On the eve of September 1st, the Day of Knowledge, Commons spoke to activists of the student union Priama Diia about the right to education in a country at war. They explain why they decided to relaunch the union, what obstacles there are to protecting students' rights, and share their plans and dreams for the future of Ukrainian education after the war.

The Commons editorial board: The union's history goes back almost 30 years. Many of our editors and contributors were Priama Diia members during their studenthood. However, in the mid-2010s, the union declined. How did you come up with the idea of reviving it?

The Priama Diia: The rebirth of the union began with a wave of dissatisfaction with the forthcoming reform. In 2021, the Ukrainian Ministry of Education and Science launched a new reform to optimise higher education establishments: universities that were “unprofitable for the state” would be integrated into more efficient universities. This meant losing the material base of these educational establishments, mass redundancies of teaching staff and the abolition of state scholarships for students. Of the 150 largest state universities, 80 were to remain.

The reform outraged students and teachers, which led to demonstrations in various Ukrainian cities. The most significant action occurred on 2 December 2021, when students and everyone concerned opposed the merger of the Kharkiv National University of Construction and Architecture with the Beketov National University of Oil and Gas. Soon-to-be Priama Diia activists also helped to prepare the demonstration. The lack of a powerful trade union and organisational experience was a major obstacle at the time, as the students needed to consider the universality of their problem, had no experience of fighting for their rights regularly and had a vague vision of their objectives. Organisations affiliated with the administration did not want to participate in protest activities, and independent student associations remained silent or supported the neoliberal mantras about the need to privatise education and the whole social sphere in Ukraine.

Protest against the closing of the KhNUBA, Kharkiv, December 2, 2021. Photo: Tymofiy Klubenko

Legal, economic and educational problems were piling up exponentially. Only the left had a critical vision and an understanding of a valid alternative, but there was no left-wing youth organisation in Ukraine then. We knew the Priama Diia union had existed, and we spoke to its former members, who are still influential activists. Their successes and efforts inspired us to recreate the movement. A few months after the autumn demonstrations, the full-scale invasion began. The number of challenges for us increased dramatically. Since then, we have been actively involved in volunteering, helping students at a local level and joining in student actions close to home.

Evacuation, destruction of housing, eviction from dormitories, loss of contact with parents, loss of jobs and a general lack of stability… In these challenging circumstances, the students also came up against total incomprehension by the university administrations.

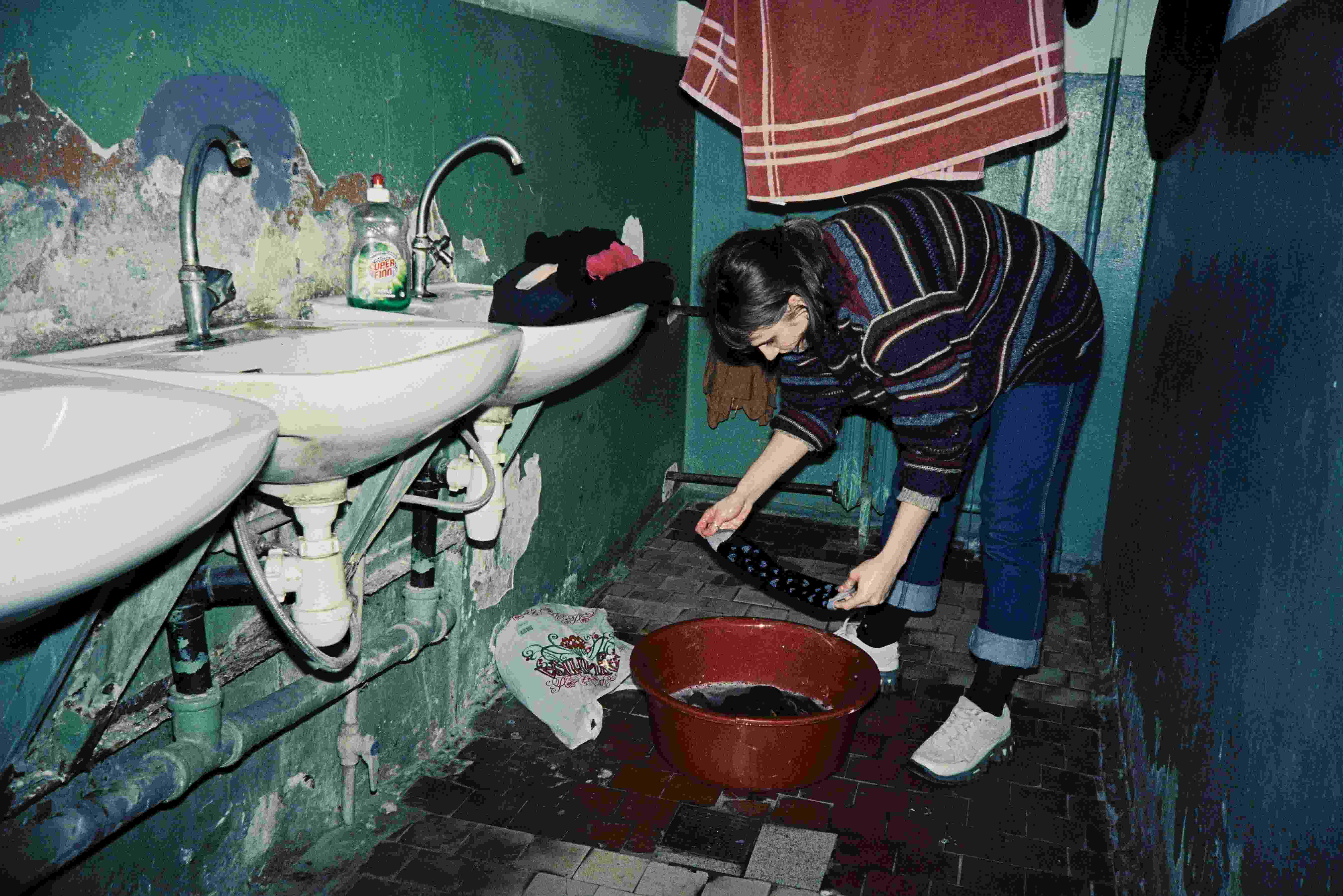

The education system, eroded by years of state irresponsibility, began to writhe in pain. Maintaining a necessary level of learning became almost impossible, as students were in danger every day and, in some parts of Ukraine, directly threatened with death. Evacuation, destruction of housing, eviction from dormitories, loss of contact with parents, loss of jobs and a general lack of stability… In these challenging circumstances, the students also came up against total incomprehension by the university administrations. The level of abuse increased significantly. Many of us felt these problems acutely.

Students in an improvised shelter in the basement of a dormitory, Kharkiv, 2022. Photo: Lev Turkov

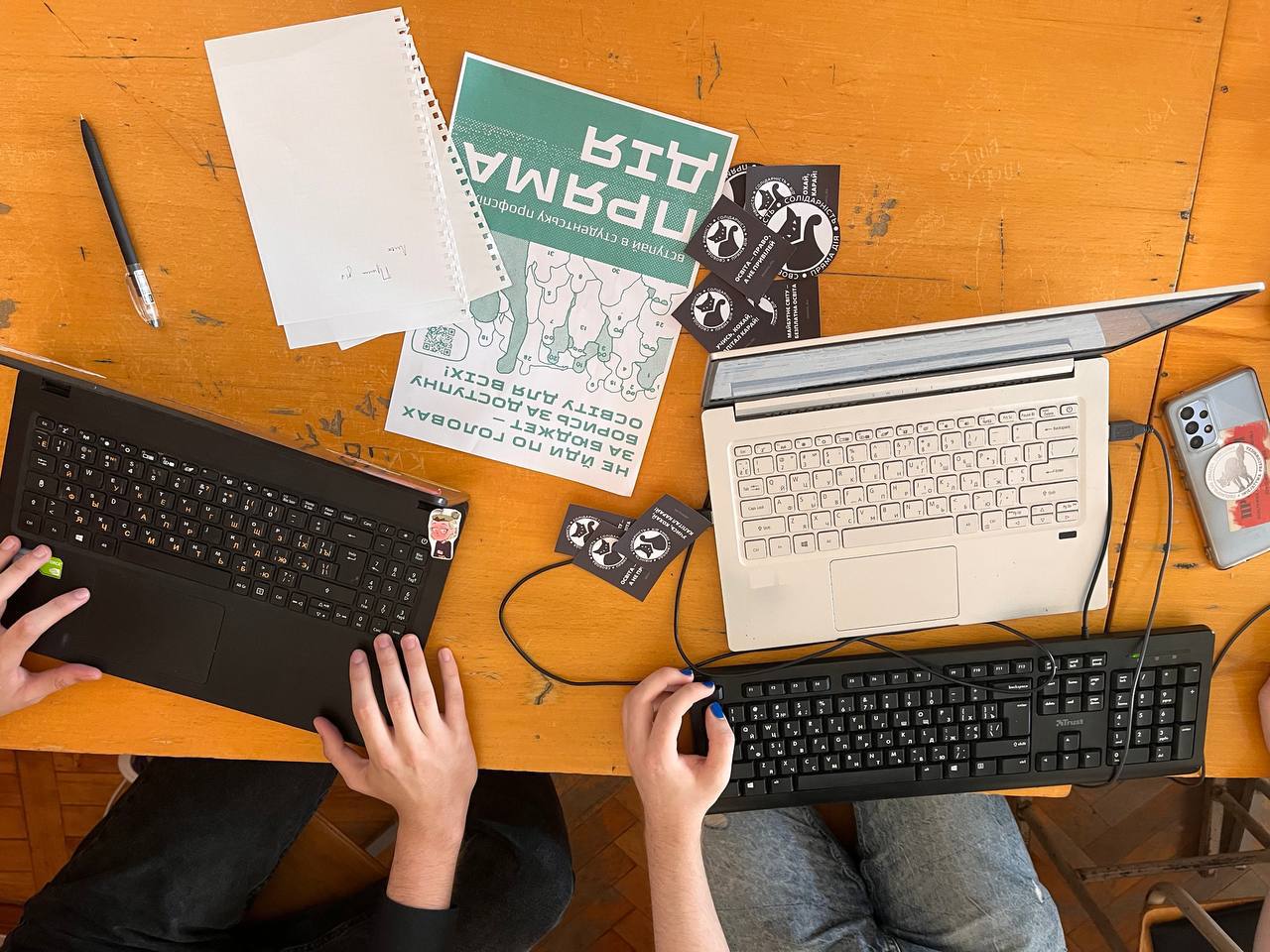

Finally, we analysed the new conditions, pulled ourselves together and realised there was no point in waiting any longer. In February 2023, we, a group of 3 to 5 left-wing activists, launched an open call to students wishing to join the Priama Diia. The result was unexpected, as our organisation started growing fast: the lack of access to offline education and the small number of genuinely left-wing organisations in Ukraine played their part — young people were hungry for activism.

For many, forming a new Ukrainian identity is negative: “We are not-Russia”.

The Priama Diia in previous generations was an anarcho-syndicalist union. What are your political positions today? How does the current generation of students view left-wing politics?

We are noticing the following trend: since the start of the large-scale invasion, many people, including youth and students, have felt the need to get involved in the social, public and political life of the country. This can be explained in various ways, for example, by the fact that everyone is trying to find their place in the resistance to Russian imperialism, whether through volunteering, organising various training courses or joining the Armed resistance.

Of course, for many, forming a new Ukrainian identity is negative: “We are not-Russia”. Whether this is a productive strategy for building a community is another matter. However, it is clear that young people primarily form their worldview by contrasting Russian authoritarianism with democracy, persecution of the gay community with inclusion, and so on. As a result, we are seeing a rise in culturally leftist views among students: these people generally describe themselves as liberals, in the American sense.

Protest by students of the Ukrainian Academy of Printing, Lviv, November 12, 2022. Photo: Priama Diia's archive

That is why we are working mainly with this segment of the public. There is no doubt that Priama Diia today continues to demonstrate the need to combine political and trade union visions in order to organise a powerful student movement. The issues we raise would be superficial if we did not emphasise that our strategic demands are, first and foremost, political. For example, affordable or even free education is a demand for this specific sector, education, but only through an in-depth transformation of the social and political system will such demands take on their whole meaning.

The Priama Diia is today a left-wing student union in the broadest sense.

From this point of view, the union comprises two poles which, in our opinion, are not viable without each other: the vast student community, which is directly linked to the experience of the educational process, its shortcomings and deficiencies, and the militant core, which brings a radical political programme and universalises specific problems. This means that to join Priama Diia, one does not need to be reading volumes of Proudhon or Marx; one just needs to agree with the minimum requirements, i.e. the inadmissibility of discrimination on several grounds — gender identity, race, etc. — and to be wishing to take action. The militant backbone now includes anarchists, Marxists, social democrats and supporters of more exotic currents of political thought. In short, the Priama Diia is today a left-wing student union in the broadest sense.

What political organisations and trends do you follow, both historically and today? Who are your allies in Ukraine and abroad?

On the one hand, we try to experiment with the structure to invent new forms and principles of organisation. This form of political creativity requires a great deal of internal flexibility. For example, to involve the less active participants and coordinate our work, we created the Coordination Headquarters, whose members are elected by sortition (according to the traditions of Antiquity). When we encountered problems in the operation of this body, we would meet to analyse the reasons for them, think about how to overcome the shortcomings, and so on. Today, to a large extent, the Coordination Headquarters works the way we wanted and shows that such “bizarre” and ultra-democratic forms can work — you just have to experiment with and improve them along the way.

PD activists near the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, May 1, 2023. Photo: Priama Diia's archive

On the other hand, when we do not need to reinvent the wheel, we turn to historical experience. The student movement has a long history in different chronological and geographical contexts. By studying this heritage and being aware of the differences with the current situation, we can avoid repeating the same mistakes.

This is how we began to study the student union movement in Quebec, a region where it is still strong today. Since 1968, the province has had a distinctive student association structure that ensures the re-enactment of teaching strikes and general assemblies of teachers and students. We drew inspiration from ASSÉ (the Association pour la solidarité syndicale étudiante), which existed from 2001 to 2019 and had 34 member associations with 56,000 students while remaining left-wing. We continue to study their strategies, tactics and internal organisation, looking for things that can be adapted and work in our context. For example, the concept of 'students as workers' allows us to address several issues in higher education in a different way, creating a space for solidarity not only with other student groups and movements but also with other trade union initiatives: nursing, construction, and those launched by service workers (where students often work part-time because of low stipends).

It is worth noting that we have friendly contacts with the Polish organisation “Koło Młodych”, part of the trade union “Inicjatywa Pracownicza”, where our activists recently attended a conference, shared their experience and helped organise training. We also have close links with the French student organisation “Solidaires-étudiantes”.

“Koło Młodych” congress attended by PD activists, August 2023. Photo: Priama Diia's archive

In Ukraine, the situation is somewhat different. Most Ukrainian student initiatives, such as the Ukrainian Students for Freedom or the Ukrainian Students League, have fundamentally different principles to ours. The USF is a right-wing libertarian organisation focusing mainly on political issues, leaving social issues aside. Sometimes, their ideological underpinnings produce, in our view, openly anti-student positions: during the reorganisation of the Kharkiv NUBA, in the course of which some members of staff had to lose their jobs and students had to lose their state-funded places, USF refused to cooperate during the protest because it considered this “optimisation” expedient.

Nevertheless, we are happy to cooperate with student councils, organisations and other forms of autonomy that operate within universities. Their actions are admittedly limited, as the university administration governs them, but joint projects and communication are an important part of our work. We need activists through student associations at various universities to find out about problems, corruption and so on. Sometimes, these student associations are not happy to cooperate with us because they find us suspicious, but in general, we often manage to establish communication.

Your generation of activists has the most difficult tasks. What issues does Priama Diia deal with? What are your main activities today?

One can divide our tasks into two categories: those related to the state's education policy during the war and those of a more general nature, such as promoting emancipatory tendencies in the organisation of education, the fight against discrimination, eco-activism, and the popularisation of left-wing ideas among young people.

Allowing male students to study abroad is one of the main demands of our union.

We all know that during martial law, men of military age are not allowed to leave the country. This ban applies to students, whether they are studying abroad or in Ukraine. This state policy considerably hampers the educational process, as students enrolled in foreign educational establishments need to travel to their place of study. In an environment where local universities are systematically underfunded and the level of teaching declines due to overwork, students lose motivation and do not receive all the knowledge they need. As a result, shortly, we will face a shortage of the professionals needed to support Ukraine's society and economy and, hopefully, a successful post-war reconstruction. This is why allowing male students to study abroad is one of the main demands of our union.

Photo: Priama Diia's archive

In May 2023, we launched the StudAk campaign to fight for the right to take a gap year and enjoy social guarantees provided by the pre-war legislation. University administrations promised students that, after a legal break, they could return to free education, which they had been waiting for. However, in the autumn of 2022, the Department of Education and Science issued Resolution No. 1224, which effectively abolished all state scholarships for these students.

As the first step, we contacted the victims to assess the scale of the problem. To this end, we have sent hundreds of letters to the student councils and rectors of the country's various universities. However, we have not received a significant response (around five replies). We have also contacted foundations to ask them to cover the costs of particularly hard-hit students. In any case, we have not found any support from universities or government agencies. We are now at a crossroads: some see direct action as the last chance to make our voices heard, while others consider contacting the media.

A few days ago, we launched a petition to transform the former Russian embassy building in Kyiv into a community centre. Instead of staying empty or being turned into another shopping centre, this space will become a meeting point where students can share their knowledge and experiences. This will make it easier to generate new ideas and work together to implement them. In addition, the community centre will support people who need help and shelter. If the petition does not receive a large-scale response, we plan to run several rallies to draw attention to the project.

Protest by students of the Ukrainian Academy of Printing, Lviv, November 12, 2022. Photo: Priama Diia's archive

Like many other institutions in Ukrainian society, education requires reform. How do you see a positive future for Ukrainian education? In short, how should a university be organised so that young people want to study there?

Our union has strategic, ambitious and even utopian visions. There are several different positions, and we have yet to formulate a single one, although we hope to draft a manifesto setting out the main principles by the end of the year.

Of course, we agree that education should be affordable, even free. On this basis, the members of the Priama Diia are building different models. Let me give an example. Universities and the higher education system, in general, play an essential role in the reproduction of society: the knowledge at different levels of practical application that students acquire is used in business, industry, management, politics, etc. The material and political benefits we enjoy as a society are deeply rooted in the education system. Consequently, by studying, writing theses and essays and producing ideas, students do part of the work necessary not only for the development of society but also for its reproduction as such. From this point of view, a student acts like a worker, which means they should not only be able to afford their studies — but also get paid for it. The idea of a student wage is not new. At the height of the student movement in the 1970s, it had many supporters and was a concrete demand for the authorities.

Every little victory revives the organisation and takes it to a new level.

To this strategic vision must be added the fundamental autonomy and democratisation of universities. We do not believe that students are “consumers of education”, participants of a market in which knowledge has a utilitarian function. Universities are not supermarkets selling knowledge like biscuits. The knowledge we receive within the higher education system is flexible and is constantly being transformed during the learning process. This is how education improves and adapts to demands.

Therefore, students are full participants in this process and should play an appropriate role in managing it. This is not our whims but a matter of improving higher education, which is increasingly urgent in the context of post-war reconstruction.

Internally displaced student in a dormitory of the Lviv Academy of Arts, 2022. Photo: Oleksiy Chistotin

We need to show the students (including those who left Ukraine) that positive changes are underway in the higher education system. Such transformations are not the fruit of the goodwill of a minister or a president but require a struggle and the involvement of students. Unfortunately, young people today do not see educational problems as exceptional but rather as a regular, “natural” state of affairs. We often hear statements like, “It cannot get any better!” At such times, Mark Fisher's verdict that we have forgotten how to imagine rings true. In order to move things forward, we propose different strategic visions of the ideal education.

Apart from the utopian demands, we acknowledge the challenges that must be dealt with here and now. These trivial problems are the starting point for more critical work: courses lacking syllabi, poorly designed academic calendars, cockroaches in dormitories, and many others. Every little victory revives the organisation and takes it to a new level. For this work “on the ground”, we are now decentralising the organisation and registering branches (union sections) at different universities. It is important not only to focus on the problems of Ukrainian education in general but also to work on a small scale.

What do you wish students on 1st September?

Always to have the power to choose. Choose what you study, who you listen or talk to, and what path you follow. Sometimes, the circumstances leave you little choice and there are thousands of obstacles in your way. That is why we exist as a union, where every student can overcome obstacles and fight for decent education. That is why it is crucial not to succumb to standardisation and “averaging”. Let education give you the means to think critically about the social relations surrounding you, overcome inequality, injustice and arbitrariness, and not drag you into a system built on domination and submission.

Interviewed by Commons

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva

Interview in French: Entre les lignes entre les mots

Interview in Spanish: Viento Sur

Interview in Norwegian: Nyevenstreukraina