr Zelenskyi talks with IMF representatives. Photo: International Monetary Fund

Ukraine will need green/low carbon job creation (e.g., care economy, arts, education, environmental preservation & sustainable R&D, etc.), just transition, and energy democracy which will maximise possibilities for its economic self-sufficiency and reduce import dependency of key industries. Job creation is key as millions of Ukrainians work abroad seasonally, more now have left the country etc – by 2017 7-9 million left the country to work abroad, 3.3 million between 2011-21 alone, “while their families remained in Ukraine. The inflow of remittances to Ukraine in 2020 reached $12.1 billion”. While those transactions support Ukraine’s economy, they are hardly an indicator of good quality of life for average citizens whose lives are destabilised. In 2021 alone 660,302 persons left the country amidst challenges exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Vast numbers fled the country since the invasion of Feb 24, 2022. Conditions must be created for people to be able to come back and will need to range from infrastructure and (social) housing (re)building (including whole towns in some cases) and sustainable job creation across Ukraine. Surveys, multiple journalistic articles and reports, and anecdotal evidence all point out to Ukrainians’ will to return to Ukraine once (1) it is safe and (2) once they have somewhere to go back to, many return even without certain jobs nor survival guarantees.

EU integration can become a saving grace for Ukraine’s economy or it can become a force for further de-development and peripherilisation. Lessons from experiences of other economically weaker and newer member states here is key and it has been observed that integration processes are a game rigged against EU periphery countries. Ukraine’s situation is extraordinary not least due to its membership path laid through the debris of a genocidal war for which rapprochement with the EU and NATO were used as a pretext. Moreover, from the outset the demographic, economic, institutional, and ecological tasks at hand are stupendous even judged by standards of an advanced peacetime economy. This sets context for equally extraordinary arrangement of the rules of engagement of which many are already underway; yet many are bigger in aims than in means proposed. For recovery to become what was outlined in Lugano, a fundamental rewriting of the global debt and policy conditionality regime, the “black holes” of offshore, tax avoidance and evasion including transfer pricing must disappear. Further, a proposal can be made of a potential plan-case to follow for construction for similar economies globally. We need to think beyond Ukraine, we need to think Ukraine as part of the global economy, and we need to be thinking alternative economic systems altogether built by and for noospheric societies – societies of the era of reason where wars, poverty, and ecocide are made impossible by design.

Footnotes

- ^ This has been updated for a better projection since yet there are few reasons for optimism.

- ^ This includes “approximately 85 percent of fruit and vegetable production, 81 percent of milk and around half of livestock production” (FAO 2023: 1).

- ^ The data is collected to be used (1) “to document war crimes and human rights violations; (2) for the formation of claims against the Russian Federation in international courts for compensation for damage caused: lawsuits for international courts require aggregate evidence and a register of damaged objects in accordance of the methodology of estimating; (3) for individual compensation; (3) to receive war reparations and compensations for damage from the aggressor for the reconstruction of Ukraine”.

Author: Yuliya Yurchenko

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva

The article is based on a chapter from the book "Europe and the War in Ukraine: From Russian Aggression to a New Eastern Policy". The Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS) edition will be published in June 2023.