Those Ukrainians who feel optimistic, can celebrate the growth of the national economy. The State Statistics Service of Ukraine has finally reported that the gross domestic product exceeded the level of the first quarter of 2015 by 0.1%. This is a remarkable achievement, and the Ukrainian media are highlighting it as a confirmation of the forecasts of a long-awaited recovery of the national economy. We also want to be optimistic and we understand that the bottom must be reached at some point. However, it is important to ask why the mainstream media fail to focus on the complex changes that have taken place in the country's economy and production structure, all of which will affect the possibility and nature of the Ukrainian economy's development in the future. After all, two years after the change in the country's general course, is enough time to draw first conclusions.

Thus, we analyze the trends of general economic development; examine the structural changes in certain industries and the reformatting of the banking system and changes in financial policy; determine the consequences of the implementation of the Association Agreement with the European Union and how all these factors have affected the redistribution of resources through changes in the country's budget policy.

The first article focuses on general and structural changes in the Ukrainian economy.

General overview of the economic situation

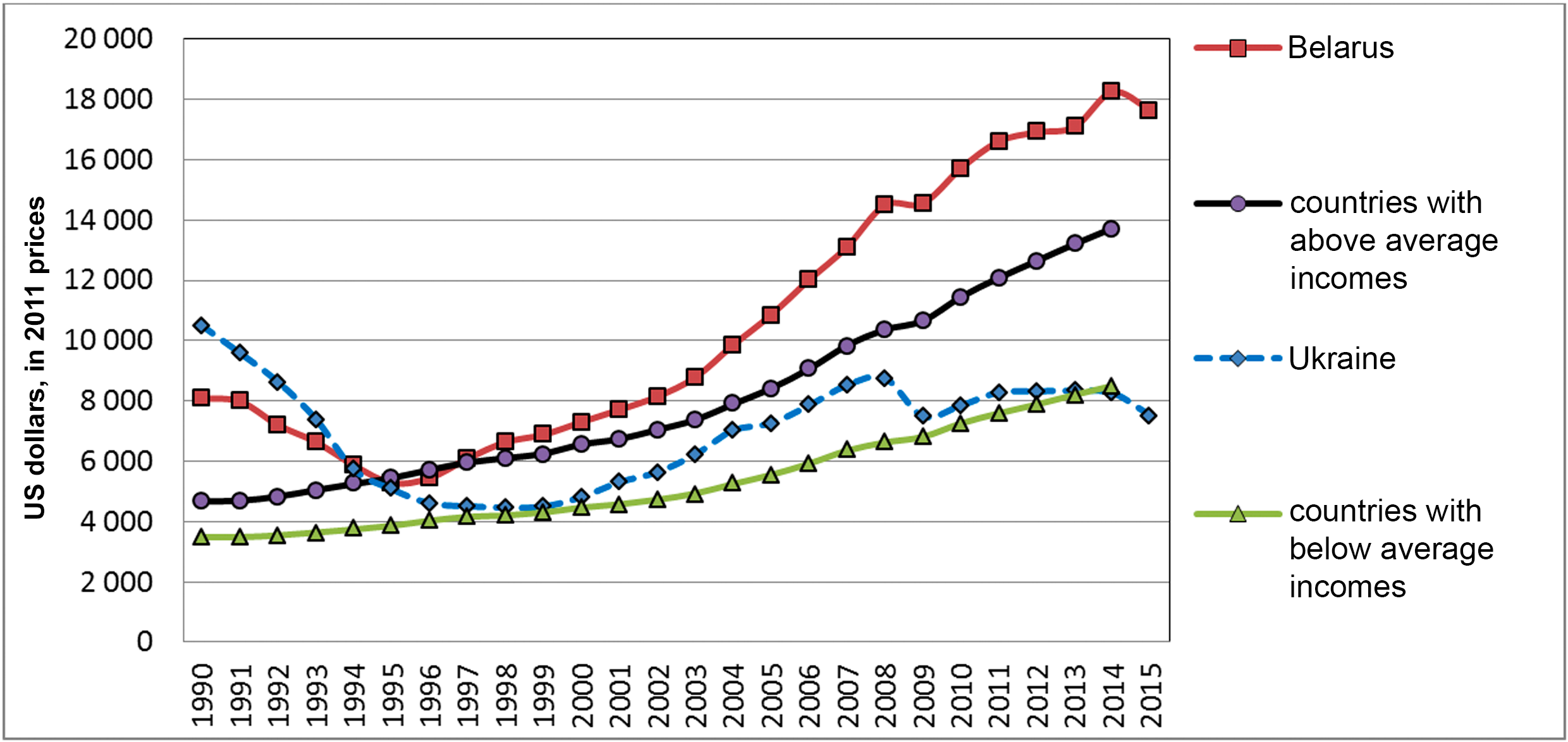

Unfortunately, the per capita production of goods and services in Ukraine has been consistently declining since 2014[1] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dynamics of Ukraine's GDP in terms of purchasing power parity per capita in comparison with other countries [based on the methodology and data of the World Bank, the State Statistics Service of Ukraine, the National Statistics Committee of Belarus]

As we can see from the figure, over the past 25 years, Ukraine has been moving towards the cohort of the poorest countries in terms of output per capita. While in 1990 this indicator corresponded to the levels of Poland, South Africa, and Malaysia, in the 1990s Ukraine went down first to the category of countries with above-average incomes, and then to the category of countries with below-average incomes. By the end of 2015, GDP per capita fell to 8.5 thousand US dollars per year (117th place in the world). We also show the Belarusian dynamics to demonstrate that Ukraine’s trend is not something unavoidable for post-Soviet countries. As we can see from the figure, even the less developed and resource-rich economy of Belarus managed to double its total output, unlike its southern neighbor.

As a result, Ukraine's share of global output (and thus its influence in the international arena) has decreased by more than 4 times, from 1.3% to 0.3% [World Bank, State Statistics Service]. However, one should bear in mind that a significant share of production in the country is de facto already working for foreign economic agents through the withdrawal of capital to offshore harbors. Therefore, in order to fully talk about defending national interests and, perhaps, even the workers who produce these same goods and services, it is necessary to first create conditions for sustainable development within the country.

The general reasons for the aggravation of the economic crisis in Ukraine in recent years are the massive withdrawal of capital as a result of political instability and further devaluation of the national currency; and the growing dependence (amid falling domestic demand) on the global market for raw materials which Ukrainian enterprises specialize in supplying in the global division of labor. Such trends could not but affect qualitative changes in the structure of the economy.

Structural changes in the economy

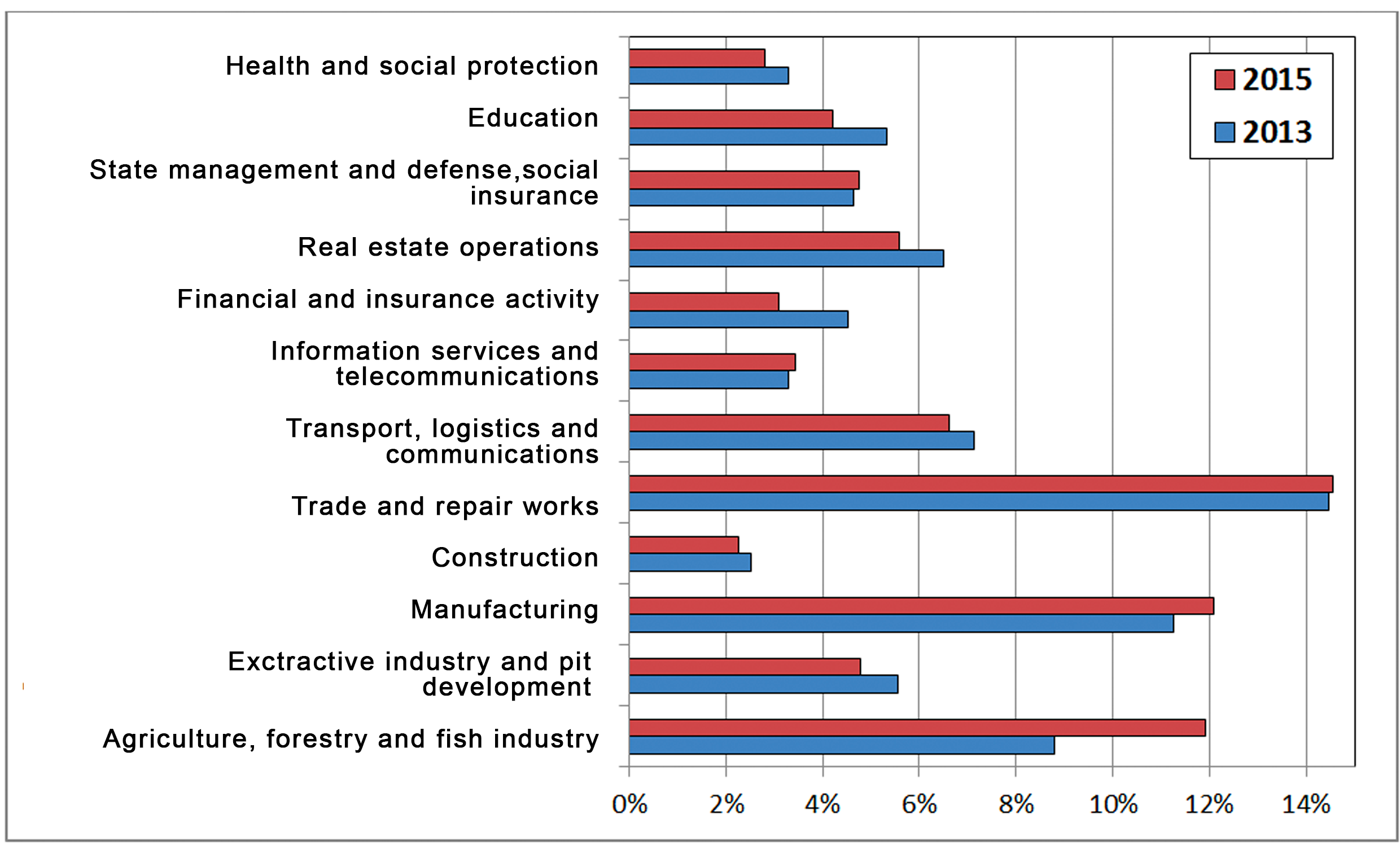

Between 2014 and 2015, Ukraine's real GDP (adjusted for inflation) declined by 15.9%. However, this decline was accompanied by an uneven deterioration in different sectors of the country's economy. Numerous external and internal factors caused significant changes at the level of entire industries. Let's compare their share in the economy in 2013 and 2015 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Structural changes in the economy of Ukraine in 2014-2015[2], share of GDP [according to the data of the State statistics service of Ukraine]

As we can see from the figure, the role of the agricultural sector has increased since 2013 – its share in GDP reached 11.9% in 2015 (8.8% in 2013). In 2015, agricultural enterprises had produce worth UAH 544 billion [NBU]. At the same time, we should not forget that agrarians, producing competitive products due to the cheapness of Ukrainian resources, continue to pay minimum taxes to the budget [Kravchuk, Odosiy, 2015].

Furthermore, the growth of agriculture and forestry was not due to the expected accelerated development of these sectors and the transformation of Ukraine into an advanced agricultural country, but rather to the fact that the decline in these sectors was somewhat lower than the average for the economy, as well as to the faster growth of selling prices. This is confirmed by production data. For example, gross output of livestock products in physical terms decreased by 4% over two years, and crop production by 2.2%. The decline continues in 2016. The largest decline was in egg production (-15%, to 16.8 million eggs per year), which was caused by the almost complete closure of export channels for this type of product to the Russian Federation and the saturation of the domestic market.

The role of the extractive industry in the economy is still declining (to 4.8%), despite the expectations of international capital investment in this area. One of the reasons for this phenomenon is the futility of the policy of reorienting the industry to ever lower levels of technological processing (selling ore instead of steel) with increasing pressure on Ukrainian producers from competitors who introduce new and more effective production facilities [Prokhorenko, Kravchuk, 2015].

The financial sector crisis and the slowdown in lending resulted in a significant contraction of the financial services market (3.1% of GDP in 2015). According to the National Bank's official reports, between January 2014 and April 2016, the total amount of outstanding loans to individuals decreased by 13% to UAH 145.7 billion. Interestingly, over the same period, overdue loans tripled to 23% of all loans [NBU]. This indicates a decline in the solvency of Ukrainian citizens, which threatens to lead to an even greater crisis of non-payment on loans issued in previous, relatively "full" years.

Changes in the banking sector should be mentioned separately. Over the past two years, the new NBU leadership has been actively cleaning up the financial system, which was one of the conditions for international financial institutions to lend to Ukraine. Among other things, this has led to an increase in the influence of foreign banks. Thus, since the beginning of 2014, the share of foreign investors in the authorized capital of banks has increased by more than a third to 45.9%. Of the 180 banks operating in 2014, 109 remained by May 2016, of which 42 were banks with foreign capital [НБУ]. At this price, a certain stabilization of the banking sector was indeed achieved, but at the same time, Ukraine's dependence on foreign financial institutions increased.

But the most significant change in the country's financial system was Ukraine's transition (at the suggestion of the International Monetary Fund) to an inflation targeting policy. This policy defines inflation control as the main goal of the national bank, although the Constitution of Ukraine (Article 99) states that the main function of the National Bank is to "ensure the stability of the currency" and the Law on the National Bank (Article 6) mentions "promoting sustainable economic growth" among the main functions of this regulator.

The NBU will achieve the inflation target under the inflation targeting regime (12% according to the 2016 plan) primarily by regulating the key policy rate (the interest rate at which the NBU lends money to commercial banks, which directly affects the cost of loans for legal entities and individuals) [Memorandum of the NBU with the IMF on Financial Sector Policy, Roadmap of the National Bank of Ukraine for the Transition to Inflation Targeting]. Now, in the context of a certain economic stabilization compared to previous years, the NBU is gradually reducing the key policy rate, which, however, is still at a record level over the past 15 years.

As of June 16, 2016, the key policy rate was 18%, compared to 7% at the end of 2013. As a result, we are witnessing a rise in the cost of loans in Ukraine – up to 30% per annum for individuals, as well as an absolute decrease in lending. This reduces effective demand within the country and slows down potential economic growth. While in 2013, individuals were granted loans worth UAH 90.7 billion, in 2014 it was UAH 61.9 billion, and in 2015 it was UAH 40.4 billion. Lending to the corporate sector is declining at a slower pace [Interest rates on loans and deposits, NBU].

In our view, Ukraine’s unquestioning transition to an inflation targeting policy is a threat to economic development. After all, inflation control as the main goal for national banks, which is now being imposed on developing countries, does not take into account another task that such institutions should be promoting – economic growth. "For some reason" in the United States, the national financial regulator is responsible not only for price stability, as is required of other countries, but also for unemployment (and thus indirectly for economic growth).

In general, transition to such a policy is appropriate if a number of factors are present: current inflation is less than 10%, the economy is not dependent on price fluctuations in foreign markets, and the financial system is stable [Ryazanov, 2014]. However, these conditions are not currently met by Ukraine's economy. Moreover, the crisis of recent years, even in developed countries, shows that inflation targeting, even with unprecedentedly low rates in the developed economies of the EU (0.05%) and the United States (0.5%), is not able to ensure the restoration of stable economic growth. In the Ukrainian context, restraining lending and consumer demand while simultaneously deregulating and limiting the instruments of government influence on economic growth will mean actually freezing stagnation and preserving the inefficient structure of the economy. This raises questions about the true goals of such a policy and who benefits from it. The beneficiaries of this situation may be those state-corporate structures that currently play leading roles in the international arena and are not interested in the economic rise of another player in the Eastern European region.

Accordingly, as real estate lending declines, the share of this industry in GDP is also falling (to 5.6%). However, it should be noted that in physical terms, the construction sector is even showing growth. In 2015, the largest number of residential properties commissioned in the last ten years was recorded (with a total area of over 11 million m2). Not least, this dynamic is ensured by the completion of construction projects of previous years. However, it should be understood that "commissioning" does not mean "sale and occupancy". Therefore, given the reduction in bank lending, the increase in housing supply is likely to continue to put pressure on housing prices in Ukraine, causing them to fall.

The volume of transportation services also declined. This is due, on the one hand, to the loss of traffic flows in the eastern regions (the volume of rail freight transportation in Ukraine as a whole decreased by 17% over two years), and, on the other hand, to a reduction in transit traffic through Ukraine and a drop in the volume of goods shipped for export.

We see a projected reduction in funding for education and healthcare, caused not least by a reduction in social services commissioning and, accordingly, funding for other sectors through the state budget of Ukraine.

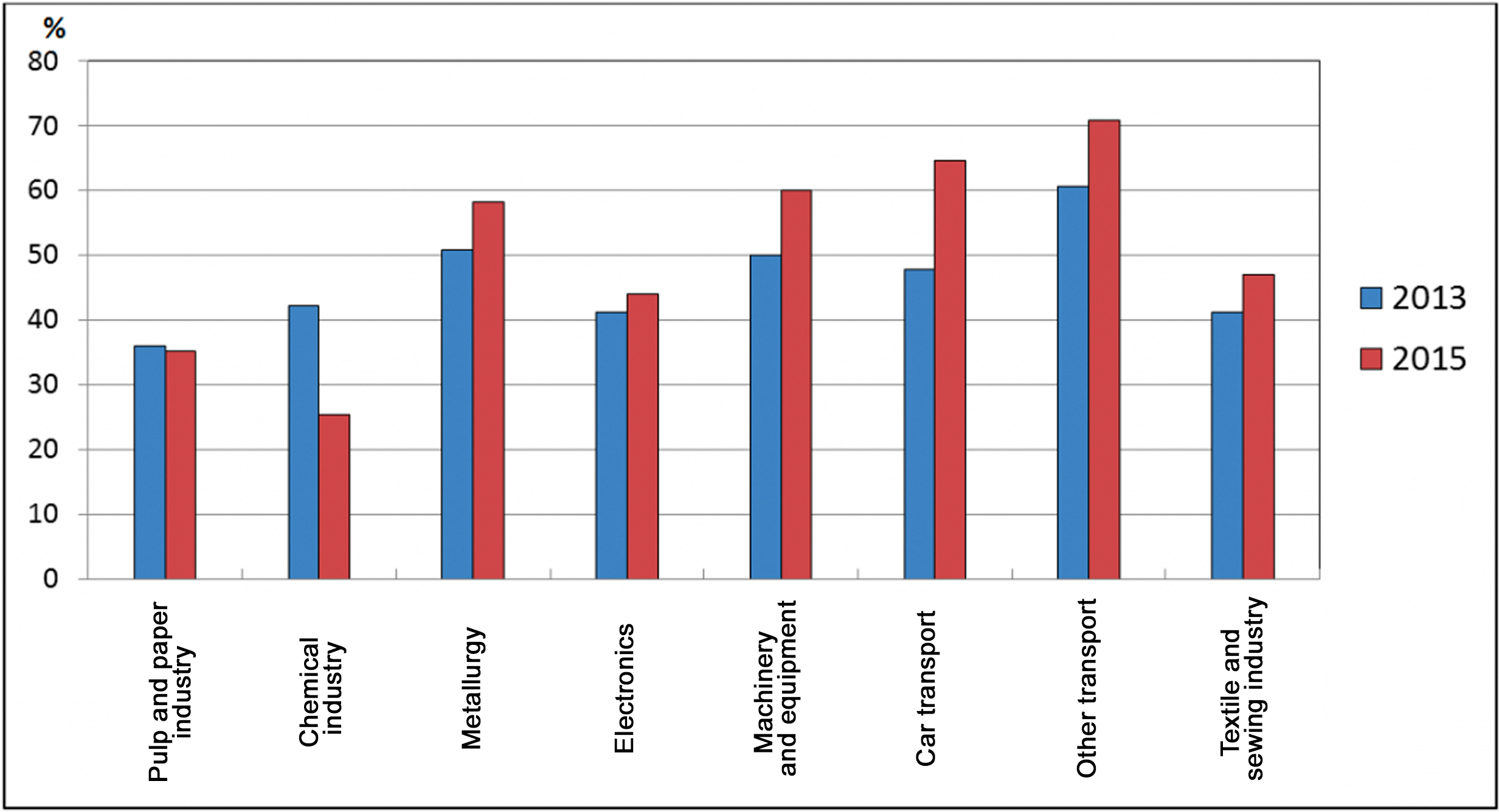

Some growth in the share of the manufacturing industry in the economy in monetary terms is positive, as it is characterized by a generally higher technological level and degree of processing of raw materials. However, we should remember that such changes are driven by rising product prices and are often accompanied by a physical reduction in production. To understand the extent to which manufacturing products are covered by domestic demand, let's analyze the role of foreign orders for industrial products separately (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Share of foreign orders for production of certain types of manufacturing in 2013 and 2015 [according to the State Statistics Service of Ukraine]

As can be seen from the figure, over the past two years, the overall focus on foreign markets has only increased. On the one hand, Ukrainian producers are more interested in working with foreign buyers, but on the other hand, this indicates a decline in domestic demand for Ukrainian products. In particular, the share of foreign orders from metallurgical enterprises increased from 50.9% to 58.2% (in absolute terms, this is UAH 129 billion, or 60% of all new orders in the manufacturing industry). And this is happening at a time when Ukraine has accumulated a huge number of problems with the state of its water supply and sewerage networks.

Similar trends of reorientation to foreign markets are taking place in all other manufacturing industries, except for the pulp and paper industry and, especially, the chemical industry (the share of foreign orders decreased from 42.2% to 25.4%). In 2012, Ukrainian chemical companies sold over USD 6 billion worth of products abroad. (third place in the country in terms of exports after metallurgists and agrarians), in 2013 it was already 4.3 billion, in 2014 – 3.7 billion, and in 2015 – only 1.3 billion dollars.

The chemical industry is a good example of the consequences of the dependence of the commodity sectors of the economy on foreign markets. For example, in recent years, Ukrainian producers of ammonia and urea (the main chemical exports) have been pushed out of business everywhere. In the United States, they have been replaced by new producers after the shale gas boom. Since 2013, the massive entry of Chinese producers with cheap products into the global market has become another factor of increased competition. Given the high cost of gas as the main cost component for Ukrainian producers, their prospects on the global stage remain unoptimistic. The internal situation in the industry is also negatively affected by the struggle of oligarchic capital for the remaining resource base in the country. Most large chemical enterprises belong to the financial and industrial group of Dmytro Firtash, whose property is being redistributed by new groups that now determine the country's economic course. The failure to resolve the conflict in eastern Ukraine also prevents chemical producers from entering European markets with high quality products manufactured at the high-tech Stirol plant in Horlivka (which is currently not under the control of the Ukrainian government), as the company has not yet resumed operations. However, some compensation for the losses in foreign markets can be seen in the reorientation of chemical producers to the Ukrainian consumer of fertilizers, and this is supported by the growth of agriculture [Voskresenska E., 2015].

A similar situation threatens other industries that produce products with a low level of processing, in particular metallurgists, who are also losing out in the competition for consumers.

Thus, if the current policy of non-interference in the economy is maintained, and there are no effective programs of scientific and technological development in the remaining knowledge-intensive industries, the economic structure will continue to degrade and Ukrainian industry will become more dependent on foreign markets. Furthermore, Ukrainian producers are unlikely to maintain their competitive advantages due to the rapid reduction in labor costs. After all, even this "trump card" will be overlapped by the introduction of energy-efficient and automated production in the world's leading economies. Therefore, if Ukraine stays the same course, it will continue to move toward the level of the least developed countries with a corresponding deterioration in socioeconomic conditions for the population. It is necessary to restore the lost independence in financial and economic policy, which should be focused not on satisfying the interests of foreign financial institutions, but on ensuring sustainable innovative development and meeting the needs of the majority.

Next part of the economic analysis offers the assessment of changes in foreign economic activity as a result of the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the European Union.

References [in Ukrainian]:

World Bank Open Data. Indicators [Електронний ресурс] // The World Bank.

Воскресенская Е. Экономика после Майдана. Химики переориентируются на внутренний рынок [Електронний ресурс] / Елена Воскресенская // Экономическая правда. – 2015.

Дорожня карта Національного банку України з переходу до інфляційного таргетування [Електронний ресурс] / Національний Банк України. – 2016.

Економіка України показала зростання у першому кварталі [Електронний ресурс] // Економічна правда. – 2016.

Закон України “Про Національний банк України” // Відомості Верховної Ради України (ВВР). – 1999. № 29. – С. 238.

Конституція України // (Відомості Верховної Ради України (ВВР). – 1996. – № 30. – С. 141.

Кравчук О. В. Оподаткування в Україні. Приховані ресурси [Електронний ресурс] / О. В. Кравчук, О. В. Одосій // Журнал соціальної критики «Спільне». – 2015.

Кравчук О. В. Україна офшорна. Історія формування вітчизняної моделі економіки [Електронний ресурс] / О. В. Кравчук // Журнал соціальної критики «Спільне». – 2015.

Меморандум з МВФ щодо політики у фінансовому секторі від 05 серпня 2015 року [Електронний ресурс] / Національний Банк України. – 2015.

Офіційна інтернет-сторінка Державної служби статистики України [Електронний ресурс].

Офіційна інтернет-сторінка Державної казначейської служби України [Електронний ресурс].

Офіційна інтернет-сторінка Національного банку України [Електронний ресурс].

Прохоренко О. С. Сировинні ресурси – сировинна країна? (до ситуації в гірничо-металургійному комплексі України) [електронний ресурс] / О. С. Прохоренко, О. В. Кравчук // Журнал соціальної критики «Спільне». – 2016.

Рязанов В. Т. Экономическая политика после кризиса: станет ли она снова кейнсианской? / В. Т. Рязанов. // Экономика Украины. – 2014. – № 5. – С. 4–27.

Footnotes

- ^ The indicator was chosen as it allows comparing the scale of economies and assessing the overall economic development of the country. For comparison, data for full reporting years will be taken into account.

- ^ Data for 2013 and 2015 do not include annexed territories of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol.

Author: Oleksandr Kravchuk

Translation: Anastasiya Ryabchuk